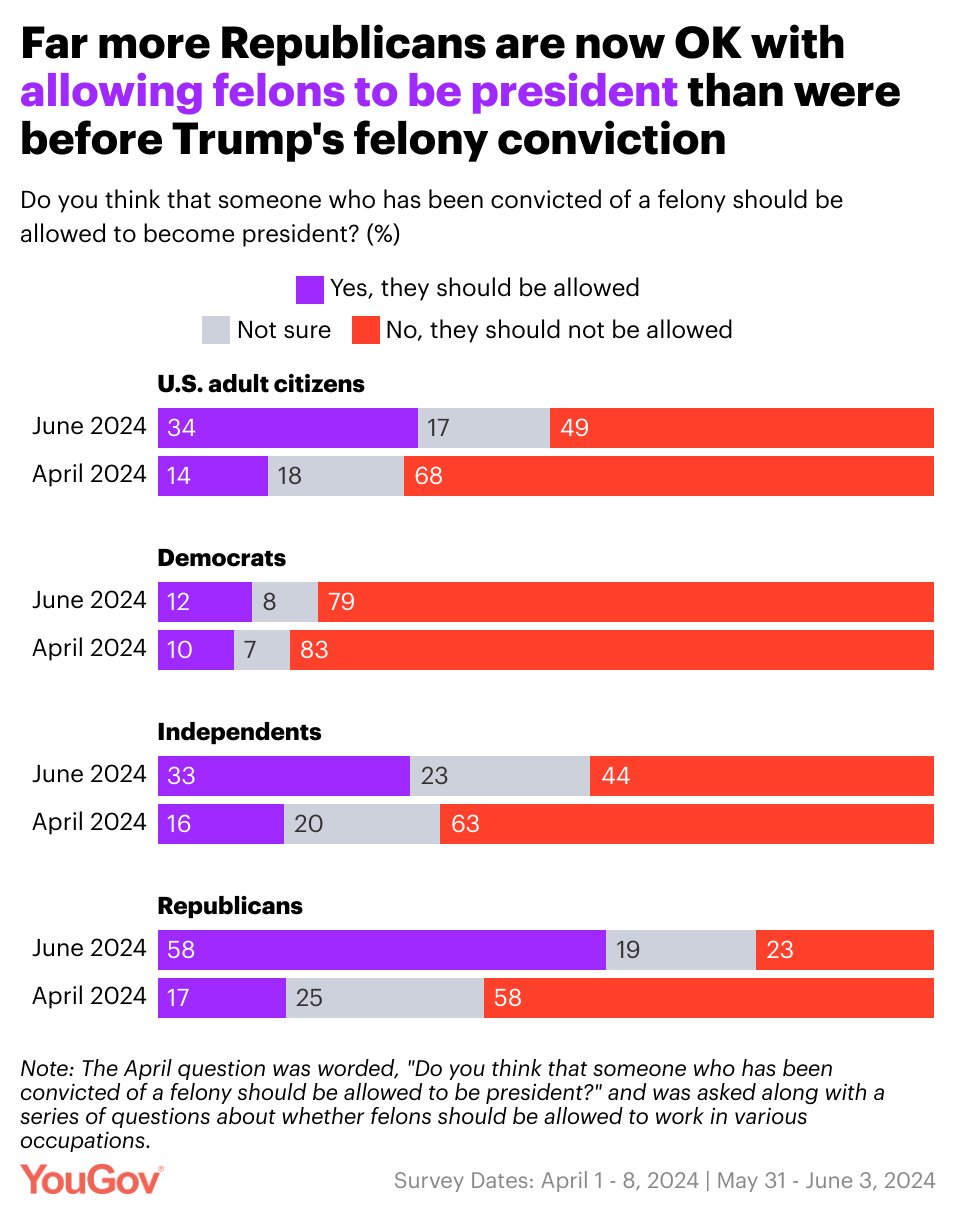

Happily, both of the nuclear units that were out of commission are back online producing 5,000 megawatts. Unhappily, there are still nearly 18,000 megawatts of coal and gas plants offline as this climate change-fueled heat wave sets in. #txclimate #txenergy pic.twitter.com/0XgsO1MjCS

— Doug Lewin (@douglewinenergy) May 25, 2024

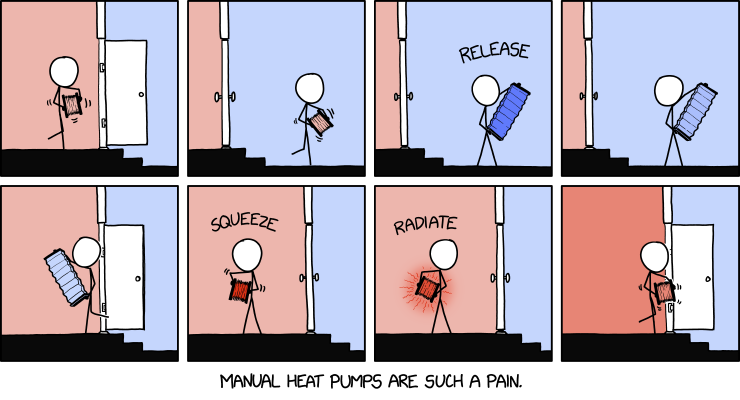

Put in XKCD terms, if you're trying to heat your house on a very cold day (or, reversing the process, cool it on a very hot day), you're going to have to squeeze really hard, which is going to put additional strain on the grid, but as far as your ground source system is concerned, the days are never very hot or cold. It's always in the mid-50s.

Of course, for the walls of your house it's still below zero or in the triple digits and you'll have to run the system more, but this will still go a long ways toward flattening out the spikes and avoiding the deadly power outages that have become a regular part of living in Texas.

Thursday, November 12, 2020

Ground source heat pumps are "the most energy-efficient, environmentally clean, and cost-effective space conditioning systems available," but maybe we can get journalists to talk about them anyway.

I'm joking but I'm not kidding.

If Elon Musk or some other Silicon Valley visionary proposed some laughable plan based on non-existent technology, reporters would be scheduling interviews within the hour, but a solution supported by experts based on mature, tested systems will get little to no coverage.

One of the biggest crises facing California is a failing electrical grid, particularly during summer heat waves which are going to continue becoming more frequent and severe as the planet warms. Ground source heat pumps and similar technology could greatly alleviate pressure on the grid, especially when coupled with roof top solar. On top of that, its efficiency reduces demand for fossil fuels.

If we're going solve our problems, we can't go on being disinterested in solutions.

From Wikipedia:

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has called ground source heat pumps the most energy-efficient, environmentally clean, and cost-effective space conditioning systems available. Heat pumps offer significant emission reductions potential, particularly where they are used for both heating and cooling and where the electricity is produced from renewable resources.

...

Ground source heat pumps are characterized by high capital costs and low operational costs compared to other HVAC systems. Their overall economic benefit depends primarily on the relative costs of electricity and fuels, which are highly variable over time and across the world. Based on recent prices, ground-source heat pumps currently have lower operational costs than any other conventional heating source almost everywhere in the world. Natural gas is the only fuel with competitive operational costs, and only in a handful of countries where it is exceptionally cheap, or where electricity is exceptionally expensive. In general, a homeowner may save anywhere from 20% to 60% annually on utilities by switching from an ordinary system to a ground-source system. However, many family size installations are reported to use much more electricity than their owners had expected from advertisements. This is often partly due to bad design or installation: Heat exchange capacity with groundwater is often too small, heating pipes in house floors are often too thin and too few, or heated floors are covered with wooden panels or carpets.

...

Capital costs may be offset by government subsidies, for example, Ontario offered $7000 for residential systems installed in the 2009 fiscal year. Some electric companies offer special rates to customers who install a ground-source heat pump for heating or cooling their building. Where electrical plants have larger loads during summer months and idle capacity in the winter, this increases electrical sales during the winter months. Heat pumps also lower the load peak during the summer due to the increased efficiency of heat pumps, thereby avoiding costly construction of new power plants. For the same reasons, other utility companies have started to pay for the installation of ground-source heat pumps at customer residences. They lease the systems to their customers for a monthly fee, at a net overall savings to the customer.