Wednesday, November 22, 2017

Igon values, superstar coin flippers, and the Gladwell problem

Malcolm Gladwell has started coming up in quite a few major threads and

larger pieces, so I decided I needed to get up to speed on some of the

controversies involving the author. Some of the more substantial have centered around what Steven Pinker has called the Igon value problem

From Pinker's

review of "What the Dog Saw"

An eclectic essayist is necessarily a dilettante, which is not in itself

a bad thing. But Gladwell frequently holds forth about statistics and

psychology, and his lack of technical grounding in these subjects can be

jarring. He provides misleading definitions of “homology,” “sagittal

plane” and “power law” and quotes an expert speaking about an “igon

value” (that’s eigenvalue, a basic concept in linear algebra). In the

spirit of Gladwell, who likes to give portentous names to his aperçus, I

will call this the Igon Value Problem: when a writer’s education on a

topic consists in interviewing an expert, he is apt to offer

generalizations that are banal, obtuse or flat wrong.

Gladwell got the best of the follow up exchange, dismissing

“igon value” as a spelling error while getting Pinker sucked into a

bunch of secondary or even tertiary arguments. (One of the best

indicators of intelligence is the ability to avoid discussions about the

heritability of intelligence.)

The spelling error defense is

technically correct but it misrepresents the main point of the

criticism. First off, on a really basic level, this indicates poor fact

checking on the part of Mr. Gladwell and the New Yorker. Even working

under the relatively low standards of the blogosphere, I always try to

Google unfamiliar phrases before quoting them. You'd think that the

editors of America's most distinguished magazine would do at least that

much.

More importantly, spelling errors fall in two basic

categories. The first does not tell us anything substanitive about the

writer. Given the ghoti insanity of the English language, being a bad

speller does not necessarily imply a weak vocabulary or poor mastery of

the language (put another way, not knowing whether it's double C or

double S in "necessarily"does not necessarily suggest that you don't

know what "necessarily" means). There are, however, cases (particularly

involving transcription) where spelling errors can indicate that the

writer is unfamiliar with the words in question. That appears to be the

case here.

Pinker's central criticism largely boils down to

phonetic reporting. Gladwell often goes into stories with a weak grasp

of the field in question, as a result he frequently makes serious

mistakes, constantly misses important subtleties, and is almost

completely dependent on his subjects for understanding and context. Add

to this poor fact checking and a disturbing nonchalance about getting

the story right, and things can get ugly quickly.

Somewhat

ironically, Gladwell hit back at Pinker for employing one of the same

techniques which Gladwell is so proud of, picking a detail that told a

good story and memorably illustrated a larger idea. The Igon Value

Problem worked beautifully on those terms but it was far from the most

serious or conclusive example available, even if we limit ourselves to

the single article in question, "Blowing Up."

For example, the

piece is very much invested in the idea of Taleb as Wall Street

revolutionary. We could quibble about just how radical the Black Swan

ideas and strategies are, but it is an entirely defensible

interpretation. Unfortunately, Gladwell doesn't really understand which

ideas are debatably new and which are familiar to anyone in finance.

Here's an

excerpt (starting and ending mid-paragraph):

There was just one problem, however, and it is the key to understanding

the strange path that Nassim Taleb has chosen, and the position he now

holds as Wall Street's principal dissident. Despite his envy and

admiration, he did not want to be Victor Niederhoffer -- not then, not

now, and not even for a moment in between. For when he looked around

him, at the books and the tennis court and the folk art on the walls --

when he contemplated the countless millions that Niederhoffer had made

over the years -- he could not escape the thought that it might all have

been the result of sheer, dumb luck.

Taleb knew how heretical

that thought was. Wall Street was dedicated to the principle that when

it came to playing the markets there was such a thing as expertise, that

skill and insight mattered in investing just as skill and insight

mattered in surgery and golf and flying fighter jets.

...

For

Taleb, then, the question why someone was a success in the financial

marketplace was vexing. Taleb could do the arithmetic in his head.

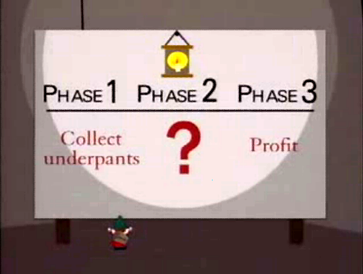

Suppose that there were ten thousand investment managers out there,

which is not an outlandish number, and that every year half of them,

entirely by chance, made money and half of them, entirely by chance,

lost money. And suppose that every year the losers were tossed out, and

the game replayed with those who remained. At the end of five years,

there would be three hundred and thirteen people who had made money in

every one of those years, and after ten years there would be nine people

who had made money every single year in a row, all out of pure luck.

But of course, Taleb didn't have to "do the arithmetic in his head"

because, like virtually everyone else on Wall Street, he had probably

read almost the same analogy in a famous passage from A Random Walk Down

Wall Street by Burton Malkiel [transcribed via Dragon so beware of

homonyms]:

Perhaps the laws of chance should be illustrated. Let's engage in a coin

flipping contest. Those who can consistently flip heads will be

declared winners. The contest begins and 1,000 contestants flip coins.

Just as would be expected by chance, 500 of them flip heads and these

winners are allowed to advance to the second stage of the contest and

flip again. As might be expected, 250 flip heads. Operating under the

laws of chance, there will be 125 winners in the third round, the three

in the fourth, 31 in the fifth, 16 in the sixth, and 8 in the seventh.

By

this time, crowds start to gather to witness the surprising ability of

these expert coin-flippers. The winners are overwhelmed with adulation.

They are celebrated as geniuses in the art of coin-flipping, their

biographies are written, and people urgently seek their advice. After

all, there were 1000 contestants and only eight could consistently flip

heads. The game continues and some contestants eventually flip heads

nine and ten times in a row. [* If we had let the losers continue to

play (as mutual fund managers do, even after a bad year), we would have

found several more contestants who flipped eight or nine ads out of 10

and were therefore regarded as expert coin-flippers.] The point of this

analogy is not to indicate that investment-fund managers can or should

make their decisions by flipping coins, but that the laws of chance do

operate and that they can explain some amazing success stories.

(I love that second paragraph. Pretty much any time I flip past CNBC it comes flooding back to mind.)

Malkiel

published this book in 1973 and though it more than ruffled a few

feathers, it quickly became one of the seminal books on investing.

Malcolm Gladwell's New Yorker piece came out 25 years later.

None

of this is meant to imply any kind of deliberate plagiarism. Quite the

opposite. I very much doubt that Gladwell realized he was paraphrasing a

well-known passage. What I strongly suspect happened was that Taleb

cited this in an interview as a standard example that everyone would be

familiar with, sort of like describing a situation as a "frog in boiling

water."

Gladwell's unacknowledged paraphrase is yet another

indication that he didn't understand the strange role that economic

theory and particularly market efficiency (in this case the semi-strong

variety) plays on Wall Street, a role that was central to his narrative.

This would be bad enough if he was just shooting for a straightforward

profile, but Gladwell insists on playing the deep thinker, making

pseudo-profound points, even closing with a grand sweeping moral about

human nobility:

“That is the lesson of Taleb and Niederhoffer, and also the lesson of

our volatile times. There is more courage and heroism in defying the

human impulse, in taking the purposeful and painful steps to prepare for

the unimaginable.”

Gladwell loves to tell what Christopher Chabris has

termed

"just-so stories," cute little fables counterintuitive and surprising

enough to catch the eye but neat and simple enough to go down easy.

Paradoxically, pulling off that sort of simplicity requires that the

writer have a deep and subtle understanding of his or her subject.

Simplifying a subject you don't understand never goes well.