We really should have come back to this one more often. We also should have spent more time reminding everyone what a terrible writer, thinker, and human being Steven Landsburg is.

Not to be confused with Steve Landesberg. That guy was great.

How our inability to distinguish between independence and contrarianism

encourages Steve Landsburg to be, let's just say, a less effective

pundit

[I decided that the tone was getting a bit sharp in this debate so

I'm dialing things down a bit. This entailed some very slight rewriting

but none of these changes the substance of the post]

Before

getting to the main thesis, let's confirm just how bad this incident

was. A radio personality with millions of listeners grossly

misrepresented the comments of a private citizen speaking out on an

issue then used those distortions to make offensive and badly-reasoned

attacks on the the woman. The situation at that point was bad enough

but we don't really achieve horrible until Landsburg jumped in. Not

only did Landsburg throw his reputation behind Limbaugh's illogical and

factually challenged comments, he actually added additional [poor]

arguments to the abuse this woman has had to put up with.

Noah Smith,

Scott Lemieux,

my co-blogger and others have done an excellent job addressing the lies and idiocy of this affair (check out how this blogger

dismembers

the I'm-mocking-the-postion-not-the-person defense) . The question for

now is how this happened. How did a mid-level economist manage to

reach such national prominence by writing a series painfully sophomoric

books and articles?

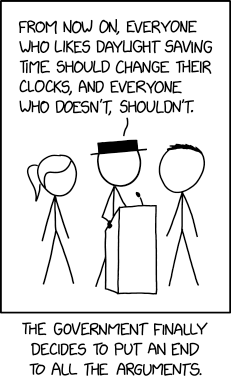

Part of the answer, I'd argue, lies in the

way journalists and editors now treat the counterintuitive.

Publications like Slate give us a steady diet of pieces that take some

claim that seems obviously true and argue the opposite. These

publications would have us believe that this practice is a sign of

intellectual independence and healthy diversity of opinion. It's not.

Contrarianism

is closer to the opposite of independence, a point that's easiest to

explain if we think in the idealized terms of a simplified fitness

landscape. and draw an analogy between the defensibility of an argument

associated with a certain position and the fitness of a phenotype

associated with a certain genotype. (more on

landscapes here)

Of

course, it would take a lot of variables to realistically describe

this landscape but the basic concepts still hold even if we simplify it

to a bare-bones x, y and v(x,y). For every position (x,y) you can

take, there's a resulting viability (v). Some positions are easy to

defend (v is high). Some are difficult (v is low). Pundits and news

analysts who try to find the best positions to argue are therefore

performing an optimization algorithm (though most probably never

thought about it in those terms).

For the most part, we can place this commentary and analyses in three general categories:

Neighborhood

Independent/semi-independent

Contrarian

The

neighbor searcher tries to find the most defensible position within

the neighborhood of a starting point. The best example I can think of

here is the work David Frum specialized in until fairly recently. Frum was

not being independent with his pieces in the Wall Street Journal or

public radio (the terminal point of his searches was almost always

within the neighborhood of the established conservative consensus) but

he was arguably doing something as or more important, thoroughly

exploring the landscape of the region and encouraging evolutionary

shifts to sounder, more defensible positions.

The

independent searcher, by contrast, goes where the search leads

regardless of the starting position. The semi-independent searcher adds

the condition that the terminal point has to be original (in other

words, you can't end up on a point that someone else has already

argued). Technically, originality and independence are in opposition

here but in practice, they tend to complement each other.

And

the two categories tend to complement each other as well. To grossly

oversimplify, one group searches x+1 to x-1 and y+1 to y-1; the other

group searches everywhere else. Given the fact the consensuses

originally form around what seem at the time to be good ideas, it makes

sense to explore their neighborhoods (if it helps, you could think of

this in terms of Bayesian priors), but it also makes sense to keep

exploring new territory. David Brooks and Frank Rich refine and improve

their relative corners of the political landscape while writers like

Jonathan Chait or William Safire range further and are more likely to

reach unexpected conclusions.

The contrarian approach is to start

with a position (x.y) that seems obviously true (often because it is

true) then jump to either (-x,y) or (x,-y) and argue from there. It can,

at first glance, look like the result of an independent search,but it

is actually far more constrained than the neighborhood searches of Frum

and Rich. Both of those writers would shift positions based on their

reasoning and would insist on finding a defensible point before sitting

down to the keyboard.

The typical contrarian piece hews so

closely to its initial (-x,y) that there's no indication of a search at

all. By all appearances, the writer simply jumps to the contrarian

position and starts typing.

Contrarian writing crowds out good

journalism and pumps misinformation and faulty arguments into the

discourse. This would be bad at any time, but in the current state of

journalism, it's disastrous. Here's a list of dangerous trends in

journalism from an earlier

post (with a link added from a different paragraph):

1. Reliable information sources like the CBO are undermined;

2. An increasing amount of our information comes from unreliable subsidized sources like Heritage;

3. Journalists suffer no penalty for publishing inaccurate information;

4. Journalists also fashion for themselves an incredibly self-serving ethical rule

that lets them, in the name of balance, avoid the consequences that

would have to be faced if they honestly assigned responsibility for

screw-ups;

5. A growing tendency to converge on a narrative makes the media easier to manipulate.

All

of these factors make it more difficult for our society to deal with

bad data and contrarians are a rich source of some of the worst.

In

a healthy journalistic system, counter-intuitive claims would be held

to a higher standard (at least if we think like Bayesians) and if a

logically or factually flawed argument made it through, both the authors

and the editors would feel pressure to see that it didn't happen

again.

In our current system, counter-intuitive claims are held

to a lower standard (because they generate traffic) and serial

offenders can actually build careers by badly arguing points that

probably aren't true. Editors have lost all interest in fact-checking

and outside efforts at debunking are usually treated as he said/she

said.

It's easy to object to the positions Landsburg takes, but

perhaps the truly offensive aspect here is the way Landsburg and the

other contrarians reach those positions.