A music historian I know speaks eloquently about this very long piece (the first ten minutes of which can be heard here). He has listened to most if not all of the piece (I did mention it was long, right?) and he says the key is letting yourself give in to the pace of the music, though I suspect that his complete familiarity with the composition being adapted helps a bit.

If you're interested in classical or experimental music, take a listen at the link above then click here to see what you've just heard.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Saturday, July 13, 2013

Friday, July 12, 2013

Apologist Watch

There is a danger in using small incidents to make big arguments. List enough anecdotes and you can often overwhelm by sheer weight even though, with time, someone could probably amass a comparable pile on the other side of the debate. But that doesn't mean we should ignore all information that doesn't come in big, clean, conclusive data sets. Even an old-school frequentist will acknowledge the value of a reality check, seeing how well and how often the world matches your theories.

Take, for instance, the argument that the quality of today's journalism has been damaged by the group dynamics of the profession and particularly by the tendency of media critics to adopt the role of group apologists. With that hypothesis in mind, look at these two paragraphs from Politico's Dylan Byers (expertly satirized by Esquire's Charles Pierce).

Those would be interesting topics for another discussion, but what's relevant here is the social dynamic. Outsiders play a joke on some insiders and trick them into doing something stupid. Byers concedes that the insiders shouldn't have been stupid but complains that the joke wasn't funny. That's pretty much the expected response of a group apologist under the circumstances, made doubly problematic by the fact that a lot of people are laughing.

p.s. Sorry about being so late to get this one out.

Take, for instance, the argument that the quality of today's journalism has been damaged by the group dynamics of the profession and particularly by the tendency of media critics to adopt the role of group apologists. With that hypothesis in mind, look at these two paragraphs from Politico's Dylan Byers (expertly satirized by Esquire's Charles Pierce).

This is not the first time folks have been fooled by The Daily Currant. In February, The Washington Post picked up one of the site's stories and erroneously reported that Sarah Palin was joining Al Jazeera. In March, both the Boston Globe and Breitbart.com ran reports that Paul Krugman had filed for personal bankruptcy, again based on a Daily Currant report. Needless to say, the real journalists bear the responsibility here: They should verify the news they report or, at the very least, know the sources from which they aggregate.As Pierce notes, Byers would be fine if he stopped here. Unfortunately he follows with this:

But these mistakes don't reflect well on The Daily Currant, either. If their stories are plausible, it's because they aren't funny enough. No one -- almost no one -- mistakes The Onion for a real news organization. That's not just because it has greater brand recognition. It's because their stories make readers laugh. Here are some recent headlines from The Onion: "Dick Cheney Vice Presidential Library Opens In Pitch-Dark, Sulfurous Underground Cave" ... "John Kerry Lost Somewhere In Gobi Desert" ... "'F--- You,' Obama Says In Hilarious Correspondents' Dinner Speech." Here are some recent headlines from The Daily Currant: "Obama Instantly Backs Off Plan to Close Guantanamo" ... "CNN Head Suggests Covering More News for Ratings" ... "Santorum Pulls Son Out of Basketball League."There are at least a couple of critical fallacies here. The first is, as Pierce observes, confusing title and story. The other is the assumption that the humor and effectiveness of satire depends on its obviousness (has anyone at Politico read "a Modest Proposal"?).

Those would be interesting topics for another discussion, but what's relevant here is the social dynamic. Outsiders play a joke on some insiders and trick them into doing something stupid. Byers concedes that the insiders shouldn't have been stupid but complains that the joke wasn't funny. That's pretty much the expected response of a group apologist under the circumstances, made doubly problematic by the fact that a lot of people are laughing.

p.s. Sorry about being so late to get this one out.

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Data points

You could use this anecdote as a launching point for any number of interesting discussions, but I think it might be more valuable if it simply stands on its own as an example off how school policies are made and implemented.

16-year-old Kiera Wilmot is accused of mixing housing chemicals in a small water bottle at Bartow High School, causing the cap to fly off and produce a bit of smoke. The experiment was conducted outdoors, no property was damaged, and no one was injured.

Not long after Wilmot’s experiment, authorities arrested her and charged her with “possession/discharge of a weapon on school property and discharging a destructive device,” according to WTSP-TV. The school district proceeded to expel Wilmot for handling the “dangerous weapon,” also known as a water bottle. She will have to complete her high school education through an expulsion program.

Friends and staffers, including the school principal, came to Wilmot’s defense, telling media that authorities arrested an upstanding student who meant no harm.

"She is a good kid," principal Ron Richard told WTSP-TV. "She has never been in trouble before. Ever."

"She just wanted to see what happened to those chemicals in the bottle," a classmate added. "Now, look what happened."

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

I have no doubt these numbers were pulled from someplace other than "thin air"

I have no opinion on the price of a share of Disney, but as of now I'm a bit more inclined to short Credit Suisse:

1. Movies are an unpredictable business, particularly movies scheduled for release two years from now.

2. Senno is predicting a extraordinarily rare event. According to Wikipedia, only five films have broken $1.2 billion in global ticket sales

1 Avatar $2,782,275,172 2009

2 Titanic $2,185,372,302 1997

3 The Avengers $1,511,757,910 2012

4 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 $1,341,511,219 2011

5 Iron Man 3 (currently playing) $1,211,010,987 2013

3. Though the data jumps around quite a bit, when we correct for inflation, there's reason to believe that the box office of the Star Wars franchise is trending down. With inflation, the first film made far more than the Phantom Menace (check my numbers but I believe almost twice) which made more than considerably more than the latest.

Of course, it's entirely possible that this reboot will hit Avengers territory -- all of the films in the franchise have been enormously profitable -- but the idea that someone can forecast this with any level of confidence is simply silly.

None of this is meant to be taken as a comment on the value of Disney stock which could be badly undervalued as far as I know. What this is a reminder of is how often we are fed unbelievable numbers and, more troublingly, how often established institutions are willing to put their reputations behind them.

Here's something you don't see very often. The Walt Disney Company suffered a major bomb over the weekend, opening The Lone Ranger to a pitiful $48 million 5-day box office, forcing the studio to lose an anticipated $150 million on the big-budget Western. But if you're a Disney stockholder, things are still looking up. According to Variety the studio's stock is up 1.3%. Why? You probably already know the answer: Star Wars.

OK, partial credit goes to Monsters University and Iron Man 3, two huge hits that help soften the blow of The Lone Ranger's failure. But Credit Suisse analyst Michael Senno estimates that Disney will make $733 million in profit-- that's $1.2 billion in global ticket sales-- from Star Wars Episode VII, which means that the company still ought to remain a solid investment. He didn't pull that number out from thin air, of course-- the final Star Wars prequel, Revenge of the Sith, made $850 million worldwide, and of course Disney's last giant hit The Avengers was a huge global success, making $1.5 billion. If anything, $1.2 billion for Star Wars Episode VII might be lowballing it.First, a quick belaboring of the obvious...

1. Movies are an unpredictable business, particularly movies scheduled for release two years from now.

2. Senno is predicting a extraordinarily rare event. According to Wikipedia, only five films have broken $1.2 billion in global ticket sales

1 Avatar $2,782,275,172 2009

2 Titanic $2,185,372,302 1997

3 The Avengers $1,511,757,910 2012

4 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 $1,341,511,219 2011

5 Iron Man 3 (currently playing) $1,211,010,987 2013

3. Though the data jumps around quite a bit, when we correct for inflation, there's reason to believe that the box office of the Star Wars franchise is trending down. With inflation, the first film made far more than the Phantom Menace (check my numbers but I believe almost twice) which made more than considerably more than the latest.

Of course, it's entirely possible that this reboot will hit Avengers territory -- all of the films in the franchise have been enormously profitable -- but the idea that someone can forecast this with any level of confidence is simply silly.

None of this is meant to be taken as a comment on the value of Disney stock which could be badly undervalued as far as I know. What this is a reminder of is how often we are fed unbelievable numbers and, more troublingly, how often established institutions are willing to put their reputations behind them.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

[Insert joke headline here]

Just when I was starting to feel bad about that Marx Brothers crack this comes along (from Yahoo):

In an attempt to ban Internet cafes in the Sunshine State, legislators may have been a bit too broad in their language, resulting in what some legal experts say is a law that inadvertently makes it illegal to own a computer or a smartphone.

The bill, which was signed into law by Florida governor Rick Scott in April, was meant to shut down cafes, some of which have been tied to illegal gambling in the state. And shut them down it did: over 1,000 cafes were immediately closed.

But it's the wording that's problematic, as it defines a slot machine as "any machine or device or system or network of devices" that can be used in games of chance. Turns out the Internet is full of gambling sites, which is where the definition runs into some problems.

The show business equivalent of a patent troll -- more from the post pretense stage of intellectual property

Back on the IP beat, take a look at this item from Entertainment Weekly:

None of the standard defenses of copyright apply here. This is a work completely forgotten by the general public, unseen for almost a century, created by people long dead, of no conventional value as a piece of intellectual property. There's no way Warner Bros. (which didn't even produce the 1916 film) can argue this is anything more than rent seeking and the harassment of smaller competitors.

That's what I meant when I called this the post-pretense stage of intellectual property rights. Up until a few decades ago, I believe we were in the sincere stage: patent and copyright laws were, for the most part, honest attempts at protecting creators' rights and encouraging the creation of socially and economically beneficial art and technology. Then came the pretense stage, where the arguments about protecting creators and encouraging invention were used as cover for powerful interests to hang on to valuable government-granted monopolies (or in this case industry-granted -- not that surprising since the same major players that dominate industry organizations are the ones that benefit most from and lobby hardest for these laws). Now we're entering the stage where even the pretense of fairness and social good can no longer be maintained with a straight face.

The Weinstein Company’s upcoming movie The Butler, which stars Forest Whitaker as the African-American servant who worked in the White House for more than 40 years, has tripped over an industry obstacle on the way to its Aug. 16 release in theaters. As Deadline reported Monday, Warner Bros. is claiming protective rights to the film’s title due to a 1916 silent short film with the same name that resides in its archives, and both sides are heading to arbitration to reach a resolution.

Technically, this isn’t a legal issue, since you can’t typically copyright or trademark a movie title. But the MPAA has a voluntary Title Registration Bureau that the industry uses to self-regulate and avoid title conflicts that might confuse audiences. In this case, it’s unlikely that moviegoers are even aware of the 1916 silent film that Warner Bros. is citing, but TWC apparently never cleared the title.Just so we're clear, my obscurity bar is alarmingly high, but the Butler (1916) clears it in street shoes. This short subject seems to have been forgotten almost on its release. No one of any note was involved either in front of or behind the camera. It doesn't seem to have had any airings in any media after the late Teens. There's no plot synopsis on IMDB or, as far as I can tell, anywhere else on line and though we can only guess at what the film is about, one thing we can say with near certainty is that it has nothing whatsoever to do with the Forest Whitaker movie.

None of the standard defenses of copyright apply here. This is a work completely forgotten by the general public, unseen for almost a century, created by people long dead, of no conventional value as a piece of intellectual property. There's no way Warner Bros. (which didn't even produce the 1916 film) can argue this is anything more than rent seeking and the harassment of smaller competitors.

That's what I meant when I called this the post-pretense stage of intellectual property rights. Up until a few decades ago, I believe we were in the sincere stage: patent and copyright laws were, for the most part, honest attempts at protecting creators' rights and encouraging the creation of socially and economically beneficial art and technology. Then came the pretense stage, where the arguments about protecting creators and encouraging invention were used as cover for powerful interests to hang on to valuable government-granted monopolies (or in this case industry-granted -- not that surprising since the same major players that dominate industry organizations are the ones that benefit most from and lobby hardest for these laws). Now we're entering the stage where even the pretense of fairness and social good can no longer be maintained with a straight face.

Monday, July 8, 2013

S&P defense

In a startling approach, S&P seems to be making a claim that their ratings are marketing activities and not a credible estimate of credit-worthiness. I am going to outsource the obvious conclusion from Matthew Yglesias:

In case you have trouble imaging this defense, Kevin Drum posted a picture showing the actual text. What passes imagination is that the US government has written these ratings into law in terms of what pension funds can invest in. If this is just paid marketing, should we not repeal these laws? And would that not remove what little is left of the business model?

What am I missing here?

If talk of objectivity is just marketing hype, then the ratings are worthless. It's just a form of paid public relations for security issuers and nobody should take the ratings seriously for a minute.

In case you have trouble imaging this defense, Kevin Drum posted a picture showing the actual text. What passes imagination is that the US government has written these ratings into law in terms of what pension funds can invest in. If this is just paid marketing, should we not repeal these laws? And would that not remove what little is left of the business model?

What am I missing here?

"Don't you cry for me..."

In the recent IP thread (see here, here, here and here to get caught up), Joseph and I have generally been bemoaning regulatory capture and trying to make the case that ludicrously broad patents and endlessly extended copyrights are socially costly. We were not, however, arguing for the other extreme, a world of no intellectual property protection where "information wants to be free." We've seen how how things work in a world where copyrights go unenforced:

Just so there's no room for confusion, Joseph and I are arguing for the middle ground for IP protection, such as what we saw with American copyrights from 1909 to 1976 (a period that represented a pretty good run).

Stephen Collins Foster (July 4, 1826 – January 13, 1864), known as the "father of American music", was an American songwriter primarily known for his parlour and minstrel music. Foster wrote over 200 songs; among his best known are "Oh! Susanna", "Camptown Races", "Old Folks at Home", "My Old Kentucky Home", "Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair", "Old Black Joe", and "Beautiful Dreamer". Many of his compositions remain popular more than 150 years after he wrote them.

...

Stephen Foster had become impoverished while living at the North American Hotel at 30 Bowery on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York. He was reportedly confined to his bed for days by a persistent fever; Foster tried to call a chambermaid, but collapsed, falling against the washbasin next to his bed and shattering it, which gouged his head. It took three hours to get him to Bellevue Hospital. In an era before transfusions and antibiotics, he succumbed three days after his admittance, aged 37.

His worn leather wallet contained a scrap of paper that simply said, "Dear friends and gentle hearts," along with 38 cents in Civil War scrip and three pennies.(According to a music historian I know, the example of Foster was very much on the minds of the people who created ASCAP fifty years later.)

Just so there's no room for confusion, Joseph and I are arguing for the middle ground for IP protection, such as what we saw with American copyrights from 1909 to 1976 (a period that represented a pretty good run).

Intellectual Property and Merit

Mark and I had an offline discussion about how intellectual property law (intended to reward innovators) can often be co-opted by large financial interests who have much more bargaining power. The classic example is a band signing up for their first record deal -- there is a lot of pressure to sign with a label and the negotiations may be asymmetric unless the group has an amazing agent.

In the same sense, Chris Dillow has a great piece on how many innovators were too far ahead of their time and never reaped the rewards of their innovation. The classic example is Doug Engelbert:

He goes on to discuss a number of other examples in technology, music, and sports. That this happens is, I think, quite clear unless the definition of innovation becomes aliased with the definition of marketing; if you do alias innovation with marketing (e.g. making the mouse computer tool popular and/or getting large companies interested in it) then it becomes rather unclear what the compelling government interest is. Selling good ideas to large companies is its own reward and does not really need a government subsidy to continue to be a rewarding activity. Creating a new drug or technology, on the other hand, is important and the compelling interest in making these things happen is much clearer.

Now, this may be a straw man in the sense of market theory (as you can have rich and complex theories about how markets should reward merit and it is hard to easily generalize). But I think it bears reflection in the sense of intellectual property. In what sense are we motivating innovation with these laws and what is the right balance to strike. That is a much more interesting line of discussion.

In the same sense, Chris Dillow has a great piece on how many innovators were too far ahead of their time and never reaped the rewards of their innovation. The classic example is Doug Engelbert:

Doug Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse, did not make much money from his invention because its patent expired in 1987, before the surge in demand for home comupters. This fact poses a problem for people daft enough to think that markets reward merit - because it's quite common for very meritorious people to fail simply by being ahead of their time.

He goes on to discuss a number of other examples in technology, music, and sports. That this happens is, I think, quite clear unless the definition of innovation becomes aliased with the definition of marketing; if you do alias innovation with marketing (e.g. making the mouse computer tool popular and/or getting large companies interested in it) then it becomes rather unclear what the compelling government interest is. Selling good ideas to large companies is its own reward and does not really need a government subsidy to continue to be a rewarding activity. Creating a new drug or technology, on the other hand, is important and the compelling interest in making these things happen is much clearer.

Now, this may be a straw man in the sense of market theory (as you can have rich and complex theories about how markets should reward merit and it is hard to easily generalize). But I think it bears reflection in the sense of intellectual property. In what sense are we motivating innovation with these laws and what is the right balance to strike. That is a much more interesting line of discussion.

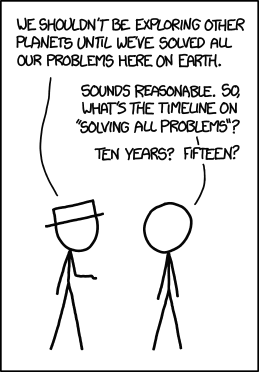

Straw Stick Men

You can find about sixty years worth of arguments suggesting that planetary exploration should be deferred until we have addressed some immediate problem (cure cancer, end pollution, etc.). I don't want to defend these arguments -- at least not in their blanket form -- but I do feel obliged to point out that I've never seen anyone that we should wait until we've solved "all our problems."

Saturday, July 6, 2013

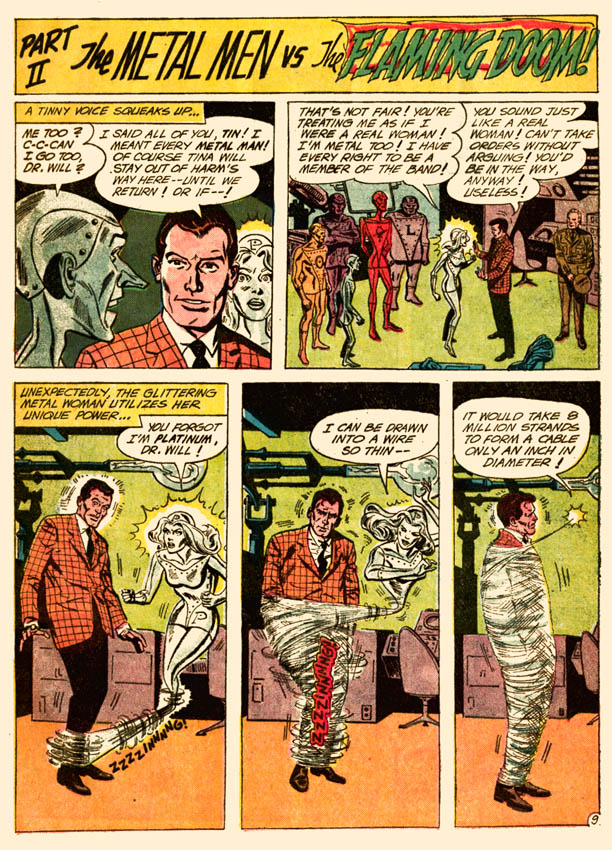

Weekend blogging -- the surprising overlap between chemistry majors and comic book nerds

OK... maybe not all that surprising.

Here's the description from Freetech4teachers:

(apparently we have made some progress in gender attitudes in the past fifty years.)

Here's the description from Freetech4teachers:

The Periodic Table of Comic Books is a project of the chemistry department at the University of Kentucky. The idea is that for every element in the Periodic Table of Elements there is a comic book reference. Clicking on an element in the periodic table displayed on the homepage will take visitors to a list and images of comic book references to that particular element. After looking at the comic book reference if visitors want more information about a particular element they can find it by using the provided link to Web Elements.Here are a couple of the items you'll find under Platinum.

(apparently we have made some progress in gender attitudes in the past fifty years.)

Friday, July 5, 2013

The real issue

Frances Woolley gets to the heart of the problem with citibike that Mark and I have been discussing:

So the biggest problem is that there just isn't a consensus on dealing with this problem. At the margins, a carbon tax would be purely good news. It would raise revenue and that would be a good thing in a low tax country (kind of like cigarette and alcohol taxes being very positive revenue generators). But even a "revenue neutral tax" can be opposed over fears that it might end up generating additional tax revenue. In what other context would this be rational? Would we be worried about accepting employment because there might be a pay raise? Is it not good for the central government to have as many different levers as possible to collect revenue?

In that context, citibike is an interesting flash point because it illustrates just how entrenched the opposition to meaningful change is (i.e. even when the change is trivial it brings forth strong emotions). Yet we need to develop meaningful alternatives to the status quo at some point, even if it is just when all of the oil is consumed.

The biggest losers from a carbon tax are people like my cousins in the exurbs. The map above, taken from a paper by VandeWeghe and Kennedy, highlights the parts of Toronto with the highest per capita carbon consumption in red. These are place where people live in reasonably large houses, and commute long distances to work, generating whopping carbon footprints. The whole purpose of a carbon tax is to discourage this type of lifestyle. But I can see why people are reluctant to give it up. Except for the commute, it's great. The streets are quiet, clean and friendly, and there's lots of green space near by. For a person who wants a garden and ample living space, the alternative housing options in the same price range are clearly less desirable: a small, unrenovated bungalow in Scarborough, say, or a downtown condo.This is really what is going to be the core issue of carbon reform. Right now we subsidize the exurbs and the large living space ideal. If you don't believe me, just think of what the response would be to a plan to stop keeping commuter roads in place in order to save money. Or to just banning cars in NYC, as they are clearly inefficient relative to alternatives. It'd be brutal. Yet nobody has an equivalent problem with massive cuts to public transit.

So the biggest problem is that there just isn't a consensus on dealing with this problem. At the margins, a carbon tax would be purely good news. It would raise revenue and that would be a good thing in a low tax country (kind of like cigarette and alcohol taxes being very positive revenue generators). But even a "revenue neutral tax" can be opposed over fears that it might end up generating additional tax revenue. In what other context would this be rational? Would we be worried about accepting employment because there might be a pay raise? Is it not good for the central government to have as many different levers as possible to collect revenue?

In that context, citibike is an interesting flash point because it illustrates just how entrenched the opposition to meaningful change is (i.e. even when the change is trivial it brings forth strong emotions). Yet we need to develop meaningful alternatives to the status quo at some point, even if it is just when all of the oil is consumed.

A very different perspective on the NYC bike share program

Check here to get up to speed on the discussion.

At least for me, big posts tend to bring a lot of little posts in their wake. In the course of fact checking and looking up background, interesting facts pop up that make for brief, freestanding posts. Since these are quick to write, they usually get posted before the piece that inspired them (thus somewhat mixing the wake metaphor). Sometimes the big posts never get finished, leaving the smaller ones with something of a non sequitur quality.

In the case of the recent bike share thread, the main topic I wanted to address was the way New York City's bike share program has been covered (particularly the environmental aspect) and how that coverage compares to other recent environmental stories.

Citi Bike has turned into a major national story. Here are some of the reasons I think it does not merit that level of attention:

More bicycles are not going to be a big part of the solution to our environmental and transportation problems. This is a cheap, reliable, and well-established technology that everybody knows about. As a result, most of the benefits of the technology have been realized. We can, of course, get still more by making cities more bike-friendly and bikes cheaper and more convenient, but there's not a lot of low hanging fruit here, particularly when compared to steps like fixing rail choke points and shifting over to more plug in hybrids and electric vehicles;

Bike share programs can only play a limited role in promoting cycling. Bikes are already cheap and easily stored and transported, thus limiting the incremental value. Furthermore, sharing programs work best in the same high density areas where public transportation is generally most plentiful;

The New York City example is likely to have little impact on the future of bike share programs. We're talking about an extraordinarily unrepresentative place, expensive, densely populated, compact with so little available space that even bike parking is an issue, and served by an exceptional public transportation system. It's going to be difficult to widely generalize from that experience.

This is not to say that the NYC program and ride sharing in general aren't admirable and worthwhile programs -- give me an initiative, I'll vote for it -- but they remain a small part of a small part of the solution.

By comparison, a major international reduction in the use of coal might well be the most important thing we can do to address global warming and ocean acidification. It is also a story with huge economic implications and a long list of winners and losers.

By any reasonable standard, the Obama administration's recent proposed policy changes surrounding coal are a couple of orders of journalistic magnitude bigger than a bike share program in a single city, but that certainly doesn't seem to be reflected in the levels of coverage we've seen.

As an admittedly crude way of attaching some numbers to this I did the following Google news searches and noted the number of hits I got for certain phrases (no quotes). The actual numbers jumped around but the first position seems to remain the same

new york city bike share

About 65,000 results

obama climate change speech

About 57,500 results

obama climate change coal

41,700 results

I take a couple of things away from this. the first is the way that the culture of journalism affects what we see and read. The second is our ability to have the kind of discussion needed to solve big problems.

I've been making the point for a while now that the press corps has a problem with homogeneity and insularity. If you look at truly influential journalists and opinion makers, you will see certain groups highly over-represented (such as New Yorkers). It's only natural that stories which affect those groups tend to get noticed. What's less excusable is the apparent lack of awareness on the subject. There's nothing wrong with being an upper-middle to upper class, ivy-league educated professional who lives and/or works in NYC or DC. The is something wrong with assuming that most people share those circumstances, particularly if part of your job is providing a balanced account of things. The NYC bike share program has a disproportionate effect on important members of the press corps so it's not surprising that it receives disproportionate coverage. A similar dynamic tends to amplify the coverage of high end electronics and dampen coverage of items predominantly used by the lower-middle and lower classes like over the air TV (though that demographic is changing).

But the far bigger issue is our apparent inability to maintain the sense of prospective necessary for the kind of prioritized discussions that lead to solutions of big problems. I'm not saying there's no room for smaller matters but there needs to be some sense of proportionality. Important issues like coal policy, ocean acidification, CAFE standards and the future of nuclear power are often pushed to the back pages. Others, like rail choke points, receive almost no attention at all.

Obviously public discourse is not a zero sum game. The time we spend talking about bike sharing doesn't have to come out of the time we would have spent talking about fuel efficiency, but there are limits to our bandwidth and until we start giving appropriate attention to environmental issues, we simply won't have time for the small stuff.

At least for me, big posts tend to bring a lot of little posts in their wake. In the course of fact checking and looking up background, interesting facts pop up that make for brief, freestanding posts. Since these are quick to write, they usually get posted before the piece that inspired them (thus somewhat mixing the wake metaphor). Sometimes the big posts never get finished, leaving the smaller ones with something of a non sequitur quality.

In the case of the recent bike share thread, the main topic I wanted to address was the way New York City's bike share program has been covered (particularly the environmental aspect) and how that coverage compares to other recent environmental stories.

Citi Bike has turned into a major national story. Here are some of the reasons I think it does not merit that level of attention:

More bicycles are not going to be a big part of the solution to our environmental and transportation problems. This is a cheap, reliable, and well-established technology that everybody knows about. As a result, most of the benefits of the technology have been realized. We can, of course, get still more by making cities more bike-friendly and bikes cheaper and more convenient, but there's not a lot of low hanging fruit here, particularly when compared to steps like fixing rail choke points and shifting over to more plug in hybrids and electric vehicles;

Bike share programs can only play a limited role in promoting cycling. Bikes are already cheap and easily stored and transported, thus limiting the incremental value. Furthermore, sharing programs work best in the same high density areas where public transportation is generally most plentiful;

The New York City example is likely to have little impact on the future of bike share programs. We're talking about an extraordinarily unrepresentative place, expensive, densely populated, compact with so little available space that even bike parking is an issue, and served by an exceptional public transportation system. It's going to be difficult to widely generalize from that experience.

This is not to say that the NYC program and ride sharing in general aren't admirable and worthwhile programs -- give me an initiative, I'll vote for it -- but they remain a small part of a small part of the solution.

By comparison, a major international reduction in the use of coal might well be the most important thing we can do to address global warming and ocean acidification. It is also a story with huge economic implications and a long list of winners and losers.

By any reasonable standard, the Obama administration's recent proposed policy changes surrounding coal are a couple of orders of journalistic magnitude bigger than a bike share program in a single city, but that certainly doesn't seem to be reflected in the levels of coverage we've seen.

As an admittedly crude way of attaching some numbers to this I did the following Google news searches and noted the number of hits I got for certain phrases (no quotes). The actual numbers jumped around but the first position seems to remain the same

new york city bike share

About 65,000 results

obama climate change speech

About 57,500 results

obama climate change coal

41,700 results

I take a couple of things away from this. the first is the way that the culture of journalism affects what we see and read. The second is our ability to have the kind of discussion needed to solve big problems.

I've been making the point for a while now that the press corps has a problem with homogeneity and insularity. If you look at truly influential journalists and opinion makers, you will see certain groups highly over-represented (such as New Yorkers). It's only natural that stories which affect those groups tend to get noticed. What's less excusable is the apparent lack of awareness on the subject. There's nothing wrong with being an upper-middle to upper class, ivy-league educated professional who lives and/or works in NYC or DC. The is something wrong with assuming that most people share those circumstances, particularly if part of your job is providing a balanced account of things. The NYC bike share program has a disproportionate effect on important members of the press corps so it's not surprising that it receives disproportionate coverage. A similar dynamic tends to amplify the coverage of high end electronics and dampen coverage of items predominantly used by the lower-middle and lower classes like over the air TV (though that demographic is changing).

But the far bigger issue is our apparent inability to maintain the sense of prospective necessary for the kind of prioritized discussions that lead to solutions of big problems. I'm not saying there's no room for smaller matters but there needs to be some sense of proportionality. Important issues like coal policy, ocean acidification, CAFE standards and the future of nuclear power are often pushed to the back pages. Others, like rail choke points, receive almost no attention at all.

Obviously public discourse is not a zero sum game. The time we spend talking about bike sharing doesn't have to come out of the time we would have spent talking about fuel efficiency, but there are limits to our bandwidth and until we start giving appropriate attention to environmental issues, we simply won't have time for the small stuff.

Thursday, July 4, 2013

A perspective on bike culture

One point that I wanted to add to the discussion with Mark about bicycles is the importance of having a plan. In a lot of ways, I prefer a bad plan to no plan at all. Mostly because hard decisions made in the face of crisis tend to be sub-optimal. One question that really needs to be addressed in any discussion of trying to avoid climate change or creating a greener world is what will replace the current sources of greenhouse gas and/or pollution.

It may be the case that some things can be discontinued. But we need electricity for computers and we will always need to be able to travel from place to place. Walking has significant limitations.

What the bicycle crowd has is an option that might well work to replace short and medium length commutes. It has a lot of downsides and disadvantages. In a lot of ways I almost prefer golf carts, although given that golf carts mix well with bicycles this isn't a major problem.

This might be the wrong way forward -- I don't know. But I think that proposing a plan is a good forward step. Sure, it might be the case that the plan isn't going to survive scrutiny. But I would like to see alternative proposed that are not "we can keep the status quo forever" unless these plans address issues like peak oil and pollution thoughtfully.

So I like the conversation starting as that is so much better than pretending that there isn't going to be a problem.

It may be the case that some things can be discontinued. But we need electricity for computers and we will always need to be able to travel from place to place. Walking has significant limitations.

What the bicycle crowd has is an option that might well work to replace short and medium length commutes. It has a lot of downsides and disadvantages. In a lot of ways I almost prefer golf carts, although given that golf carts mix well with bicycles this isn't a major problem.

This might be the wrong way forward -- I don't know. But I think that proposing a plan is a good forward step. Sure, it might be the case that the plan isn't going to survive scrutiny. But I would like to see alternative proposed that are not "we can keep the status quo forever" unless these plans address issues like peak oil and pollution thoughtfully.

So I like the conversation starting as that is so much better than pretending that there isn't going to be a problem.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)