The main highlights seem to be:A lot depends on how you frame the question but if it comes down to a choice between coal and nuclear, I don't have a hard time deciding.

* The accident wasn't the result of a single disaster, but of two, and arguably three: earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent hydrogen explosions.

* The plant survived the earthquake (which exceeded its design requirements) quite well, and the reactors scrammed correctly. However, scrammed reactors continue to need power to run their cooling systems. The earthquake tore down the cables connecting the plant to the rest of the grid, forcing them onto backup power.

* The tsunami struck 15 minutes later, and was roughly five times higher than the plant had been designed for. A review of disaster preparedness in 2002 recommended raising "the average wave height they needed to be designed to cope with to about double the height of the biggest waves in the historical record" — 5.7 metres, for the FD plant. In the event, the tsunami that struck had 15 metre waves. It washed right over the plant and wrecked the seawater intakes, electrical switchgear, backup generators, and on-site diesel storage.

* The 2002 severe accident review that increased the tsunami wave height estimates recommended installing hardened hydrogen release vents, to prevent a build-up of hydrogen in event of a similar accident. These are standard on American and other reactors, but had not been retrofitted to the FD BWRs. Were such vents fitted, the explosions would not have occurred. (The explosions compounded the difficulty of bringing the plant under control.)

* Despite all this there appears to have been no public health impact due to radiation (stress and fear are another matter), and no plant workers were exposed to more than 250 millisieverts — the raised limit for emergency nuclear responders, equal to five years' regular working exposure, but insufficient to cause a serious health risk.

So: serious accident, yes — but it's no Chernobyl. ...The main take-away seems to be that, like a plane crash, it takes more than one thing going wrong to cause an accident — in this case, two major natural disasters, each of which exceeded the plant's design spec, occurring within the space of an hour, compounded by failure to implement a safety system that is standard elsewhere. Despite which, they managed to dodge the bullet (for the most part: it's still going to take billions of dollars and several years to clean up the plant).

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Saturday, May 7, 2011

Charlie Stross summarizes the latest report on the Fukushima Daiichi accident

Friday, May 6, 2011

Why companies do the things that they do -- sports sponsorship edition

Sometimes, though, these interests diverge and in these cases, it's always interesting to see how things break.

Take Yum! Brands' sponsorship of the Kentucky Derby.

Sometimes it's fairly easy to justify a sponsorship in terms of a business's bottom line. You can, for example, see why Frito-Lay would want viewers to associate Tostitos with the Fiesta Bowl. Other times the case is more difficult to make, as with AT&T and the Cotton Bowl. And then for some sponsorships, there is simply no case at all.

Yum owns KFC, Taco Bell and (for the moment) a number of smaller chains. There could certainly be a case for Yum sponsoring the "KFC Kentucky Derby" or even the "KFC/Taco Bell Kentucky Derby," but not the "Yum Kentucky Derby." Yum is not the relevant brand here. No one has ever said "Honey, you've had a hard day. Instead of cooking, let's load up the kids and head out to one of the many fine restaurants in the Yum! family."

You might possibly argue that sponsoring the Derby raises the profile of the company and therefore helps the stock, but there's a simpler and more logical explanation. Yum is based in Louisville, a town where much of the social season is based around the Derby. I suspect that the sponsorship has less to do with the company's stock price and more to do with its executives' social standing.

William Goldman once observed that one reason studio executives prefer to greenlight big-budget movies over smaller projects is that major films with big name casts give the executives something to talk about at parties.

You may not hear much about this in business and econ courses, but you certainly encounter it in real life.

Occam's barbershop -- Hollywood edition

Did quantitative analysis and movie modelling algorithms kill Anchorman 2?

The feeling of intrigue faded quite a bit when I followed the link and read this:

I was doing a short interview with Ferrell on Friday about his new movie, the indie drama "Everything Must Go," and toward the end Anchorman came up. I was excited to talk about the movie a bit with Ferrell -- especially since rumors of an Anchorman 2 have been circulating. Ferrell deflated my hopes on that score, however, at least for the time being: "We keep trying to explain to Paramount that there’s a lot of interest in a sequel, but they don’t seem to want to listen," Ferrell told me. "I’m not kidding, to the point that I’m openly talking about it with the press. At first we tried to be deferential but now we’re like, 'Yeah they don’t get it.'" This surprised me. With an $85 million domestic gross on a $26 million budget, the first Anchorman was hardly a cult hit. (The Paramount-Anchorman 2 beef is long-festering, it turns out: Deadline wrote a bit about the situation last year, and Adam McKay tweeted that the studio, which owns the rights to the film, "basically passed.") "They say when they model it and run the numbers, it doesn't add up for a sequel," Ferrell explained, "even though we have Steve and Paul and everyone on board to make it, and even though Steve" -- who recently left the cast of The Office -- "is free to make movies now."Let's do a really quick back-of-the-envelope run of the numbers and see what conclusion we reach.

1. Thanks to the deadline link we know that AM grossed 85mil domestically but only 5 overseas;

2. From the same source, we know that Ferrell, McKay and company are looking at a 70mil budget this time;

3. There is reason to question what side of the career parabola Ferrell is on, at least when he has to carry a movie. The last two films that were clearly Ferrell vehicles (thus excluding Megamind, the Other Guys and Step Brothers) were Land of the Lost (Budget $100 million, Gross revenue $68,777,554) and Semi-Pro (Budget $90 million, Gross revenue $43,884,904);

4. And we haven't even talked about marketing costs which have grown substantially in recent years, often exceeding production costs. The Hangover cost $35 million to make and $40 million to market. Assuming a similar push for Anchorman 2, we're talking a combined budget of around $110 million;

I have no doubt that the studio used various sophisticated models when looking at Anchorman 2. I suspect that's where they got the $40 million budget mentioned in the Deadline post. But it's worth noting that $40 million is awfully close to the number we derive from this decidedly unsophisticated formula:

Conservative Sequel Budget = Gross of first(90) - Marketing(40) - Overruns(10)

Given that (according to Wikipedia) no film starring Ferrell has ever grossed $200 million domestically, his biggest hit (Elf -- $173 million US) was back in 2003, his second biggest ( Talladega Nights) was five years ago and that no live-action film* starring Ferrell has broken $120 million domestically since then, it's not hard to see why a studio might be nervous about committing to $110 million in production and marketing.

Though people tend to talk about models in business with hushed, Oracle-of-Delphi tones, running the numbers usually gives us intuitive, common-sense answers -- often very close to our rough estimates. That's often the key to the models' greatest value -- by reminding us of the obvious, they keep us from building castles in the air using stockholders' money.

* Animated films are a bit of a special case. Megamind did good business, though not as the Incredibles, Up, Ice Age, and no one concluded from those films that Craig T. Nelson, Ed Asner, or Ray Romano could open a big-budget picture.

A conservative view on health care reform

Ultimately, all I want is some honesty in the public discourse on these issues, starting with three facts:

a. Yes, Medicare needs reforming,

b. Magical thinking about market forces is not going to work.** I have simply come to the point in thinking about all of this that I believe this assertion to be a dead end.

c. If all other OECD countries do a better job than we do in terms of cost and service, then perhaps we need to be realistic about that fact and look outside for viable models.***

By the way, I don’t pretend to have the answers to this conundrum, but I do think that the debate had to take place within logical parameters that address the actual situation at hand.

[some bridging text deleted to include the relevant footnotes. ed.]

**Understand: there was once a time when I, too, believed that markets in all things was the way to go. Empirical observation, and recognition of the reality around me, has altered my view on this. I still fundamentally believe in markets, but recognize that one size does not fit all.

***This is something else I have changed my view on over time. Indeed, I am not alone. See, for example, the following post from Reason‘s editor-in-chief, Matt Welch: Why I Prefer French Health Care (and yes, the libertarian magazine, Reason).

Now I am sympathetic to the argument that true free market health care hasn't been tried anytime recently. It has some issues that would have to be overcome. Externalities due to antibiotic overuse, for example, are not trivial to handle outside of regulation. Nor is it clear precisely how one would handle fraud in a way that would not be a legal nightmare.

But there are health care models that are both more and less functional than the current United States model. Why would we not look more closely at, for example, the German model before assuming that a massive social experiment makes sense?

Weekend Gaming -- special video edition

My first thought was that he shouldn't have made this a game of imperfect information.

My second thought was that I really need to get out this weekend.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

An actual quick one on broadcast TV

From the New York Times:

The Nielsen Company, which takes TV set ownership into account when it produces ratings, will tell television networks and advertisers on Tuesday that 96.7 percent of American households now own sets, down from 98.9 percent previously.Of course, you don't need 'new digital sets and antennas.' You need a forty dollar converter box (thirty if you shop around. Closer to twenty used). Any antenna that's UHF compatible will work (in other words, any antenna). I've used one from the 99 cents store -- worked fine.

There are two reasons for the decline, according to Nielsen. One is poverty: some low-income households no longer own TV sets, most likely because they cannot afford new digital sets and antennas.

Here are some more details:

Nielsen’s research into these newly TV-less households indicates that they generally have incomes under $20,000. “They are people at the bottom of the economic spectrum for whom, if the TV breaks, if the antenna blows off the roof, they have to think long and hard about what to do,” Ms. McDonough said. Most of these households do not have Internet access either. Many live in rural areas.*

I'm sure that some of these people can't afford a thirty dollar converter or a thrift-store TV, but there are certainly others who went without because they were misinformed about the costs. misinformed in part because reporters increasingly feel like it's their job to protect consumption rather than consumers.

* Having grown up in the Ozarks and taught in the Mississippi Delta, I can tell you from experience that rural areas face extraordinary challenges that are generally ignored if not openly mocked. For some of these people, the switch to digital really did end their access to free TV, greatly compounding problems with isolation. I'd like to respond to this with a major push to get high speed internet access to rural areas but that's a topic for another column.

A False Dichotomy

Consider a Libertarian's view of the French health care system:

What’s more, none of these anecdotes scratches the surface of France’s chief advantage, and the main reason socialized medicine remains a perennial temptation in this country: In France, you are covered, period. It doesn’t depend on your job, it doesn’t depend on a health maintenance organization, and it doesn’t depend on whether you filled out the paperwork right. Those who (like me) oppose ObamaCare, need to understand (also like me, unfortunately) what it’s like to be serially rejected by insurance companies even though you’re perfectly healthy. It’s an enraging, anxiety-inducing, indelible experience, one that both softens the intellectual ground for increased government intervention and produces active resentment toward anyone who argues that the U.S. has “the best health care in the world.”

The anecodates as to the efficiency of the system are pretty interesting as well. I can tell you from personal experience that the Canadians are unlikely to have the author's happy experience with universal short wait times.

So maybe we should be looking more broadly for examples?

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

"Teaching. You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means."

Like many in my position, I have about as much formal teaching training as I do formal gardening or cooking training. That's not to say that I can't cook a mean meal from stuff I've grown myself, but I've learned through seeing what works for others and trial and error. Teaching is no different, but I've been doing it formally (as in, full control over an entire course) for a shorter period of time. And whereas I see teaching as important, there also remains the fact that it can't be a priority for me at this stage of my career.I started out as a high school teacher, then went to grad school (in part to escape the worst principal I've ever run across), then did a four year stint as an instructor at a large university (making around 18K -- and yes, that's full time), then went back to high school teaching (and a 10K raise) then took advantage of the late Nineties economic boom and jumped to industry.

That said, for a variety of reasons (most notably, Broader Impacts, yo) I have gotten involved in a program aimed at producing teaching modules for grade 6-12 science classes. For each module there is a team of one person who teaches at a university and one person who teaches at either the middle or high school level. Nearly everyone involved has a formal background in education and is well-versed in the jargon that goes along with that training. In addition, the 6-12 teachers have an array of state requirements and testing that they have to conform with, creating a new layer of complexity.

The meetings we have as a group often make me feel a bit like I do when traveling in a country where I have a semi-decent grasp on the language - I know enough to follow the conversation and can clumsily contribute, but spend much of the time just trying to keep up. It's a fascinating experience for me seeing the approach to teaching that is taken at the 6-12 level and there's no shortage of elements that I could see employing in my own teaching. For that reason, I really think that I'm going to be taking as much or more out of this experience than I will be contributing, which is not necessarily what I thought when I agreed to join in.

My experiences at the university (lecturing to 150 students at a time, covering more advanced material, helping to supervise TAs) definitely made me a better high school teacher but I'd still have to say that teaching high school is better preparation for teaching college than teaching college is for teaching high school. In high school, you have to deal with students of widely varying abilities, most of whom have short attention spans and many of whom don't want to be in school at all.

This experience would be valuable to any teacher (even on a graduate level), as would the teacher training classes I took. There was, of course, an element of bullshit to some of those courses (though apparently not that different from what you get in Teach for America and far less pungent than much of what you encounter in the corporate world), but there were also a number of useful ideas, techniques and resources.

As Andrew Gelman observed, most people who teach college courses have never been formally introduced to any of these concepts. With luck they pick them up from other teachers or figure it out on their own.

You could make a case requiring some kind of teacher training for professors and TAs. Instead many in the reform movement seem determined to move in the other direction, dismissing the value of professional training for teachers and instead promoting a model of mass firings and high turnover in the search of 'natural teachers.'

You can probably guess what side of that debate I'm on.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

A kindness by omission

Actor (38 titles)

Various / Wayne Campbell / Dieter / …

Donald Q. Cashington

Shrek (voice) (singing voice) / Blind Mouse (voice) (singing voice)

Ari

Professor DeLong's history lesson for the day

Thank you. I remember, back when I was working for the Treasury, after one White House meeting Joseph Stiglitz—then one of the members of the President's Council of Economic Advisors—turned to me and said:Brad, not every question is best answered with a 10 minute economic history lecture.

But most are.

So let us start in the 1860s with the industrialization of America and the rise of the large scale business enterprise. There is then a law of bankruptcy: when a company does not pay you, and when you cannot work out terms, you go to a judge. The judge bangs his gave. The sheriff then auctions off the company's assets on the sidewalk and the company shuts down.

By the 1890s the judges in New York are saying: "Wait a minute! This makes no sense. Even though it is bankrupt, the New York Central Railroad is much more valuable as a going concern than if we simply pulled the individual rail segments off the roadbed and sold them off as ornamental ironwork. Moreover, there are lots of other stakeholders who rely on the operations of the New York Central--and even though they are not parties, there is a public interest in not having them suffer economic harm." So the judges change the law: they decide that when a large business enterprise goes bankrupt, we the judges will freeze its finances but let its operations continue while people negotiate and design and we approve a plan to restructure its debt and equity so that it can continue to operate. After judges took the lead legislators followed, and so we developed our current law of bankruptcy: when a company declares bankruptcy; we minimize the economic disruption by freezing and then sorting out its finances but letting its operations continue.

This system works pretty well in dealing with the bankruptcies of operating companies. Finances are frozen, debtor-in-possession financing is arranged, operations continue, the lawyers maneuver, and eventually a new financial superstructure is negotiated and plopped down on top of the operating company.

The problem is financial companies. They have no operations. They are all finance. When you freeze the finances the thing dies instantly.

Come the 1930s we face the waves of bank bankruptcies which make the Depression Great. The unemployment rate spikes to a peak non-farm level of 28%. We get the New Deal. The New Deal establishes the FDIC—which exists, among other things, to handle bank failures. When a bank fails the FDIC will go in, pay off its insured deposits, take over its assets and other liabilities, hopefully find a solvent and sound bank to take over the good-bank parts, and eat the remaining losses. This serves as an financial-sector analogue of Chapter 11. The hope was that with the FDIC we will never get into another situation like 1931 in which applying bankruptcy law to failing financial institutions produces general economic disaster.

Apparently, the lot of some economists is to be painfully condescending

The most curious thing about Mr Krugman's quasi-religious squeamishness about the "commercial transaction" is that it is normally the economist's lot to explain to the superstitious public the humanitarian benefits of bringing human life ever more within the cash nexus.Wilkinson's entire post is (unintentionally) interesting and you should definitely take a look at it (though you should also take a look at the rebuttals here and here), but for a distillation of the freshwater mindset, you really can't beat the line about 'the economist's lot.' (I suspect Wilkinson may have been going for humorous wording here but I doubt very much he was joking.)

For a less pithy though perhaps more instructive example, consider these comments Steve Levitt made on Marketplace:

One of the easiest ways to differentiate an economist from almost anyone else in society is to test them with repugnant ideas. Because economists, either by birth or by training, have their mind open, or skewed in just such a way that instead of thinking about whether something is right or wrong, they think about it in terms of whether it's efficient, whether it makes sense. And many of the things that are most repugnant are the things which are indeed quite efficient, but for other reasons -- subtle reasons, sometimes, reasons that are hard for people to understand -- are completely and utterly unacceptable.As I said at the time:

There are few thoughts more comforting than the idea that the people who disagree with you are overly emotional and are not thinking things through. We've all told ourselves something along these lines from time to time.

But can economists really make special claim to "whether [ideas] makes sense"? Particularly a Chicago School economist who has shown a strong inclination toward the kind of idealized models that have great aesthetic appeal but mixed track records? (This is the same intellectual movement that gave us rational addiction.)

When I disagree with Dr. Levitt, it's for one of the following reasons:

I question his analyses;

I question his assumptions;

I question the validity of his models.

Steve Levitt is a smart guy who has interesting ideas, but a number of intelligent, clear-headed individuals often disagree with him. Some of them are even economists.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Another quick one on broadcast TV

Living in Oregon, we have a lot of rainy days, and without the television for the kids to watch on occasion, it could get ugly. I must admit, I am also a primetime junkie, and that is my relaxation time, as well as the time when we all get to sit down and enjoy family time together. So despite how much this service costs, it is one that will always be a part of our budget.As I've mentioned before (a few times), not only is it still possible to watch TV for free, the technology has improved tremendously. The signal is digital and stations can carry multiple channels. I get over a hundred here in LA. In other words, my rabbit ears give me something about one or two steps up from basic cable.

For free.

Of course, a smaller urban center like, say, Portland, Oregon, will have fewer channels but as you can see here, the selection is still pretty good, particularly when compared to the thread-bare line-up from "Comcast Portland Regional - Standard" which not only offers fewer total channels, but also includes just two satellite stations, Discovery and WGN.

Unless you're a Cubs fan or you really like cable access, you'll probably get better programs through an antenna (for example, right now Portland broadcast TV is showing a Sundance winner that's not available on basic cable). You'll also have less image compression, you won't have to deal with the cable company and, just in case this point isn't plain enough, it's FREE!

I'm sure the author wasn't trying to give bad advice here. I'm certain she just didn't know about the other options, but of course that's the problem.

Between cable TV and the internet, consumers are feed an unprecedented stream of advice, but most of it is really bad, an ugly mix of lazy writing, inadequate-to-non-existent research and, worst of all, dependence on the very companies that provide the products and services being purchased.

One consequence of this is that consumers hear almost nothing about options that don't have the backing of a major industry. Another is that narratives are shaped to suit business interests. Check out almost any CNBC clip from say 2007 for excruciating examples.

Sunday, May 1, 2011

One of Krugman's talents

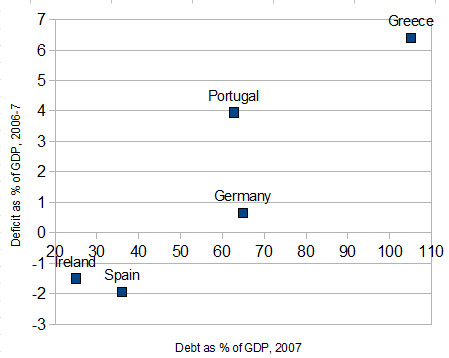

For example, take the profligate PIGS story -- the EU is in trouble mainly because four countries (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain) were reckless spendthrifts. It's a widespread explanation. Edward Glaeser even used a Spain specific variant of it to argue against high-speed rail.

In response to this, Krugman shows us the debt levels and deficits of these four countries (plus Germany as a reference point) on the eve of crisis:

As Krugman summarizes:

Yes, Greece had big debts and deficit. Portugal had a significant deficit, but debt no higher than Germany. And Ireland and Spain, which were actually in surplus just before the crisis, appeared to be paragons of fiscal responsibility — the former, said George Osborne, was

a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policymaking.

We know now that the apparent fiscal health of Ireland and Spain rested largely on housing bubbles — but that was by no means the official view at the time. And nothing I’ve seen explains how new fiscal rules would prevent a similar crisis from happening again.

Friday, April 29, 2011

Weekend Gaming -- perfecting the imperfect

When the subject of perfect information games comes up, you probably think of chess, checkers, go, possibly Othello/Reversi and, if you're really into board games, something obscure like Agon. When you think of games of imperfect information, the first things that come to mind are probably probably card games like poker or a board game with dice-determined moves like backgammon and, if you're of a nostalgic bent, dominoes.

We can always make a perfect game imperfect by adding a random element or some other form of hidden information. In the chess variant Kriegspiel, you don't know where your opponent's pieces are until you bump into them. The game was originally played with three boards and a referee but the advent of personal computing has greatly simplified the process.

For a less elaborate version of imperfect chess, try adding a die-roll condition to certain moves. For example, if you attempt to capture and roll a four or better, the capture is allowed, if you roll a two or a three, you return the pieces to were they were before the capture (in essence losing a turn) and if you roll a one, you lose the attacking piece. Even a fairly simple variant such as this can raise interesting strategic questions.

But what about going the other way? Can we modify the rules of familiar games of chance so that they become games of perfect information? As far as I can tell the answer is yes, usually by making them games of resource allocation.

I first tried playing around with perfecting games because I'd started playing dominoes with a bluesman friend of mine (which is a bit like playing cards with a man named Doc). In an attempt to level the odds, I suggested playing the game with all the dominoes face up. We would take turns picking the dominoes we wanted until all were selected then would play the game using the regular rules. (We didn't bother with scoring -- whoever went out first won -- but if you want a more traditional system of scoring, you'd probably want to base it on the number of dominoes left in the loser's hand)

I learned two things from this experiment: first, a bluesman can beat you at dominoes no matter how you jigger the rules; and second, dominoes with perfect information plays a great deal like the standard version.

Sadly dominoes is not played as widely as it once was but you can try something similar with dice games like backgammon. Here's one version.

Print the following repeatedly on a sheet of paper:

Each player gets as many sheets as needed. When it's your turn you choose a number, cross it out of the inverted pyramid then move your piece that many spaces. Once you've crossed out a number you can't use it again until you've crossed out all of the other numbers in the pyramid. Obviously this means you'll want to avoid situations like having a large number of pieces two or three spaces from home.

Each player gets as many sheets as needed. When it's your turn you choose a number, cross it out of the inverted pyramid then move your piece that many spaces. Once you've crossed out a number you can't use it again until you've crossed out all of the other numbers in the pyramid. Obviously this means you'll want to avoid situations like having a large number of pieces two or three spaces from home.If and when you cross off all of the numbers in one pyramid you start on the next. There's no limit to the number of pyramids you can go through. Other than that the rules are basically the same as those of regular backgammon except for a couple of modifications:

You can't land on the penultimate triangle (you'd need a one to get home and there are no ones in this variant);

If all your possible moves are blocked, you get to cross off two numbers instead of one (this discourages overly defensive play).

I haven't had a chance to field test this one, but it should be playable and serve as at least a starting point (let me know if you come up with something better). The same inverted pyramid sheet should be suitable for other dice based board games like parcheesi and maybe even Monopoly (though I'd have to give that one some thought).

I had meant to close with a perfected variant of poker but working out the rules is taking a bit longer than I expected. Maybe next week.

In the meantime, any ideas, improvement, additions?