This Is Spinal Tap star Harry Shearer is suing Universal parent Vivendi for what he alleges is dramatic and deliberate under-payment of music royalties from the classic spoof rockumentary.

In a lawsuit filed at the Central District Court of California yesterday (October 17), Shearer accuses Vivendi of “fraudulent accounting for revenues from music copyrights” – through Universal – as well as mismanaging film and merchandising rights through UMG sister companies such as StudioCanal.

Shearer co-created the film, co-wrote the soundtrack and starred as the Spinal Tap band’s bassist, Derek Smalls.

He claims that between 1989 and 2006, total income from soundtrack music sales for the four creators of the film was reported by Vivendi as just $98. (Yes, ninety-eight dollars.)

In addition, he claims that Vivendi ‘asserts that the four creators’ share of total worldwide merchandising income between 1984 and 2006 was $81’.

...

“Vivendi and its subsidiaries – which own the rights to thousands and thousands of creative works – have, at least in our case, conducted blatantly unfair business practices,” Shearer continued.

“But I wouldn’t be surprised if our example were the tip of the iceberg. Though I’ve launched this lawsuit on my own, it is in reality a challenge to the company on behalf of all creators of popular films whose talent has not been fairly remunerated.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

Vivendi, where the shamelessness goes to 11

Via Mark Evanier, we have yet another reminder that, while Hollywood has always leaned toward the evil, executives for the massive mass media conglomerates/walking anti-trust violations are determined to keep pushing the envelope.

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

A mean looking kid walking by a row of glass houses with a big ol' bag of rocks -- repost

[The nomination of Donald Trump was made possible by numerous failures of the news media to do its job. Therefore it is useful to look back at how things got this bad. Here's a post we did in 2013 (almost exactly three years ago) where we talked about how Paul Krugman, who would be, by far, the paper's most prescient voice in 2016, was dismissed as a loose cannon by the NYT.]

TPM has a short but fascinating revelation

As regulars have probably guessed, I see this as another result of an increasingly dysfunctional culture of journalism, specifically the way that journalists react to having someone on the inside who ignores the implicit code of conduct.

This is not a left/right matter -- it cuts across pretty much all of the media establishment -- but conservatives have tended to make better tactical use of the rules we're talking about, for instance, using pox-on-both-their-houses conventions to provide cover for unpopular positions. As a result, there are more obvious targets on the right but that's a fairly trivial factor.

Silver and Krugman prompted such a strong reaction not because they were too liberal (despite seeing the world through an overwhelmingly upper class perspective, the NYT cannot be considered a right-wing paper); but because they were insiders who refused to follow the rules of the culture, and who therefore threatened that culture.

Over the past two decades, journalists have fashioned a remarkably self-serving code of conduct: de- emphasizing factual accuracy; embracing a lazy herd mentality with talk of narratives and memes; avoiding tough confrontations through false equivalencies; and passing the buck on keeping their audience informed.

When Nate Silver pointed out both that the data didn't support many of the popular narratives and that the journalists pushing those narratives were contributing nothing, he threatened reputations, business models and the underlying culture of the institutions. The fact that he was right was beside the point; he was ignoring the conventions of the journalistic establishment and there is no greater bastion of that establishment than the New York Times. By the same token, when Krugman points out that "centrist" pundits have a huge personal and professional interest in pushing the "Paul Ryan, serious policy guy" narrative, he was expressing a fact that was widely known but which was not supposed to be said aloud.

The paper has never been exactly friendly to blunt, independent writers with satirical tendencies as Molly Ivins discovered way back in the Seventies, but things have only gotten worse since then. Almost everybody lives in glass houses now and Paul Krugman does not look like someone you'd trust with a rock in that situation.

TPM has a short but fascinating revelation

MSNBC host Joe Scarborough said Thursday that a public editor at the New York Times considers liberal columnist Paul Krugman's work to be an ongoing "nightmare."Assuming that Scarborough is on the level (and putting aside Ferguson's self-awareness issues), this would seem to echo the New York Times' reaction to Nate Silver. In both cases, the supposedly liberal staff seemed to take an instant dislike to highly respected liberal writer/researchers who appear to have brought in a large number of traditional and digital subscribers. What's going on?

During a segment on "Morning Joe," conservative historian Niall Ferguson joined Scarborough to pile on Krugman. Ferguson said that Krugman lacks "humility, honesty and civility."

"And there's no accountability," Ferguson said. "No one seems to edit that blog at the New York Times. And it's time that somebody called him out. People are afraid of him. I'm not."

Scarborough then recalled a conversation he had with a Times editor following his televised debate with Krugman earlier this year.

"I actually won't tell you which public editor it was but one of the public editors of the New York Times told me off the record after my debate that their biggest nightmare was his column every week," Scarborough said.

As regulars have probably guessed, I see this as another result of an increasingly dysfunctional culture of journalism, specifically the way that journalists react to having someone on the inside who ignores the implicit code of conduct.

This is not a left/right matter -- it cuts across pretty much all of the media establishment -- but conservatives have tended to make better tactical use of the rules we're talking about, for instance, using pox-on-both-their-houses conventions to provide cover for unpopular positions. As a result, there are more obvious targets on the right but that's a fairly trivial factor.

Silver and Krugman prompted such a strong reaction not because they were too liberal (despite seeing the world through an overwhelmingly upper class perspective, the NYT cannot be considered a right-wing paper); but because they were insiders who refused to follow the rules of the culture, and who therefore threatened that culture.

Over the past two decades, journalists have fashioned a remarkably self-serving code of conduct: de- emphasizing factual accuracy; embracing a lazy herd mentality with talk of narratives and memes; avoiding tough confrontations through false equivalencies; and passing the buck on keeping their audience informed.

When Nate Silver pointed out both that the data didn't support many of the popular narratives and that the journalists pushing those narratives were contributing nothing, he threatened reputations, business models and the underlying culture of the institutions. The fact that he was right was beside the point; he was ignoring the conventions of the journalistic establishment and there is no greater bastion of that establishment than the New York Times. By the same token, when Krugman points out that "centrist" pundits have a huge personal and professional interest in pushing the "Paul Ryan, serious policy guy" narrative, he was expressing a fact that was widely known but which was not supposed to be said aloud.

The paper has never been exactly friendly to blunt, independent writers with satirical tendencies as Molly Ivins discovered way back in the Seventies, but things have only gotten worse since then. Almost everybody lives in glass houses now and Paul Krugman does not look like someone you'd trust with a rock in that situation.

Monday, October 17, 2016

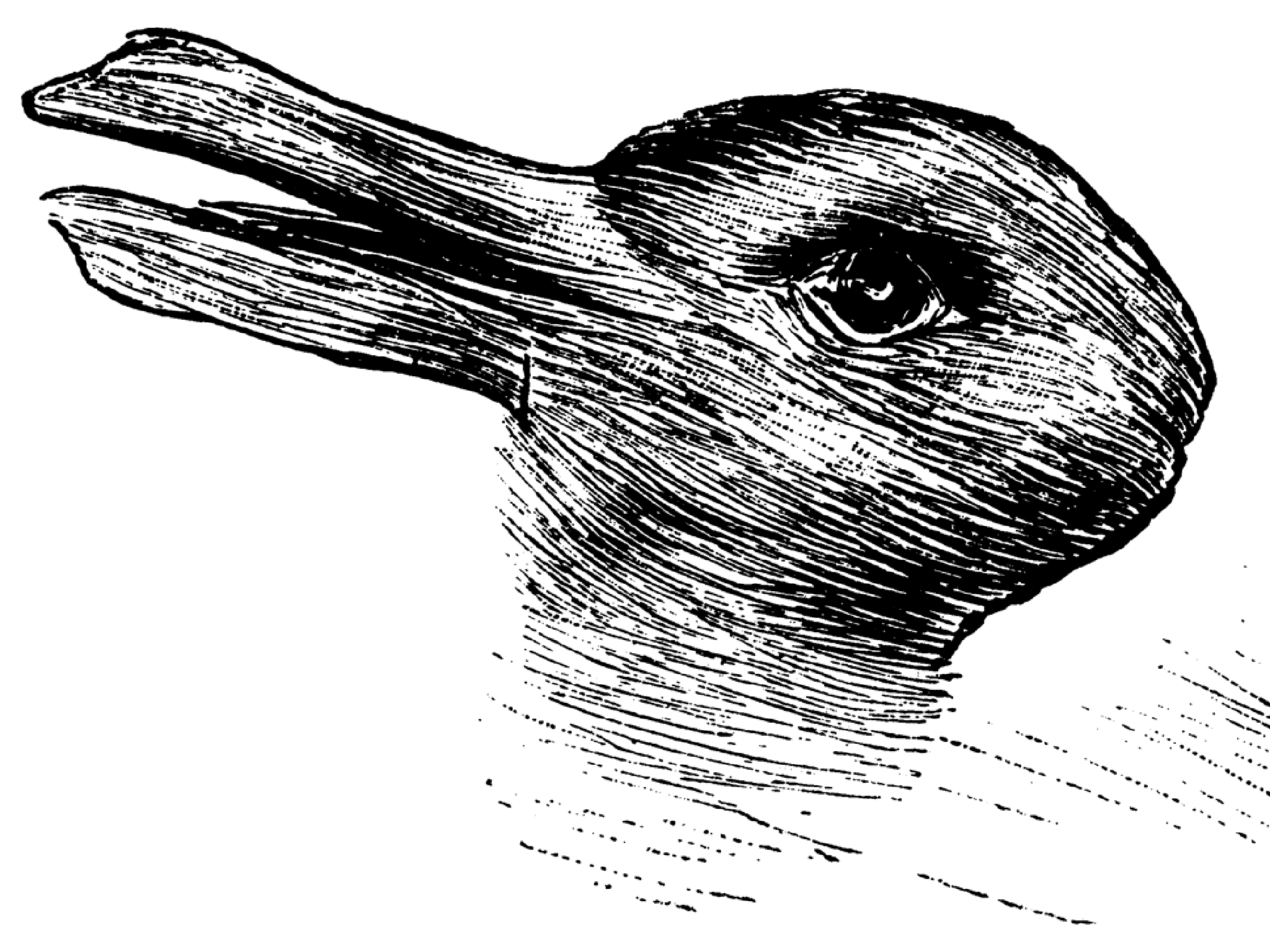

Rabbit season! Duck season! Rabbit season!

I'm planning on coming back and elaborating more on this later, but, as frequently noted here and elsewhere, while most commentators have fared extraordinarily poorly over the past year, a handful (including, yes, your not-so-humble hosts) have had a good run. Though they may not have framed it in exactly these terms, pretty much everybody who has gotten it mostly right has approached the election as the final stages of a massive social engineering experiment conducted by the conservative movement.

A key component of this experiment involved setting up radically different information streams for different target audiences. We talked about this before but one aspect that I've always wanted to address but never managed to get to is the way that this dual stream can explain seeming paradoxes in the radically different reactions of different groups of people to the same information.

In order to get a handle on this, it might be useful to think back to that time in psych 101 when the professor brought out the ambiguous pictures.The standard example is the old woman and young woman (originally captioned in a cartoon as "my wife and my mother-in-law"). For the sake of variety, let's go with another.

The psych lecture would go something like this. Half the class was told to cover their eyes, the other half was shown a series of slides of birds. Then that half of the class was told to cover their eyes and the other half was shown a series of slides of small mammals. After being thus prepared, everyone looks at the following picture and is asked to write down what they see.

For the commentators who took the time to dig through the various media streams and put themselves in the place of each target audience (most notably Josh Marshall), it has been obvious for quite a while that those in the right-wing media bubble have a strong tendency to interpret events in a way that is consistent with the information, framing and narratives of the bubble. Donald Trump succeeded in the primaries because both his arguments and his affect seemed reasonable in the context of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh.

I'll come back and fill in some more details later but, as much as I want to avoid oversimplifying, this really is pretty simple. The journalists who have come off as sharp and ahead of the curve, have all (as far as I can tell) looked seriously at right-wing media and have asked themselves, if I actually believed everything I just heard, how would I react to the different candidates and their proposals?

This begs loads of questions and I don't want to oversell the explanatory power here, but given all of the overheated rhetoric about how chaotic and unpredictable this election has been, it's worth noting when those getting it right have something in common.

A key component of this experiment involved setting up radically different information streams for different target audiences. We talked about this before but one aspect that I've always wanted to address but never managed to get to is the way that this dual stream can explain seeming paradoxes in the radically different reactions of different groups of people to the same information.

In order to get a handle on this, it might be useful to think back to that time in psych 101 when the professor brought out the ambiguous pictures.The standard example is the old woman and young woman (originally captioned in a cartoon as "my wife and my mother-in-law"). For the sake of variety, let's go with another.

The psych lecture would go something like this. Half the class was told to cover their eyes, the other half was shown a series of slides of birds. Then that half of the class was told to cover their eyes and the other half was shown a series of slides of small mammals. After being thus prepared, everyone looks at the following picture and is asked to write down what they see.

For the commentators who took the time to dig through the various media streams and put themselves in the place of each target audience (most notably Josh Marshall), it has been obvious for quite a while that those in the right-wing media bubble have a strong tendency to interpret events in a way that is consistent with the information, framing and narratives of the bubble. Donald Trump succeeded in the primaries because both his arguments and his affect seemed reasonable in the context of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh.

I'll come back and fill in some more details later but, as much as I want to avoid oversimplifying, this really is pretty simple. The journalists who have come off as sharp and ahead of the curve, have all (as far as I can tell) looked seriously at right-wing media and have asked themselves, if I actually believed everything I just heard, how would I react to the different candidates and their proposals?

This begs loads of questions and I don't want to oversell the explanatory power here, but given all of the overheated rhetoric about how chaotic and unpredictable this election has been, it's worth noting when those getting it right have something in common.

Sunday, October 16, 2016

What they're reading today in Utah

Pat Bagley cartoon from the Salt Lake Tribune, Sunday, Oct. 16, 2016

A few quick notes:

1. The Salt Lake Tribune is not a particularly right-wing paper (it endorsed Obama over Romney) but it does have the city's largest weekday circulation and it obviously speaks for a substantial part of the population;

2. The city's other major paper, the Deseret News also came out strongly against Trump;

3. Just to be clear, the point of this and other recent posts on the subject is not that the Republican Party is about to lose the support of groups like Mormons and evangelicals. I'm just saying that there are signs that these longstanding relationships are growing unstable, which does push some interesting scenarios into the realm of the plausible.

Friday, October 14, 2016

If you're following politics, you need to be following the religious right. If you're following the religious right, you should be following Charles Pierce.

When it comes to the intersection between politics and the Catholic Church, there's no better source than the old Irishman. This bit of territory has become particularly interesting because the religious right and most of the conventional poli-sci wisdom around it evolved under John Paul II and Benedict XVI. The Vatican is now a very different place, and those differences have already started

destabilizing what a lot of people had assumed were immutable political relationships.

Here's Pierce on the reaction the comments about the Church in the leaked Clinton emails.

Just take that old post I wrote and substitute "Mormon" for "Evangelical"

When two denominations of the same religion recognize sharply different sacred texts, there will always be tremendous tension, particularly when one or both have fundamentalist tendencies. In a sense, the similarities feed the tension as much as the differences do.

With Mormons and evangelicals, the similarities are remarkable. In terms of piety and personal morality, there is a great deal of common ground and in both cases, sincere believers who tend to be conservative face a real crisis of conscience when it comes to supporting the current Republican nominees.

With Mormons and evangelicals, the similarities are remarkable. In terms of piety and personal morality, there is a great deal of common ground and in both cases, sincere believers who tend to be conservative face a real crisis of conscience when it comes to supporting the current Republican nominees.

SALT LAKE CITY — Republican Donald Trump appears to have, in his earlier words, "a tremendous problem in Utah" as a new poll shows him slipping into a dead heat with Democrat Hillary Clinton since crude comments he made about women surfaced last weekend.

And along with the billionaire businessman's sudden fall, independent candidate and BYU graduate Evan McMullin surged into a statistical tie with the two major party presidential nominees, according to survey conducted Monday and Tuesday by Salt Lake City-based Y2 Analytics.

"A third-party candidate could win Utah as Utahns settle on one," said Quin Monson, Y2 Analytics founding partner.

McMullin may well have caught lightning in a bottle.

The poll shows Clinton and Trump tied at 26 percent, McMullin with 22 percent and Libertarian Gary Johnson getting 14 percent if the election were held today. Y2 Analytics surveyed 500 likely Utah voters over landlines and cellphones Oct. 10-11 The poll has a plus or minus 4.4 percent margin of error.

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Thinking about the rigged election narrative in catastrophe theory terms

Couple of quick notes before we start. First, I haven't looked at a book on catastrophe theory for many, many years. Therefore, the chances of my saying something stupid are even higher than normal. Second, I have a feeling that we've had this conversation before, but I am kind of rushed and, to be perfectly honest, it's quicker for me to dictate this into my phone then to dig through the archives of the blog. Apologies for any disconcerting sense of déjà vu that might result.

First, a relevant paragraph from Josh Marshall:

We are deep in bifurcation territory. Every snowflake that falls will have the likely effect of either slightly increasing the depth of the pile for sharply diminishing it.

One of the fundamental assumptions of the conservative movement has been that the angrier you get your base, the more you can count on their votes and their money. If you accept that, there is an undeniable logic behind the decision to portray lost elections as "stolen."

Unfortunately, it is also logical to assume that the argument "it is absolutely essential that you vote even though you know your vote won't matter" will eventually reach some breaking point. This can be particularly dangerous because it has the potential to strike across the spectrum of support. That's because the damage here can come both from those who question the official party narrative (who think you're a whiner) and from those who believe it (who have no reason t go to the polls)..

First, a relevant paragraph from Josh Marshall:

It now seems quite likely that Hillary Clinton will win the November election and become the next President of the United States. But Donald Trump has been for months pushing the idea that the election may be stolen from him by some mix of voter fraud (by racial and ethnic minorities) or more systemic election rigging by persons unknown. Polls show that large numbers of his supporters believe this.

We are deep in bifurcation territory. Every snowflake that falls will have the likely effect of either slightly increasing the depth of the pile for sharply diminishing it.

One of the fundamental assumptions of the conservative movement has been that the angrier you get your base, the more you can count on their votes and their money. If you accept that, there is an undeniable logic behind the decision to portray lost elections as "stolen."

Unfortunately, it is also logical to assume that the argument "it is absolutely essential that you vote even though you know your vote won't matter" will eventually reach some breaking point. This can be particularly dangerous because it has the potential to strike across the spectrum of support. That's because the damage here can come both from those who question the official party narrative (who think you're a whiner) and from those who believe it (who have no reason t go to the polls)..

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

And you thought #LeaveItBlank was out there

Insert Peter Thiel joke here.

From the New Republic:

From the New Republic:

On Wednesday #repealthe19th started trending among male Trump supporters, after an article by FiveThirtyEight observed that if women didn’t vote, Trump would have a far better chance of winning the presidential election.

Evangelicals and the clarifying shock

Remember our long-running thread on the curious relationship between the evangelicals and the conservative movement?

[From 2015]

There have always been tensions inherent in this relationship and they have grown over the years. Fortunately for the leaders of the evangelical movement, the GOP has generally tried to minimize those tensions by picking acceptable candidates who, in turn, went out of their way to show respect to members of the religious right.

As he does in so many contexts, Donald Trump has thrown the long-standing conflicts and contradictions into stark relief.

Sarah Jones writing for the New Republic:

Ed Kilgore writing for New York Magazine:

[From 2015]

I grew up in the Bible Belt and spent all of my formative years arguing with fundamentalists so I feel comfortable with the following claim: in the past 40 years, the conservative movement has had a larger impact on the evangelical community than the evangelical community has had on the conservative movement. Obviously in these situations, influence always runs both ways, but the changes on one side have been greater and far more strategically useful. The very fact that we have an alliance between conservative Catholics, Protestants, and Mormons says volumes.

There have always been tensions inherent in this relationship and they have grown over the years. Fortunately for the leaders of the evangelical movement, the GOP has generally tried to minimize those tensions by picking acceptable candidates who, in turn, went out of their way to show respect to members of the religious right.

As he does in so many contexts, Donald Trump has thrown the long-standing conflicts and contradictions into stark relief.

Sarah Jones writing for the New Republic:

Among his hardcore fans, Trump will survive these scandals; his supporters are now making that clear to his detractors. But his pious boosters can’t count on the same. Trump’s principal appeal to voters is his devotion to capitalism, not God. The religious right, meanwhile, pins itself to a claim of moral superiority. It always had more to lose.

Some evangelicals, like the Southern Baptist Convention’s Russell Moore, understand this, and have publicly criticized Trump’s convenient conversion. But their voices were never enough to sway the rank-and-file. The religious right was never as unique as it wanted everyone to believe, and now Trump has revealed the movement’s superiority to be the ruse it’s always been.

The religious right isn’t dead yet. But after this election becomes history, the movement will be forced to reckon with the consequences of its quest for power. Young adults, who overwhelmingly oppose Trump, are already leaving conservative churches, and the religious right’s Trump moment will surely only fuel this trend. If it had maintained a consistent public morality, maybe it could have retained some countercultural appeal. Now that its most visible leaders have sacrificed that authority, it has nothing left.

The statements of Perkins et al may well be considered their movement’s suicide note. Who will now believe they care for the sanctity of so-called “traditional marriage?” They anointed an infamous philanderer their standard-bearer. And who will believe they oppose abortion because they care for women? They backed a man who thinks sexual assault makes a good joke. Generations will remember their support for one of the most publicly misogynist and racist presidential candidates in American history.

In the Gospel of Matthew, Christ tells his disciples that no one can serve two masters; you’ll be loyal to one and not to the other. By endorsing Trump, the religious right chose a master—and sacrificed everything it says it stands for.

Ed Kilgore writing for New York Magazine:

Describing the Christian right as a by-product of cultural panic rather than religious fidelity is not something that would have ever occurred to the older generation of conservative Evangelical leaders. And so it does not occur to them — in public, anyway — to doubt the calculations that brought them to the awkward position of supporting Donald Trump, a man who, aside from his crudeness and prejudice and history of sexual immorality, clearly and openly worships the golden calf of worldly success.

The intergenerational tensions among conservative Evangelicals likely won’t matter at all on November 8. But down the road, the experience of sacrificing their integrity for a failed presidential campaign may have an impact on Christian conservative leaders who haven’t already traded their birthright of independence for a mess of Republican Party pottage. As it happens, America’s largest conservative Evangelical faith community, the Southern Baptist Convention, is home both to Russell Moore and to Jerry Falwell Jr., heir to the “moral majority” mantle of his late father and Trump’s earliest and most stolid clerical supporter. The two men represent very different paths ahead for the people in the pews they represent.

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

I've got this idea for a movie about a celebrity fascist propelled to power through the support of baby boomers

I saw Wild in the Street the other night on the terrestrial superstation the Works. The 1968 film was pretty awful, but it is an interesting time capsule with a decent sound track (the hit was Shape Of Things To Come {at 7:25}, but the statisticians and demographers in the audience might want to check out Fifty Two Per Cent {at 4:42})

Pauline Kael talked about the film in her 1969 essay Trash, Art and the Movies. For the record, I'm in full agreement on The Scalphunters, was far less entertained by Wild in the Streets (I suspect it was more effective at the time), thought she was overly hard on Wild Angels and way off on 2001, but even when Kael's wrong, she's wrong in an interesting and insightful way. (if you need a review, pick up a used copy of Maltin's Movie Guide.)

Pauline Kael talked about the film in her 1969 essay Trash, Art and the Movies. For the record, I'm in full agreement on The Scalphunters, was far less entertained by Wild in the Streets (I suspect it was more effective at the time), thought she was overly hard on Wild Angels and way off on 2001, but even when Kael's wrong, she's wrong in an interesting and insightful way. (if you need a review, pick up a used copy of Maltin's Movie Guide.)

There is so much talk now about the art of the film that we may be in danger of forgetting that most of the movies we enjoy are not works of art. “The Scalphunters,” for example, was one of the few entertaining American movies this past year, but skillful though it was, one could hardly call it a work of art—if such terms are to have any useful meaning. Or, to take a really gross example, a movie that is as crudely made as “Wild in the Streets”—slammed together with spit and hysteria and opportunism—can nevertheless be enjoyable, though it is almost a classic example of an inartistic movie. What makes these movies—that are not works of art—enjoyable? “The Scalphunters” was more entertaining than most Westerns largely because Burt Lancaster and Ossie Davis were peculiarly funny together; part of the pleasure of the movie was trying to figure out what made them so funny. Burt Lancaster is an odd kind of comedian: what’s distinctive about him is that his comedy seems to come out of his physicality. In serious roles an undistinguished and too obviously hard-working actor, he has an apparently effortless flair for comedy and nothing is more infectious than an actor who can relax in front of the camera as if he were having a good time. (George Segal sometimes seems to have this gift of a wonderful amiability, and Brigitte Bardot was radiant with it in “Viva Maria!”) Somehow the alchemy of personality in the pairing of Lancaster and Ossie Davis—another powerfully funny actor of tremendous physical presence—worked, and the director Sydney Pollack kept tight control so that it wasn’t overdone.

And “Wild in the Streets?” It’s a blatantly crummy-looking picture, but that somehow works for it instead of against it because it’s smart in a lot of ways that better-made pictures aren’t. It looks like other recent products from American International Pictures but it’s as if one were reading a comic strip that looked just like the strip of the day before, and yet on this new one there are surprising expressions on the faces and some of the balloons are really witty. There’s not a trace of sensitivity in the drawing or in the ideas, and there’s something rather specially funny about wit without any grace at all; it can be enjoyed in a particularly crude way—as Pop wit. The basic idea is corny—It Can’t Happen Here with the freaked-out young as a new breed of fascists—but it’s treated in the paranoid style of editorials about youth (it even begins by blaming everything on the parents). And a cheap idea that is this current and widespread has an almost lunatic charm, a nightmare gaiety. There’s a relish that people have for the idea of drug-taking kids as monsters threatening them—the daily papers merging into “Village of the Damned.” Tapping and exploiting this kind of hysteria for a satirical fantasy, the writer Robert Thom has used what is available and obvious but he’s done it with just enough mockery and style to make it funny. He throws in touches of characterization and occasional lines that are not there just to further the plot, and these throwaways make odd connections so that the movie becomes almost frolicsome in its paranoia (and in its delight in its own cleverness).

If you went to “Wild in the Streets” expecting a good movie, you’d probably be appalled because the directing is unskilled and the music is banal and many of the ideas in the script are scarcely even carried out, and almost every detail is messed up (the casting director has used bit players and extras who are decades too old for their roles). It’s a paste-up job of cheap movie-making, but it has genuinely funny performers who seize their opportunities and throw their good lines like boomerangs—Diane Varsi (like an even more zonked-out Geraldine Page) doing a perfectly quietly convincing freak-out as if it were truly a put-on of the whole straight world; Hal Holbrook with his inexpressive actorish face that is opaque and uninteresting in long shot but in close-up reveals tiny little shifts of expression, slight tightenings of the features that are like the movement of thought; and Shelley Winters, of course, and Christopher Jones. It’s not so terrible—it may even be a relief—for a movie to be without the look of art; there are much worse things aesthetically than the crude good-natured crumminess, the undisguised reach for a fast buck, of movies without art. From “I Was a Teen-Age Werewolf” through the beach parties to “Wild in the Streets” and “The Savage Seven,” American International Pictures has sold a cheap commodity, which in its lack of artistry and in its blatant and sometimes funny way of delivering action serves to remind us that one of the great appeals of movies is that we don’t have to take them too seriously.

“Wild in the Streets” is a fluke—a borderline, special case of a movie that is entertaining because some talented people got a chance to do something at American International that the more respectable companies were too nervous to try. But though I don’t enjoy a movie so obvious and badly done as the big American International hit, “The Wild Angels,” it’s easy to see why kids do and why many people in other countries do. Their reasons are basically why we all started going to the movies. After a time, we may want more, but audiences who have been forced to wade through the thick middle-class padding of more expensively made movies to get to the action enjoy the nose-thumbing at “good taste” of cheap movies that stick to the raw materials. At some basic level they like the pictures to be cheaply done, they enjoy the crudeness; it’s a breather, a vacation from proper behavior and good taste and required responses. Patrons of burlesque applaud politely for the graceful erotic dancer but go wild for the lewd lummox who bangs her big hips around. That’s what they go to burlesque for. Personally, I hope for a reasonable minimum of finesse, and movies like “Planet of the Apes” or “The Scalphunters” or “The Thomas Crown Affair” seem to me minimal entertainment for a relaxed evening’s pleasure. These are, to use traditional common-sense language, “good movies” or “good bad movies”—slick, reasonably inventive, well crafted. They are not art. But they are almost the maximum of what we’re now getting from American movies, and not only these but much worse movies are talked about as “art”—and are beginning to be taken seriously in our schools.

It’s preposterously egocentric to call anything we enjoy art—as if we could not be entertained by it if it were not; it’s just as preposterous to let prestigious, expensive advertising snow us into thinking we’re getting art for our money when we haven’t even had a good time. I did have a good time at “Wild in the Streets,” which is more than I can say for “Petulia” or “2001” or a lot of other highly praised pictures. “Wild in the Streets” is not a work of art, but then I don’t think “Petulia” or “2001” is either, though “Petulia” has that kaleidoscopic hip look and “2001” that new-techniques look which combined with “swinging” or “serious” ideas often pass for motion picture art.

Monday, October 10, 2016

On Sunday posts, electoral math, voter psychology, marketability, and the care and feeding of black swans.

[This is try number two. The first was lost when my iPhone decided that a 40% charge on the battery was dangerously low and decided to shut down just as I was about to hit send on the email of my dictation. This is yet another issue I wish Apple had prioritized over coming up with new headphone jacks.]

I recently posted a couple of items on undervoting and its implications. These were done in haste and there were a few points I did not have a chance to get to.

Sunday posting

Regular readers know that we generally take the weekends off here at West Coast Stat Views. Recently, though, events have been moving so rapidly that a delay of 48 or even 24 hours can mean the difference between looking prescient and being behind the curve.

Electoral math

I may not have been clear about this the previous posts. In terms of electoral outcomes, there is virtually no difference between the undervoting I described and voting for a fringe candidate ('fringe' implying that here she has no chance of winning).

Voter psychology

Here is where we start seeing a difference. The meaning of fringe party votes is inevitably muddy. Are you voting for them because you genuinely think they are the best candidates or simply because they do not have Democratic or Republican after their names? Leaving the race blank on the ballot sends a clean message.

Marketability

In terms of going viral on a national level, one of the problems with fringe-vote as protest is that the voters' options vary from state to state and race to race. #LeaveItBlank is simply more manageable than...

#IfThereIsAnAcceptableCandidateWhoIsNotADemocratOrRepublicanVoteForHimOrHerOtherwiseWriteInTheNameOfSomeoneYouLike.

Care and feeding

I apologize, but the discussion is going to get a bit meta now. I may get some pushback on this, but I believe that most data journalists and quite a few political scientists covering this race have made one of the most fundamental errors in analytic thinking. They have all acknowledged that these are abnormal times but they have locked themselves into normal mode. Think about all of the articles we've seen over the past year that start by admitting that long-held assumptions have been violated and that well-established models are proving unstable, then go on to use those same assumptions and models to make confident predictions.

I'm not making predictions here. I am simply throwing out what I think are plausible but generally not likely scenarios. I have no intention of applying even a rough subjective probability at this point. I've been watching this game for a while and I've seen way too many people fail to find the queen.

What I am saying is that we need to think about these problems using tools and approaches that are appropriate for abnormal times.

I recently posted a couple of items on undervoting and its implications. These were done in haste and there were a few points I did not have a chance to get to.

Sunday posting

Regular readers know that we generally take the weekends off here at West Coast Stat Views. Recently, though, events have been moving so rapidly that a delay of 48 or even 24 hours can mean the difference between looking prescient and being behind the curve.

Electoral math

I may not have been clear about this the previous posts. In terms of electoral outcomes, there is virtually no difference between the undervoting I described and voting for a fringe candidate ('fringe' implying that here she has no chance of winning).

Voter psychology

Here is where we start seeing a difference. The meaning of fringe party votes is inevitably muddy. Are you voting for them because you genuinely think they are the best candidates or simply because they do not have Democratic or Republican after their names? Leaving the race blank on the ballot sends a clean message.

Marketability

In terms of going viral on a national level, one of the problems with fringe-vote as protest is that the voters' options vary from state to state and race to race. #LeaveItBlank is simply more manageable than...

#IfThereIsAnAcceptableCandidateWhoIsNotADemocratOrRepublicanVoteForHimOrHerOtherwiseWriteInTheNameOfSomeoneYouLike.

Care and feeding

I apologize, but the discussion is going to get a bit meta now. I may get some pushback on this, but I believe that most data journalists and quite a few political scientists covering this race have made one of the most fundamental errors in analytic thinking. They have all acknowledged that these are abnormal times but they have locked themselves into normal mode. Think about all of the articles we've seen over the past year that start by admitting that long-held assumptions have been violated and that well-established models are proving unstable, then go on to use those same assumptions and models to make confident predictions.

I'm not making predictions here. I am simply throwing out what I think are plausible but generally not likely scenarios. I have no intention of applying even a rough subjective probability at this point. I've been watching this game for a while and I've seen way too many people fail to find the queen.

What I am saying is that we need to think about these problems using tools and approaches that are appropriate for abnormal times.

Sunday, October 9, 2016

#Leaveitblank?

Following up on the idea of undervoting. Take a look at these stories from Yahoo

and Josh Marshall

With this in mind, think about this scenario. Just to be clear, I'm not making a prediction here, just throwing out some hypotheticals to play with.

Imagine the following – – For lack of a better word let's call it a meme – – takes hold among hard-core Trump supporters angry at these Republican defections.

#LeaveItBlank

The idea being that you should still show up to the polls and vote, but when you get to a race where the Republican candidate has offended you, you leave that section blank. I'm not saying this is likely, but it's not exactly unimaginable at the moment either. If emotions continue to run high or even intensify, one could easily picture this sort of thing happening either from the bottom up or from the top down.

Let's think about the second possibility. Is anyone out there prepared to say with absolute confidence that Donald Trump is incapable of standing up at a rally in, say, Arizona and telling his supporters "if you don't like either of the candidates for the [pause] I don't know, senate race, you can just leave it blank."

I don't think this is particularly likely, but stranger things have certainly happened over the past 12 months.

There's a much bigger topic here (way to big for a Sunday afternoon post) about range of data and model stability and the way that chaotic conditions and unsustainable situations can make what was unthinkable merely unlikely.

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump took to Twitter on Sunday morning to push back against the GOP officials calling for him to drop out of the race in the aftermath of his lewd-video scandal.

“So many self-righteous hypocrites. Watch their poll numbers — and elections — go down!” he exclaimed.

Trump posted that tweet shortly after sharing messages from supporters railing against Republican “traitors” for bailing on their own party’s nominee.

and Josh Marshall

Yesterday I noted that there were two conversations going on in the GOP. One is party elites and officeholders finally distancing themselves or fully cutting ties with Donald Trump. The other is GOP voters themselves. They only started to make themselves heard yesterday afternoon when they booed and heckled Paul Ryan, Nevada Senate candidate Joe Heck and others in afternoon rallies. We can now see them in a fuller light in the first post-Trump Tape poll.

The poll is from Politico and Morning Consult. I've stated elsewhere that I'm somewhat skeptical of the methodology used by MC and some similar digital pollsters. But in this case we're not talking about matters of a few percentage points in a horse race poll but rather a very broad brush look at immediate public reactions to the tape. The upshot is that while GOP elites may finally be done with Trump they appear not to speak, even remotely, for base Republican voters. According to the Politico/MC poll, only 12% of Republicans want Trump to drop out of the race. And 74% say party leaders should continue to stand behind him.

There are various permutations of these numbers in the poll - how negatively people felt watching the video, how they feel about Trump personally, etc. But they all echo the point from those first two numbers. Republican voters aren't done with Trump, not remotely. And they overwhelmingly want party leaders to stand behind him.

The political drama of the last two days reminds me of those days in the Spring when #NeverTrump Republicans were spinning out theories about how they were going to use this or that trick to deny Trump the nomination. All great plans except for the fact that they hadn't taken into account that the people who they count on for votes did want Trump. In the end none of it came to anything after Republican elites (and I use the term here in the purely descriptive sense of the word) made contact with their voters.

Yesterday evening, after I watched more of the heckling and saw Trump fixing on the same as a show of support for him, it occurred to me that the presidential race's impact on Congress could be dramatically greater than we've imagined. This isn't a matter of people being so deeply outraged about the tape. It's more structural than that. The party leadership, at least as of last night, is in the midst of abandoning Trump. They're not quite there yet. But they're close. They probably saw overnight polls crating on Friday. I've seen various reports of private campaign polls registering this as a first response to the tape. It's worth remembering that even 10% of Republicans moving away from Trump would show up in a big way on those reports. But seeing those polls, retreating to their own instinctive suspicion and in many cases hostility toward Trump, they didn't give a lot of immediate thought to where the bulk of their voters stand. This poll makes pretty clear - as the booing and heckling did anecdotally - that they're with Trump.

With this in mind, think about this scenario. Just to be clear, I'm not making a prediction here, just throwing out some hypotheticals to play with.

Imagine the following – – For lack of a better word let's call it a meme – – takes hold among hard-core Trump supporters angry at these Republican defections.

#LeaveItBlank

The idea being that you should still show up to the polls and vote, but when you get to a race where the Republican candidate has offended you, you leave that section blank. I'm not saying this is likely, but it's not exactly unimaginable at the moment either. If emotions continue to run high or even intensify, one could easily picture this sort of thing happening either from the bottom up or from the top down.

Let's think about the second possibility. Is anyone out there prepared to say with absolute confidence that Donald Trump is incapable of standing up at a rally in, say, Arizona and telling his supporters "if you don't like either of the candidates for the [pause] I don't know, senate race, you can just leave it blank."

I don't think this is particularly likely, but stranger things have certainly happened over the past 12 months.

There's a much bigger topic here (way to big for a Sunday afternoon post) about range of data and model stability and the way that chaotic conditions and unsustainable situations can make what was unthinkable merely unlikely.

Saturday, October 8, 2016

If you start hearing this word a lot a month from now, remember you heard it here first

I'm not saying this is likely; I'm just saying that it might be a concept to have on your radar, particularly in places like New Hampshire.

Undervote (from Wikipedia)

Undervote (from Wikipedia)

An undervote occurs when the number of choices selected by a voter in a contest is less than the minimum number allowed for that contest or when no selection is made for a single choice contest.

In a contested election, an undervote can be construed as active voter disaffection - a voter engaged enough to cast a vote without the willingness to give the vote to any candidate.

Friday, October 7, 2016

"The Conspiracy Behind Your Glasses"

I have a couple of reasons for posting this.

First, I never need much of an excuse to plug a College Humor video, particularly from the "Adam Ruins Everything" spinoff series.

Second, this ties in with our ongoing thread about monopolies. You would think I'd be used to it by now, but it still catches me offguard when I'm reminded how bad things have gotten and how blatant and openly abused monopolistic power can be before anyone steps in and mentions the dreaded A word.

First, I never need much of an excuse to plug a College Humor video, particularly from the "Adam Ruins Everything" spinoff series.

Second, this ties in with our ongoing thread about monopolies. You would think I'd be used to it by now, but it still catches me offguard when I'm reminded how bad things have gotten and how blatant and openly abused monopolistic power can be before anyone steps in and mentions the dreaded A word.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

It was good enough for Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor

I'm probably the only person who had this reaction to this weekend's Trump taxes story.

There seem to be two parts to the story as originally presented (it's evolving rapidly). The first, which was generally the primary focus of reports and interviews on the subject, was that we now have evidence that supports a scenario by which Donald Trump might have legally avoided paying taxes for almost two decades.

Even with a conventional candidate, I'm not certain how big a story this would be. Of course, not paying taxes always looks bad, but does this seem that much worse to the general audience than any of the other byzantine maneuvers be very rich use to minimize their tax burden? (Assuming that all of this is legal, but more on that in a minute)

How do you make a small fortune? Give Donald Trump a large one.

Then there's the part about losing a billion dollars. In some sense, I think it might have been better for Trump had he been caught evading taxes in a less legal but more clever way. If it came down to a choice, he would much rather be seen as sharp and successful than as honest and ethical. It is no coincidence that when the subject came up during the debate, Trump pointed at not paying taxes as evidence that he was "smart." Not paying taxes, even for a number of years, because you lost a huge amount of money does not send the proper message.

Now we're learning that Trump's accountants were a bit more clever and considerably more sleazy than initially reported, but I suspect that those later developments are playing more to the news junkie crowd, and even that crowd seems to be ignoring the question that interests me.

Why the New York Times?

As we have frequently mentioned before, the best news analyst of the campaign has clearly been Josh Marshall. Talking Points Memo is a small organization, but pound for pound they do unequaled work. If you wanted to leak details of Trump's finances to the people who could best make sense of it, that would be an excellent choice.

If, however, you wanted to limit yourself to a large organization, the obvious choice would be the Washington Post. In terms of both quality and quantity, the paper's reporting on Trump (particularly that of David Fahrenthold) has left all of its peers in the dust.

If you were basing your decision on individual journalists rather than organizations, Marshall and Fahrenthold would certainly be good choices, but given the combination of Trump and taxes, I might go with David Cay Johnston.

If, however, you wanted to make an impact, wanted to dominate the conversation the next day, you would probably do what the source did in this case and send your information to the New York Times.

The New York Times continues to hold the most valuable real estate in journalism. If you have a cause you want to promote or a narrative you want to shape, there is simply no one else who can compete. This has all sorts of implications for the paper and for journalism in general.

To be fair, the paper has a large number of fantastic reporters and when it focuses its efforts on solid, old-fashioned investigative journalism, the results can be remarkable, but the paper's position also means that it can scoop the competition with little or no effort. In a very real sense, the news comes to it.

This access to sources can easily become a dependence on them. We previously talked about the decade of terrible journalism marked by Whitewater, the 2000 election, and the build up to the Iraq war. We also talked about the lead role that the New York Times played in all three of those stories.

One important common thread in all three stories was that none of them were driven in a significant way by real original investigative reporting. In all the cases, the narratives were largely shaped by sources with ulterior motives who found cooperative reporters such as Judith Miller who were willing to pass on what they were told.

So, what are the lessons we should draw from this?

1. In journalism as in so many other things, it is good to be the king. As we just said, the news often comes to you. On top of that, when multiple organizations are reporting the same story, yours is the one that tends to be quoted the most, even when your coverage is based on reporting of others. These and other factors make it relatively easy for the perceived industry leader to maintain its position. They also present a strong temptation to rest on your laurels.

2. Being the king also brings with it huge responsibilities. Bad journalism from the New York Times can do more damage than bad journalism from any other publication.

3. The New York Times unique access to leaks and highly placed sources is both a resource and a risk. In the case of the Trump tax returns. In the case of the Trump tax returns, it was the former but recently it has often been more the latter.

Consider this passage from then public editor Margaret Sullivan (I wonder if anyone at the paper realizes how much they lost when she left).

This is the irony of the New York Times. Its greatest advantage often leads to its worst moments.

There seem to be two parts to the story as originally presented (it's evolving rapidly). The first, which was generally the primary focus of reports and interviews on the subject, was that we now have evidence that supports a scenario by which Donald Trump might have legally avoided paying taxes for almost two decades.

Even with a conventional candidate, I'm not certain how big a story this would be. Of course, not paying taxes always looks bad, but does this seem that much worse to the general audience than any of the other byzantine maneuvers be very rich use to minimize their tax burden? (Assuming that all of this is legal, but more on that in a minute)

How do you make a small fortune? Give Donald Trump a large one.

Then there's the part about losing a billion dollars. In some sense, I think it might have been better for Trump had he been caught evading taxes in a less legal but more clever way. If it came down to a choice, he would much rather be seen as sharp and successful than as honest and ethical. It is no coincidence that when the subject came up during the debate, Trump pointed at not paying taxes as evidence that he was "smart." Not paying taxes, even for a number of years, because you lost a huge amount of money does not send the proper message.

Now we're learning that Trump's accountants were a bit more clever and considerably more sleazy than initially reported, but I suspect that those later developments are playing more to the news junkie crowd, and even that crowd seems to be ignoring the question that interests me.

Why the New York Times?

As we have frequently mentioned before, the best news analyst of the campaign has clearly been Josh Marshall. Talking Points Memo is a small organization, but pound for pound they do unequaled work. If you wanted to leak details of Trump's finances to the people who could best make sense of it, that would be an excellent choice.

If, however, you wanted to limit yourself to a large organization, the obvious choice would be the Washington Post. In terms of both quality and quantity, the paper's reporting on Trump (particularly that of David Fahrenthold) has left all of its peers in the dust.

If you were basing your decision on individual journalists rather than organizations, Marshall and Fahrenthold would certainly be good choices, but given the combination of Trump and taxes, I might go with David Cay Johnston.

If, however, you wanted to make an impact, wanted to dominate the conversation the next day, you would probably do what the source did in this case and send your information to the New York Times.

The New York Times continues to hold the most valuable real estate in journalism. If you have a cause you want to promote or a narrative you want to shape, there is simply no one else who can compete. This has all sorts of implications for the paper and for journalism in general.

To be fair, the paper has a large number of fantastic reporters and when it focuses its efforts on solid, old-fashioned investigative journalism, the results can be remarkable, but the paper's position also means that it can scoop the competition with little or no effort. In a very real sense, the news comes to it.

This access to sources can easily become a dependence on them. We previously talked about the decade of terrible journalism marked by Whitewater, the 2000 election, and the build up to the Iraq war. We also talked about the lead role that the New York Times played in all three of those stories.

One important common thread in all three stories was that none of them were driven in a significant way by real original investigative reporting. In all the cases, the narratives were largely shaped by sources with ulterior motives who found cooperative reporters such as Judith Miller who were willing to pass on what they were told.

So, what are the lessons we should draw from this?

1. In journalism as in so many other things, it is good to be the king. As we just said, the news often comes to you. On top of that, when multiple organizations are reporting the same story, yours is the one that tends to be quoted the most, even when your coverage is based on reporting of others. These and other factors make it relatively easy for the perceived industry leader to maintain its position. They also present a strong temptation to rest on your laurels.

2. Being the king also brings with it huge responsibilities. Bad journalism from the New York Times can do more damage than bad journalism from any other publication.

3. The New York Times unique access to leaks and highly placed sources is both a resource and a risk. In the case of the Trump tax returns. In the case of the Trump tax returns, it was the former but recently it has often been more the latter.

Consider this passage from then public editor Margaret Sullivan (I wonder if anyone at the paper realizes how much they lost when she left).

Mistakes are bound to happen in the news business, but some are worse than others.

What I’ll lay out here was a bad one. It involved a failure of sufficient skepticism at every level of the reporting and editing process — especially since the story in question relied on anonymous government sources, as too many Times articles do.

…

The Times needs to fix its overuse of unnamed government sources. And it needs to slow down the reporting and editing process, especially in the fever-pitch atmosphere surrounding a major news event. Those are procedural changes, and they are needed. But most of all, and more fundamental, the paper needs to show far more skepticism – a kind of prosecutorial scrutiny — at every level of the process.

Two front-page, anonymously sourced stories in a few months have required editors’ notes that corrected key elements – elements that were integral enough to form the basis of the headlines in both cases. That’s not acceptable for Times readers or for the paper’s credibility, which is its most precious asset.

If this isn’t a red alert, I don’t know what will be.

This is the irony of the New York Times. Its greatest advantage often leads to its worst moments.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)