Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Target's targeting

I also have a similarly mixed reaction to Felix Salmon's comments on Duhigg's piece. I'm not questioning Salmon's understanding of the principles at work here (when it comes to analysing business problems, he's about the best we've got), but in this one case, I don't think he's supported his conclusion.

Check it out and judge for yourself.

Friday, February 17, 2012

Are incentives really so hard to set up?

So we should expect underinvestment in training of entry level workers absent some special arrangement like the TAP Writing Fellowship conceit. But it seems to me that to the extent that the training is transferrable the employee is gaining something of real value, and the employer now has the ability to reduce cash compensation accordingly. Employers need to choose between paying a premium for already-trained workers, or paying lower wages to less-trained workers but bearing training costs. But either approach is perfectly viable.So when would an employer not want to pay training wages? When they are convinced that the current demand is very short lived, is about the only thing I can come up with. In this case, the employer in the Yahoo article wants a skilled work force with flexible employment standards (i.e. willing to work in the short term), and not pay premium wages.

After all, it is not worth it for a young person to take a college program as a machinist today in the hopes that they would be employed for a short time at low wages tomorrow. The Karl Smith approach (outbid rivals and triple the wages) would make the positions sufficiently lucrative that some people would take the gamble that the wage bubble was a secular shift (and others, with the skills but employed elsewhere, might come back due to the high wages).

But the best path for the future is to develop a good policy for training. Sure, skilled workers often leave. But is it really that hard to build in retention incentives? Don't we do this for high level managers all of the time?

You might be amazed at what a $20,000 payout at the end of 2 years (or as a severance bonus if you are laid off before that time) would do to make the trainees "sticky". Even if they were worried about losing their job, the bonus would make them wait out the uncertainty.

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

Just move?

People who have chosen to live in a quiet area are probably people who have lower tolerance for that stress. If you're a renter, no problem: just move. But if you own, and the changes make your property harder to sell at the same time as they impair your enjoyment . . . well, it's not shocking that people resist.I actually mostly liked the piece, which focuses on the pros and cons of development (including some understandable but less than pure motives). But I want to stomp on the idea that renters can "just move". It is true that, as a college kid, it was possible for me to move with a van, some friends, and pizza expense. Of course, I had little furniture and was moving into places that catered to easy moves.

Add a few years and suddenly carrying a hundred boxed up several flights of stairs losses its allure. With a full household, moving is either expensive or a tremendous amount of work. It is also annoying to hunt for a new place and difficult to arrange things so that you do not end up paying rent on two places for at least a couple of weeks (the alternative for us middle aged folks is typically professional movers). It's accelerated by the need to clean a place out and the landlord's preference for no time without occupants.

So "just move" isn't as simple as it sounds . . .

Private Prisons

The Huffington Post reports that the for-profit prisons giant sent letters to 48 states offering to buy up their prisons in exchange for a 20-year management contract and the guarantee that the facilities would be at least 90 percent full.

Am I the only person who sees a potential issue with a 20 year contract that guarantees that prisons will be 90% full??? Seriously???

It is one thing to argue that we can make a decent 5 year projection based on current sentencing rules. But this puts huge barriers in the way of either sentencing reforms or improvements in crime prevention. Would the best case scenario not be a series of policing and social reforms that led to less criminal activity over time?

Furthermore, isn't the reason that we reward private business because they take risk? The idea of capitalism (creative destruction) is that good ideas are rewarded with profits and bad ideas lead to business failure. A state guarantee of customers (i.e. prisoners) over the course of a reasonable mortgage on these facilities is equivalent to removing all risk. So why should there be an expectation of profit?

And none of this addresses the difficulties in regulating a private contracter to insure that prisoner rights are not violated. After all, we trust the guards to report on violations that could extend a prison sentence; are we sure that there is no conflict of interest here?

I am not saying that all of these concerns cannot be addressed, but the basic idea seems suspect.

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

While on the subject of Apple's aspect dominance

Ryssdal: All right, so before we get to the big winners, tell me how you guys figure out who the winners are?

Sauer: For the last decade we've been watching each one of the No. 1 films at the box office each weekend and tracking all of the identifiable brands and product placements in each one of those films and then adding to a searchable database by brand, film, year, and everything.

...

Sauer: The No. 1 product that appeared in more of the U.S. top films last year than any other was Apple.

Ryssdal: Shocking. Shocking.

Sauer: Yeah, Apple appeared in almost twice as many No. 1 films as did the nearest brand.

Ryssdal: Now let me ask you this: Other than tapping into the, 'Oh my gosh, everybody loves Apple' zeitgeist, why do producers want Apple or Ford or whatever it is in their movie?

Sauer: Well there's a number of reasons. First, Apple has a very good... They don't pay for product placement, but they have a very good system.

Ryssdal: Wait. Wait. Wait. Wait. Wait. I thought the whole thing about product placement was that companies paid movie producers to use their stuff?

Sauer: I think that's what everybody thinks. But the vast majority of product placement, actually, there's no money changing hands really I would say. Apple has a good infrastructure for getting products to sets so that people can use it for free, so I guess Apple does pay in the sense that they supply free product. But the truth is a lot of products are used as shorthand in development for characters on-screen in ways that audiences don't always see.

...

Ryssdal: Is there a way to figure out, then, how much this is worth to Apple or whoever else it is?

Sauer: Valuation is still a hard thing to do in the industry, and there are different systems to do it. We worked this year for the first time with a group called Front Row Marketing and they came up with some big numbers. "Mission Impossible" for example, the value of the Apple product placement in that film was over $23 million.

Monday, February 13, 2012

Redistribution

The results are, again, somewhat of a disconnect. Of the 25 more liberal states, 16 of them are paying more in taxes than they get back. Of the 25 more conservative states, only 2 can say that. 23 of the 25 more conservative states are having wealth redistributed to them. I know people have a knee jerk response to dislike taxes and redistribution. But it seems like those most opposed to the idea of both of these things seem to be getting the most out of them.In a more general sense, I wonder if people have really thought out the consequences of less taxes. There are a lot of basic public goods (think roads) that simply require government intervention, at least if you want to avoid conflict over "road rights". After all, without a central authority to arbitrate conflict, it is unclear how things like long distance trade are going to occur (at least not without a lot more expense in armed guards).

In the same sense, there is a really odd property to people asking to be given less resources. Are we really sure that the link between taxes and programs is clear?

Some thoughts on patents

It has been pretended by some, (and in England especially,) that inventors have a natural and exclusive right to their inventions, and not merely for their own lives, but inheritable to their heirs. But while it is a moot question whether the origin of any kind of property is derived from nature at all, it would be singular to admit a natural and even an hereditary right to inventors. It is agreed by those who have seriously considered the subject, that no individual has, of natural right, a separate property in an acre of land, for instance. By an universal law, indeed, whatever, whether fixed or movable, belongs to all men equally and in common, is the property for the moment of him who occupies it; but when he relinquishes the occupation, the property goes with it. Stable ownership is the gift of social law, and is given late in the progress of society. It would be curious then, if an idea, the fugitive fermentation of an individual brain, could, of natural right, be claimed in exclusive and stable property. If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property. Society may give an exclusive right to the profits arising from them, as an encouragement to men to pursue ideas which may produce utility, but this may or may not be done, according to the will and convenience of the society, without claim or complaint from any body. Accordingly, it is a fact, as far as I am informed, that England was, until wecopied her, the only country on earth which ever, by a general law, gave a legal right to the exclusive use of an idea. In some other countries it is sometimes done, in a great case, and by a special and personal act, but, generally speaking, other nations have thought that these monopolies produce more embarrassment than advantage to society; and it may be observed that the nations which refuse monopolies of invention, are as fruitful as England in new and useful devices.

Considering the exclusive right to invention as given not of natural right, but for the benefit of society, I know well the difficulty of drawing a line between the things which are worth to the public the embarrassment of an exclusive patent, and those which are not. As a member of the patent board for several years, while the law authorized a board to grant or refuse patents, I saw with what slow progress a system of general rules could be matured. Some, however, were established by that board. One of these was, that a machine of which we were possessed, might be applied by every man to any use of which it is susceptible, and that this right ought not to be taken from him and given to a monopolist, because the first perhaps had occasion so to apply it. Thus a screw for crushing plaster might be employed for crushing corn-cobs. And a chain-pump for raising water might be used for raising wheat: this being merely a change of application. Another rule was that a change of material should not give title to a patent. As the making a ploughshare of cast rather than of wrought iron; a comb of iron instead of horn or of ivory, or the connecting buckets by a band of leather rather than of hemp or iron. A third was that a mere change of form should give no right to a patent, as a high-quartered shoe instead of a low one; a round hat instead of a three-square; or a square bucket instead of a round one. But for this rule, all the changes of fashion in dress would have been under the tax of patentees. These were among the rules which the uniform decisions of the board had already established, and under each of them Mr. Evans' patent would have been refused. First, because it was a mere change of application of the chain-pump, from raising water to raise wheat. Secondly, because the using a leathern instead of a hempen band, was a mere change of material; and thirdly, square buckets instead of round, are only a change of form, and the ancient forms, too, appear to have been indifferently square or round. But there were still abundance of cases which could not be brought under rule, until they should have presented themselves under all their aspects; and these investigations occupying more time of the members of the board than they could spare from higher duties, the whole was turned over to the judiciary, to be matured into a system, under which every one might know when his actions were safe and lawful. Instead of refusing a patent in the first instance, as the board was authorized to do, the patent now issues of course, subject to be declared void on such principles as should be established by the courts of law. This business, however, is but little analogous to their course of reading, since we might in vain turn over all the lubberly volumes of the law to find a single ray which would lighten the path of the mechanic or the mathematician. It is more within the information of a board of academical professors, and a previous refusal of patent would better guard our citizens against harrassment by law-suits. But England had given it to her judges, and the usual predominancy of her examples carried it to ours.

Thomas Jefferson, from a letter to Isaac McPherson

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Government as a business? A continuing exploration

This does, however, raise the interesting and oft-neglected point that corporate accounting and government accounting operate along very different principles. If I'm running a modestly profitable burrito company and decide I could be making even more money if I opened even more stores and so go sign some leases and spend a bunch of money building out the new kitchens, we don't register this as suddenly "spending" far exceeding "revenue" and freak out about the deficit. What we say is that the balance sheet now contains both more liabilities (debt to someone who loaned me the money) but also more assets (all the kitchen equipment I bought) and then my challenge is to earn a return on my investment in those assets before they depreciate (i.e., break). But a company that thought it had the opportunity to make a lot of high-value low-cost purchases would never avoid doing so simply because it might involve increasing its outstanding stock of debt.I think that this viewpoint could be really helpful if applied to the United States government. There is a lot of potential to invest in infrastructure right now, while prices are low. Sure, not all infrastructure works out and there is a lot of poor decision making in government process. But businesses make mistakes too. The trick is to, on average, make more good decisions than bad.

However, in the long run the stock of public goods (roads, bridges, powerlines, canals, and so forth) have been key to the success of a nation from ancient times. In the modern world, with the focus on human capital, I think education might have the same status as a good long term investment. Perhaps this is a case where we should think of government more like a business??

Sunday, February 5, 2012

Saturday, February 4, 2012

Apple's aspect dominance

When a successful, highly respected business dies unexpectedly, a bit of hyperbole is only natural. That said, the coverage has painted an awfully large picture of Steve Jobs' impact. The phrase "changed the world" has been difficult to avoid. (CNN Money doubled down on the theme following the headline "10 ways Steve Jobs changed the world" with the subtitle "There may never be another chief executive like him. Apple's former CEO and co-founder transformed the world's relationship with technology -- forever.")

We've also heard endless comparisons to Thomas Edison, which provide a useful bit of perspective. When Edison died, everyone with electricity or phone service (and many of those without) had his technology in their homes. Whether you went to the movies or the doctor, the legacy was unavoidable. By comparison, Apple, while a fantastically success company by most metrics, has a small footprint. Most of us don't have a Mac or an I-anything.

Apple's perceived footprint, however, is much larger. Based on news accounts and popular culture, you might get the impression that the typical American owns multiple Apple products. How did Apple manage this?

Some of the credit has to go the company's exceptionally effective branding (but that's a topic for another post). Then there's the kind products Apple makes, what we might call surface technology. Much, if not most, of the technology we use operates behind the scene. Personal electronics are easy to spot and are often used in public.

None of this takes away from Jobs accomplishments. It does, however, remind us that the press doesn't always do a good job keeping things in perspective.

Tin-can telephones and Apple's Patent Paradox

Acoustic telephones or 'string' telephones as they are often called, are misunderstood by many collectors. Since they transmit sound purely by mechanical means, they embody none of the pioneering electrical innovations that many collectors find so interesting. Truthfully though, very early telephones performed poorly; and during these years, the acoustic telephone represented a truly viable alternative for relatively short, private-line telephone systems.The Smithson website has a page on one of these phones:

Since they contained no electrical transmitting or receiving devices, they did not infringe on the Bell patents. Thus they were able to enter the telephone industry during the protected years of the late 1870s and 1880s, carving out a small niche for themselves.

In a trade catalog entitled Holcomb’s Improved Amplifying Telephone Illustrated Descriptive Circular, the telephone was described as “unquestionably one of the most marvelous and useful inventions of the nineteenth century.”I was reminded of these phones while I was working on a post about Apple. (If you write about Ddulites, you have to do a post on Apple sooner or later.) It struck me that the lag time between Apple and Apple imitators is remarkably brief. Bell's patents kept competitors at bay for long enough for alternatives like mechanical phones to get a foothold (albeit a small one). I also heard that part of the reason that the film industry moved west (first to Chicago, then to LA) was to put some distance between it and Edison's lawyers.

Holcomb’s mechanical telephones used galvanized steel cable-wire to transmit voice communications over distances of two miles. They were designed to meet the needs of businesses and “enable the busy man to save valuable time, to avoid vexatious delays, and to direct from his office the operations of employees at manufactory, mill, office, depot, or store . . . ”

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Ddulite Investors -- IPO editon

BLOCK: Now, we mentioned those 800 million Facebook users. A lot of people will be wondering in the papers today, do we get a sense of how profitable this company is?

HENN: Well, they had close to $4 billion in revenue, and they have very healthy margins. So, you know, that's a lot of money. But if Wall Street ends up valuing the company at something close to $100 billion, it will still make Facebook an extremely expensive company to invest in. Anant Sundaram is a professor at Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business.

DR. ANANT SUNDARAM: If I was a long-term investor thinking of this as a potential investment opportunity, I would hesitate.

HENN: Sundaram says to justify its price of Facebook shares that Facebook will sell at, it would need to grow at something like 30 percent a year for the next 10 years. And for today's investors to actually make money, it would have to grow faster than that. So to justify these kinds of valuations, Sundaram says Facebook and Google together would need to control something like a quarter of the entire global advertising market by the end of the next decade. So is that possible? Maybe. But he doesn't think it's likely.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Block that metaphor!

Obama wants to reward companies that create jobs here in the United States. One of the carrots is a tax credit for companies that move operations back here. Another would double tax breaks for high-tech factories making products here.Putting aside the argument that eliminating "a tax break for moving expenses when a company ships operations overseas" will encourage companies to ship operations overseas (is there a paragraph missing somewhere?), what caught my eye was the way Shlaes tortures this poor metaphor.

These are juicy carrots. But the sticks put forward by Obama are hefty. The president wants to eliminate a tax break for moving expenses when a company ships operations overseas. He also wants to close a tax loophole that allows companies to move some types of profits to overseas tax shelters.

The president figures that businesses will tolerate the pain of the sticks for the reward of the carrots. He thinks if he pokes the stick in one corner, they'll hop over to the corner where the carrots are.

But the trouble with this argument is that the U.S. economy is not a rabbit cage. And business people -- entrepreneurs especially -- don't respond well to prods from a stick. Any stick. If they get a glimpse of the rod, they'll leap away for sure -- but it might just be to somewhere outside the United States. Our cage. And the carrots of cheaper labor there overseas might even be tastier.

Maybe the president is forgetting the goal, which is making the economy grow faster. Enough carrots, and businesses will grow. And they'll create jobs. But pick up even just a few sticks, and you won't get recovery. Instead, we'll all be looking at an empty cage and asking: Where are the rabbits?

It doesn't help that the proverbial carrots and sticks were used to motivate proverbial mules and other large and stubborn beasts of burden. As an old country boy, I can tell you that getting big animals to go where they don't want to go is a challenge. I haven't had that much experience with bunnies, but I have to think it's a bit less daunting. I don't even believe I'd need a stick.

But Shlaes' odd allegorical choice is in keeping with the even odder dichotomy in the way conservative rhetoric has come to treat entrepreneurs and business leaders. Half the time they're bold and decisive figures, the spiritual descendants of our frontier forefathers; the rest of the time they are as delicate as a hothouse flower and as timid as a woodland creature (like, for example, a rabbit).

Shlaes has entrepreneurs leaping away at just "a glimpse" of a rod (and given that she describes closing a couple of tax loopholes as "hefty" penalty, it's fair to say that she really does mean it when she says any stick). Other conservative commentators have speculated that business leaders are slow to invest because they can't deal with the uncertainty caused by a possible return to Clinton era tax rates. We've even heard some argue that the recovery was slowed because the president keeps saying hurtful things about bankers and CEOs.

It's a bit like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde but with John Galt and Elmo.

Marketplace really needs to get Frum back.

Libertarians in space -- the sequel

Monday, January 30, 2012

The Devil's Candy -- movie bombs and college budgets

Salamon, already a well established journalist, was given almost unprecedented access to the production. I say 'almost' because there is one other similar book, Picture, by Lillian Ross of the New Yorker, which describes John Huston's filming of Stephen Crane's Red Badge of Courage. Huston's film has grown in critical stature over the years, but it was a notorious commercial flop, which should, perhaps, have been a warning to Brian DePalma and the other people behind Bonfire.

Of course, Hollywood is a world of its own, but there are some general lessons in The Devil's Candy. One is that enterprises have a right size and if you try to scale past that size, things can go very wrong. As DePalma (who deserves serious points for forthrightness) put it:

"The initial concept of it was incorrect. If you're going to do The Bonfire of the Vanities, you would have to make it a lot darker and more cynical, but because it was such an expensive movie we tried to humanize the Sherman McCoy character – a very unlikeable character, much like the character in The Magnificent Ambersons. We could have done that if we'd been making a low-budget movie, but this was a studio movie with Tom Hanks in it. We made a couple of choices that in retrospect were wrong. I think John Lithgow would have been a better choice for Sherman McCoy, because he would have got the blue-blood arrogance of the character."Another lesson is that, viewed individually, each of the disastrous decisions seemed completely reasonable. There's something almost Escher-like about the process: each decision seems to be a move up toward a better and more profitable film but the downward momentum simply accelerates, ending with a critically reviled movie that lost tens of millions of dollars. I suspect that survivors of similar fiascos in other fields would tell much the same story.

Finally there's the way that the failure to control costs in one area limits the ability (or willingness) to control it in other areas. You might that excessive spending on a cast would encourage producers to look for ways to spend less on something like catering, but the opposite often seems to happen when you have this kind of budget spiral. It's a delusional cousin of dynamic scoring: people internalize the idea that anything that might directly or indirectly improve box office performance will pay for itself, no matter how expensive it may be. Pretty soon you're bleeding money everywhere.

Ddulite Investors

I started out in the banking industry. My company used to broadly recruit from other banks so we had plenty of chances to compare stories about strategies that different banks used and this particular one stood out to me as an interesting way of handling investor complaints.

The bank in question was in the middle of a very good run, making a flood of money from its credit card line, but investors kept complaining that the bank was making all that money the wrong way. This was the height of the Internet boom but the bank was booking all of these profitable accounts through old-fashioned direct mail. If it wanted to maximize its stock price, the bank needed to start booking accounts online.

The trouble was that (at least at the time) issuing credit cards over the Internet was a horrible idea. The problem was fraud. With direct mail, the marketer decides who to contact and has various ways to check that a customer's card is in fact going to that customer. With a website, it was the potential customers who initiated contact and a stunning number of those potential customers were identity thieves.

The Internet was an excellent tool for account management, but the big institutional investors were adamant; they wanted to see the bank booking accounts online. Faced with the choice between unhappy investors and a disastrous business move, the company came up with a truly ingenious solution: they added a feature that let people who received a pre-approved credit card card offer fill out the application online.

Just to be absolutely clear, this service was limited to people who had been solicited by the bank and based on the response rates, the people who went online were basically the same people who would have applied anyway. From a net acquisitions standpoint, it had little or no impact.

From an investor relations standpoint, however, it accomplished a great deal. Everyone who filled out one of those applications and was approved* was counted as an online acquisition. Suddenly the bank was using this metric to bill itself as one of the leading Internet providers. This satisfied the investors (who had no idea how cosmetic the change was) and allowed the bank to continue to follow its highly profitable business plan (which was actually a great deal more sophisticated than the marketing techniques of many highly-touted Internet companies).

*'pre-approved' actually means 'almost pre-approved.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

California has good universities!

1. Harvard University (private)

2. Stanford University (private)

3. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) (private)

4. University of California, Berkeley (public)

5. University of Cambridge (British)

6. California Institute of Technology (private)

7. Princeton University (private)

8. Columbia University (private)

9. University of Chicago (private)

10. University of Oxford (British)

11. Yale University (private)

12. University of California, Los Angeles (public)

13. Cornell University (private)

14. University of Pennsylvania (private)

15. University of California, San Diego (public)

16. University of Washington (public)

17. University of California, San Francisco (public)

18. The Johns Hopkins University (private)

19. University of Wisconsin - Madison (public)

20. University College London (British)

Some interesting patterns immediately jump out. Of the top 20 schools, 17 are American, which is pretty impressive given the share of the world population held by the United States. Of the 17 American schools, six of them are public (which is amazing given how many resources the private schools have). Of the public schools, 4 of them are in California.

So why are we discussing the need to privatize California higher education, which combines extremely high quality with relatively low tuition? I mean seriously, is there no other public university system in the nation that we can focus on? Or is it merely that reformers want to destroy the example of well done public education?

The whole argument strikes me as insane.

Not sure Dean Dad caught the gist

President Obama has put higher education “on notice” that if we keep raising tuition, we’ll get our public funding cut.The post doesn't include a link but I assume he's referring to this (emphasis added):

To which I say, huh?

We’ve had our public funding cut already. Since 2008, an uninterrupted series of cuts has been the direct cause of severe tuition increases for public higher ed. If you want to stop the tuition increases, the first thing to do is to require the states to restore and then maintain realistic funding levels. (When referring to a point in time, the usual term is a “maintenance of effort” requirement. Otherwise, it can be set as a “grant in aid.”) When the states have cut back, colleges have turned to the Feds through the indirect means of raising tuition, much of which is funded by Federal financial aid.

Of course, it’s not enough for us to increase student aid. We can’t just keep subsidizing skyrocketing tuition; we’ll run out of money. States also need to do their part, by making higher education a higher priority in their budgets. And colleges and universities have to do their part by working to keep costs down. Recently, I spoke with a group of college presidents who’ve done just that. Some schools re-design courses to help students finish more quickly. Some use better technology. The point is, it’s possible. So let me put colleges and universities on notice: If you can’t stop tuition from going up, the funding you get from taxpayers will go down. Higher education can’t be a luxury – it’s an economic imperative that every family in America should be able to afford.I don't often find myself defending the President's education policies (too many movement reformers have his ear), but I think he did a good job hitting the main points here and Dean Dad could have done a better job reflecting that.

Saturday, January 28, 2012

I think we need to understand college cost structures better

College Costs and Quality? I rather suspect that my experience as a university professor is pretty typical, although certainly there are much more dramatic. Over the past 15 years my real (inflation adjusted - just using the CPI) salary has fallen16.5%, 831/2 cents on the dollar, not counting various costs the universities have shifted to the faculty (and not accounting for the fact, which nobody seems to when considering the situation of seniors in our society, that as one ages medical costs are an increasing proportion of expenditures, and they have been rising sharply). The "special" equipment I need is a decent laptop computer, the provision to our department members of which has enabled them to reduce secretarial support. The courses I used to teach as seminars are now in amphitheaters, and, while the substantial advances in IT (when the equipment works) have certainly improved that teaching environment, it is still most certainly not comparable to the learning in the interaction, and professor attention to individual students, of the seminar format. Moreover, tests are inadequate measures of learning, and abysmal measures of creativity, yet evaluating and commenting on papers and projects in classes of this amphitheater size is simply physically impossible, and beyond the capabilities of teaching assistants, in my field anyway. Indeed, I suspect over emphasis on exams (and standardized tests) may actually stunt creativity (assignments here for psychologists and cognitive scientists).I think that there is a real need to understand why costs of college are escalating. It seems to be a complex problem and I have begun to suspect that simple explanations are likely to be inadequate. Some of the issues seem to be related to new services (e.g. information technology, increased reporting mandates, student services). But it is remarkable that salaries for the most expensive workers can drop at the same time as costs are rapidly rising.

Some of this is likely due to loss of state funding. But private schools have also grown more expensive with time and this cannot be solely attributed to changes in funding.

I would love to see a time series of university budgets, in real dollars, to try and understand this issue better.

Friday, January 27, 2012

I was surprised by the lack of comments on this

President Obama has put higher education “on notice” that if we keep raising tuition, we’ll get our public funding cut.

To which I say, huh?

We’ve had our public funding cut already. Since 2008, an uninterrupted series of cuts has been the direct cause of severe tuition increases for public higher ed. If you want to stop the tuition increases, the first thing to do is to require the states to restore and then maintain realistic funding levels. (When referring to a point in time, the usual term is a “maintenance of effort” requirement. Otherwise, it can be set as a “grant in aid.”) When the states have cut back, colleges have turned to the Feds through the indirect means of raising tuition, much of which is funded by Federal financial aid.I think we really need to make a distinction between public and private education here. Public schools, like in California, have had huge funding cuts that led to large percentage increases in tuition. But, in absolute terms, the increases are small compared to the amount of tuition charged at private schools (like Stanford, which is in the same state).

In public education the finding cuts are causally connected to cost increases. But I am not sure the University of California is really the problem in terms of unsustainable educational costs. True, universities are expensive and I have been amazed at the cost increases. But serious cuts in state support needs to be part of the overall picture to really understand what is going on. Education (especially affordable education) is a public good and should be treated as such.

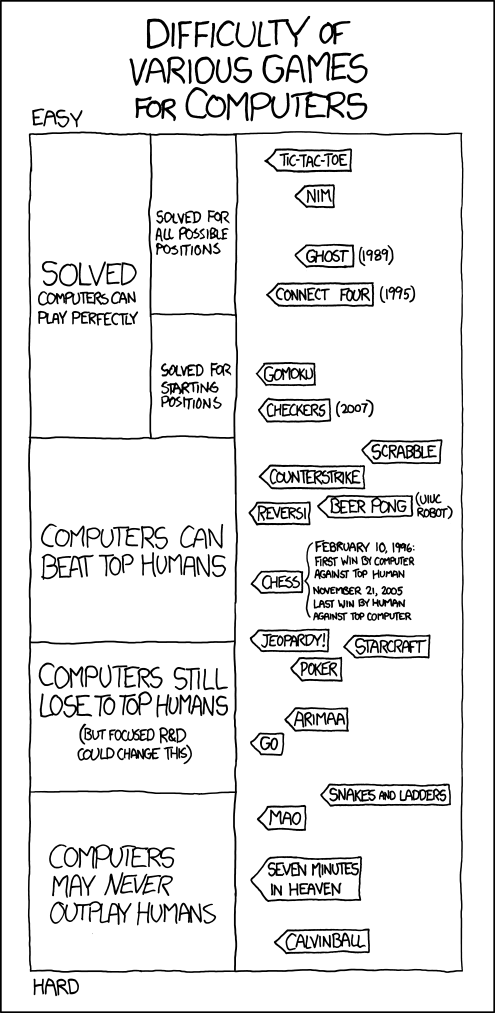

Gaming

Enjoy.

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

I am confused about carried interest

First, $13 million of the total was carried interest, which gets taxed like capital gains but is really just commissions that receive special treatment for no good reason. No profits taxes were paid on that income; right there, a minimally defensible tax code would have levied $2.6 million more in taxes on Romney.

I am completely agnostic as to the identity of the person in question -- it would be just as concerning if Barack Obama had millions in carried interest in his tax forms. The real question is how this exemption (which is commissions) can stimulate economic growth. I understand the argument for preferential treatment of capital gains. I even understand how capital gains can end up making moving between houses expensive for no really good reason. So I comprehend how this can be a matter of academic debate.

But can anyone explain why commissions should get preferential tax treatment?

Monday, January 23, 2012

Admittedly an extreme case

You know the sort of thing I'm talking about, stories with titles like:

Newt Gingrich's three marriages mean he might make a strong president -- really

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Student Loans and Emergencies

As a resident manager of David’s House , a beautiful private nonprofit home away from home for families of sick children at Dartmouth Hitchcock Hospital , like a Ronald McDonald House, one of the saddest and most frustrating things I saw was student loan collectors that would not work with parents who had run out of forbearance time to reduce or temporarily waive student loan payments despite their medical emergencies. Even the federal government will operate this way when a student loan goes into collections. Will not work with the debtor at all. We had collection agencies tracking down parents at our facility because, of course, parents who were living there temporarily needed to make the phone number known instead of keeping it confidential. The student loan crisis: another problem that you economists should address.

The decision to make student loans immune to bankruptcy is going to be a problem in the long run, at least so long as the totals become so high. I meet a surprising number of students with > $100,000 in debt. It's one thing to allow large debt to occur as part of developing human capital. But the punishment meted out to people when their lives go wrong seems way disproportionate to the decision to borrow. This is even more true when you look at the employment rate among Americans without a college degree.

It makes education into a high stakes gamble (at for those who are not already wealthy) instead of a public good that we provide to improve human capital.

Tax Reform

Consider the tax on gasoline. Driving your car is associated with various adverse side effects, which economists call externalities. These include traffic congestion, accidents, local pollution and global climate change. If the tax on gasoline were higher, people would alter their behavior to drive less. They would be more likely to take public transportation, use car pools or live closer to work. The incentives they face when deciding how much to drive would more closely match the true social costs and benefits.And this:

Consider the deduction for mortgage interest . . . Subsidies to homeowners are, in effect, penalties on renters — after all, someone has to pick up the tab. But there is nothing wrong with renting. And once one acknowledges that renters are poorer, on average, than homeowners, the mortgage interest deduction becomes even harder to justify.

These are the sorts of places that tax reform might make a significant difference in building a better system. It is true that tax reform in these areas would be politically unpopular. But, in the long run, it might make for a much better and more transparent tax system.

Saturday, January 21, 2012

Why I believe in safety nets

Who among the parents fighting so hard to get their kids into a good school is going to volunteer to have their kid give up the slot in the upper middle class? People are willing to accept a certain amount of slippage, but only as long as it comes with added job security (government) or special fulfillment (the ministry, the arts)--and even in the latter cases, Mom and Dad will often be strenuously arguing against following your calling. But how many doctors and lawyers would simply glumly accept it if you told them that sorry, junior's going to be an intermittently employed long-haul trucker, and your darling daughter is going to work the supermarket checkout, because all the more lucrative and interesting slots went to smarter and more talented people?

The lack of a safety net makes falling in social status a serious problem. When basic medical care is linked to being a productive member of the middle class, people are willing to make enormous sacrifices to protect themselves from falling in social class. If we mitigate the problems and torments of extreme poverty then maybe it won't be seen as terrible to have people shift around in social class.

Now it is true that my focus is on absolute levels of deprivation. But if the you can be poor with dignity and have basic needs met then maybe that will make us a little more willing to address inequality in general.

Friday, January 20, 2012

Copyrights and patents are intrusive government regulations

This doesn't mean intellectual property laws are bad. They aren't. Society could not function well without them. What this does mean is that these laws have a cost. They distort markets, raise prices, divert resources from productive areas to legal departments and inhibit creative destruction and the founding of new businesses. We have to balance these costs against the social benefits of encouraging creation and dissemination.

Recently, though, we've lost sight of that need for balance, in no small part because those costs are born by consumers and small companies that lack the wherewithal for PR and lobbying. In the area of copyrights (patents are a subject for another day), we've allowed ludicrous extensions, let lawyers grab works from the public domain, retroactively granted copyrights to works whose creators have been dead for decades, and tried to greatly restrict the concept of fair use.

It's important to remember that the very notion of owning an idea is a useful absurdity. Ideas are intangible and indistinct with no real demarcation from other ideas. It is tremendously useful for a society to encourage creativity and give creators a protected period to disseminate their works, but if we start thinking of protecting intellectual property as an end to itself, all we have left is the absurdity.

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Works moved out of the public domain?

The Supreme Court on Wednesday upheld a federal law that restored copyright protection to works that had entered the public domain. By a 6-to-2 vote, the justices rejected arguments based on the First Amendment and the Constitution’s copyright clause, saying that the public domain was not “a category of constitutional significance” and that copyright protections might be expanded even if they did not create incentives for new works to be created. The case, Golan v. Holder, No. 10-545, considered a 1994 law enacted to carry out an international convention. The law applied mainly to works first published abroad from 1923 to 1989 that had earlier not been eligible for copyright protection under American law, including films by Alfred Hitchcock, books by C. S. Lewis and Virginia Woolf, symphonies by Prokofiev and Stravinsky and paintings by Picasso.How exactly does this act to promote the creation of new works? Any possible incentive to the creaters is long past. Notice that this period ends in 1989 -- how many people would have created more works jsut in case they could get copyright protective in a foreign market 23 years later?

I am not against intellectual property rights (rather the converse) but I question is need for such long term protection for pieces that are decades old. At some point the public domain is the right place for these older works, as it gives them a chance to be rediscovered by people looking for inexpensive content. That is probably a better legacy for the creators than any minimal stream of royalties could be at this late date.

Another post on Unions

Jordan Weissmann, the author of the Atlantic article, focuses on the salaries of the teachers (mean of $52K) and the deadlock on contract negotiations. In some ways, I think everyone is missing the big picture. Teachers are professionals who work for a contract. We do not micromanage the compensation packages of hedge fund managers, either. It is true that teachers are paid directly by the government. But the carried interest exemption (which sets tax rates at 15%) is just as much of a decision to spend money.

After all, selectively taxing one group less is the same as a subsidy.

Put this another way, we could pay teachers less if we made their salaries exempt from income tax. Now this does not mean that specific benefits can't be renegotiated. Nor do I want to deny the reality of increasing health care costs (which are a problem everywhere in the United States right now) which can make benefits that were once reasonable seem excessive. But is it really constructive to focus on whether the teacher's health care plan is correctly designed as a matter of public policy. Or should be be looking at the long term drivers of malaise in our society.

Of course, looking at the long term drivers of malaise means facing up to our low tax rates (guarenteed to be a painful discussion) and dealing with the rate of growth in medical costs.

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Reading assignments

Felix Salmon's take on a subject is always appreciated, particularly when he's focusing on a topic we try to keep an eye on (like for-profit schools).

And staying on the education beat, Dana Goldstein collects almost two centuries worth of teacher-bashing.

The last few news cycles have brought lots of pieces about Bain. A few of them have been really interesting.

I've come across a site for the truly hardcore pop culture nerds, particularly those obsessed with stand-up comedy. There's even an intellectual property angle.

And I have got to make time for this.

Monday, January 16, 2012

Worthwhile Canadian Post

Frontiers in Car development

All told, the changes may not best the leap from horses to cars, but they are big enough to undermine many of the legal systems we rely on for things like insurance, not to mention criminal law. If a car doesn't require a driver, can a 12-year-old "drive" to his friend's house? Can a drunk person drive home from a bar? How will insurance work if people share driverless cars? Courts and legislators will be sorting those out for years to come.

Actually, I kind of like the idea of cars that can take home intoxicated people safely. Living in a community with a lot of college students, sub-urban road planning, and a lot of bars, I see a lot of accidents. I worry that some of them might have been prevented with better transportation options. Now, obviously, my preference would be improvements in public transit. But driverless cars might well be a good alternative for people who would like to go out but have limited options for coming home.

Tyler Cowen on Health Care

The U.S. median wage for 2010 was $26,363. The average health care insurance premium today is over $15,000 and by 2021 it may be headed to $32,000 or so (admittedly that estimate is based on extrapolation). Therein lies the problem

Of course, to me this number just argues for single payer health care (which can bend the curve) and innovation to try and bring cost controls to the medical profession. Now is it not contradictory to argue for both innovation and greater government control? In a sense it is, except that the market has formidable barriers to entry that cannot be easily be navigated.

So, for example, a team of nurses and a pharmacist could not form a company to treat twenty and thirty years for their minor health issues. Nor do we have a clear distinction between major medical insurance (what if I end up in the ER) versus standard health care insurance (which removes the cost from the patient and is subsidized by the government).

On the other hand, maybe I am discounting the possible benefits of the exchanges?

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Health Care on Nights and Weekends

Aaron Carroll has a smart point about the limitations of the current office visit model of health care. He looks at the percentage of people who have trouble getting care on nights and weekends. It seems that we don't do especially well, even on international standards:

Yeah, we beat Canada. But we lose to almost every other country. Almost two thirds of Americans have trouble getting care on nights, weekends, and holidays. You know what? A significant amount of the week is filled with nights, weekends, and holidays. Especially if you don’t want to miss work. It’s fine to believe that people should try and see the doctor in the office. But if you want that to happen, then you need the office to be available. If retail clinics do a much better job in that respect, you can’t complain when people make use of them

I think that there are two points of interest here. One, while Canada has a laudable health care system, it has flaws too and so a straight out effort to clone it might overlook opportunities to do better.

The second is that these visits don't even have to be expensive. Nurses in small retail clinics (you do not even have to have a medical doctor) could diagnose a lot of minor conditions, refer patients to emergency rooms in a crisis, and give instructions for minor care. Now consider that Pharmacies are open 24 hours in a lot of places. They have a medical professional with a doctorate behind the counter who is an expert on medications. Why could pharmacists not prescribe based on the Nurse's diagnosis. Both pharmacists and nurses are cheaper than medical doctors, used to shift work, and highly trained professionals.

Why could they not do a lot more to simultaneously reduce costs (as clinics are inexpensive, provide an alternative to hyper-expensive emergency rooms, and could get patients seen faster) and improve service (would you spend $75 to get easy treatment for an infection at 11 pm on a Saturday night?).

Why aren't me trying out these sorts of innovations?

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Thinking about past and future

Friday, January 13, 2012

I thought I was done with IP stories for a while

Right now, if you want to read the published results of the biomedical research that your own tax dollars paid for, all you have to do is visit the digital archive [1] of the National Institutes of Health. There you’ll find thousands of articles on the latest discoveries in medicine and disease, all free of charge.

A new bill in Congress wants to make you pay for that, thank you very much. The Research Works Act [2] would prohibit the NIH from requiring scientists to submit their articles to the online database. Taxpayers would have to shell out $15 to $35 [3] to get behind a publisher’s paid site to read the full research results. A Scientific American blog said it amounts to paying twice.

Things I wish I had time to write about -- the growth fetish

If I had time, I'd really like to explore the connection between this and an earlier OE post on the growth fetish:Private equity is by no means unique in this respect: it happens at pretty much every public company, too. John Gapper, today, has a column about the way it destroys values at struggling technology companies:

Most public companies are run by people who hate folding ’em, and instead keep returning to the shareholders and bondholders for more chips…

Few senior executives, when debating options for a technology company in decline, admit defeat and run it modestly. Instead, they cast around for businesses to buy, or try to hurdle the chasm with what they have got. Sometimes they succeed but often they don’t, wasting a lot of money along the way.

It goes against their instincts to concede that the odds are so stacked against them that it is not worth the gamble. Mr Perez would have faced a hostile audience if he’d admitted it to the citizens of Rochester, Kodak’s company town in New York, but its investors would have benefited.

At many companies, then, both public and private, the optimal course of action is a modest one — run the business so that it makes a reasonable profit, and can continue to operate indefinitely. If you chase after growth, you often end up in bankruptcy: that’s one reason why the oldest companies in the world are all family-run. Families, unlike public companies or private-equity shops, don’t need growth: they’re more interested in looking after their business over the very, very long run.

It's obvious that our economy is suffering from a lack of growth but for a while now I've come to suspect that in a more limited but still dangerous sense we also overvalue growth and that this bias has distorted the market and sometimes encouraged executives to pursue suboptimal strategies (such as Border's attempt to expand into the British market).

Think of it this way, if we ignore all those questions about stakeholders and the larger impact of a company, you can boil the value of a business down to a single scalar: just take the profits over the lifetime of a company and apply an appropriate discount function (not trivial but certainly doable). The goal of a company's management is to maximize this number and the goal of the market is to assign a price to the company that accurately reflects that number.

The first part of the hypothesis is that there are different possible growth curves associated with a business and, ignoring the unlikely possibility of a tie, there is a particular curve that optimizes profits for a particular business. In other words, some companies are better off growing rapidly; some are better off with slow or deferred growth; some are better off simply staying at the same level; and some are better off being allowed to slowly contract.

It's not difficult to come up with examples of ill-conceived expansions. Growth almost always entails numerous risks for an established company. Costs increase and generally debt does as well. Scalability is usually a concern. And perhaps most importantly, growth usually entails moving into an area where you probably don't know what the hell you're doing. I recall Peter Lynch (certainly a fan of growth stocks) warning investors to put off buying into chains until the businesses had demonstrated the ability to set up successful operations in other cities.

But the idea of getting in on a fast-growing company is still tremendously attractive, appealing enough to unduly influence people's judgement (and no, I don't see any reason to mangle a sentence just to keep an infinitive in one piece). For reasons that merit a post of their own (GE will be mentioned), that natural bias toward growth companies has metastasised into a pervasive fetish.

This bias does more than inflate the prices of certain stocks; it pressures people running companies to make all sorts of bad decisions from moving into markets where you don't belong (Borders) to pumping up market share with unprofitable customers (Groupon) to overpaying for acquisitions (too many examples to mention).

As mentioned before we need to speed up the growth of our economy, but those pro-growth policies have to start with a realistic vision of how business works and a reasonable expectation of what we can expect growth to do (not, for example, to alleviate the need for more saving and a good social safety net). Fantasies of easy and unlimited wealth are part of what got us into this mess. They certainly aren't going to help us get out of it.

Things I wish I had time to write about -- the future that was

Check out this fascinating series of predictions from the Saturday Evening Post circa 1900:

Photographs will reproduce all of nature’s colors… [They will be transmitted] from any distance. If there be a battle in China a hundred years hence, snapshots of its most striking events will be published in the newspapers an hour later.

Wireless telephone and telegraph circuits will span the world. A husband in the middle of the Atlantic will be able to converse with his wife sitting in her boudoir in Chicago. We will be able to telephone to China quite as readily as we now talk from New York to Brooklyn.

Man will see around the world. Persons and things of all kinds will be brought within focus of cameras connected electrically with screens at opposite ends of circuits, thousands of miles at a span.

Rising early to build the furnace fire will be a task of the olden times. Homes will have no chimneys, because no smoke will be created within their walls.

Refrigerators will keep great quantities of food fresh for long intervals.

Fast-flying refrigerators on land and sea will bring delicious fruits from the tropics and southern temperate zone within a few days. The farmers of South America… whose seasons are directly opposite to ours, will thus supply us in winter with fresh summer foods which cannot be grown here.

Thursday, January 12, 2012

Once again a knowledge of obscure pop culture saves the day

I was reminded of threats when I came across this section of Felix Salmon's latest instalment of the adventures of Ben Stein:

But my favorite bit of the complaint is where he complains that the ad which did end up running, featuring Peter Morici, is “an explicit misappropriation of Ben Stein’s likeness and persona, which is an explicit violation of Ben Stein’s rights of privacy and of publicity, barred by California law”.

In other words, this ad, while it might look to all the world as though it features a real economist who’s much more qualified on such matters than Ben Stein, is in fact an illegal violation of Ben Stein’s privacy, which uses the likeness of Ben Stein. Maybe Stein thinks that Morici should wear a long blonde wig, or something, to make him look less Stein-esque?

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Nice Observation

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

With this special offer, you can watch the Super Bowl on your laptop absolutely for free!!

I recently heard a technology reporter talking about how big it would be when someone finally figured out a commercially viable way for people to watch the Super Bowl on their computers. It struck me as a perfect ddulite moment, gushing over an anticipated technology while ignoring an existing one that had all the same essential features.

This tendency to prefer next year's toy to this year's tool is one of the ddulites' costliest traits because it leaves good, useful technology under-recognized and under-utilized. Waiting for the next big thing (like hydrogen fuel-cells or geo-engineering) can cause us to put off implementing existing technologies (plug-in hybrids, ground-source heating and cooling, etc.).

Sunday, January 8, 2012

What I don't like about this graph

Don't get me wrong. This Wikipedia graph carries a lot of information -- I use it all the time -- but there's a counter-intuitive quality about it that bothers me and I have no idea how to fix it.

Don't get me wrong. This Wikipedia graph carries a lot of information -- I use it all the time -- but there's a counter-intuitive quality about it that bothers me and I have no idea how to fix it.The problem is that changes in the x-axis mean more or less the opposite of changes in the y-axis. Smaller intervals between new laws and larger jumps in duration both indicate increased copyright protection.

This wouldn't be a problem if we were plotting these with a line -- with lines we're used to thinking in terms of slope -- but here the natural impulse is to think in terms of area, thus making the 1976 and 1998 laws look like fairly minor changes.

One more complaint, all but one of the states had copyright laws before 1790 so the law passed that year was more of a formalization than an extension. For most of the states, there was a period of almost fifty years without a major extension. The twenty-two year interval before the 1998 act really was exceptionally short.

Intellectual property and business life-cycles

A while back, we had a post arguing that long extensions for copyrights don't seem to produce increased value in properties created after the extension, but what about the costs of an extension? And who pays it?

New/small media companies tend to make extensive use of the public domain (often entailing a rather liberal reading of the 'public' part). The public domain allows a company with limited resources to quickly and cheaply come up with a marketable line of products which can sustain the company until it can generate a sufficient number of original, established properties.

Many major media companies have gotten their start mining the public domain, none more humbly than Fawcett. At its height, the company had magazines that peaked at a combined circulation of ten million a month in newsstand sales, comics that outsold Superman, and the legendary Gold Medal line of paperbacks. All of this started with a cheaply printed joke magazine called Captain Billy's Whiz Bang

Of course, Wilford Fawcett couldn't have reimbursed the unknown authors of those jokes even if he had wanted to. Disney, on the other hand, built its first success on a a title that was arguably still under copyright.

Mickey had been Disney's biggest hit but he wasn't their first. The studio had established itself with a series of comedies in the early Twenties about a live-action little girl named Alice who found herself in an animated wonderland. In case anyone missed the connection, the debut was actually called "Alice's Wonderland." The Alice Comedies were the series that allowed Disney to leave Kansas and set up his Hollywood studio.Another company that went from near bankruptcy to media powerhouse was a third tier comics publisher that had finally settled on the name Marvel. The company's turnaround is the stuff of a great case study (though MBA candidates should be warned, Stan Lee's memoirs can be slightly less credible than his comics). Not surprisingly, one element of that turnaround was a loose reading of copyright laws.

For context, Lewis Carroll published the Alice books, Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, in 1865 and 1871 and died in 1898. Even under the law that preceded the Mouse Protection Act, Alice would have been the property of Carroll's estate and "Alice's Wonderland" was a far more clear-cut example of infringement than were many of the cases Disney has pursued over the years.

In other words, if present laws and attitudes about intellectual property had been around in the Twenties, the company that lobbied hardest for them might never have existed.

Comic book writer and historian Don Markstein has some examples:

Comic book publisher Martin Goodman was no respecter of the property rights of his defunct colleagues. In 1964, he appropriated the name of a superhero published in the '40s by Lev Gleason, and brought out his own version of Daredevil. A couple of years later, he introduced an outright copy of a '50s western character published by Magazine Enterprises, Ghost Rider. It wasn't until late 1967, possibly prompted by a smaller publisher's attempt to do the same, that he finally got around to stealing the name of one of the most prominent comics heroes of all time, Captain Marvel. And this delay was odd, because the name of Goodman's company was (and remains) Marvel Comics."(That would, by the way, be Fawcett's Captain Marvel so what goes around...)

(Fans of fantasy art should find the covers of the old Ghost Rider familiar)

(Fans of fantasy art should find the covers of the old Ghost Rider familiar)

This is how how media companies start. A small music label fills out a CD with a few folk songs. An independent movie company comes up with a low-budget Poe project. An unaffiliated television station runs a late night horror show with public domain films like Little Shop of Horrors and Night of the Living Dead. Then, with the payroll met and some money in the bank, these companies start getting more ambitious.

Expansion of the public domain is creative destruction at its most productive. Not only does it clear the way for new work; it actually provides the building blocks.

Saturday, January 7, 2012

Behavioral Economics for Firms

I wonder if there is a limit to how well firms adhere to economic models> We already have decent evidence that people don't necessarily respond rationally (or else why would they buy Apple shares?). But the executives in the company create a principal agent problem, which may also cause issues at the level of the company itself.

This is not to knock economic models. Epidemiology has many of the same limitations and we have to rely on some pretty challenging assumptions. Rather it is to be careful, with any model, to recall the limitations and exceptions inherent in modeling a complex process.

Friday, January 6, 2012

Astronauts and aquanauts

Fifty years ago, exploring the oceans meant sending down manned bathyspheres and bathyscaphes and establishing undersea habitats like SEALAB and Tektite. Now exploration is done pretty much entirely by tethered robots and remote-controlled submersibles. For other than military purposes, manned deep water vehicles seem to have almost disappeared. Based on a good fifteen minutes on Wikipedia, it appears that serious bathyscaphe-based research ended with the Sixties. (the record for deepest dive has stood since 1960.)

To take the pictures, researchers deployed a tethered robot from their research ship. About the size of a four-wheel-drive truck, the robot was outfitted with an array of high-definition video cameras and still cameras. The researchers would watch a bank of screens of pictures that the robot beamed up from the seabed.

We've all gotten used to the idea of exploring the oceans through a video screen rather than a portal and it's been ages since I've heard anyone talk about colonizing the seas. The cold, hard economic fact is that in extreme environments, machines can do more, and do it more cheaply than humans. That holds for space exploration as well.

It is possible to argue for manned exploration programs but those arguments invariably have to come down to a question, not of science, but of intangibles like what we want to accomplish as a nation. I'm actually sympathetic to these arguments but they have to be made in these terms. This really is something you do not because it's easy but because it's hard.

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

Stock Markets and Beta

This means that historically, the stock market more than doubles your money in real terms every 12 years, but over the last 12 years, it’s down 20%.

That is a great deal of risk to bear as an individual investor. Leaving the market in 1999 and purchasing an annuity (leaving the job market 12 years early) would produce a better retirement than saving for an additional 12 years.

Now add in the losses due to management fees and it can be a tough slog to put together a retirement account. Of course, you can't easily avoid the management fees as taxes are worse than these fees (which mostly seem to be a rather substantial subsidy to wall street). So saving in personal accounts is also hard.

That leaves two possibilities -- a entity that can smooth out risk over decades (e.g. a government) or simply making more income. Since it is not trivial to generate large pay increases, the former does seem like the only realistic way to mitigate time period risk for retirement.

Or am I missing something?

Doing something for non-traditional students

I always felt that the university was not serving these students well, that we should have been finding ways to work around their schedules to make their lives easier and the path to graduation quicker. With that in mind, I liked a lot of what I heard in this NPR report on Western Governors University, a nonprofit online school designed to help adult students finish college.

Shackleford can also keep her costs down by finishing her coursework early. The average time to get a degree at Western Governors is much shorter than at a typical school, where students have to put in a set amount of "seat time."

But the truly unusual thing about this computer-driven system is that it provides a lot of one-on-one attention. Throughout her time at Western Governors, Shackleford will have her own personal student mentor — a combination guidance counselor, career coach and best buddy.

Shackleford has never met her mentor in the flesh, even though she lives about 90 minutes away, just north of Indianapolis. Her name is Stormi Brake, and she also works out of her home office, in a house filled with kids and pets.

When I show up for a visit, Brake is wearing a headset and talking on the phone with one of her 90 students. She is organized and energetic, jumping from student to student to head off any problems. She tracks their progress on a computer dashboard the school uses. She shows me that students who are completing required tasks on schedule show up in green, while those who are behind show up in red, a sign that the mentor needs to get in touch.

Brake has a strong background in science and teaching, but her job is to make sure her students get their degree. Students with questions about course content can turn to another kind of mentor — a course mentor — who's considered an expert on the subject.

Monday, January 2, 2012

Cash for Citations

An astronomer at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, was offering him a contract for an adjunct professorship that would pay $72,000 a year. Kirshner, an astrophysicist at Harvard University, would be expected to supervise a research group at KAU and spend a week or two a year on KAU’s campus, but that requirement was flexible, the person making the offer wrote in the e-mail.

I am actually not sure that this rises to the level of a "scam" by modern standards. The professor would, after all, work with the students at KAU and be residential for at least part of the year. Sure, the salary is a bit high for two weeks worth of work but access to a top researcher can be worth a lot if he contributed remotely. To rise to the level of an actual scam, the flexible requirement would have to be negotiable to no duties.

Now, the concern is that the astronomer would have to list the KAU affiliation on all of their papers. On the other hand, if they are a salaried adjunct professor then that would actually be pretty normal. Several of my colleagues have positions cobbled together from multiple places and the requisite need to list multiple affiliations.

The real issue is the ability of universities to purchase reputations. It has long been true that extremely gifted and creative researchers have better employment options at least partially because of the prestige they bring to the hiring institution. In a world with flexible work locations (consider MITx), these issues are likely to become larger over time.

But the idea of "cash for citations" is really a salary for research productivity. The real question is how residential does a professor need to be to count as affiliated.