As previously mentioned, the terrain of California means that while most of the population may live in coastal cities, those cities tend to have much higher elevations than their Eastern counterparts, high enough to greatly limit the impact of rising sea levels.

There are, however, parts of the state far from the coast.(largely forgotten by the national press but still home to millions of people) that have proven extremely vulnerable to the kind of storms that climate change makes more likely.

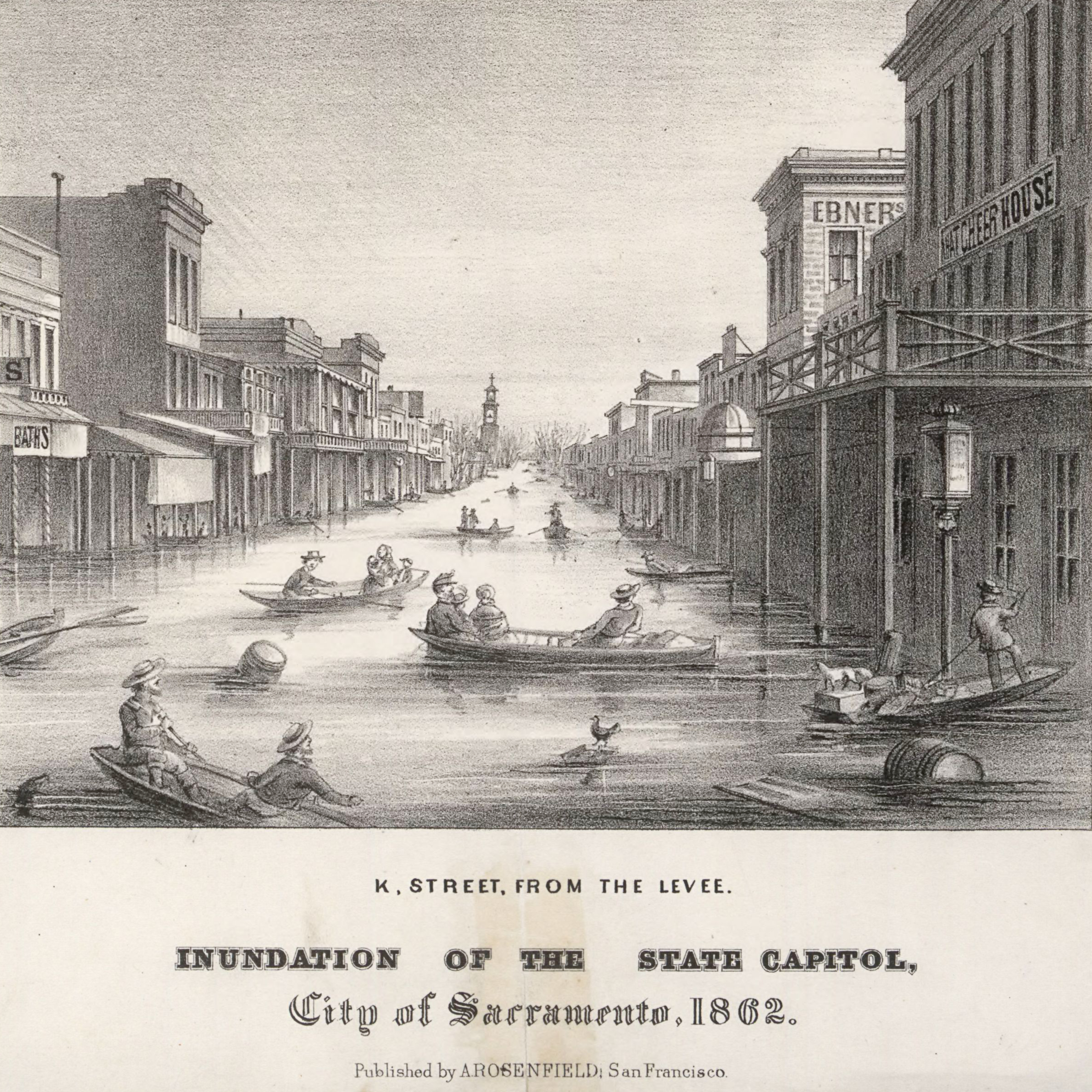

There's a lot of scary history here. [Emphasis added.]

The weather pattern that caused this flood was not from an El Niño-type event, and from the existing Army and private weather records, it has been determined that the polar jet stream was to the north, as the Pacific Northwest experienced a mild rainy pattern for the first half of December 1861. In 2012, hydrologists and meteorologists concluded that the precipitation was likely caused by a series of atmospheric rivers that hit the Western United States along the entire West Coast, from Oregon to Southern California.

An atmospheric river is a wind-borne, deep layer of water vapor with origins in the tropics, extending from the surface to high altitudes, often above 10,000 feet, and concentrated into a relatively narrow band, typically about 400 to 600 kilometres (250 to 370 mi) wide, usually running ahead of a frontal boundary, or merging into it.With the right dynamics in place to provide lift, an atmospheric river can produce astonishing amounts of precipitation, especially if it stalls over an area for any length of time.

The floods followed a 20-year-long drought. During November, prior to the flooding, Oregon had steady but heavier-than-normal rainfall, with heavier snow in the mountains. Researchers believe the jet stream had slipped south, accompanied by freezing conditions reported at Oregon stations by December 25. Heavy rainfall began falling in California as the longwave trough moved south over the state, remaining there until the end of January 1862, causing precipitation to fall everywhere in the state for nearly 40 days. Eventually, the trough moved even further south, causing snow to fall in the Central Valley and surrounding mountain ranges (15 feet of snow in the Sierra Nevada).

...

California was hit by a combination of incessant rain, snow, and then unseasonally high temperatures. In Northern California, it snowed heavily during the later part of November and the first few days of December, when the temperature rose unusually high, until it began to rain. There were four distinct rainy periods: The first occurred on December 9, 1861, the second on December 23–28, the third on January 9–12, and the fourth on January 15–17. Native Americans knew that the Sacramento Valley could become an inland sea when the rains came. Their storytellers described water filling the valley from the Coast Range to the Sierra.

...

The entire Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys were inundated. An area about 300 miles (480 km) long, averaging 20 miles (32 km) in width, and covering 5,000 to 6,000 square miles (13,000 to 16,000 km2) was under water. The water flooding the Central Valley reached depths up to 30 feet (9.1 m), completely submerging telegraph poles that had just been installed between San Francisco and New York. Transportation, mail, and communications across the state were disrupted for a month. Water covered portions of the valley from December 1861, through the spring, and into the summer of 1862.

...

On Inauguration Day, January 10, 1862 the state's eighth governor, Leland Stanford, traveled by rowboat to his inauguration building held at the State Legislature office. Much of Sacramento remained under water for 3 months after the storms passed. As a result of the flooding, from January 23, 1862 the state capital was moved temporarily from Sacramento to San Francisco.

Atmospheric rivers have been coming up in conversation quite a bit this week.

The heavy wind and downpours left tens of thousands of homes in Northern California without power for much of Sunday, while record high waters on the Cosumnes River near Sacramento breached three levees and inundated the area.

Flash flooding along Highway 99 and other roads south of Sacramento submerged dozens of cars near Wilton, where the water poured over the levees. Search and rescue crews in boats and helicopters scrambled to pick up trapped motorists. At least one person was found dead in a submerged car near Dillard Road and Highway 99, according to local media reports.

“I don’t want to use the term apocalyptic, but it’s ugly,” Sacramento County spokesman Matt Robinson said by phone from a stretch of Highway 99 that he described as a vast lake. “We have a lot of stuck cars.”

Downed power lines and trees crashing into homes created further trouble, said Capt. Parker Wilbourn of the Sacramento Metropolitan Fire District.

“It was an extremely busy night,” he said.

Electricity remained cut off midday Sunday for more than 32,000 customers, down from more than 100,000 who lost power overnight around Sacramento. The county warned Sunday afternoon that the floodwaters were rising around Highway 5 near the southern edge of Sacramento’s suburbs.

By late afternoon, as waters rose in the Cosumnes and Mokelumne rivers, authorities issued a mandatory evacuation order for the community of Point Pleasant, south of Elk Grove.

“Please be out of the area and off the roads while there is still light to reasonably see any danger,” Sacramento officials wrote in a message on Twitter. “Take the ‘5 P’s’ with you: People, Pets, Prescriptions, Paperwork and Photos.”

An evacuation center was set up at Wackford Center on Bruceville Road in Elk Grove. “Flooding in the area is imminent,” officials warned. “Floodwaters become incredibly dangerous after sunset.”

Some sunny skies offered much of the state a respite Sunday from the downpours, but another atmospheric river was barreling across the western Pacific and was set to drench California in the days ahead.

No comments:

Post a Comment