Austerians don’t get off on other people’s suffering. They, for the most part, honestly believe that theirs is the quickest way through the suffering. They may be right or they may be wrong. When Krugman says he’s only worried about “premature” fiscal discipline, it becomes largely a question of emphasis anyway. But the austerians deserve credit: They at least are talking about the spinach, while the Krugmanites are only talking about dessert.To get a feel for just how odd this analogy is, you need to remember that a large part of this 'spinach' is saying no to people who want to borrow money almost interest-free and spend it on infrastructure, education and research thus avoiding far greater costs in the future.

These are all urgent issues but the infrastructure crisis in particular demands immediate action. Civil engineers have been ringing this alarm bell for years:

Back in March, when the American Society of Civil Engineers issued an infrastructure report card for the entire country, its very best grade — a B-minus — went to solid-waste disposal. Thanks to our decent progress in recycling, the United States’ overall grade-point average in subjects ranging from aviation to water systems actually ticked up from the previous GPA.Those warnings became considerably less abstract yesterday:

To a pitiful 1.30, that is, on a 4.00 scale.

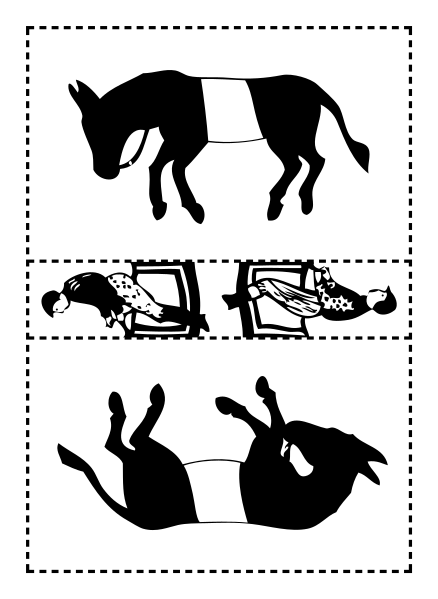

SEATTLE — A large section of a bridge on Interstate 5 north of Seattle collapsed Thursday evening, sending vehicles and people plunging into the swirling, frigid waters of the Skagit River."Without warning" here is a bit of a relative term:

Three people were hospitalized in stable condition, officials said. No one was killed.

The bridge failed without warning between the towns of Burlington and Mount Vernon on the major route linking Seattle with the Canadian border, the Washington State Patrol said.

The 58-year-old bridge in Washington, a crucial link to the Canadian border traveled heavily by trucks, was inspected every two years, most recently in November, state Department of Transportation spokesman Bart Treece told the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s an old bridge. We have to look into the specifics. We do have a lot of old, aging structures, and a lot of them hold up really well,” he said.

The National Bridge Inventory lists the bridge as “functionally obsolete,” with “somewhat better than minimum adequacy to tolerate being left in place as is.” It received a sufficiency rating of 57.4 out of 100.

Putting aside for the moment the question of public safety, the economic impact of bad infrastructure can be huge (from the same story):

Washington’s main north-south thoroughfare, though, was likely to remain closed 60 miles north of Seattle for an indefinite period, state officials warned. The nearly 71,000 vehicles a day that travel the bridge between Mt. Vernon and Burlington were diverted through city streets to another nearby bridge.Just to be clear:

dessert = making repairs now

spinach = deferring repairs now and making more costly ones later when interest rates will be higher

Kinsley's analogies are like America's bridges; they need a lot of work.