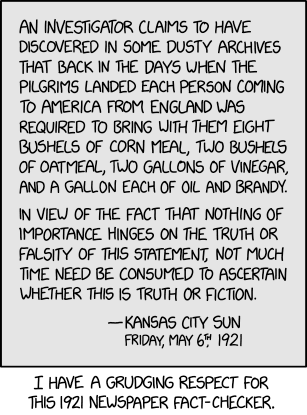

There's a genre that we've seen a lot recently. Someone (frequently with a Silicon Valley connection) will announce that we're finally on the verge of the development and/or the the widespread implementation of some innovation we've been promised for decades. Maglev vactrains, Martian colonies, and yes, even flying cars. These long awaited advances are always just around the corner, surprisingly cheap and almost ready because they depend on "existing technology."

I might be missing some obvious cases but it's difficult to think of an example where people spent years waiting for a breakthrough like this only to realize that, like Dorothy, they had the power all along. This one could well be different, but from what I'm seeing here, this seems to have less to do with advances in enabling technology and more to do with telling a story that people want to believe.

Even if you missed out on the Concorde, you may soon get a chance to fly in a supersonic airliner

By Eric Adams April 3, 2019

...

The J85 is GE’s workhorse military turbojet. Three of them will power Boom’s XB-1, a one-third-scale demonstration model of the $200 million, 55-seat carbon-fiber airliner the company hopes to see streaking across the sky at twice the speed of sound by 2025. It would be difficult to overstate the challenges Boom faces as it chases this goal and all the ways its plan could go wrong. Seventy-one years after Chuck Yeager punched through the sound barrier in the Bell X-1, the Concorde and the Soviet Union’s Tupolev Tu-144 remain the only airliners to achieve Mach speed. Neither worked out. The Tupolev mostly carried cargo, making just 102 flights with passengers. British Airways and Air France lost money on most Concorde trips despite exorbitant ticket prices and hefty government subsidies. They grounded the airplanes in 2003 after 27 years of glamorous—if fiscally strained—service.

The business case doesn’t appear much better today. Even as Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic make steady progress toward the day tourists will glimpse space through the porthole of a rocket ship, no one’s figured out how to make supersonic transport economically feasible. The problem lies in maximizing fuel efficiency while reducing engine noise and mitigating the sonic boom that inevitably accompanies anything moving faster than the speed of sound. When you throw in the requirement that this tech turn a profit, the puzzle is so fiendishly difficult to solve that Boeing and Airbus all but quit trying, launching precisely zero efforts since the Concorde’s last flight. Why bother, when airlines show little interest in jets that carry fewer people, burn more fuel, and can fly only over oceans because of the awful racket they make?

Given all this, the idea that a guy who’s best known for Amazon’s ad-buying tech could make supersonic work seems unlikely. [Blake] Scholl’s plan sounds absurd when you realize his aviation experience is limited to flying small planes. Yet he exudes the ebullient confidence typical of startup founders. “All the technology we need to do this already exists,” he says. “It’s safe, reliable, and efficient. So let’s take that same proven technology and make passenger’s lives more efficient too.”

For Scholl, the path to that vision is clear. Boom’s success hinges on developing a jet engine capable of achieving supersonic speeds without that fuel-guzzling afterburner. And he believes the boom problem won’t be a problem for his company. His business plan relies on convincing airlines that with new, more-efficient technology, they’ll make plenty of money shuttling business-class passengers across the Atlantic in three hours or the Pacific in six. The Virgin Group and Japan Airlines are among five carriers so intrigued by the idea that they’ve lined up to buy Boom’s airplanes, should they make it to production.

...

Boom is definitely going for glamorous. With its needle-like fuselage, pinpoint-sharp nose, and triangular delta wing, the Overture is one cool-looking craft. The planned interior is no less impressive. A virtual-reality demo offers a glimpse of what crossing the sky at 1,400 mph could be like. No one gets stuck in the middle because there’s just one passenger on either side of the aisle. There’s lots of leather, gleaming surfaces, and polished wood. Every one if its 55 seats [about half the capacity of the Concorde -- MP] faces a giant screen, and customers watch the scenery through large round windows. Scholl says the cabin will be so insulated that you won’t hear the engines. “Our goal is to exude tranquility,” he says.