As with so many things, the late 19th and early 20th centuries seem to represent the turning point for a modern perspective on nutrition. As far as I can tell, this is the point at which people started thinking of nutrition as a chemistry problem: you take food into a laboratory, analyze the constituent parts, and optimize the things you need while minimizing the things you don't.

The thing that jumps out at the modern reader as particularly off key is the treatment of fiber. I'm assuming “crude” in this context means insoluble, but it is still odd to see fiber treated as an undesirable component.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Wednesday, March 14, 2018

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

When the NIMBYs were primarily motivated by racism and class bigotry, there was no NIMBY backlash. *

We've commented before that much of the discussion of urban density, particularly on the advocates' side, tends to be overly simplistic and inappropriately moralistic. This last point is greatly complicated by the fact that historically the motivations for NIMBYism were more often than not pretty repugnant. Opposition to public transportation, low-cost housing, and integration of neighborhoods was based almost entirely on the desire to keep people of color and the poor as far away as possible.

These issues haven't gone away, of course – – try to add another subway stop in Beverly Hills and check out the response you get – – but the NIMBY/YIMBY conflict that makes the news and dominates the public discourse here in Los Angeles (and, I suspect, in the Bay Area as well) has very little racial and class component.

At best, the battle over Santa Monica is a struggle between the top decile and the top quartile. Sometimes, there's not even that much of a class distinction. To be hammer blunt, you have a bunch of well-off people who enjoy the fantastic weather and bland conspicuous consumption of the town and who don't want other well-off people coming in and clogging the place up.

Advocates generally argue that development will drive down prices both in the city of Santa Monica and in the county of Los Angeles. I'm skeptical. While I'm not saying this is a bad approach in general, the arguments I've seen so far seem simplistic and overly linear, and the proposed impacts wildly overoptimistic. I could easily be wrong on these questions but either way, this is not a moral argument and framing it in moralistic terms simply serves to cloud the issues.

These issues haven't gone away, of course – – try to add another subway stop in Beverly Hills and check out the response you get – – but the NIMBY/YIMBY conflict that makes the news and dominates the public discourse here in Los Angeles (and, I suspect, in the Bay Area as well) has very little racial and class component.

At best, the battle over Santa Monica is a struggle between the top decile and the top quartile. Sometimes, there's not even that much of a class distinction. To be hammer blunt, you have a bunch of well-off people who enjoy the fantastic weather and bland conspicuous consumption of the town and who don't want other well-off people coming in and clogging the place up.

Advocates generally argue that development will drive down prices both in the city of Santa Monica and in the county of Los Angeles. I'm skeptical. While I'm not saying this is a bad approach in general, the arguments I've seen so far seem simplistic and overly linear, and the proposed impacts wildly overoptimistic. I could easily be wrong on these questions but either way, this is not a moral argument and framing it in moralistic terms simply serves to cloud the issues.

* Should read YIMBY backlash

Monday, March 12, 2018

We won't even get into the return of vinyl...

I'm assuming that everyone has heard the buggy whip analogy, one of the most shopworn pieces of conventional business wisdom. One of the underlying assumptions, sometimes made explicit depending on who's doing the telling, is that you are always better off abandoning even the best company in a declining industry in order to make the move to a field that's new and growing.

It's important to note that even in declining industries you can find companies that continue to turn a profit for a long time while even in industries that do proved to be the wave of the future, lots of individual companies don't last that long.

Or, put another way, you can still buy a buggy whip from the Westfield Whip Manufacturing Company, but they stopped making Lamberts a long time ago.

Friday, March 9, 2018

The checkers speech was made in 1952.

I know you know that – – everyone knows that – – but think about the implications for a moment. This nationally televised speech is often credited with saving the career of Richard Nixon and making him one of the dominant forces in American politics for the next 20 years. It was unquestionably a turning point in the way that public figures used media, particularly in the face of scandal.

And it happened in 1952.

What's the big deal? Remember that television was still in its experimental phase until the postwar era. It wasn't until around 1947 that it became a national medium and even then, large swaths of the country had no TV stations. The fate of a presidential ticket was determined by something that was, at best, five years old.

When you hear the claim that technology today is changing our lives faster than ever before, remember Checkers.

And it happened in 1952.

What's the big deal? Remember that television was still in its experimental phase until the postwar era. It wasn't until around 1947 that it became a national medium and even then, large swaths of the country had no TV stations. The fate of a presidential ticket was determined by something that was, at best, five years old.

When you hear the claim that technology today is changing our lives faster than ever before, remember Checkers.

Thursday, March 8, 2018

All of this would look remarkably modern if not for the horse drawn carriages

What struck me about this 1903 cover from Scientific American was the way planners set aside dedicated spaces for different modes of travel, one level for pedestrians, one for cyclists, one for automobiles and carriages, and two for trains, an allotment that would no doubt please many urbanists today.

This begs the question, did this approach to urban transportation fall out of fashion? Or was it one of those things that had a way of showing up in proposals but which seldom made it to the groundbreaking?

This begs the question, did this approach to urban transportation fall out of fashion? Or was it one of those things that had a way of showing up in proposals but which seldom made it to the groundbreaking?

Wednesday, March 7, 2018

Seems like a good time to reopen this thread.

This post by Jonathan Chait about the renewed demographic threat faced by the GOP got me thinking about a thread I've been meaning to revisit.

If I were writing this today, there are obviously things I would handle differently, but I'm reasonably comfortable standing by the main points.

But, just as Trump's rise did not occur in a vacuum, neither will his fall. We discussed earlier how Donald Trump has the power to drive a wedge between the Republican Party and a significant segment of its base [I wrote this before the departure of Steve Bannon. That may diminish Trump's ability to create this rift but I don't think it reduces the chances of the rift happening. – – M.P.]. This is the sort of thing that can profoundly damage a political party, possibly locking it into a minority status for a long time, but normally the wound would not be fatal. These, however, are not normal times.

The Republican Party of 2017 faces a unique combination of interrelated challenges, each of which is at a historic level and the combination of which would present an unprecedented threat to this or any US political party. The following list is not intended to be exhaustive, but it hits the main points.

The GOP currently has to deal with extraordinary political scandals, a stunningly unpopular agenda and daunting demographic trends. To keep things symmetric and easy to remember, let's break each one of these down to three components (keeping in mind that the list may change).

With the scandals:

1. Money – – Even with the most generous reading imaginable, there is no question that Trump has a decades long record of screwing people over, skirting the law, and dealing with disreputable and sometimes criminal elements. At least some of these dealings have been with the Russian mafia, oligarchs, and figures tied in with the Kremlin which leads us to…

2. The hacking of the election – – This one is also beyond dispute. It happened and it may have put Donald Trump into the White House. At this point, we have plenty of quid and plenty of quo; if Mueller can nail down pro, we will have a complete set.

3. And the cover-up – – As Josh Marshall and many others have pointed out, the phrase "it's not the crime; it's the cover-up" is almost never true. That said, coverups can provide tipping points and handholds for investigators, not to mention expanding the list of culprits.

With the agenda:

1. Health care – – By some standards the most unpopular major policy proposal in living memory that a party in power has invested so deeply in. Furthermore, the pushback against the initiative has essentially driven congressional Republicans into hiding from their own constituents for the past half year. As mentioned before, this has the potential to greatly undermine the relationship between GOP senators and representatives and the voters.

2. Tax cuts for the wealthy – – As said many times, Donald Trump has a gift for making the subtle plain, the plain obvious, and the obvious undeniable. In the past, Republicans were able to get a great deal of upward redistribution of the wealth past the voters through obfuscation and clever branding, but we have reached the point where simply calling something "tax reform" is no longer enough to sell tax proposals so regressive that even the majority of Republicans oppose them.

3. Immigration (subject to change) – – the race for third place in this list is fairly competitive (education seems to be coming up on the outside), but the administration's immigration policies (which are the direct result of decades of xenophobic propaganda from conservative media) have already done tremendous damage, caused great backlash, and are whitening the gap between the GOP and the Hispanic community, which leads us to…

Demographics:

As Lindsey Graham has observed, they simply are not making enough new old white men to keep the GOP's strategy going much longer, but the Trump era rebranding of the Republican Party only exacerbates the problems with women, young people, and pretty much anyone who isn't white.

Maybe I am missing a historical precedent here, but I can't think of another time that either the Democrats or the Republicans were this vulnerable on all three of these fronts. This does not mean that the party is doomed or even that, with the right breaks, it can't maintain a hold on some part of the government. What it does mean is that the institution is especially fragile at the moment. A mortal blow may not come, but we can no longer call it unthinkable.

For obvious reasons, the broadly liberal demographic trends in American politics have received much less attention since the 2016 election. Yet the fact remains that America is politically sorted by generations in a way it never has before. The oldest voters are the most conservative, white, and Republican, and the youngest voters the most liberal, racially diverse, and Democratic. There is absolutely no sign the dynamic is abating during the Trump years. If anything, it is accelerating.In the first few months of the Trump administration, we did a series of posts on how the underlying dynamics of the Republican Party were changing and what some of the consequences might be. One of the fundamental ideas of the thread was that the country had entered a period where our normal ways of talking about subjective probability made no sense in terms of politics. You could still make directional and even ordinal statements, but we were so far outside of the range of data and precedent that you could no longer confidently assign upper and lower bounds to the probability of a number of events including the destruction of the Republican Party. Note, I never said that this was "likely" to happen, but rather you can't say that it can't happen now.

The most recent Pew Research Survey has more detail about the generational divide. It shows that the old saw that young people would naturally grow more conservative as they age, or that their Democratic loyalties were an idiosyncratic response to Barack Obama’s unique personal appeal, has not held. Younger voters have distinctly more liberal views than older voters:

One could probably quibble with the overall definitions of which voters have liberal views and which have conservative views. What’s telling here is the comparison between generations. By Pew’s given definition, younger voters are wildly more liberal than older ones. The youngest voters have nearly five times as many voters with liberal views than with conservative views. The oldest voters have one and a half times more conservative than liberal voters.

Correspondingly, the Democratic lean of millennial voters is as strong as ever:

In the upcoming midterm elections, millennials are providing a huge share of the Democrats’ edge, with older generations splitting their vote relatively close:

If I were writing this today, there are obviously things I would handle differently, but I'm reasonably comfortable standing by the main points.

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

The Republicans' 3 x 3 existential threat

I've argued previously that Donald Trump presents and existential threat to the Republican Party. I know this can sound overheated and perhaps even a bit crazy. There are few American institutions as long-standing and deeply entrenched as are the Democratic and Republican parties. Proposing that one of them might not be around 10 years from now beggars the imagination and if this story started and stopped with Donald Trump, it would be silly to suggest we were on the verge of a political cataclysm.But, just as Trump's rise did not occur in a vacuum, neither will his fall. We discussed earlier how Donald Trump has the power to drive a wedge between the Republican Party and a significant segment of its base [I wrote this before the departure of Steve Bannon. That may diminish Trump's ability to create this rift but I don't think it reduces the chances of the rift happening. – – M.P.]. This is the sort of thing that can profoundly damage a political party, possibly locking it into a minority status for a long time, but normally the wound would not be fatal. These, however, are not normal times.

The Republican Party of 2017 faces a unique combination of interrelated challenges, each of which is at a historic level and the combination of which would present an unprecedented threat to this or any US political party. The following list is not intended to be exhaustive, but it hits the main points.

The GOP currently has to deal with extraordinary political scandals, a stunningly unpopular agenda and daunting demographic trends. To keep things symmetric and easy to remember, let's break each one of these down to three components (keeping in mind that the list may change).

With the scandals:

1. Money – – Even with the most generous reading imaginable, there is no question that Trump has a decades long record of screwing people over, skirting the law, and dealing with disreputable and sometimes criminal elements. At least some of these dealings have been with the Russian mafia, oligarchs, and figures tied in with the Kremlin which leads us to…

2. The hacking of the election – – This one is also beyond dispute. It happened and it may have put Donald Trump into the White House. At this point, we have plenty of quid and plenty of quo; if Mueller can nail down pro, we will have a complete set.

3. And the cover-up – – As Josh Marshall and many others have pointed out, the phrase "it's not the crime; it's the cover-up" is almost never true. That said, coverups can provide tipping points and handholds for investigators, not to mention expanding the list of culprits.

With the agenda:

1. Health care – – By some standards the most unpopular major policy proposal in living memory that a party in power has invested so deeply in. Furthermore, the pushback against the initiative has essentially driven congressional Republicans into hiding from their own constituents for the past half year. As mentioned before, this has the potential to greatly undermine the relationship between GOP senators and representatives and the voters.

2. Tax cuts for the wealthy – – As said many times, Donald Trump has a gift for making the subtle plain, the plain obvious, and the obvious undeniable. In the past, Republicans were able to get a great deal of upward redistribution of the wealth past the voters through obfuscation and clever branding, but we have reached the point where simply calling something "tax reform" is no longer enough to sell tax proposals so regressive that even the majority of Republicans oppose them.

3. Immigration (subject to change) – – the race for third place in this list is fairly competitive (education seems to be coming up on the outside), but the administration's immigration policies (which are the direct result of decades of xenophobic propaganda from conservative media) have already done tremendous damage, caused great backlash, and are whitening the gap between the GOP and the Hispanic community, which leads us to…

Demographics:

As Lindsey Graham has observed, they simply are not making enough new old white men to keep the GOP's strategy going much longer, but the Trump era rebranding of the Republican Party only exacerbates the problems with women, young people, and pretty much anyone who isn't white.

Maybe I am missing a historical precedent here, but I can't think of another time that either the Democrats or the Republicans were this vulnerable on all three of these fronts. This does not mean that the party is doomed or even that, with the right breaks, it can't maintain a hold on some part of the government. What it does mean is that the institution is especially fragile at the moment. A mortal blow may not come, but we can no longer call it unthinkable.

Tuesday, March 6, 2018

I guess I'll force myself to have a chocolate malt

I'd like to see a list of all of the foods that were originally sold on the basis of health but which now survive as unhealthy indulgences. In addition to malted milk, many early soft drinks fall into this category and I have the feeling I'm missing some other obvious examples.

From Scientific American 1908-12-05

From Scientific American 1908-12-05

Monday, March 5, 2018

Hyperloop watch -- We are now reaching that part of the movie where the wife goes to the bank and realizes that her husband has given their life savings to the con man.

I know I've been harping on this for years now and I'd imagine regular readers are growing a bit tired of the ranting, but the standard tech narrative, the one that is still more or less the default for even sober news organizations like the BBC and NPR, is deeply flawed and genuinely dangerous.

The hype and bullshit and magical heuristics that dominate our discussion of technology and innovation aren't just annoying; they have a real cost. They distort markets, spread misinformation, lead to bad public policy, and starve worthwhile initiatives of both funding and attention.

No figure brings out the worst of these tendencies in journalists more than does Elon Musk. Musk, it should be noted, does have some major accomplishments under his belt as an administrator, promoter, and finance guy. With SpaceX and, to a lesser degree, Tesla, he deserves considerable credit for significant innovations, but even with his most serious projects, there is always a bit of the Flimflam Man present.

The Hyperloop has always been Elon Musk at his most substance-free. A 70s era B- senior engineering project dressed up with 3-D graphics and a cool name. Despite being thoroughly demolished by virtually every independent expert in the field, the "proposal" has generated endless and endlessly credulous press coverage. Hundreds of millions of dollars in financing have been lined up by Hyperloop companies with dubious business plans. And now you can add millions in tax dollars to that.

From an excellent Slate article by Henry Grabar.

For American lawmakers, funding public transit often feels like small ball. Politicians prefer to dream bigger. Earlier this month, transportation agencies in the Cleveland region and in Illinois announced they would co-sponsor a $1.2 million study of a “hyperloop” connecting Cleveland to Chicago, cutting a 350-mile journey to just half an hour. It’s the fourth public study of the nonexistent transportation mode to be undertaken in the past three months.

“Ohio is defined by its history of innovation and adventure,” said Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who once canceled a $400 million Obama-era grant for high-speed rail in the state. “A hyperloop in Ohio would build upon that heritage.” In January, a bipartisan group of Rust Belt representatives wrote to President Trump to ask for $20 million in federal funding for a Hyperloop Transportation Initiative, a Department of Transportation division that would regulate and fund a travel mode with no proof of concept.

It’s hard to keep up: Last week, the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission announced feasibility and environmental-impact studies for a different hyperloop route, connecting Pittsburgh and Chicago through Columbus, Ohio, to be run by a different company, Virgin Hyperloop One. The company—which fired a pod through a tube at 240 mph in December—is also studying routes in Missouri and Colorado.* Meanwhile, Elon Musk—who has obtained (contested) tunneling permission from Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan—pulled a permit from the District of Columbia for a future hyperloop station.

But let’s first look at the hyperloop [from our old friends, the incredibly flaky, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies -- MP] that Grace Gallucci, the head of the Cleveland regional planning association the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), told local radio could be running to Chicago in three to five years, and to the study of which the NOACA contributed $600,000.

Friday, March 2, 2018

Explaining the principal-agent problem

I thought I posted this years ago.

The Butler and the Maid from The Carol Burnett Show

The Butler and the Maid from The Carol Burnett Show

Thursday, March 1, 2018

Urban suburbs

My first corporate job also led to my first big move. I'd bounced around before that, between teaching and going off to grad school, but the moves had, at most, entailed crossing only one state line. The corporate position took me from just west of the Mississippi to the East Coast, with no social contacts or experience of the area to draw on.

I did what seemed like the sensible thing and got an apartment a few minutes from work. The company's campus was on the outskirts of town deep in the suburbs. Before that, I had lived in the country, small towns, and a couple of urban areas. Each of those three options had some strong pluses and, under the right conditions, could be quite appealing. By comparison, suburban living, at least without kids, had nothing to recommend it as far as I was concerned. I realized quickly but still too late that I should have picked an interesting neighborhood closer to the center of town, even though that would've meant an extra 20 or 30 minutes of commuting per day.

I did not repeat that mistake for my next job. Before moving, I scouted the area and ask around before deciding on a very cool neighborhood featuring lots of restaurants, bars, and the city's best art-house movie theater within easy walking distance. My daily commute was 45 minutes to an hour, but the traffic wasn't bad and much of it skirted around (and at one point across) the Chesapeake Bay making for a relaxing and scenic beginning and in to each workday.

That neighborhood was, for me, functioning as a de facto suburb. I was trading a longer commute for more desirable living conditions. The fact that these more desirable conditions were found in an area of higher density, rather than lower, does not affect the underlying dynamic.

One of the primary tenets of faith among utopian urbanists is that making it dense areas more dense will have a range of tremendously beneficial effects starting with great reductions in commuting and suburban sprawl. The existence of urban suburbs raises serious questions about that argument.

How big a deal is this? A good urban researcher could probably provide us with fairly reliable numbers, but we can say with some confidence that it's having a sizable effect in at least isolated cases. San Francisco has clearly become an urban suburb for Silicon Valley and, to a degree, Santa Monica and the rapidly gentrifying Venice Beach often fill the same role for much of Los Angeles.

It is worth noting that San Francisco followed by Santa Monica are probably the two cities that density proponents are most passionate about. This raises a disturbing question (and one which, I suspect, researchers will find more difficult to answer): if you greatly increase the density of cities that are already largely functioning as urban suburbs, will you in effect simply be producing more suburban sprawl?

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

"A space engine that could make flying into orbit commonplace"

Obviously, you can't compare a piece of technology in development to one that's up and working. The Falcon Heavy isn't a proposal or a prototype; it's a viable vehicle currently in use. The engineers at SpaceX deserve a great deal of credit for solving daunting technical challenges, but it's important to note that it took them much longer than they anticipated and, more to the point, there's nothing revolutionary about the technology. For that, you'd have to look someplace like this.

Sabre: the ‘Holy Grail’ in space technology

Researchers have spent decades trying to crack the problem of how to fly from earth to space and back again, writes Peggy Hollinger.

But it took a combination of rocket and nuclear science to make the breakthrough that is now drawing interest from around the world in Reaction Engines’ Sabre technology.

“It was pretty clear that the rocket needed a bit of a leg up and the only place to get that was from the Earth’s atmosphere,” says Alan Bond, one of Reaction Engines’ three founders.

“But the [speed] you get out of conventional jet engines isn’t enough. Somewhere in 1982 . . . I realised that a bit of theory I had used on nuclear engines 10 years before could actually help. So the hybrid air-breathing rocket engine came into existence.”

The engine combines jet and rocket technologies thanks to its unique pre-cooler, which extracts heat from air flowing in at high speeds of up to Mach 5 — several times the speed of sound.

This enables it to be used by the engine, which then uses the heat energy to power a turbocompressor. When at the edge of the atmosphere, the engine switches into rocket mode, using liquid oxygen to break through into orbit.

Unlike partially re-usable launchers being developed by the likes of SpaceX of the US, Sabre does not need to carry large quantities of liquid oxygen, and will not have to discard stages of the craft during flight.

It could be what the industry describes as the “Holy Grail” — a single stage to orbit system.

Tuesday, February 27, 2018

Another one from the turn-of-the-century Scientific American – – I can't decide between the Far Side or the Planet of the Apes joke here

This is an interesting piece from a 1907 issue of Scientific American, but what really caught my eye and the reason I'm sharing it with you is that I was under the impression that speculation about animals' problem-solving and tool-building ability was something that scientists first started seriously discussing in the mid-20th century. This account from the generally sober journal shows that the notion was at least considered suitable for serious discussion.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Small improvements

This is Joseph

I hope that this argument is a straw man:

1) Technology is incremental. No one tweak is likely to have a 100% success rate. The modern cell phone is the product of a thousand small tweaks over decades improving efficiency. We did not go from huge analog radios to cell phones in one step.

2) Medical and public health advances are never 100% effective. Vaccines reduce infectious disease but they rarely eliminate it (smallpox being a nice exception). Tactics like hand washing do not drop the rate of disease transmission to zero. Seat belts do not eliminate auto fatalities, even if they reduce them. Josh Marshall is good on this point.

3) Laws reduce risks they do not eliminate them. We have a lot of laws that reduce risks but don;t drop them to zero. We have screeners for airplanes; nobody thinks that they are 100% effective but they are thought to reduce risk. We require people to be licensed to drive not because it drops the rate of accidents to zero but because it reduces the rate.

I mean one could argue that particular guns are important for some reason or another, or that a specific law is bad. But it is the balance between cost and effectiveness -- the effectiveness of a specific intervention may be low but so might the cost. It isn't "virtue signaling" to note that a small improvement in a battery is better, even if it took hundreds of them to make a big difference.

And if we want to make these types of arguments (total benefit is small) then I have an idea for making airports more efficient.

I hope that this argument is a straw man:

Someone will say that mass shooting are rare. Moreover, if a future schoolyard shooter can’t get an AI rifle, he will use an only marginally less lethal weapon. Thus, preventing civilians from legally owning AI rifles would save only a few lives and only trivially reduce the total of gun deaths. So, really, aren’t you just virtue-signalling?Because, if it is serious, it misunderstands technological advances, public health, and legal systems all at once.

1) Technology is incremental. No one tweak is likely to have a 100% success rate. The modern cell phone is the product of a thousand small tweaks over decades improving efficiency. We did not go from huge analog radios to cell phones in one step.

2) Medical and public health advances are never 100% effective. Vaccines reduce infectious disease but they rarely eliminate it (smallpox being a nice exception). Tactics like hand washing do not drop the rate of disease transmission to zero. Seat belts do not eliminate auto fatalities, even if they reduce them. Josh Marshall is good on this point.

3) Laws reduce risks they do not eliminate them. We have a lot of laws that reduce risks but don;t drop them to zero. We have screeners for airplanes; nobody thinks that they are 100% effective but they are thought to reduce risk. We require people to be licensed to drive not because it drops the rate of accidents to zero but because it reduces the rate.

I mean one could argue that particular guns are important for some reason or another, or that a specific law is bad. But it is the balance between cost and effectiveness -- the effectiveness of a specific intervention may be low but so might the cost. It isn't "virtue signaling" to note that a small improvement in a battery is better, even if it took hundreds of them to make a big difference.

And if we want to make these types of arguments (total benefit is small) then I have an idea for making airports more efficient.

Friday, February 23, 2018

I just realized that we haven't made fun of Gwyneth Paltrow for a long time.

Fortunately, Stephen Colbert's staff has been keeping up with goop for us.

Thursday, February 22, 2018

Non-sarcastic praise for Elon Musk (no, really)

This is a big deal. Not as big as some of the hype would lead you to believe and not big in the way most people think, but it is a big deal.

The thing to focus on here is cost. I have seen various estimates and, while evaluating them is well beyond my expertise, if you're looking for a nice round number, 50% seems quite reasonable. We will have to see how reliable the system proves (when your payloads are valued in the billions of dollars, reliability is a major consideration) and will have to see how reusable the reusable boosters are, but at this point it certainly looks like Elon Musk has greatly reduced the cost of getting things into orbit.

This is an extraordinary advance, but it is more an accomplishment of determination then innovation. It is important to note just how mainstream the Falcon Heavy approach is. Most of the basic technology goes back to the Apollo program. This is not, in any way, meant to diminish the exceptional work done by the engineers of SpaceX. Getting this system to work on this scale is incredibly challenging, but it's the kind of challenge that probably could've been done by any number of other major players had they expanded the resources and maintained the focus. Musk does not seem to have shown any interest in radical approaches with even greater potential cost savings such as spaceplanes or railguns and that's not necessarily a bad thing. Both here and with Tesla, Musk has a history of making daring business bets but playing it relatively conservative with the technology. It's an approach with a lot to recommend it (though Tesla investors may not feel that way a year from now – – more on that later).

With so many people out to deify Elon Musk (in the case of the notorious Rolling Stone profile, almost literally), there is an enormous temptation to default to the iconoclastic, but it's important to remember that while Musk may not be the person (and certainly not the engineer) he and his accolades would like you to think he is, the man still has extraordinary gifts for promotion, organization, and motivation, and those gifts sometimes produce some worthwhile, even important benefits.

And, yes, watching those boosters land under their own power is really cool.

Wednesday, February 21, 2018

The stocks “couldn't be valued according to traditional methods because they represented a whole new era of the economy that was nothing like the past.” – Déjà vu all over again

I just finished a recent post on how companies try to get some investor love by associating themselves with sexy, overhyped sectors of the economy. This Forbes piece by Marius Meland nicely illustrates the point.

It's also of interest for a few other reasons. It fits in with our ongoing thread about the technological innovations spikes around the late 19th/early 20th centuries and in the postwar era. The subject of the interview, Burton Malkiel, is possibly the best person you could talk to about market efficiency versus investor irrationality and the timing (a 1999 comparison of the internet boom to previous stock bubbles) makes the observations look particularly prescient in retrospect.

It's also of interest for a few other reasons. It fits in with our ongoing thread about the technological innovations spikes around the late 19th/early 20th centuries and in the postwar era. The subject of the interview, Burton Malkiel, is possibly the best person you could talk to about market efficiency versus investor irrationality and the timing (a 1999 comparison of the internet boom to previous stock bubbles) makes the observations look particularly prescient in retrospect.

"Tronics boom" of 1959-1962

With the dawn of the space age, every electronics stock suddenly took off like a rocket on Wall Street, reaching valuation levels not unlike Internet stocks today. And just like a "dot com" can help an obscure offering surge into the stratosphere today, the key to a stocks success could often be found in its name in the 1960s as well.

"I call it the tronics boom because these soaring stocks usually had some form of tron or tronics in their name," says Malkiel, citing such "trons" as Astron, Dutron, Vulcatron and Transitron and "onics" like Circuitronics, Supronics and Videotronics, as well as one company that, for good measure, put together the winning combination Powertron Ultrasonics.

Then, like now, the demand was huge but the IPOs were relatively thin, so that stock prices would soar at the launch.

Investors argued that "tronics" stocks couldn't be valued according to traditional methods because they represented a whole new era of the economy that was nothing like the past. Promoters entered the stage to talk the stocks up further. As a result, stocks soared to multiples of 50, 100 or even 200 times earnings.

But in late 1962, "tronics" stocks and other growth issues came crashing down in a massive sell-off.

Tuesday, February 20, 2018

More memorable ads from the turn of the century Scientific American

More on the medicinal powers of Coke. 1907

Electricity meant push button control which, if you think about it, was a pretty big deal. 1903

The more things change... 1908

I keep thinking of jokes I shouldn't make. 1903

And from JUNE 10, 1905

From that same issue.

Not all that different from the pitch phone companies make to businesses today. 1908

Electricity meant push button control which, if you think about it, was a pretty big deal. 1903

The more things change... 1908

I keep thinking of jokes I shouldn't make. 1903

And from JUNE 10, 1905

From that same issue.

Not all that different from the pitch phone companies make to businesses today. 1908

Monday, February 19, 2018

Profit laundering

[I need to come back to this in more detail later, but just so it doesn't sit in the queue forever, here's a quick rundown of the concept.]

It's not always rational, but investors care a great deal about where the money comes from. Two companies with exactly the same cost and revenue numbers will often be valued very differently. Sometimes, the preferences are based on perceived possibilities for growth or fears about the future of a particular business or market. Other times, it comes down to the sexiness of the industry and/or the buzz and halo effect surrounding the company.

Obviously, management will do everything it can to put their businesses in the hot category. When a company has multiple sources of revenue of varying attractiveness, it will do its best to maximize the perceived portion of the money coming from the cool streams and minimize the perceived amount coming from the uncool.

We saw some really blatant examples of this in the 90s Internet boom – – companies using brick-and-mortar profits to create the impression of online success – – but it certainly preceded that and it's never gone away since.

The lesson that many investors and most business/financial journalists need to take away from this is that, whenever you have a company with multiple revenue streams, one or more of which is particularly sexy, you should always assume you are being to some degree misled about which stream is actually bringing in the profits.

It's not always rational, but investors care a great deal about where the money comes from. Two companies with exactly the same cost and revenue numbers will often be valued very differently. Sometimes, the preferences are based on perceived possibilities for growth or fears about the future of a particular business or market. Other times, it comes down to the sexiness of the industry and/or the buzz and halo effect surrounding the company.

Obviously, management will do everything it can to put their businesses in the hot category. When a company has multiple sources of revenue of varying attractiveness, it will do its best to maximize the perceived portion of the money coming from the cool streams and minimize the perceived amount coming from the uncool.

We saw some really blatant examples of this in the 90s Internet boom – – companies using brick-and-mortar profits to create the impression of online success – – but it certainly preceded that and it's never gone away since.

The lesson that many investors and most business/financial journalists need to take away from this is that, whenever you have a company with multiple revenue streams, one or more of which is particularly sexy, you should always assume you are being to some degree misled about which stream is actually bringing in the profits.

Friday, February 16, 2018

Alec Guinness was George Smiley

If you can think of a piece of video, be it an old TV show, a musical performance, a stand-up routine, it's probably on YouTube. I've started making a note whenever I think of something I'd like to see (or see again), like this definitive adaptation of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy...

And of Smiley's People.

And of Smiley's People.

Thursday, February 15, 2018

Of course, modern researchers tried talking to plants so who are we to judge?

I'd never heard of electro-culture before coming across this article from a turn-of-the-century issue of Scientific American, but, based on some quick googling, it seems to have been one of those scientific theories (like N-rays and, to a lesser extent, Martian canals) that had a brief run of acceptance and respectability before being dismissed by the scientific community and drifting into the area of fringe beliefs.

The big question reading this today is whether or not the original researchers were frauds or simply incompetence who did a bad job setting up their experiments.

The cover of the issue, depicting Russian battleships, has nothing to do with this article but it's too cool to leave out.

The big question reading this today is whether or not the original researchers were frauds or simply incompetence who did a bad job setting up their experiments.

The cover of the issue, depicting Russian battleships, has nothing to do with this article but it's too cool to leave out.

Tech Boosterism

[More notes for the upcoming book]

Journalists have a natural tendency to be supportive of efforts to serve some public good. There is undoubtedly an element of self-interest here – – philanthropists and local heroes make for good copy – – but I suspect of main driver is a sincere desire to advance worthwhile causes. This is completely understandable and even, to some degree, praiseworthy, but it can also be dangerous.

Accounts of volunteers cleaning seabirds after an oil spill can create a false sense of having addressed a massive problem. Feel-good stories about imaginative school fundraising projects (disproportionately found in relatively wealthy districts) seldom mention the ways that funding by community can exacerbate educational inequality. Press releases on hedge fund managers always omit the tax benefits, the strings that often accompanied the gifts, and the reputation laundering bought with what is frequently very dirty money (see the Sacklers and the opioid crisis for example).

The damage caused by uncritical and unthinking supportive journalism really kicks into high gear when you combine it with other biases and corrupting factors. This problem is particularly acute with technology. Most journalists quite reasonably see technological progress as being good for society on the whole. Therefore, the default setting of a report of some demonstration or new development is "isn't that great?".

Unfortunately, this default approach is generally combined with a weak grasp of how technology works and progresses, particularly when it comes to things like proposals, prototypes, and producing viable products. Add to that the tremendous role of hype, the enthusiasm for conventional narratives (in this case frequently involving Silicon Valley messiahs, often with what can only be described as magical powers -- see magical heuristics), and the occasional flat out scam. The result is a press corps that ranges from a mainstream that is strongly inclined to believe what they're told to converts with a cultlike faith in Elon Musk and company.

Journalists have a natural tendency to be supportive of efforts to serve some public good. There is undoubtedly an element of self-interest here – – philanthropists and local heroes make for good copy – – but I suspect of main driver is a sincere desire to advance worthwhile causes. This is completely understandable and even, to some degree, praiseworthy, but it can also be dangerous.

Accounts of volunteers cleaning seabirds after an oil spill can create a false sense of having addressed a massive problem. Feel-good stories about imaginative school fundraising projects (disproportionately found in relatively wealthy districts) seldom mention the ways that funding by community can exacerbate educational inequality. Press releases on hedge fund managers always omit the tax benefits, the strings that often accompanied the gifts, and the reputation laundering bought with what is frequently very dirty money (see the Sacklers and the opioid crisis for example).

The damage caused by uncritical and unthinking supportive journalism really kicks into high gear when you combine it with other biases and corrupting factors. This problem is particularly acute with technology. Most journalists quite reasonably see technological progress as being good for society on the whole. Therefore, the default setting of a report of some demonstration or new development is "isn't that great?".

Unfortunately, this default approach is generally combined with a weak grasp of how technology works and progresses, particularly when it comes to things like proposals, prototypes, and producing viable products. Add to that the tremendous role of hype, the enthusiasm for conventional narratives (in this case frequently involving Silicon Valley messiahs, often with what can only be described as magical powers -- see magical heuristics), and the occasional flat out scam. The result is a press corps that ranges from a mainstream that is strongly inclined to believe what they're told to converts with a cultlike faith in Elon Musk and company.

Wednesday, February 14, 2018

Keep in mind that back then $600 million was quite a bit of money

Tuesday, February 13, 2018

“I’m almost afraid not to take the chance,” – This is when it becomes a bubble.

It's that moment when risk aversion flips and the thought of not making money starts to feel like losing it. I'm not talking about opportunity costs in any kind of rational sense. Instead, I'm referring to having the visceral emotional reaction associated with a deep, costly loss because you didn't buy into the skyrocketing market the day before. People become afraid not to invest in what should obviously be highly risky ventures.

Truly crazy bubbles are driven by this paradoxical combination of greed and fear. They both desire instant wealth and dread the sense of regret that would go with missing it. Individually, either of these emotions can drive otherwise sensible people into irrational behavior. Together, they can spur investment in some laughably bad ideas.

This Washington Post piece by Chico Harlan on a group of Bitcoin investors perfectly illustrates the point.

“Us little guys working our butts off, we can’t get ahead,” Cedric Knight, 35, told Melin. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change my life.”

Knight and others visiting Melin were pinning their hopes on a new form of currency whose potential value the world was only beginning to recognize. Millions of people around the world are chasing after fortune by investing in bitcoin — which has soared by more than 2,500 percent in value in the past two years — and other digital instruments known as cryptocurrencies.

...

“What crypto allows is for the masses to be venture capitalists,” Melin said.

“And guys like me, I’m not in the loop,” Knight said. “This is my chance.”

…

Knight, meantime, went home, cooked dinner and then decided to reopen one of the eight cryptocurrency apps he had downloaded. His account had fallen nearly $500 on the day — his initial $1,500 was below $900 — and he said he was “freaking out.” But then, he thought about what it meant to be a cryptocurrency investor. There would be days such as this. But there might be better days, too — much better days. If there were, he did not want to miss out.

“I’m almost afraid not to take the chance,” he said, and soon, he added $260 to his cryptocurrency account.

Some historical perspective from the archives.

"A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is."

Another except from Charles Mackay's Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. I believe "a company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is" was an initial business plan for Groupon.Some of these schemes were plausible enough, and, had they been undertaken at a time when the public mind was unexcited, might have been pursued with advantage to all concerned. But they were established merely with the view of raising the shares in the market. The projectors took the first opportunity of a rise to sell out, and next morning the scheme was at an end. Maitland, in his History of London, gravely informs us, that one of the projects which received great encouragement, was for the establishment of a company "to make deal-boards out of saw-dust." This is, no doubt, intended as a joke; but there is abundance of evidence to show that dozens of schemes hardly a whir more reasonable, lived their little day, ruining hundreds ere they fell. One of them was for a wheel for perpetual motion—capital, one million; another was "for encouraging the breed of horses in England, and improving of glebe and church lands, and repairing and rebuilding parsonage and vicarage houses." Why the clergy, who were so mainly interested in the latter clause, should have taken so much interest in the first, is only to be explained on the supposition that the scheme was projected by a knot of the foxhunting parsons, once so common in England. The shares of this company were rapidly subscribed for. But the most absurd and preposterous of all, and which showed, more completely than any other, the utter madness of the people, was one, started by an unknown adventurer, entitled "company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is." Were not the fact stated by scores of credible witnesses, it would be impossible to believe that any person could have been duped by such a project. The man of genius who essayed this bold and successful inroad upon public credulity, merely stated in his prospectus that the required capital was half a million, in five thousand shares of 100 pounds each, deposit 2 pounds per share. Each subscriber, paying his deposit, would be entitled to 100 pounds per annum per share. How this immense profit was to be obtained, he did not condescend to inform them at that time, but promised, that in a month full particulars should be duly announced, and a call made for the remaining 98 pounds of the subscription. Next morning, at nine o'clock, this great man opened an office in Cornhill. Crowds of people beset his door, and when he shut up at three o'clock, he found that no less than one thousand shares had been subscribed for, and the deposits paid. He was thus, in five hours, the winner of 2,000 pounds. He was philosopher enough to be contented with his venture, and set off the same evening for the Continent. He was never heard of again

Monday, February 12, 2018

Laws and markets

This is Joseph

This point, by James Joyner, is quite good:

But all markets are based on rules and laws. We would have no markets at all if force and fraud where not prohibited, for example. The piece that is dodgy here is the evasion of the existing rules in order to build a company. It is fine to lobby to change the rules. But when you have to design your business to evade local regulations then that is a problem. Not because the laws are good -- they are likely not. But because it is not the case that private actors who violate laws that they see as stifling innovation are left alone.

And if government is wrong about a law and needs to backtrack then it makes sense to compensate the losers of the law change. We don't let private property block roads but we do have to buy it back when we put a road in. I think applying the same logic to shutting down taxi licensing agreements is sensible.

This point, by James Joyner, is quite good:

The taxi industry is a special case, though, in that cab and limousine owners and drivers made economic decisions based on rules set by the government. While the medallion system is outrageous and I’m happy to see it disrupted, the fact of the matter is that it was the norm for generations. People saved up or took big risks in borrowing to bid on them based on guarantees from their municipal government. They have every right to expect that same government to either enforce the law against illegal competition or compensate them in some way for the broken contract.The piece that is very important here is the decision to change the legal framework. Disruption is normal and many people end up as economic losers when conditions change. We are already bad at coping with that.

But all markets are based on rules and laws. We would have no markets at all if force and fraud where not prohibited, for example. The piece that is dodgy here is the evasion of the existing rules in order to build a company. It is fine to lobby to change the rules. But when you have to design your business to evade local regulations then that is a problem. Not because the laws are good -- they are likely not. But because it is not the case that private actors who violate laws that they see as stifling innovation are left alone.

And if government is wrong about a law and needs to backtrack then it makes sense to compensate the losers of the law change. We don't let private property block roads but we do have to buy it back when we put a road in. I think applying the same logic to shutting down taxi licensing agreements is sensible.

Friday, February 9, 2018

The Snow Bicycle -- wonder why this never caught on

People at the turn of the century were fascinated by the bicycle, both as a practical form of transportation and as a sport. Being an age of great inventiveness, lots of variations were tried, some more viable than others.

I've been working on a project involving not only the technological explosion of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries (which introduced the huge hit Daisy Bell)...

... but also the post-war period (where the still remembered Daisy Bell would provide and interesting footnote).

Which inspired...

I've been working on a project involving not only the technological explosion of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries (which introduced the huge hit Daisy Bell)...

... but also the post-war period (where the still remembered Daisy Bell would provide and interesting footnote).

Which inspired...

Thursday, February 8, 2018

That New York Times piece on Tesla was even worse than I thought.

In case you missed part one,a few days ago, I took John F. Wasik and the New York Times to task for a piece that attempted to mythologize Nikola Tesla by distorting the historical record and omitting a number of pertinent facts. One passage I jumped on somewhat vigorously was the following.

Tesla proposed the development of torpedoes well before World War I. These weapons eventually emerged in another form — launched from submarines.

I pointed out that there was no way Tesla could have "proposed" the development of torpedoes in the late 1890s since the Whitehead self-propelled torpedo had been in use for decades and had already revolutionized naval warfare. What I failed to catch was just how off the second sentence was. I knew that the "eventually" was stretching it, but I didn't realize that it wasn't even directionally accurate.

Submarines were another line of technology that made revolutionary leaps due to advances in internal combustion and electricity. It turns out that there were a number of torpedo-firing subs being tested and even, to a limited extent, deployed by the time that Tesla demonstrated his torpedo. We can probably dismiss the first submarine to fire a torpedo while submerged (way back in 1886) as a failed experiment, but by the late 1890s, viable models were in the water, most notably the USS Holland which established most of the main features (albeit in a simplified form) of submarines until the advent of nuclear power.

[In addition to torpedoes, the boat was armed with a pneumatic dynamite gun seen here.]

I realize I'm piling on, but there's a lot of wrong here, and seeing the facts so badly mangled in the New York Times, a publication that prides itself on fact checking, raises serious questions. I'd offer a couple of possible explanations. First, I suspect a great deal of the push for accuracy is driven by fear of how subjects might react. Writing about people long dead takes a certain amount of the pressure off.

Second, and I think more important, the lone, misunderstood visionary is a popular and reassuring conventional narrative. It tells a good story and it makes us feel superior to the people of Tesla's time (we, being sophisticated and having a deep understanding of technology, would have immediately seen the potential of these ideas). Lord Keynes famously said “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” The journalistic corollary of that is that standards are lower if you stick to conventional narratives and approved memes. Alessandra Stanley can prompt corrections that threaten to go on longer than the original articles. Maureen Dowd can babble incoherently about Washington dinner party gossip. David Brooks can simply make shit up. It's all okay because they are telling familiar stories that the establishment is comfortable with. The knives only come out for independent thought.

Wednesday, February 7, 2018

“One of the most powerful influences for broadening human intelligence… has spread an even, highly developed civilization through the land… has unified the Nation.”

From an AT&T advertisement that ran in Scientific American. June 19th, 1909.

Even allowing for the inevitable hyperbole of ad copy, this is big talk, but it is highly indicative of its era. There was a widespread, perhaps even dominant belief among turn-of-the-century Americans that the generation of unprecedented technological progress they had just witnessed marked the beginning of a new age of civilization and perhaps even human evolution.

This was about the time that the idea of and unimaginable future coming at us with ever-increasing speed first took hold in the public consciousness. It was also perhaps the last time events justified the notion.

Even allowing for the inevitable hyperbole of ad copy, this is big talk, but it is highly indicative of its era. There was a widespread, perhaps even dominant belief among turn-of-the-century Americans that the generation of unprecedented technological progress they had just witnessed marked the beginning of a new age of civilization and perhaps even human evolution.

This was about the time that the idea of and unimaginable future coming at us with ever-increasing speed first took hold in the public consciousness. It was also perhaps the last time events justified the notion.

Tuesday, February 6, 2018

"It’s not just the Second Avenue Subway"

Over at Citylab, Alon Levy has a great piece on the costs of passenger rail.

The approximate range of underground rail construction costs in continental Europe and Japan is between $100 million per mile, at the lowest end, and $1 billion at the highest. Most subway lines cluster in the range of $200 million to $500 million per mile; in Amsterdam, a six-mile subway line cost 3.1 billion Euros, or about $4 billion, after severe cost overruns, delays, and damage to nearby buildings. The Second Avenue Subway is unique even in the U.S. for its exceptionally high cost, but elsewhere, the picture is grim by European standards:

It is hard to find exact international comparisons for subway lines running in the medians of freeways. However, it should not be much more difficult to construct such lines than to build light rail. Indeed, in the study for Atlanta’s I-20 East extension, there are options for light rail and bus rapid transit, and the light rail option is only slightly cheaper than the heavy rail option, at $140 million per mile.

Line Type Cost Length Cost/mile San Francisco Central Subway Underground $1.57 billion 1.7 miles $920 million Los Angeles Regional Connector Underground $1.75 billion 1.9 miles $920 million Los Angeles Purple Line Phases 1-2 Underground $5.2 billion 6.5 miles $800 million BART to San Jose (proposed) 83% Underground $4.7 billion 6 miles $780 million Seattle U-Link Underground $1.8 billion 3 miles $600 million Honolulu Area Rapid Transit Elevated $10 billion 20 miles $500 million Boston Green Line Extension Trench $2.3 billion 4.7 miles $490 million Washington Metro Silver Line Phase 2 Freeway median $2.8 billion 11.5 miles $240 million Atlanta I-20 East Heavy Rail Freeway median $3.2 billion 19.2 miles $170 million

Lists of light-rail lines built in France in recent years can be found on French Wikipedia and Yonah Freemark’s The Transport Politic, and in articles in French media. The cheaper lines cost about $40 million per mile, the more expensive ones about $100 million.

In the United States, most recent and in-progress light-rail lines cost more than $100 million per mile. Two light-rail extensions in Minneapolis, the Blue Line Extension and the Southwest LRT, cost $120 million and $130 million per mile, respectively. Dallas’ Orange Line light rail, 14 miles long, cost somewhere between $1.3 billion and $1.8 billion. Portland’s Orange Line cost about $200 million per mile. Houston’s Green and Purple Lines together cost $1.3 billion for about 10 miles of light rail.

Monday, February 5, 2018

This is almost beyond parody

This is Joseph

From Duncan Black, we have this article:

Second, there is a huge implicit road subsidy here for these companies, presuming non-AVs would need to be banned as well. Roads that can only be used by corporations (not individuals) that appear to be supported by public taxation.

Three, doesn't this create perverse incentives to make public transportation less effective, via lobbying for weaker bus service, especially if AVs become more standard?

Four, isn't regulation intended to give private benefit to a public good a problem? Allowing an AV to only be operated by a collective seems to be an odd regulation. In what other area do we restrict items to use by corporations but ban private use? There must be some but . . .

Five, doesn't this likely end up with more non-AVs on the road, making the AVs less safe because they can't communicate with non-AVs?

It seems like a very self-serving idea as a ride sharing fleet. I am curious what benefits we have here that wouldn't apply to public transit?

From Duncan Black, we have this article:

And today, a coalition of companies—including Lyft, Uber, and Zipcar—officially announced that they were signing on to a 10-point set of “shared mobility principles for livable cities”—in other words, industry goals for making city transit infrastructure as pleasant, equitable, and clean as possible. Some of the 10 statements, like “we support people over vehicles,” are vague but positive. But the final one speaks loudly about what city roads of the future could look like: “that autonomous vehicles (AVs) in dense urban areas should be operated only in shared fleets.”

It’s a “very convenient” idea for the companies who are promoting it, says Don MacKenzie, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington. “It is basically [tying] the success of these companies to the adoption of autonomous vehicles,” he says. In other words, putting this principle in action means that “if people want the benefits of AVs, they can only get that by using shared fleets.” (Worth noting that the concept only applies to dense urban areas.)Ok, the first thing here is that any possible argument for this approach for AVs is going to apply to public transit as well. Bus service would be greatly improved if many or most cars were banned or restricted from operation on city streets.

Second, there is a huge implicit road subsidy here for these companies, presuming non-AVs would need to be banned as well. Roads that can only be used by corporations (not individuals) that appear to be supported by public taxation.

Three, doesn't this create perverse incentives to make public transportation less effective, via lobbying for weaker bus service, especially if AVs become more standard?

Four, isn't regulation intended to give private benefit to a public good a problem? Allowing an AV to only be operated by a collective seems to be an odd regulation. In what other area do we restrict items to use by corporations but ban private use? There must be some but . . .

Five, doesn't this likely end up with more non-AVs on the road, making the AVs less safe because they can't communicate with non-AVs?

It seems like a very self-serving idea as a ride sharing fleet. I am curious what benefits we have here that wouldn't apply to public transit?

Friday, February 2, 2018

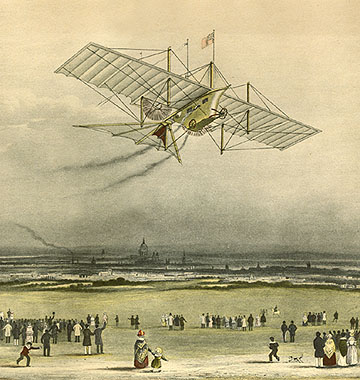

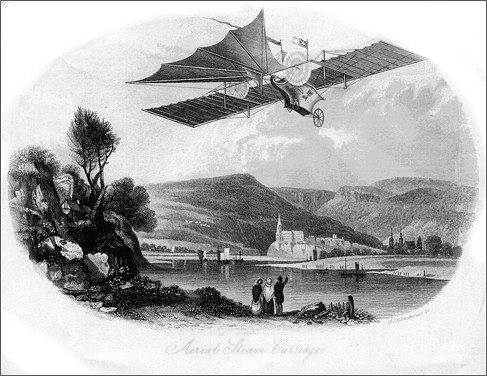

I think Uber might be using the hover-plane design for its proposed flying taxis.

As we mentioned before, fairly early in the 20th century, popular culture seem to have settled on the period roughly around 1890 as the end of the simple, leisurely-paced good old days, just before technological revolution sent the country hurtling into the future.

Just Imagine is a good example if not a good film (to be perfectly honest, I've never made it all the way through without skipping sizable chunks). The period of comparison is pushed back to 1880 – – probably in order to have a nice round hundred years before the main action set in 1980 – – but the rest of the formula is there.

El (short for Elmer) Brendel was a popular Swedish dialect comedian who was popular at the time (though not popular enough for either of his starring vehicles to turn a profit). These days he is remembered almost solely for this film which itself is remembered mainly for providing stock footage for Saturday morning serials like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers.

It's worth checking out the first few minutes just for the art direction and then fast forwarding to around the 22 minute mark where Henry Ford's anti-Semitism provides the subject for a then topical joke.

Just Imagine is a good example if not a good film (to be perfectly honest, I've never made it all the way through without skipping sizable chunks). The period of comparison is pushed back to 1880 – – probably in order to have a nice round hundred years before the main action set in 1980 – – but the rest of the formula is there.

El (short for Elmer) Brendel was a popular Swedish dialect comedian who was popular at the time (though not popular enough for either of his starring vehicles to turn a profit). These days he is remembered almost solely for this film which itself is remembered mainly for providing stock footage for Saturday morning serials like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers.

It's worth checking out the first few minutes just for the art direction and then fast forwarding to around the 22 minute mark where Henry Ford's anti-Semitism provides the subject for a then topical joke.

Thursday, February 1, 2018

Media Post: Game of Thrones and succession

This is Joseph

** SPOILERS**

As some readers may know, the TV show game of thrones has bypassed the book series a song of ice and fire by George RR Martin. In the process, they have also appeared to merge a number of characters together, to reduce complexity. In the process, however, they have undermined a key piece of the entire story.

The plot that starts the whole series off is the discovery that the children of Cersei Lannister are not the real children of the king, Robert Baratheon. As a result, they lack a blood claim to the iron throne. In parallel, we have the story of Daenerys Targaryen who is seeking to reclaim the iron throne because she is a relative of the deposed king. We also have a history of a rebellion where the king was overthrown and replaced by a relative (said Robert) who had a close blood claim on the throne. Finally. there is a hidden twist where the bastard son of Ned Stark, Jon Snow, is actually the legitimate son of the Targaryen prince and has a stronger claim to the throne than Daenerys.

So the whole plot is driven by blood claims and how they influence character's succession rights. It is also a medieval world and not a modern one -- the king needs the support of the nobles in order to raises armies and funds. These nobles, themselves, depend on succession for legitimacy.

In the last season there were some questionable succession moves. But for some of them I can justify how the claim comes into being. Cersei Lannister is a close relative (mother) of the last king and happens to be in charge of the regency at the time. It's not typical, but it happened with Catherine the Great (for example) where a marriage/parentage claim allowed an unexpected monarch. Same with the Queen of Thorns -- she is at least a close relative of the last head of house Tyrell. An odd succession choice but you can see how she could have been a compromise candidate.

But what is going on with Ellaria Sand? She leads a coup to kill the members of the ruling family of Dorne. She is the illegitimate girlfriend of the brother of the previous ruler. How does she end up in charge? Now I could imagine a sand snake in charge -- they are also illegitimate but are at least the daughters of Oberyn Martell. But Ellaria?

Ellaria then joins forces with Daenerys, whose only legitimate claim on the iron throne rests on blood succession. If you take that away then you have a foreign invader pursuing a grudge against the family of people who wronged her (it is obvious that Cersei, herself, had nothing to do with Robert's Rebellion and the major rebels are all dead).

Why would Daenerys undermine the major point in her favor (succession law) by allying with somebody who has no succession rights to her current position (inside her kingdom) and, at the very least, was suspiciously involved with the violent death of the previous ruler and heir. I mean both were cut down along with their bodyguard -- nobody is dumb enough to think that this is an accident.

What I think happened was that they merged Arianne Martel with Ellaria. If Arianne did this plot then that would be different. Without clear evidence that she was the murderer then she has the best claim to the throne (being the current heir). Ambiguity might preserve her position (think of Edward II and Edward III) and objectors would have to act fast to gather evidence. Nobles wouldn't see their succession rights being tainted.

But this adaption definitely requires some more thought and should have been staged better. Why not put Obara Sand in charge, as the closet blood relative to the now extinct house of Martell? It might not be extinct in the books, but at least in the show that would be an easy claim to make as they killed every Martell we met. As it is, without additional information, the succession of Ellaria Sand to the leadership of Dorne undermines the main force driving the political plot and reduces the coherence of the story.

This was not one of the changes that improved the show.

** SPOILERS**

As some readers may know, the TV show game of thrones has bypassed the book series a song of ice and fire by George RR Martin. In the process, they have also appeared to merge a number of characters together, to reduce complexity. In the process, however, they have undermined a key piece of the entire story.

The plot that starts the whole series off is the discovery that the children of Cersei Lannister are not the real children of the king, Robert Baratheon. As a result, they lack a blood claim to the iron throne. In parallel, we have the story of Daenerys Targaryen who is seeking to reclaim the iron throne because she is a relative of the deposed king. We also have a history of a rebellion where the king was overthrown and replaced by a relative (said Robert) who had a close blood claim on the throne. Finally. there is a hidden twist where the bastard son of Ned Stark, Jon Snow, is actually the legitimate son of the Targaryen prince and has a stronger claim to the throne than Daenerys.

So the whole plot is driven by blood claims and how they influence character's succession rights. It is also a medieval world and not a modern one -- the king needs the support of the nobles in order to raises armies and funds. These nobles, themselves, depend on succession for legitimacy.

In the last season there were some questionable succession moves. But for some of them I can justify how the claim comes into being. Cersei Lannister is a close relative (mother) of the last king and happens to be in charge of the regency at the time. It's not typical, but it happened with Catherine the Great (for example) where a marriage/parentage claim allowed an unexpected monarch. Same with the Queen of Thorns -- she is at least a close relative of the last head of house Tyrell. An odd succession choice but you can see how she could have been a compromise candidate.

But what is going on with Ellaria Sand? She leads a coup to kill the members of the ruling family of Dorne. She is the illegitimate girlfriend of the brother of the previous ruler. How does she end up in charge? Now I could imagine a sand snake in charge -- they are also illegitimate but are at least the daughters of Oberyn Martell. But Ellaria?

Ellaria then joins forces with Daenerys, whose only legitimate claim on the iron throne rests on blood succession. If you take that away then you have a foreign invader pursuing a grudge against the family of people who wronged her (it is obvious that Cersei, herself, had nothing to do with Robert's Rebellion and the major rebels are all dead).

Why would Daenerys undermine the major point in her favor (succession law) by allying with somebody who has no succession rights to her current position (inside her kingdom) and, at the very least, was suspiciously involved with the violent death of the previous ruler and heir. I mean both were cut down along with their bodyguard -- nobody is dumb enough to think that this is an accident.

What I think happened was that they merged Arianne Martel with Ellaria. If Arianne did this plot then that would be different. Without clear evidence that she was the murderer then she has the best claim to the throne (being the current heir). Ambiguity might preserve her position (think of Edward II and Edward III) and objectors would have to act fast to gather evidence. Nobles wouldn't see their succession rights being tainted.

But this adaption definitely requires some more thought and should have been staged better. Why not put Obara Sand in charge, as the closet blood relative to the now extinct house of Martell? It might not be extinct in the books, but at least in the show that would be an easy claim to make as they killed every Martell we met. As it is, without additional information, the succession of Ellaria Sand to the leadership of Dorne undermines the main force driving the political plot and reduces the coherence of the story.

This was not one of the changes that improved the show.

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

Alon vs. Elon

Alon Levy is a highly respect transportation blogger currently based in Paris. He's also perhaps the leading debunker of the Hyperloop (or more accurately, the “Hyperloop,” but that's a topic we've probably exhausted). When Brad Plumer writing in the Washington Post declared ‘There is no redeeming feature of the Hyperloop.’, the headline was a quote from Levy.

Recently, Levy took a close look at Musk's Boring Company and found the name remarkably apt. We'd previously expressed skepticism about Musk's claim, but it turns out we were being way too kind.

Levy's takedown is detailed but readable and I highly recommend going through it if you have any interest in what drives infrastructure costs. Rather than try to excerpt some of the more technical passages, I thought I'd stick with the following general but still sharp observation from the post.

Recently, Levy took a close look at Musk's Boring Company and found the name remarkably apt. We'd previously expressed skepticism about Musk's claim, but it turns out we were being way too kind.

Levy's takedown is detailed but readable and I highly recommend going through it if you have any interest in what drives infrastructure costs. Rather than try to excerpt some of the more technical passages, I thought I'd stick with the following general but still sharp observation from the post.