This is Joseph

Mark has been on a roll with his covid-19 posts of the last two days. One thing that I really want to reinforce is that we have been successful with previous infectious diseases and vaccination. Consider smallpox -- a disease that changed the destiny of nations. It was highly infectious, around for thousands of years, and even in societies that were experience it killed a third of adults. It was eradicated with a combination of vaccines and public health measures.

It is impossible to overstate how bad smallpox was when released in a disease naïve population:

After first contacts with Europeans and Africans, some believe that the death of 90–95% of the native population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases. It is suspected that smallpox was the chief culprit and responsible for killing nearly all of the native inhabitants of the Americas.

Like even if this estimate is too high, the size of the death toll was a complete catastrophe for every population that first encountered it. Consider another random example:

In Japan, the epidemic of 735–737 is believed to have killed as much as one-third of the population

Smallpox outbreaks were huge sources of death and suffering, with high levels of suffering. A vaccination and test/trace campaign ended it as a major source of human mortality and morbidity to the point where it is considered eradicated.

Smallpox is not a unique example. Measles has worse outcomes than covid-19 (one in four hospitalized!), at least in the aggregate and is highly contagious. In fact, both measles and smallpox seem to have a higher reproductive number (R0) than covid-19. This is a little tricky as R0 depends on conditions, and so there is not one single number nor do we really know precisely what the R0 of smallpox would be in modern living conditions. Same with polio, even more famously controlled with a mass vaccination campaign with a four order of magnitude reduction in number of cases.

[Edit: Mark points out that smallpox is one of only two diseases eradicated. Polio and Measles are both still with us but very minor contributors to mortality at the population level. I am very much in favor of eradicating covid-19 -- and measles, and polio, and other dangerous viruses -- but there is a level of control that also mitigates a lot of the impact that can be achieved with vaccination and epidemiologic surveillance]

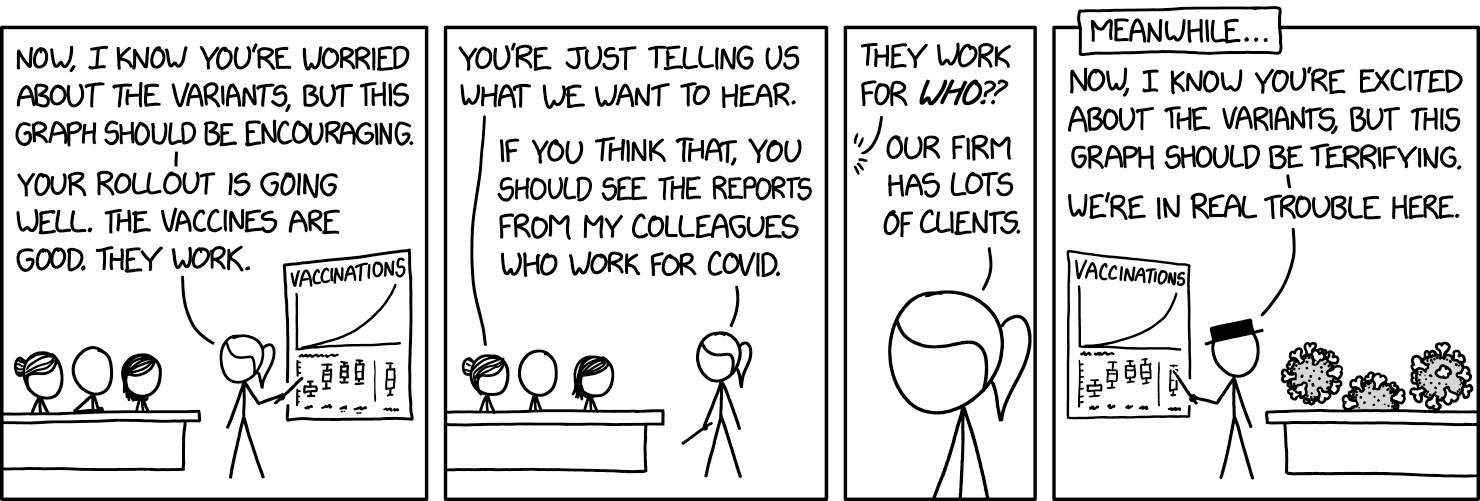

But it is clear that a vaccination campaign is likely to be highly successful. This vaccine science is so nondebatable that I can cite sources like wikipedia for just how effective these campaigns have been at improving public health. It is possible that a concerted campaign of public resistance could undermine the use of vaccines and reduce the benefits. But this is a choice. And it is quite clear that we have the technology to greatly mitigate and reduce the impact of covid-19 on everyday life. It isn't free, but the impacts of the pandemic on the economy are not negligible, either.

Now, it is possible that we might decide that this new social pattern is good for other diseases, like influenza. But, again, this would be a choice. But nobody worries about Polio, Smallpox, or Measles when going to a restaurant, a concert, or a haircut. With determination, there is no evidence that covid-19 cannot be added to this list with a vaccination and public health campaign.