From Just a Pile of Old Comics.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Saturday, May 25, 2013

Weekend blogging -- Uncle Art's Funland

Art Nugent doesn't have the mathematical following that Dudney or Loyd (he seldom hit the depths of those two), but he was a pretty good puzzle maker and a damned fine cartoonist and his output was extraordinary. For more than forty years he put out newspaper features and comics pages filled with puzzles, games, riddles, activities and magic tricks.

From Just a Pile of Old Comics.

From Just a Pile of Old Comics.

Friday, May 24, 2013

Spinach is supposed to make you stronger -- Infrastructure and the Kinsley/Krugman fight

Virtually everyone who reads this blog has heard about (and is probably sick of hearing about) Michael Kinsley's contrarian defense of austerians that ended with this analogy:

These are all urgent issues but the infrastructure crisis in particular demands immediate action. Civil engineers have been ringing this alarm bell for years:

Putting aside for the moment the question of public safety, the economic impact of bad infrastructure can be huge (from the same story):

dessert = making repairs now

spinach = deferring repairs now and making more costly ones later when interest rates will be higher

Kinsley's analogies are like America's bridges; they need a lot of work.

Austerians don’t get off on other people’s suffering. They, for the most part, honestly believe that theirs is the quickest way through the suffering. They may be right or they may be wrong. When Krugman says he’s only worried about “premature” fiscal discipline, it becomes largely a question of emphasis anyway. But the austerians deserve credit: They at least are talking about the spinach, while the Krugmanites are only talking about dessert.To get a feel for just how odd this analogy is, you need to remember that a large part of this 'spinach' is saying no to people who want to borrow money almost interest-free and spend it on infrastructure, education and research thus avoiding far greater costs in the future.

These are all urgent issues but the infrastructure crisis in particular demands immediate action. Civil engineers have been ringing this alarm bell for years:

Back in March, when the American Society of Civil Engineers issued an infrastructure report card for the entire country, its very best grade — a B-minus — went to solid-waste disposal. Thanks to our decent progress in recycling, the United States’ overall grade-point average in subjects ranging from aviation to water systems actually ticked up from the previous GPA.Those warnings became considerably less abstract yesterday:

To a pitiful 1.30, that is, on a 4.00 scale.

SEATTLE — A large section of a bridge on Interstate 5 north of Seattle collapsed Thursday evening, sending vehicles and people plunging into the swirling, frigid waters of the Skagit River."Without warning" here is a bit of a relative term:

Three people were hospitalized in stable condition, officials said. No one was killed.

The bridge failed without warning between the towns of Burlington and Mount Vernon on the major route linking Seattle with the Canadian border, the Washington State Patrol said.

The 58-year-old bridge in Washington, a crucial link to the Canadian border traveled heavily by trucks, was inspected every two years, most recently in November, state Department of Transportation spokesman Bart Treece told the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s an old bridge. We have to look into the specifics. We do have a lot of old, aging structures, and a lot of them hold up really well,” he said.

The National Bridge Inventory lists the bridge as “functionally obsolete,” with “somewhat better than minimum adequacy to tolerate being left in place as is.” It received a sufficiency rating of 57.4 out of 100.

Putting aside for the moment the question of public safety, the economic impact of bad infrastructure can be huge (from the same story):

Washington’s main north-south thoroughfare, though, was likely to remain closed 60 miles north of Seattle for an indefinite period, state officials warned. The nearly 71,000 vehicles a day that travel the bridge between Mt. Vernon and Burlington were diverted through city streets to another nearby bridge.Just to be clear:

dessert = making repairs now

spinach = deferring repairs now and making more costly ones later when interest rates will be higher

Kinsley's analogies are like America's bridges; they need a lot of work.

Notes on an unwritten paper -- Naive Bayesian Classifiers and Order of Composition

[Update: I've got some more thoughts on Gutenberg-based research in my latest post.]

I'm planning on writing some posts on the potential of and the potential concerns about open data (possibly even getting Joseph to join in) so I thought I'd dust off a somewhat relevant idea I had a few years back. If anyone wants to see if they can get something publishable out of this, feel free. In the meantime, I plan on getting some mileage out of it as an example.

A few years ago, I wrote some code for text mining. It was really basic, standard stuff -- using naive Bayesian classifiers and n-grams (normally techniques for assigning authorship) -- but it worked well and was fun to play around with. I used various books from Project Gutenberg as test data and selected authors with styles and backgrounds ranging from close (Dickens and Trollope) to out there (Thorstein Veblen) with a translation of Verne as someone neutral. The two Victorians also had the advantage of having written lots of books over many years.

The idea was to approach this less as a classification problem and more of a question of distance between points in a literary space. Here the "likelihood score" was more a measure of similarity. As you would expect, Great Expectations was more similar to Nicholas Nickleby than to Barchester Towers, more similar to Barchester Towers than to a translated Master of the World and more similar to Master of the World than to Theory of the Leisure Class. It also worked as expected when you compared works of the same author written at different points in his career: Great Expectations (1860 to 1861) was more similar to Our Mutual Friend (1864 to 1865) than to Nicholas Nickleby (1838 to 1839).

Obviously this was a tiny trial run, but it did suggest that there's something out there, as did a recent literature search which turned up at least one related paper from 2011 ("Predicting the Date of Authorship of Historical Texts" by A. Tausz) which used NBCs to determine absolute rather than relative dates. Still even with Tausz' paper (which is very interesting, by the way) there still should be room for research into intra-author questions and, more importantly, into lots of other questions using data from project Gutenberg.

And on top of that you can apparently find interesting stuff to read at the site as well.

I'm planning on writing some posts on the potential of and the potential concerns about open data (possibly even getting Joseph to join in) so I thought I'd dust off a somewhat relevant idea I had a few years back. If anyone wants to see if they can get something publishable out of this, feel free. In the meantime, I plan on getting some mileage out of it as an example.

A few years ago, I wrote some code for text mining. It was really basic, standard stuff -- using naive Bayesian classifiers and n-grams (normally techniques for assigning authorship) -- but it worked well and was fun to play around with. I used various books from Project Gutenberg as test data and selected authors with styles and backgrounds ranging from close (Dickens and Trollope) to out there (Thorstein Veblen) with a translation of Verne as someone neutral. The two Victorians also had the advantage of having written lots of books over many years.

The idea was to approach this less as a classification problem and more of a question of distance between points in a literary space. Here the "likelihood score" was more a measure of similarity. As you would expect, Great Expectations was more similar to Nicholas Nickleby than to Barchester Towers, more similar to Barchester Towers than to a translated Master of the World and more similar to Master of the World than to Theory of the Leisure Class. It also worked as expected when you compared works of the same author written at different points in his career: Great Expectations (1860 to 1861) was more similar to Our Mutual Friend (1864 to 1865) than to Nicholas Nickleby (1838 to 1839).

Obviously this was a tiny trial run, but it did suggest that there's something out there, as did a recent literature search which turned up at least one related paper from 2011 ("Predicting the Date of Authorship of Historical Texts" by A. Tausz) which used NBCs to determine absolute rather than relative dates. Still even with Tausz' paper (which is very interesting, by the way) there still should be room for research into intra-author questions and, more importantly, into lots of other questions using data from project Gutenberg.

And on top of that you can apparently find interesting stuff to read at the site as well.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Scandal, metareporting and the dumber-reader theory

Everybody has heard of the greater fool theory of investing where you buy a stock not because you think its assets are undervalued or because there's a good chance that the company will make money but because you believe there is someone out there who will pay significantly more than you paid.

I've noticed a somewhat analogous trend in journalism today, particularly involving the coverage 'scandals.' I apologize for the quotes but they're there for a reason I'll get to in a bit. In the traditional model of reporting, the journalist implicitly claims that the information being reported is accurate, representative and significant enough to justify the readers' time.

Over the past few years, though, journalists seem to have gotten more likely to downplay these traditional elements (what we might call the fundamental value of the story) and focus on what the impact of the story will be if people other than the reader believe it (the dumber-reader theory). In generic form, the stories go something like this: "A made accusations against B. There is no reason to believe these accusations but if they gain traction, they could hurt B."

Perhaps the most dramatic example of the past few years was swiftboating where most of the attention was paid to how Kerry's handling of the charges would affect his campaign while relatively little was given to the charges' validity (a question that in previous times would probably have been considered a necessary condition for the story to advance).

Don't get me wrong. Coverage has always included questions about the impact of scandals, but it seems like the process before had more of a tree structure: ask question A and then, based on the answer, ask either question B or C. I'm not saying that this rose to the level of hard and fast rule, just that it was the norm. First you asked if an accusation was true. If the answer was yes you asked how serious was the offense; if the answer was no you asked if the accuser had been deliberately misleading. And so on...

I can see how moving away from that structure is a good thing for journalists. For the rest of us, however, it does not look like a good thing at all.

I've noticed a somewhat analogous trend in journalism today, particularly involving the coverage 'scandals.' I apologize for the quotes but they're there for a reason I'll get to in a bit. In the traditional model of reporting, the journalist implicitly claims that the information being reported is accurate, representative and significant enough to justify the readers' time.

Over the past few years, though, journalists seem to have gotten more likely to downplay these traditional elements (what we might call the fundamental value of the story) and focus on what the impact of the story will be if people other than the reader believe it (the dumber-reader theory). In generic form, the stories go something like this: "A made accusations against B. There is no reason to believe these accusations but if they gain traction, they could hurt B."

Perhaps the most dramatic example of the past few years was swiftboating where most of the attention was paid to how Kerry's handling of the charges would affect his campaign while relatively little was given to the charges' validity (a question that in previous times would probably have been considered a necessary condition for the story to advance).

Don't get me wrong. Coverage has always included questions about the impact of scandals, but it seems like the process before had more of a tree structure: ask question A and then, based on the answer, ask either question B or C. I'm not saying that this rose to the level of hard and fast rule, just that it was the norm. First you asked if an accusation was true. If the answer was yes you asked how serious was the offense; if the answer was no you asked if the accuser had been deliberately misleading. And so on...

I can see how moving away from that structure is a good thing for journalists. For the rest of us, however, it does not look like a good thing at all.

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

Pets

Frances Woolley:

Really what we want to maximize is high quality life. In cases where high quality and life contradict each other then one has to choose (and it is never an easy decision). So it is not surprising that people adopt pets that they are compatible with. But just ask a dog owner what they will do to extend the life of a sick Labrador Retriever and you might be surprised . . .

So which preference is dominant? The breed decision or the attempt to prolong the life of one's furry friend?

Indeed, when a person selects a pet, life expectancy is one of the last things considered (see, for example, this pet selection guide, or this one or this one). Instead, "experts" recommend choosing a pet who will be a good match for his or her owner in terms of activity level, sociability, and so on. Good health matters - sensible owners avoid breeds prone to health problems. But not life expectancy per se.I think there is a good point here -- life expectancy is not the only good that people are interested in. Sure, I do not want to die young. But if terrible quality of life was the only way to extend one's life span that would seem sub-optimal too.

Really what we want to maximize is high quality life. In cases where high quality and life contradict each other then one has to choose (and it is never an easy decision). So it is not surprising that people adopt pets that they are compatible with. But just ask a dog owner what they will do to extend the life of a sick Labrador Retriever and you might be surprised . . .

So which preference is dominant? The breed decision or the attempt to prolong the life of one's furry friend?

Un-self-awareness at the New Republic -- more Rhee-views

Michele Rhee has popped up in a couple of notable posts this week.

First Nicholas Lemann writing in TNR:

It is, of course, difficult to pivot gracefully so it's not surprising to see an awkward turn or two here. Most memorable is the description of Rhee's stated view of politics as "un-self-aware." Not only is the term itself good for a chuckle, but by this criterion Rhee's un-self-awareness would apply to the vast majority of politicians (think of all the times you've heard candidate express a similar scorn). It is the most standard of standard campaign lies, made all the more transparent by Rhee's relentless and ruthless political maneuvers (including reaching her current position by climbing over the still-warm corpse of Adrian Fenty's career).

The press is slowly coming to terms with how badly it was played by Rhee, but they are getting there. The question now is how will the fall of one reformer affect the movement? Andrew Gelman sees this as indicative of something bigger.

1. Given the ugly nature of the data (confounded, nested, etc.) we would not get anything usable out of the two or three years of data window we would have to evaluate a teacher;

2. The test might give us an inaccurate or incomplete picture of what students were learning;

3. The system would be vulnerable to cheaters;

4. The tests would distort education priorities.

Rhee's crash drives home 3 but I don't know that it says that much about the rest which is troublesome because those are the ones that bother me more.

First Nicholas Lemann writing in TNR:

Rhee is not one for exquisite sensitivity. She closed schools, fired teachers, and (though she assures us that “I had never sought the limelight”) became famous. She was on the covers of Time (holding a broom) and Newsweek, and was one of the stars of Waiting for Superman. It is usually a fundamental rule of politics that a department head isn’t supposed to do anything to make her boss unpopular or to upstage him. Rhee did not follow this rule. She has a special scorn for “politics” and often praises Fenty for not considering it when making decisions, but this is both un-self-aware (Rhee’s policies were very good politics in white Washington) and impractical. We live in a democracy, so officials have to contend with public opinion and with groups organized to promote their own interests. Many American politicians over the last generation, including all of the last five presidents, have been able to push education policies in the same realm as Rhee’s in a way that kept their coalitions together. That is what Rhee and Fenty were unusually bad at doing, and Rhee’s insistence that “politics” is a terrible thing that only her opponents practice was surely a big part of the reason why.Lemann represents the pivot phase of the press's relationship with Rhee, not quite ready to address painful topics, but moving away from the hagiography that until recently marked much of Rhee's coverage (particularly at the New Republic).

It is, of course, difficult to pivot gracefully so it's not surprising to see an awkward turn or two here. Most memorable is the description of Rhee's stated view of politics as "un-self-aware." Not only is the term itself good for a chuckle, but by this criterion Rhee's un-self-awareness would apply to the vast majority of politicians (think of all the times you've heard candidate express a similar scorn). It is the most standard of standard campaign lies, made all the more transparent by Rhee's relentless and ruthless political maneuvers (including reaching her current position by climbing over the still-warm corpse of Adrian Fenty's career).

The press is slowly coming to terms with how badly it was played by Rhee, but they are getting there. The question now is how will the fall of one reformer affect the movement? Andrew Gelman sees this as indicative of something bigger.

My impression is that there has been a shift. A few years ago, value-added assessment etc was considered the technocratic way to go, with opponents being a bunch of Luddite dead-enders. Now, though, the whole system is falling apart. We can learn a lot from tests, no doubt about that, but there’s a lot less sense that they should be used to directly evaluate teachers. We’ve moved to a more modern, quality-control perspective in which the goal is to learn and improve the system, not to reward or punish individual workers.I'm not so sure. From the beginning there have been at least four major concerns:

This shift may have not happened yet at the political level, but it’s my sense that this is the direction that things are going. The Rhee story is symbolic of the fallacies of measurement.

1. Given the ugly nature of the data (confounded, nested, etc.) we would not get anything usable out of the two or three years of data window we would have to evaluate a teacher;

2. The test might give us an inaccurate or incomplete picture of what students were learning;

3. The system would be vulnerable to cheaters;

4. The tests would distort education priorities.

Rhee's crash drives home 3 but I don't know that it says that much about the rest which is troublesome because those are the ones that bother me more.

A smart post from Felix Salmon

Felix Salmon:

But the second point is also really salient -- it is often amazing how much we overlook the subsidization of activities are social norms. We don't see the use of roads for cars and not bicycles as a subsidization of the car. Heck, I am often annoyed by bicyclists who can't decide what set of rules they are following (when they switch back and forth between being a fellow vehicle and a pedestrian it makes me nervous as I have a life-long goal to never hit a cyclist). But the roads could just as easily be claimed by walkers, horses, bicycles and so forth in a much easier form of mixed use.

My point here is that technology has a tendency to create its own norms. The classic example is the automobile — a technology which kills more than 30,000 Americans every year. From the 1930s through the 1990s, societal norms about who roads belonged to, and what people should do on them, were turned on their head thanks to the new technology. The dangerous new activity allowed by the new technology became the privileged norm, to the point at which just about all other road-based activity — and roads have been around for thousands of years, remember, since long before the automobile — essentially ceased to exist. Eventually, we reached the point at which elected representatives were happy saying that if a bicyclist gets killed by a car, it’s the bicyclist’s fault for being on the road in the first place.I think that this is a very interesting point at two levels. One, is that it does point out that society can change around innovation just as much as innovation can change society. I think that this will be broadly applicable to innovations like driverless cars that are legal nightmares now, but could easy become the standard with enough adoption. It's never clear when a technology will win this sort of breakthrough success (the innovation grave-yard is full of such examples). But it does point out that some classes of argument are less likely to succeed.

But the second point is also really salient -- it is often amazing how much we overlook the subsidization of activities are social norms. We don't see the use of roads for cars and not bicycles as a subsidization of the car. Heck, I am often annoyed by bicyclists who can't decide what set of rules they are following (when they switch back and forth between being a fellow vehicle and a pedestrian it makes me nervous as I have a life-long goal to never hit a cyclist). But the roads could just as easily be claimed by walkers, horses, bicycles and so forth in a much easier form of mixed use.

Monday, May 20, 2013

Maybe he meant the toolbox of some economists...

Greg Mankiw has a piece up at the New York Times that opens with this assertion: "Nothing in the toolbox of economists makes us good stock pickers."

The article does a good job explaining the relevant economics concepts to a lay audience (as expected given the author), but I did notice a slight but amusing omission from this:

The article does a good job explaining the relevant economics concepts to a lay audience (as expected given the author), but I did notice a slight but amusing omission from this:

Advocates of market rationality now say that stock prices move in response to changing risk premiums, though they can’t explain why risk premiums move as they do. Others suggest that the market moves in response to irrational waves of optimism and pessimism, what John Maynard Keynes called the “animal spirits” of investors. Either approach is really just an admission of economists’ ignorance about what moves the market.I'm not entirely sure Keynes would have conceded that point:

Keynes was ultimately a successful investor, building up a private fortune. His assets were nearly wiped out following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which he did not foresee, but he soon recouped. At Keynes's death, in 1946, his worth stood just short of £500,000 – equivalent to about £11 million ($16.5 million) in 2009. The sum had been amassed despite lavish support for various causes and his personal ethic which made him reluctant to sell on a falling market when if too many did it could deepen a slump.[135]Just imagine how much Keynes would have socked away if he didn't have that live-for-today attitude.

Sunday, May 19, 2013

Weekend Blogging -- Puzzles! Puzzles! Puzzles! (from our side of the pond)

Having just done Dudney, it's only fair that we give equal time to America's turn of the century puzzle master, Sam Loyd.

If the name is new to you, here's a quick introduction from Wikipedia:

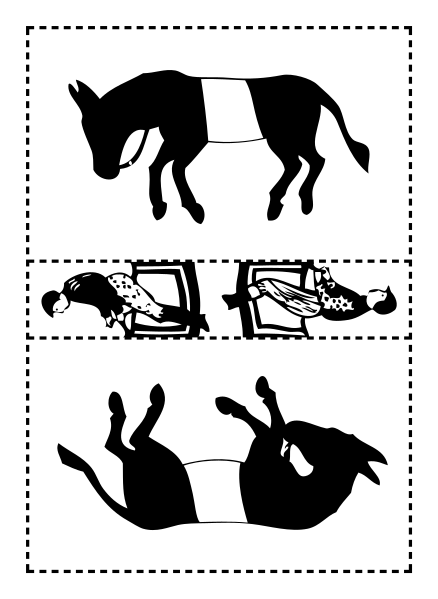

Loyd was a master of all sorts of mathematical diversions but he is best remembered for his geometric puzzles. Perhaps the best known of these were the "Trick Donkeys." The object is to cut this picture into the three pieces indicated and rearrange them so that the jockeys appear to be riding the donkeys. No tearing or folding allowed and the donkeys cannot overlap.

One of the interesting things about this puzzle is that there are relatively few ways of arranging the pieces but people trying to solve the puzzle will almost invariably keep retrying the same unsuccessful arrangements.

Another famous puzzle (and one I'd like to revisit if I have the time) is Back from the Klondike:

From Wikipedia:

Here are some sample pages including the yellow-menace puzzle, Get Off the Earth. Solutions are found in the links that follow each page.

http://www.mathpuzzle.com/loyd/cop340-341.html

http://www.mathpuzzle.com/loyd/cop362-363.html

If the name is new to you, here's a quick introduction from Wikipedia:

Loyd is widely acknowledged as one of America's great puzzle-writers and popularizers, often mentioned as the greatest—Martin Gardner called him "America's greatest puzzler", and The Strand in 1898 dubbed him "the prince of puzzlers". As a chess problemist, his composing style is distinguished by wit and humour.[For an in depth look at both Dudney and Loyd, Gardner is the go-to guy.]

However, he is also known for lies and self-promotion, and criticized on these grounds—Martin Gardner's assessment continues "but also obviously a hustler", Canadian puzzler Mel Stover called Loyd "an old reprobate", and Matthew Costello calls him both "puzzledom's greatest celebrity...popularizer, genius," but also "huckster...and fast-talking snake oil salesman."[4] He collaborated with puzzler Henry Dudeney for a while, but Dudeny broke off the correspondence and accused Loyd of stealing his puzzles and publishing them under his own name. Dudeney despised Loyd so intensely he equated him with the Devil.[5]

Loyd was a master of all sorts of mathematical diversions but he is best remembered for his geometric puzzles. Perhaps the best known of these were the "Trick Donkeys." The object is to cut this picture into the three pieces indicated and rearrange them so that the jockeys appear to be riding the donkeys. No tearing or folding allowed and the donkeys cannot overlap.

One of the interesting things about this puzzle is that there are relatively few ways of arranging the pieces but people trying to solve the puzzle will almost invariably keep retrying the same unsuccessful arrangements.

Another famous puzzle (and one I'd like to revisit if I have the time) is Back from the Klondike:

From Wikipedia:

Back from the Klondike is one of Sam Loyd's most famous puzzles, first printed in the New York Journal and Advertiser on April 24, 1898. In introducing the puzzle, Loyd describes it as having been constructed to specifically foil Leonhard Euler's rule for solving any maze puzzle by working backwards from the end point.[1]

The following are Sam Loyd's original instructions:

Start from the heart in the center. Go three steps in a straight line in any one of the eight directions, north, south, east, west, northeast, northwest, southeast, or southwest. When you have gone three steps in a straight line you will reach a square with a number on it, which indicates the second day's journey, as many steps as it tells, in a straight line in any one of the eight directions. From this new point, march on again according to the number indicated, and continue on in this manner until you come upon a square with a number which will carry you just one step beyond the border, thus solving the puzzle.

Over at the Mathematical Association of America site. Ed Pegg Jr. has put Loyd's magnum opus, Sam Loyd's Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles, Tricks, and Conundrums online.

http://www.mathpuzzle.com/loyd/cop340-341.html

http://www.mathpuzzle.com/loyd/cop362-363.html

Saturday, May 18, 2013

At last a candidate Maureen Dowd can support

Jonathan Chait has a good column about President Obama's recent comments about "going Bulworth," an allusion to the 1998 Warren Beatty movie about a politician who as a result of a drunken but honest rant finds his career reinvigorated.

Not surprisingly, this notion holds a special appeal for Maureen Dowd.

[and in case you're wondering, the sketch preceded the movie]

The trouble is that these [frank] answers, while true, don’t actually help Obama. Any political scientist will tell you that the scope for possible legislation in this term is very narrow: The median House member is a very conservative Republican who represents a district that voted for Mitt Romney, and whose biggest political risk is losing a primary to an even more conservative Republican.Bulworth is variant of the "straight-talking everyman takes control from the politicians" genre. Bulworth starts out as a standard politician then becomes a straightshooter, but the underlying fantasy is basically the same as that of Dave and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: a political savior who would cut through the corruption and needless complexity with plain talk and common sense.

But most political reporters and analysts don’t pay attention to the political science. They like narratives that revolve around the president as a protagonist. When you confront them with structural analysis that confounds their narratives, they just get upset with you. It serves no purpose. That’s why I advised Obama to use “less real talk and more bullshit.”

A post-presidency Obama who actually spoke his mind, rather than fashion himself a post-partisan eminence, as post-presidents do — now that would be awesome. But the reason politicians don’t go Bulworth is that it doesn’t work. The truth about legislative dynamics is complicated and depressing. People don’t want to hear it.

Last night, for example, Obama said of the IRS scandal, “The good news is it’s fixable, and it’s in everyone’s best interest to work together to fix it.” That is some prime-caliber bullshit. Of course it’s not in the Republicans’ best interest to fix the problems with IRS enforcement. It’s in their interest to prevent any fix and let the problems linger as long as possible.

But if he had said that, there would have been a huge outcry, and probably a presidential apology. Nobody objected to Obama’s faux-naïve claim that Republicans will naturally want to solve the problem. Bullshit works. Bulworth doesn’t.

Not surprisingly, this notion holds a special appeal for Maureen Dowd.

Mr. Obama’s errors on the helter-skelter stimulus package were also self-induced. He should put down those Lincoln books and order “Dave” from Netflix.But if we're going to go down this road, why not take it to its logical extreme?

When Kevin Kline becomes an accidental president, he summons his personal accountant, Murray Blum, to the White House to cut millions in silly programs out of the federal budget so he can give money to the homeless.

“Who does these books?” Blum says with disgust, red-penciling an ad campaign to boost consumers’ confidence in cars they’d already bought. “If I ran my office this way, I’d be out of business.”

[and in case you're wondering, the sketch preceded the movie]

Friday, May 17, 2013

"America’s Most Profitable Products"

I always worry about the methodology when I see one of these lists, but with that caveat, I still found this interesting. What especially caught my eye was how much brand drives the success of these products. Apple charges a significant premium for the logo, but it's the next three that really demonstrate the value of marketing.

With Apple, it's difficult to say how much success can be attributed to brand and how much is due to superior quality (they do make good stuff) and patents. With Marlboro, Monster and Coke, numerous comparable, even indistinguishable products are available at a significantly lower price.

Brand is the philosopher's stone of business. No one knows exactly how it works (and those who claim otherwise are not to be trusted), but there are people who are good at it and for those who are good and very lucky, the pay-off is amazing.

With Apple, it's difficult to say how much success can be attributed to brand and how much is due to superior quality (they do make good stuff) and patents. With Marlboro, Monster and Coke, numerous comparable, even indistinguishable products are available at a significantly lower price.

Brand is the philosopher's stone of business. No one knows exactly how it works (and those who claim otherwise are not to be trusted), but there are people who are good at it and for those who are good and very lucky, the pay-off is amazing.

1. iPhone

Operating margin: 40%

Revenue: $80.5 billion

Market share: 20.9%

Industry: Computer hardware

2. Marlboro

Operating margin: 30%

Revenue: $19.0 billion

Market share: 42.6%

Industry: Tobacco

3. Monster

Operating margin: 26.7%

Revenue: $1.9 billion

Market share: 37.2%

Industry: Soft drinks

4. Coca-Cola

Operating margin: 25%

Revenue: $14.3 billion

Market share: 41.9%

Industry: Soft drinks

5. Enfamil

Operating margin: 24%

Revenue: $2.3 billion

Market share: 15.1%

Industry: Packaged foods and meats

6. Folgers

Operating margin: 23.6%

Revenue: $2.3 billion

Market share: 11.8% (U.S.)

Industry: Packaged foods and meats

7. Garmin nüvi

Operating margin: 15%

Revenue: $1.2 billion

Market share: Greater than 50%

Industry: Consumer electronics

Affinity cons and the looting phase in education

Affinity cons work in large part because when people see someone with similar background and cultural signifiers, they assume other similarities: common goals, values, approaches.

Movement reformers, particularly those who came in through Teach for America (and that's something you see a lot) often get sucked in by something similar. They look at someone like Michelle Rhee and the rhetoric and the resume feel familiar. They see something they recognize in the upper-middle class upbringing (including private schools for junior high and high school), the Ivy League education, the TfA stint in a poor urban school. Lots of leaders in education today have that exact same bio and since the vast majority of them genuinely care about kids, they assume Rhee does as well.

Viewed without the affinity bias, however, Rhee's record mainly shows a pattern of intense self promotion, often the expense of students:

She appears to have started her career by greatly overstating test score improvements during her Teach for America days;

As an administrator, she was charged with abusing her authority to political ends:

and covering up a major cheating scandal;

She lent her political capital to anti-labor measures only tangentially related to education (but vital to her allies);

She oversaw the creation of a convoluted metric that assigned the top ranks to schools she and her allies were responsible for (despite those schools' terrible performance on the very metrics Rhee had previously championed);

And she endorsed a Bobby Jindal initiative which pretty much guaranteed wide-spread fraud.

From Vickie Welborn and Mary Nash-Wood (via Charles Pierce):

Movement reformers, particularly those who came in through Teach for America (and that's something you see a lot) often get sucked in by something similar. They look at someone like Michelle Rhee and the rhetoric and the resume feel familiar. They see something they recognize in the upper-middle class upbringing (including private schools for junior high and high school), the Ivy League education, the TfA stint in a poor urban school. Lots of leaders in education today have that exact same bio and since the vast majority of them genuinely care about kids, they assume Rhee does as well.

Viewed without the affinity bias, however, Rhee's record mainly shows a pattern of intense self promotion, often the expense of students:

She appears to have started her career by greatly overstating test score improvements during her Teach for America days;

As an administrator, she was charged with abusing her authority to political ends:

and covering up a major cheating scandal;

She lent her political capital to anti-labor measures only tangentially related to education (but vital to her allies);

She oversaw the creation of a convoluted metric that assigned the top ranks to schools she and her allies were responsible for (despite those schools' terrible performance on the very metrics Rhee had previously championed);

And she endorsed a Bobby Jindal initiative which pretty much guaranteed wide-spread fraud.

From Vickie Welborn and Mary Nash-Wood (via Charles Pierce):

Southwood High School junior Randall Gunn is a straight-A student.[Update: the story continues here]

So when the school’s principal saw his name come up as registering to retake several courses online, it immediately raised a red flag. Gunn was called into a counselor’s office and told he was enrolled in three Course Choice classes — all of which he already had passed standardized tests with exceptional scores.

“I had no clue what was going on,” Gunn said. “I have no reason to take these classes and still don’t know who signed me up.”

More than 1,100 Caddo and Webster students have signed up to participate in what some say are questionable Course Choice programs. According to parents, students, and Webster and Caddo education officials, FastPath Learning is signing up some students it shouldn’t — in many cases without parent or student knowledge.

A free tablet computer is offered to those who enroll, and some educators believe that’s all the potential enrollees hear. Money to pay for the courses comes from each school district’s state-provided Minimum Foundation Program funding.

Half of the money — courses range from $700 to $1,275 each — must be paid to FastPath and other providers up front. Neither students nor their parents are responsible for the tablet devices if they are lost or stolen. And they can keep them even if they don’t pass the course.

“This all goes back to all of the education reforms that were passed within eight days during last year’s session. This is what you get,” state Rep. Gene Reynolds, D-Dubberly, said of the apparent lack of oversight. “I’m not saying the idea was bad, but they are not doing it the way it should be done.”

Thursday, May 16, 2013

What the Zuck is wrong NBC?

Despite the title, this isn't a joke. NBC raises all sorts of interesting questions about why some massive companies have long periods of excellence and others have runs of incompetence, or more specifically a period of excellence followed immediately by a period of gross incompetence (one that shows no sign of abating).

Here's Ken Levine (who knows what he's talking about on the subject) assessing the current state of the network:

The second period starts in the early Eighties and is usually associated with Grant Tinker and Brandon Tartikoff. This was the era of Must-see TV. NBC went from last to first and remained arguably the dominant network for almost twenty years.

Sometime around 2000, we hit the third period. The network went into sharp decline and has mostly stayed at the bottom ever since.

The standard explanation for this is good management/bad management (I've used it myself), but I'm starting to have my doubts. For starters, that relies on both great-man and idiot-in-charge theories and though I find the second somewhat more believable than the first (it is almost always easier to screw up something good than it is to fix something bad), both tend to have their impact exaggerated.

Worse yet, if we extend the data in either direction -- pre-Tinker (i.e. Silverman, who had a long string of successes stretching over two networks before he got to NBC) and post-Zucker -- the theory ceases to hold. We can possibly explain away the Silverman era based on timing, short tenure and expectations (Silverman's run was less of a disaster than most people realize and on some ways even laid the groundwork for Tinker's success*).

The post-Zucker era, however, is not easily explained away. Zucker was an embarrassingly underqualified executive who oversaw what was probably the worst decline in more than six decades of network television, but he has been gone for almost three years and there does not seem to have been a noticeable improvement or even a significant change in direction.

NBC remains an organization that has no clue about how to do its job: it doesn't know how to develop or cultivate shows; it decided to waste a large chunk of its valuable Olympics real estate promoting arguably the least promising new show it had at the time; developing a new channel for the terrestrial market, it launches one of the most badly thought out ad campaigns you'll ever see and makes programming decisions like pairing Munster, Go Home with a drama about a raped nun killing her newborn baby.

I don't have an explanation for what happened with NBC. I don't even have a good theory. I do however have a different way of framing the question. Instead of focusing on the styles and decisions of different executives, perhaps we should be asking how a company goes from hiring executives like Tinker and Tartikoff to hiring executives like Zucker and apparently many more like him.

* From Wikipedia:

Here's Ken Levine (who knows what he's talking about on the subject) assessing the current state of the network:

But the message is clear. NBC was a disaster last year. It’s hard to build an audience with so many new shows but what choice did they have? Last year they had star vehicles (like Matthew Perry in GO ON), the Olympics to promote their schedule, THE VOICE, and SUNDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL. And still they finished the year in shambles.This is what might be called the third period of NBC television (when we go back to the radio era, things get complicated, with what was NBC being split into NBC and ABC, but that's a story for another time). For about the first thirty years, CBS was on top, NBC was in the middle and ABC was at the bottom. In the late Seventies, though, everything went topsy turvy. ABC hit number one and actually started poaching stations from NBC.

The second period starts in the early Eighties and is usually associated with Grant Tinker and Brandon Tartikoff. This was the era of Must-see TV. NBC went from last to first and remained arguably the dominant network for almost twenty years.

Sometime around 2000, we hit the third period. The network went into sharp decline and has mostly stayed at the bottom ever since.

The standard explanation for this is good management/bad management (I've used it myself), but I'm starting to have my doubts. For starters, that relies on both great-man and idiot-in-charge theories and though I find the second somewhat more believable than the first (it is almost always easier to screw up something good than it is to fix something bad), both tend to have their impact exaggerated.

Worse yet, if we extend the data in either direction -- pre-Tinker (i.e. Silverman, who had a long string of successes stretching over two networks before he got to NBC) and post-Zucker -- the theory ceases to hold. We can possibly explain away the Silverman era based on timing, short tenure and expectations (Silverman's run was less of a disaster than most people realize and on some ways even laid the groundwork for Tinker's success*).

The post-Zucker era, however, is not easily explained away. Zucker was an embarrassingly underqualified executive who oversaw what was probably the worst decline in more than six decades of network television, but he has been gone for almost three years and there does not seem to have been a noticeable improvement or even a significant change in direction.

NBC remains an organization that has no clue about how to do its job: it doesn't know how to develop or cultivate shows; it decided to waste a large chunk of its valuable Olympics real estate promoting arguably the least promising new show it had at the time; developing a new channel for the terrestrial market, it launches one of the most badly thought out ad campaigns you'll ever see and makes programming decisions like pairing Munster, Go Home with a drama about a raped nun killing her newborn baby.

I don't have an explanation for what happened with NBC. I don't even have a good theory. I do however have a different way of framing the question. Instead of focusing on the styles and decisions of different executives, perhaps we should be asking how a company goes from hiring executives like Tinker and Tartikoff to hiring executives like Zucker and apparently many more like him.

* From Wikipedia:

Despite these failures, there were high points in Silverman's tenure at NBC, including the launch of the critically lauded Hill Street Blues (1981), the epic mini-series "Shogun" and The David Letterman Show (daytime, 1980), which would lead to Letterman's successful late night program in 1982. Silverman had Letterman in a holding deal after the morning show which kept the unemployed Letterman from going to another network. ...

Silverman also developed successful comedies such as Diff'rent Strokes, The Facts of Life, and Gimme a Break!, and made the series commitments that led to Cheers and St. Elsewhere. Silverman also pioneered entertainment reality programming with the 1979 launch of Real People. ... On Saturday mornings, in a time when most of the cartoon output of the three networks were similar, Silverman oversaw the development of an animated series based on The Smurfs; the animated series The Smurfs ran from 1981 to 1989, well after Silverman's departure, making it one of his longest-lasting contributions to the network. He also oversaw a revival of The Flintstones.

In other areas of NBC, Silverman revitalized the news division, which resulted in Today and NBC Nightly News achieving parity with their competition for the first time in years. He created a new FM Radio Division, with competitive full-service stations in New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Washington. During his NBC tenure, Silverman also brought in an entirely new divisional and corporate management, a team that stayed in place long after Silverman's departure. (Among this group was a new Entertainment President, Brandon Tartikoff, who would help get NBC back on top by 1985.)

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

Journalists vs. Lit Majors

Jonathan Chait has an insightful and sharply written piece up at New York Magazine called "Obama, ‘Leadership,’ and Magical Thinking." The whole thing is worth reading but this passage in particular jumped out at me because it illustrated a topic I'd been meaning to address.

When we talk about narrative in connection with today's journalists, we're generally using the term in a much older sense associated with a Trollope novel or a well-made play. Events follow a nice, clean causal chain. Moral issues are unambiguous and usually fairly obvious. Characters tend to be simple and fairly static except for some well-defined arcs and the occasional epiphany. All of which adds up to a final, objective truth.

Human beings think in terms of narrative. It's how we're wired and it's served us pretty well so far. The trouble is the narratives that dominate journalism today are excessively simplistic and journalists have an increasing tendency to converge mindlessly on whichever one seems to be the consensus opinion and to cling to it no matter how much evidence builds up against it.

But many political commentators find this analytic mode as dissatisfying as the quant approach to electoral forecasting. They understand politics largely in narrative terms, and the stories they prefer revolve around the success or failure of a lead character, who is always the president of the United States. If they reach back to history, it won’t be in any systematic way, but to tell stories of president Reagan drinking cocktails with Tip O’Neill, or Lyndon Johnson looming over a hapless member in a threatening fashion.We talk a lot about journalists and narrative but we don't mean narrative of the Twentieth Century sense of The Sound and the Fury or Rashomon. For the past hundred and twenty years or so, the vast majority of serious narrative art has been multidimensional and open-ended. There is often no objective truth. New information often only adds to the ambiguity. By the second half of the Twentieth Century, this type of narrative had also become common (prevalent?) in popular culture where characters like Lew Archer, George Smiley, Matthew Scudder, and even comic book superheroes faced ambiguous, morally and ethically murky landscapes that owed more to Joseph Conrad than to the Strand Magazine.

When we talk about narrative in connection with today's journalists, we're generally using the term in a much older sense associated with a Trollope novel or a well-made play. Events follow a nice, clean causal chain. Moral issues are unambiguous and usually fairly obvious. Characters tend to be simple and fairly static except for some well-defined arcs and the occasional epiphany. All of which adds up to a final, objective truth.

Human beings think in terms of narrative. It's how we're wired and it's served us pretty well so far. The trouble is the narratives that dominate journalism today are excessively simplistic and journalists have an increasing tendency to converge mindlessly on whichever one seems to be the consensus opinion and to cling to it no matter how much evidence builds up against it.

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Anti-orthogonality at Freakonomics

In one of the many recurring gags on the Beverly Hillbillies, whenever Jethro finished fixing the old flatbed truck, Jed would notice a small pile of engine parts on the ground next to the truck and Jethro would nonchalantly explain that those were the parts that were left over. I always liked that gag and the part that really sold it was the fact that the character saw this as a natural part of auto repair: when you took an engine apart then reassembled it you would always have parts left over.

Sometimes I find myself having a Jed moment when I read certain pop econ pieces.

"What's that pile next to your argument?"

"Oh, that's just some non-linear relationships, interactions, data quality issues and metrics that won't reduce to a scalar. We always have a bunch of stuff like that left over when we put together an argument."

I had one of those moments recently when I read this Freakonomics post by Dave Berri. Here's the key passage:

Right now we have two metrics that measure related properties based on different data. Though correlated (lots of big hits like Titanic have won major Oscars; relatively few flops have been so honored), these metrics often produce different rankings. This strikes Berri as a problem.

Note, we're not talking about the quality of these metrics, which are not that good (the Academy has serious issues while box office is confounded with factors like marketing, release date and number of screens), nor are we talking about the Academy's often discussed bias against certain genres. Those would be valid grounds for criticizing the awards (though I'm not sure how they would figure into a pop econ framework).

Berri is saying that metric B should incorporate metric A to make B more consistent with A. From a statistical standpoint, this is simply a bizarre statement. Statisticians want different variables to tell us different things. Assuming we wouldn't be able to disaggregate the role of box office in these new Academy awards, Berri's suggestion actually reduces the information in the system.

This is not an entirely abstract point. Movie goers do use the Oscars to make decisions as consumers.

In terms of the Oscars, this is a trivial discussion. (In terms of the Oscars, pretty much all discussions are.) Somewhat less trivial, however, is the accompanying discussion of the Freakonomics school of pop economics, currently one of the dominant influences on science writing for the mass audience. Writers of this school are noted for going into wide-ranging fields and finding interesting and unexpected results that often differ from the previous consensus. Sometime, though, those results are based not on logical steps you haven't thought of, but on steps you wouldn't think of as logical.

Sometimes I find myself having a Jed moment when I read certain pop econ pieces.

"What's that pile next to your argument?"

"Oh, that's just some non-linear relationships, interactions, data quality issues and metrics that won't reduce to a scalar. We always have a bunch of stuff like that left over when we put together an argument."

I had one of those moments recently when I read this Freakonomics post by Dave Berri. Here's the key passage:

Despite what seems like a clear endorsement by the customers of this industry, the Avengers was ignored by the Oscars. Perhaps this is just because I am an economist, but this strikes me as odd. Movies are not a product made just for the members the academy. These ventures are primarily made for the general public. And yet, when it comes time to decide which picture is “best,” the opinion of the general public seems to be ignored. Essentially the Oscars are an industry statement to their customers that says: “We don’t think our customers are smart enough to tell us which of our products are good. So we created a ceremony to correct our customers.”Andrew Gelman has already pointed out the odd mix of descriptive and normative here (and I think Joseph may have a post in mind that looks at underlying Randian attitudes about the rightness of the markets), but what struck me was how strange this seemed from a statistical standpoint.

Right now we have two metrics that measure related properties based on different data. Though correlated (lots of big hits like Titanic have won major Oscars; relatively few flops have been so honored), these metrics often produce different rankings. This strikes Berri as a problem.

Note, we're not talking about the quality of these metrics, which are not that good (the Academy has serious issues while box office is confounded with factors like marketing, release date and number of screens), nor are we talking about the Academy's often discussed bias against certain genres. Those would be valid grounds for criticizing the awards (though I'm not sure how they would figure into a pop econ framework).

Berri is saying that metric B should incorporate metric A to make B more consistent with A. From a statistical standpoint, this is simply a bizarre statement. Statisticians want different variables to tell us different things. Assuming we wouldn't be able to disaggregate the role of box office in these new Academy awards, Berri's suggestion actually reduces the information in the system.

This is not an entirely abstract point. Movie goers do use the Oscars to make decisions as consumers.

Oscar-nominated films remain in theaters about twice as long as others, according to a report by Randy Nelson, professor of economics and finance at Colby College.Just to sum things up, Berri is suggesting that we should reduce the quality of a data source that consumers make extensive use of because, since the data sometimes doesn't align with consumers' previous revealed preference, that data is somehow insulting to those consumers.

...

Nelson found that a nomination for Best Actor or Best Actress increases box office revenue by about $683,660 (we adjusted the values from the 2001 report to 2012 dollars). For Best Picture, the boost jumps to $6.9 million.

...

Taking home a big award has an even greater impact: Based on Nelson’s study, a Best Picture win boosts box office sales by $18.1 million, on average, and a Best Actor or Actress win by $5.8 million. Even a Supporting Actor or Actress award increases sales by $2.3 million.

In terms of the Oscars, this is a trivial discussion. (In terms of the Oscars, pretty much all discussions are.) Somewhat less trivial, however, is the accompanying discussion of the Freakonomics school of pop economics, currently one of the dominant influences on science writing for the mass audience. Writers of this school are noted for going into wide-ranging fields and finding interesting and unexpected results that often differ from the previous consensus. Sometime, though, those results are based not on logical steps you haven't thought of, but on steps you wouldn't think of as logical.

Monday, May 13, 2013

While we're on a literary thread...

I'm looking for the name of a Lord Dunsany story about a banker who loses his job because he becomes obsessed with chess. The ending has become almost indescribably apt.

Sunday, May 12, 2013

I hope I don't get into too much trouble over this

I mentioned game theory in a recent post but I forgot the rule that whenever you mention that field of study, you are required by law to also mention the prisoner's dilemma no matter how completely freaking inapplicable it is to the discussion. See the Los Angeles Review of Books for the latest case in point.

A couple more thoughts on Oregon

Aaron Carroll (writing for the Incidental Economist) points out one interesting result of the new study:

All by itself this finding is a worthwhile addition to the discussion; the meme that Medicaid coverage could lead to worse health outcomes was always a bit tricky to understand. Trying to illicit a causal mechanism where Medicaid was worse for health but private insurance/Medicare were not that led naturally to the policy of "end Medicaid" was always a bit dicey. If it was malice on the part of medical doctors due to low reimbursement rates then that rather changes the discussion in important ways.

So I think we should take this argument by Megan McArdle with a great deal of care:

I think that there are two points here. One, the point estimates of the changes for chronic medical conditions are well within the levels of clinical significance. So it is odd to suddenly interpret the data like an extreme frequentist and claim that the only interpretation is "no effect".

But the other piece that is more important is that this is actually a good result. If we take Megan's 5% rate, that would mean that 5% of poor Americans have a catastrophic medical bill within a two year period. How can trying to solve that problem not be a major priority? Isn't this great evidence that (given how expensive medicine has gotten) that this was a massively successful intervention?

I'd have more sympathy for the situation if we were making hard decisions to bring down costs. But that isn't a major priority right now. Medicaid is a very cost effective way to deliver care in a country where care is very pricey. Why isn't this a major and positive result?

Not too long ago, ACA opponents were claiming that Medicaid was bad for health. Some even claimed it killed people. So I was eager to see if an RCT would find that. The initial results were positive and statistically significant.

All by itself this finding is a worthwhile addition to the discussion; the meme that Medicaid coverage could lead to worse health outcomes was always a bit tricky to understand. Trying to illicit a causal mechanism where Medicaid was worse for health but private insurance/Medicare were not that led naturally to the policy of "end Medicaid" was always a bit dicey. If it was malice on the part of medical doctors due to low reimbursement rates then that rather changes the discussion in important ways.

So I think we should take this argument by Megan McArdle with a great deal of care:

And yet, we did find a significant improvement in catastrophic medical bills, which coincidentally also affect about 5% of the control group. Yet the folks saying Oregon's sample of diabetics is too small to tell us anything do not think it is too small to tell us anything about catastrophic medical bills.

I think that there are two points here. One, the point estimates of the changes for chronic medical conditions are well within the levels of clinical significance. So it is odd to suddenly interpret the data like an extreme frequentist and claim that the only interpretation is "no effect".

But the other piece that is more important is that this is actually a good result. If we take Megan's 5% rate, that would mean that 5% of poor Americans have a catastrophic medical bill within a two year period. How can trying to solve that problem not be a major priority? Isn't this great evidence that (given how expensive medicine has gotten) that this was a massively successful intervention?

I'd have more sympathy for the situation if we were making hard decisions to bring down costs. But that isn't a major priority right now. Medicaid is a very cost effective way to deliver care in a country where care is very pricey. Why isn't this a major and positive result?

Thrillers on Economics -- Updated

Noah Smith has garnered a lot of attention for his recent post on economics in science fiction. Not surprising given that much of the genre involves thought experiments about alternate ways of organizing society. Furthermore, lots of economists are fans of the genre (Paul Krugman even wrote an introduction to a recent edition of the Foundation Trilogy).

I doubt you'll find as many fans in the dismal science of crime novels but for those of you out there, here's a post we ran a while back about books that look at econ and business from the noir side, followed by some titles that occurred to me since the initial posting:

Of the many crime novels built around businesses, the best might be Murder Must Advertise, a Lord Whimsey by Dorothy L. Sayers. The story is set in a London ad agency in the Thirties, a time when the traditional roles of the aristocracy were changing and "public school lads" were showing up in traditional bourgeois fields like advertising.

Sayers had been a highly successful copywriter (variations on some of her campaigns are still running today) and has sometimes been credited with coining the phrase "It pays to advertise." All this success did not soften her view of the industry, a view which is probably best captured by Whimsey's observation that truth in advertising is like yeast in bread.

But even if Sayers holds the record for individual event, the lifetime achievement award has got to go to the man whom many* consider the best American crime novelist, John D. MacDonald.(If you'd like to learn more about MacDonald, Andrew Gelman doesn't exactly recommend this book.)

Before trying his hand at writing, MacDonald had earned an MBA at Harvard and over his forty year writing career, business and economics remained a prominent part of his fictional universe (one supporting character in the Travis McGee series was an economist who lived on a boat called the John Maynard Keynes). But it was in some of the non-series books that MacDonald's background moved to the foreground.

Real estate frequently figured in MacDonald's plots (not that surprising given given their Florida/Redneck Riviera settings). His last book, Barrier Island, was built around a plan to work federal regulations and creative accounting to turn a profit from the cancellation of a wildly overvalued project. In Condominium, sleazy developers dodge environmental regulations and building codes (which turned out to be a particularly bad idea in a hurricane-prone area).

Real estate also figures MacDonald's examination of televangelism, One More Sunday, as does almost every aspect of an Oral Roberts scale enterprise, HR, security, public relations, lobbying, broadcasting and most importantly fund-raising. It's a complete, realistic, insightful picture. You can find companies launched with less detailed business plans.

But MacDonald's best book on business may be A Key to the Suite, a brief and exceedingly bitter account of a management consultant deciding the future of various executives at a sales convention. Suite was published as a Gold Medal Original paperback in 1962. You could find a surprising amount of social commentary in those drugstore book racks, usually packaged with lots of cleavage.

* One example of many:

“To diggers a thousand years from now, the works of John D. MacDonald would be a treasure on the order of the tomb of Tutankhamen.” - KURT VONNEGUT

I omitted MacDonald's own probable choice for his best business story "The Trap of Solid Gold" because I misplaced my copy of End of the Tiger before I got to it. It is very much on my to-read list.

I also left out Donald Westlake's novel about union organizers, Killy and I have no idea why. This is straight Westlake (as compared with comic Westlake and tough-guy Westlake) and it's quite good, with both characters and institutions growing more morally ambiguous as the story progresses.

You can get an interesting take on the way many economies actually worked in the novels of Eric Ambler, where ill-equipped, often stateless protagonists try to do business (sometimes legally) while navigating the corrupt, Byzantine bureaucracies of multiple countries. Hard to believe that before Ambler, the face of the British spy novel was John Buchan.

Lawrence Block is an exceptionally intelligent writer who can be counted on for sharp observations. "Batman's Helpers" (along with "the Cold Equations" and Block's friend Westlake's Levine stories, one of the most memorable of the anti-genre genre stories) addresses, of all things, copyright while The Burglar who Painted like Mondrian plays a series of witty games with the question of value.

I know I'm missing lots a examples. Maybe Smith will do another science fiction post in a couple of years and I'll take another whack.

P.S. Andrew Gelman nominates George V. Higgins as the crime novelist with the most focus on economics. Having slept on it, I'm wondering if we should stretch things to include game theory. That might lead to an interesting take on Hammett's Red Harvest and its many imitators. In terms of strategically supplying or withholding information in multiplayer games, Erle Stanley Gardner came up with all sorts of interesting variations in his novels and, if the anecdotes are to be believed, in his actual law practice as well (those who like more focus on character should start with the Cool and Lam books). Maybe someone could write a paper of game theory in Black Mask.

P.P.S. Prisoner's dilemma.

Saturday, May 11, 2013

The Pauline Kael Rule strikes again

[Posts are like the hydra, every time you do the research for one post you end up with two more that you want to write. Maybe that's why so many journalists have given up fact checking.]

A few days ago, a friend and I were discussing movies and the subject of films that cast Keanu Reeves in a lead role and emerge unscathed came up. Speed was one of the few names that came up.

Then yesterday when I was checking background for a post that mentioned Joss Whedon I came across this:

I once jotted down the names of some movies that I didn’t associate with any celebrated director but that had nevertheless stayed in my memory over the years, because something in them had especially delighted me—such rather obscure movies as The Moon’s Our Home (Margaret Sullavan and Henry Fonda) and He Married His Wife (Nancy Kelly, Joel McCrea, and Mary Boland). When I looked them up, I discovered that Dorothy Parker’s name was in the credits of The Moon’s Our Home and John O’Hara’s in the credits of He Married His Wife. Other writers worked on those films, too, and perhaps they were the ones who were responsible for what I responded to, but the recurrence of the names of that group of writers, not just on rather obscure remembered films but on almost all the films that are generally cited as proof of the vision and style of the most highly acclaimed directors of that period, suggests that the writers—and a particular group of them, at that—may for a brief period, a little more than a decade, have given American talkies their character.from Raising Kane by Pauline Kael

A few days ago, a friend and I were discussing movies and the subject of films that cast Keanu Reeves in a lead role and emerge unscathed came up. Speed was one of the few names that came up.

Then yesterday when I was checking background for a post that mentioned Joss Whedon I came across this:

According to Graham Yost, the credited writer of Speed, Whedon wrote most of the film's dialogueWhedon, of course, needs no introduction and (with the qualifier that I haven't had a chance to check out Homeland and Game of Thrones) Yost has created my choice for best show currently on TV.

Friday, May 10, 2013

When similar inputs produce radically different outputs -- more on Kickster

[Following up this]

Ken Levine has a follow-up to his widely-read post on the Kickstarter campaigns of Zach Braff and Rob Thomas (creator of Veronica Mars). Well worth checking out (as are most of Levine's posts) but this in particular caught my eye:

That said, Mars strikes me as an even worse fit for Kickstarter than the Braff project. Consider a thought experiment: imagine you had never heard of any of the people involved in either project. If you read descriptions of the Veronica Mars Movie Project and Braff's Wish I Was Here, which one would sound like a Kickstarter project? Not which one is a better idea. Not which one you'd like to see. Which one sounds like a Kickstarter project.

I haven't followed Kickstarter that closely but Braff's indier-than-thou concept certainly seems more Kickstarter. Nonetheless Thomas seems to be getting less criticism and will probably end up getting more money.

The specific lesson I'd draw from this is that fans of high-concept television are disproportionately likely to be active online and to pledge money to a Kickstarter campaign. The general lesson is that, from a marketing and demographic perspective, the internet is different than the real world.

It's true that most people are online but some are on a lot more than others and those heavy users are not representative of the general public (if they were, Veronica Mars would have broken the top 100 -- or just the top 120 -- at some point in its three year run). Add to this the potential for fraud, the tendency to rack up deceptively large numbers, the susceptibility to trends, and the hopelessly complicated relationship between the internet and the rest of the media which further distorts an already muddled picture.

We constantly hear about some overnight internet sensation and are told it represents the future of retailing, the future of education, the future of philanthropy, the future of _____. The trouble is many of these successes don't stand up to scrutiny and those that do often prove not to be sustainable and /or scalable. The internet can be a great source of business ideas. Because of its fast turnaround time and low barriers to entry it can be a great place to try out something new.

But some of these lessons don't generalize very well.

p.s. It is also good to know that not every former sitcom star finds gold in the hills of Kickstarter.

Ken Levine has a follow-up to his widely-read post on the Kickstarter campaigns of Zach Braff and Rob Thomas (creator of Veronica Mars). Well worth checking out (as are most of Levine's posts) but this in particular caught my eye:

And finally, a lot of you agreed with me about Zach Braff but not VERONICA MARS. You pointed out that creator Rob Thomas did try for years to get Warner Brothers to make it and they flatly refused. This was a viable alternative. There would be no VERONICA MARS movie had it not been for Kickstarter. Fair enough and I’m looking forward to seeing it. I also give Rob Thomas points for ingenuity. He was the first to use Kickstarter in this regard.First off, I think Rob Thomas is an extraordinary talent and I readily put him in the company of writer-producers like Joss Whedon and Matt Nix who not only have rediscovered the lost art (at least in America) of high-concept television, but have brought a new subtlety and dramatic range to the genres. I'd love to see a Veronica Mars movie.

That said, Mars strikes me as an even worse fit for Kickstarter than the Braff project. Consider a thought experiment: imagine you had never heard of any of the people involved in either project. If you read descriptions of the Veronica Mars Movie Project and Braff's Wish I Was Here, which one would sound like a Kickstarter project? Not which one is a better idea. Not which one you'd like to see. Which one sounds like a Kickstarter project.

I haven't followed Kickstarter that closely but Braff's indier-than-thou concept certainly seems more Kickstarter. Nonetheless Thomas seems to be getting less criticism and will probably end up getting more money.

The specific lesson I'd draw from this is that fans of high-concept television are disproportionately likely to be active online and to pledge money to a Kickstarter campaign. The general lesson is that, from a marketing and demographic perspective, the internet is different than the real world.

It's true that most people are online but some are on a lot more than others and those heavy users are not representative of the general public (if they were, Veronica Mars would have broken the top 100 -- or just the top 120 -- at some point in its three year run). Add to this the potential for fraud, the tendency to rack up deceptively large numbers, the susceptibility to trends, and the hopelessly complicated relationship between the internet and the rest of the media which further distorts an already muddled picture.

We constantly hear about some overnight internet sensation and are told it represents the future of retailing, the future of education, the future of philanthropy, the future of _____. The trouble is many of these successes don't stand up to scrutiny and those that do often prove not to be sustainable and /or scalable. The internet can be a great source of business ideas. Because of its fast turnaround time and low barriers to entry it can be a great place to try out something new.

But some of these lessons don't generalize very well.

p.s. It is also good to know that not every former sitcom star finds gold in the hills of Kickstarter.

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Paul Ryan's Coonskin Cap

Davy Crockett may have been the first great American political fabrication. He really was a woodsman and guide of note and, though there is some disagreement on this point, he probably went down fighting at the Alamo. As a legend, though, "Davy Crockett" was largely a creation of the Whigs who were desperate to counter the man-of-the-frontier threat posed by Andrew Jackson. If memory serves, Crockett himself deeply resented being reduced to a walking self-parody.

It was fairly easy to forgive that sort of thing in the 1830 when journalists were working with limited technology and crude institutions. These days, there is not really a good excuse for passing along an obviously manufactured persona, but the practice continues. Hell, it might even be on the upswing.

The first President elected (rather than re-elected) during the Internet Age was successfully marketed as a plain-spoken cowboy despite being on the record as having a strong aversion to cowboy boots and being deathly afraid of horses* (google "Vicente Fox George Bush Horses"). Bush was, of course, the Republicans' answer to Bill Clinton's man-of-the-people appeal just as Crockett was the Whigs' answer to Jackson. I read Age of Jackson early in the Bush years and I always wondered why more wasn't made of the parallel.

Currently, the fabrication du jour is Paul Ryan -- honest conservative, dedicated policy wonk, everyday guy. Jonathan Chait, Paul Krugman and others had seemingly taken apart the Ryan edifice so thoroughly that there was no stone on stone, then salted the ground so that nothing there again shall grow, but we are dealing with some hardy weeds.

Here Michael Scherer does some serious cultivating:

The Belgian restaurant lists 115 beers on its menu, but not Miller Lite, Ryan’s beer of choice. “I ended up getting some lager I’d never heard of,” said Ryan, who mistook the place for a French joint. But it turned out McDonough had done his homework in other ways. He knew that Ryan had graduated from Miami University in Ohio the same year as his own wife Kari. Both men hailed from former frontier towns in the upper Midwest, and both had been drawn to Washington as young congressional aides. They were nerds, in the best sense of the word, and they were fierce competitors.Not surprisingly, Chait takes this one apart: