* You do realize I just made up the number of days to Halloween, right?

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, December 31, 2021

Thursday, December 30, 2021

Why the right to a lawyer is so important

Imagine this scenario, based on an actual situation:

A business associate calls you and says, "my dear business associate, the shit has hit the fan; Federal Agency X is investigating Project Y we did together. Two Agency X agents are interviewing people.""Oh coitus," says you, or words to that effect, and terminate the conversation.Later that day, two well-dressed and polite agents of Agency X visit you. Because you despise me and want me to weep and gnash my teeth, you consent to be interviewed. At some point, they ask you "have you talked about this investigation with anyone?""No," you say.They smile.At the end of the interview, it occurs to you to ask, "Hey, am I in trouble? Do I need a lawyer?"The agents smirk. "No," they say. "I mean, unless you lied about talking to anyone about this investigation."See, you've fallen into a false statement trap, which I've talked about before. The feds know that you've talked to somebody about their investigation. They were probably standing next to your friend when he made that call this morning. And now you've talked your way into a felony.

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Extrapolating out of range: education edition

I think that if at any time pre-Covid someone had suggested that regular, in-person school attendance was not that important and kids would be okay just watching video lessons and doing online work, that would have been understood as a kind of right-wing techno-libertarian crank viewpoint. Thanks to the pandemic, though, we got to find out if the techno-libertarian cranks are right about school.It turns out that they are not. In Virginia, for example, student test scores plummeted and the racial gap in scores exploded

And we’ve seen this basically everywhere. McKinsey and NWEA found huge learning losses concentrated in poorer kids nationwide. Texas and Indiana reported big early test score declines. A study from the Netherlands indicated that during an eight-week period of virtual schooling, students learned basically nothing on average.

and

For years, study after study has shown that the effect sizes of education interventions tend to be really small. And when they don’t look small, they tend to be very difficult to scale up. That led some people to infer that schooling is largely pointless. But we learned during the pandemic that if you try something out-of-sample like not having school at all, the effects are actually very large.

I think that this example illustrates two major themes.

One, which we've been discussing for ages, is that it is very difficult to extrapolate data out of the range of observation. When there is effective teaching going on then small tweaks with how it is done seem can be challenging to show as having an impact. But let us be frank -- the human species has been educating children in numeracy and literacy for (literally) thousands of years. The Lyceum and the Academy were founded before the dawn of the Roman empire. China has been using exams to evaluate qualified graduates for centuries. Now there can be possibilities to use improved technology and such, but the basic idea is old and small tweaks have been tried for (literally) millennia.

Two, is that disruption is often not focused on the basic delivery of services. Far more common is regulatory evasion. Uber evaded taxi regulations far more than it had a new idea -- taxi companies quickly mimicked the app, the innovation that they had trouble with was the ability of Uber to classify employees as independent contractors. Financial companies often do better by finding ways to evade regulation that protect investors than just finding better investments. [EDIT: In conversations with Mark, he pointed out the precise mechanism by which education disrupters can save money: fewer students with disabilities given the ADA. While this gap is closing, it is still the case that charter schools end up serving fewer students with disabilities than traditional public schools. Insofar as there is any strategy here, this could create a perceived efficiency gap].

It is this second point that always worries me with education reform. There is a lot of money in education, finding a way to skim 1% off of the top would be worth billions per year. When real progress is hard because a system has already been extensively optimized then one should be suspicious of claims of important advances, especially if there is a lot of opportunity for the investment to pay off for the "innovators" involved. Taking away 1% of educational spending and inflating a few numbers might well be a easy pathway to success.

But the first point is well worth remembering -- the system, as is, is already delivering a lot of value and taking it away shows immediate and large effects that reduce outcomes. These are despite the efforts of teachers and parents to continue online.

Or, in other words, one can innovate but always be worried about the arguments that a system centuries in the making is fundamentally flawed. It might be for some areas (e.g., computer programming is relatively new and perhaps autoshop is less related to other crafting skills than I suspect) but this is not a place where the current equilibrium is obviously easy to beat.

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

The biggest problem in California right now is that we don't have enough fires

It's raining as I type this, snowing not that far from here. We've gotten lucky in the past couple of weeks and we are supposed to have another major storm before New Year's Day. All of this means that we desperately need to start planning as soon as possible for teams to go out into the forest and start some fires.

As Elizabeth Weil explains in her Pulitzer-worthy Propublica piece (which we discussed earlier here). [emphasis added]

Yes, there’s been talk across the U.S. Forest Service and California state agencies about doing more prescribed burns [a.k.a. controlled burns -- MP] and managed burns. The point of that “good fire” would be to create a black-and-green checkerboard across the state. The black burned parcels would then provide a series of dampers and dead ends to keep the fire intensity lower when flames spark in hot, dry conditions, as they did this past week. But we’ve had far too little “good fire,” as the Cassandras call it. Too little purposeful, healthy fire. Too few acres intentionally burned or corralled by certified “burn bosses” (yes, that’s the official term in the California Resources Code) to keep communities safe in weeks like this.

Academics believe that between 4.4 million and 11.8 million acres burned each year in prehistoric California. Between 1982 and 1998, California’s agency land managers burned, on average, about 30,000 acres a year. Between 1999 and 2017, that number dropped to an annual 13,000 acres. The state passed a few new laws in 2018 designed to facilitate more intentional burning. But few are optimistic this, alone, will lead to significant change. We live with a deathly backlog. In February 2020, Nature Sustainability published this terrifying conclusion: California would need to burn 20 million acres — an area about the size of Maine — to restabilize in terms of fire.

...

[Deputy fire chief of Yosemite National Park Mike] Beasley earned what he called his “red card,” or wildland firefighter qualification, in 1984. To him, California, today, resembles a rookie pyro Armageddon, its scorched battlefields studded with soldiers wielding fancy tools, executing foolhardy strategy. “Put the wet stuff on the red stuff,” Beasley summed up his assessment of the plan of attack by Cal Fire, the state’s behemoth “emergency response and resource protection” agency. Instead, Beasley believes, fire professionals should be considering ecology and picking their fights: letting fires that pose little risk burn through the stockpiles of fuels. Yet that’s not the mission. “They put fires out, full stop, end of story,” Beasley said of Cal Fire. “They like to keep it clean that way.”

Why is it so difficult to do the smart thing? People get in the way. From Marketplace.

Molly Wood: You spoke with all these experts who have been advocating for good fire for prescribed burns for decades. And nobody disagrees, right? You found that there is no scientific disagreement that this is the way to prevent megafires. So how come it never happens?

Elizabeth Weil: You know, that’s a really good question. I talked to a lot of scientists who have been talking about this, as you said, literally, for decades, and it’s been really painful to watch the West burn. It hasn’t been happening because people don’t like smoke. It hasn’t been happening, because of very well-intended environmental regulations like the Clean Air Act that make it harder to put particulate matter in the air from man-made causes. It hasn’t happened because of where we live. You don’t want to burn down people’s houses, obviously.

The term "controlled burn" is always at least slightly aspirational, and as the Western fire season gets longer and longer, our window for safe prescribed burns gets shorter and shorter. As a result, this may be the most urgent environmental action places like California need to take. If the weather takes a bad turn, a delay of two or three weeks can mean missing an opportunity to mitigate disaster in the Summer and Fall.

We've missed too many already.

Monday, December 27, 2021

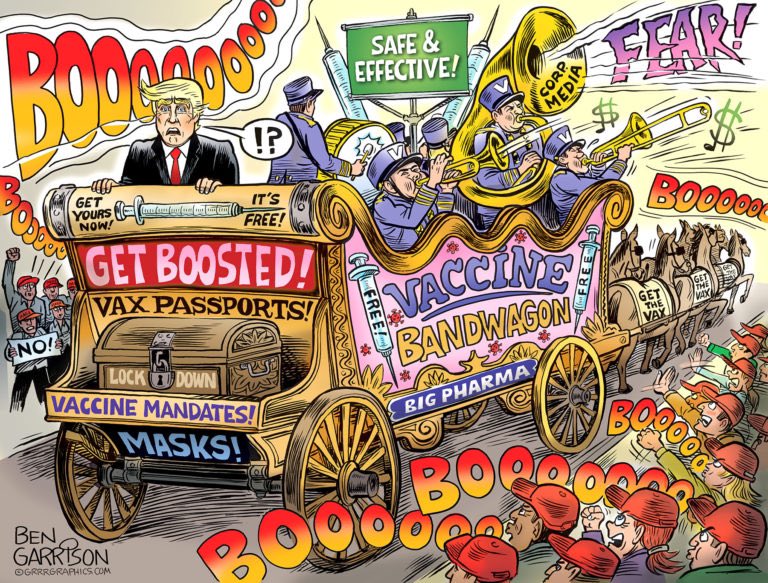

Against feral disinformation, the very liars themselves contend in vain.

Without feral disinformation and the cultivation of the lunatic fringe, we never would have had a Trump nomination. The Republican establishment was forced to accept a candidate whom they felt was extremely dangerous to the future of the party because the conservative movement had lost control of the narrative they created; it took on a life of its own.

Initially, Trump spread more more disinformation -- downplaying the severity and promoting worthless cures -- because that approach appeared to help him politically. Now, it is in his advantage to take credit for the vaccines and their impact, but the narrative kept evolving until even he isn't allowed to correct the lies he told.

“The ones who get very sick and go to the hospital are the ones that don’t take the vaccine. … if you do get it, it’s a very minor form. .. People aren’t dying when they take the vaccine.” -Donald Trumphttps://t.co/DobGKouFKo

— Edward-Isaac Dovere (@IsaacDovere) December 23, 2021

Candace Owens is doing damage control after “so many donors and supporters” are upset over Trump’s vaccine comments. She says he is old, isn’t tech savvy, doesn’t keep up with or read obscure internet conspiracies, and only follows the main stream media so doesn’t have the facts. pic.twitter.com/XAuTFfellE

— Ron Filipkowski (@RonFilipkowski) December 24, 2021

Alex Jones: “This is an emergency Christmas Day warning to Pres Trump. You are either completely ignorant .. or you are one of the most evil men who ever lived .. What you told Candace Owens is nothing but a raft of dirty lies.” pic.twitter.com/rNCNdvgNrm

— Ron Filipkowski (@RonFilipkowski) December 25, 2021

FRIDAY, JULY 23, 2021

Feral Disinformation

Another one for the lexicon.

Disinformation has gone feral when:

1. It is no longer in the control of the group that created it.

2. It has continued to grow in popularity and influence.

3. It has started to evolve in such a way that the nuisance/threat it presents is as as great to the people who created it as it does to the original targets.

The most prominent example of the moment is the right wing movement opposing covid vaccines and increasingly vaccination in general.

The Conservative Movement spent decades depicting the scientific establishment as alarmist and corrupt because undermining it served a clear political purpose at the time. Recently this narrative took on an added usefulness as the Republicans tried to contain the fallout from the pandemic. It was an unspeakably evil position to take, greatly adding to a horrific death toll, but it had a certain ends-justify-the-means logic, "had" being the operative word.

In 2021, being the anti-vax party is not in the Republicans' best interest. It devastates areas that voted for Trump and it makes the most comically crazy people imaginable the face of the GOP. On top of that, it's bad for business.

The best messaging for the Republicans at this point would be to start referring to the "Trump vaccines" and to work the phrase "Operation Warp Speed" into every statement and interview response, regardless of topic, then take credit for the end of the pandemic. That is, however, not an option. Control of the narrative has been lost, Things have gone feral.Over the past the past week, the GOP establishment made a coordinated effort to move away from this disastrous message.

The pivot is not going well.

Saturday, December 25, 2021

Friday, December 24, 2021

Thursday, December 23, 2021

Perfect last-minute gift idea

From FTExcited for this new venture, which combines my passion for art and commitment to helping our Nation’s children fulfill their own unique American Dream. #MelaniaNFT https://t.co/XJN18tMllg pic.twitter.com/wMpmDDsQdp

— MELANIA TRUMP (@MELANIATRUMP) December 16, 2021

That’s right. Generous billionaire’s wife Melania is giving an (unspecified) portion of the proceeds from the sale of her “new NFT endeavor” to assisting “children in the foster care community”. Who said philanthropy was dead?The NFT, named “Melania’s Vision”, gives the buyer a string of code that supposedly represents “ownership” (this is literally all an NFT is) of “a breathtaking watercolor art” that celebrates Mrs Trump’s cobalt blue eyes. We, not owners of this receipt, have nevertheless copied and pasted the contents of this collectible below for you all (isn’t digital art great like that):

But this is a non-fungible token with a twist. Because it is actually . ... non non-fungible. That’s right, until December 31 you can buy as many of these little wonders, all representing the exact same breath-taking picture, for the microscopic price of 1 Solana (a crypto token), currently worth around $170. She’s practically givin em away!

Wednesday, December 22, 2021

If you've gone through the holidays without hearing "Sugar Rum Cherry"...

... you have not had a cool Christmas.

Tuesday, December 21, 2021

The NYT weighs in again on California housing and it goes even worse than expected

The gray lady has doubled down on the liberal hypocrisy housing narrative with a highly promoted video featuring two of the paper's stars and the results are... not good.

Checkout the 3:40 mark.

Obviously, this graph wasn't telling the story they thought it was telling. My first thought was that we were just seeing the impact of the collapse of the housing bubble which didn't particularly support the NYT's argument, but on closer scrutiny (assuming we can trust the x-axis), I realized it was even worse.

If you take a close look, you'll see that the drop started well before the 2008 collapse.

For the record, I don't know if permits issued is the best metric here -- I'd feel much more comfortable if we had an actual researcher to weigh in -- but the decline is a big part of the NYT's argument so we should probably ask ourselves if anything else of note happened in California around this time...

The Schwarzenegger administration went from 2003 to 2011, or roughly...

The three things which the New York Times loves above all others are putting itself in a position of moral superiority, displaying its "impartiality" by criticizing Democrats, and taking condescending shots at other parts of the country. Add in the paper's well-established preference for talking about rich people and the hypocritical California Democrats narrative is nearly perfect which means we're probably in for still more installments.

Monday, December 20, 2021

An almost complete checklist of the Fall 2021 NIMBY/YIMBY thread

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2021

Yes, YIMBYs can be worse than NIMBYs -- the opening round of the West Coast Stat Views cage match

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2021

Yes, YIMBYs can be worse than NIMBYs Part II -- Peeing in the River

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2021

The cage match goes wild [JAC]

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2021

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2021

Cage match continues on development [JAC]

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2021

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2021

Did the NIMBYs of San Francisco and Santa Monica improve the California housing crisis?

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021

A primer for New Yorkers who want to explain California housing to Californians

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2021

A couple of curious things about Fresno

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2021

Does building where the prices are highest always reduce average commute times?

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2021

Housing costs [JAC]

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 13, 2021

Urbanism [JAC]

MONDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2021

Either this is interesting or I'm doing something wrong

And a study we'll want to come back to:

A spatiotemporal analysis of transit accessibility to low-wage jobs in Miami-Dade County

Friday, December 17, 2021

Food prices

First, there’s a distinct “people on a budget don’t deserve nice chocolate” vibe to many of these comments, which I take umbrage with. Food shaming is pervasive on social media, whether it’s people yucking other people’s yums on a recipe post, commenting on what or how much they are eating, or acting like spending money on a pre-chopped salad kit is tantamount to burning down an orphanage.And while I agree learning to cook is an important life skill and the best form of self-care you can engage in, there are lots of reasons people lean on convenience food — chief among them being convenience, which is right there in the name. Time is our most valuable finite resource, especially in a world that demands a lot of it.

You can see the chocolate below:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)