The result is that the normal state of affairs — where powerful individuals get trumped by even more powerful construction-industry inevitabilities — is turned on its head, to the point at which new construction can no longer keep up with the de-densification endemic to gentrification. Bloggers may rail against this state of affairs — both Ryan Avent and Matt Yglesias have written at great length about how important it is to allow new buildings to rise within urban areas — but ultimately the natural conservatism of the rich is winning out, across the nation. If you want to move to a city where density is going up rather than down, you might just have to move to Miami. Or China.I mean I like the idea of nice places to live and low density can be really pleasant in a lot of ways. But I think these thigns should be compromises and it is a sad fact of reality that growth and statis are going to be inevitability opposed.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Monday, May 6, 2013

Rich versus poor

It was interesting to go from reading this piece on the lives of the urban poor to this piece from Felix Salmon. I had not previously heard the term BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything), but it does seem to nicely reflect the sensibilities of the people in question. But the real issue is why this is a stable state of affairs:

flippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflippedflipped...

You know how, if you keep repeating the same word long enough it will eventually start to become meaningless? Over at Unqualified Offerings, Thoreau has a post up that shows that the education buzzword 'flipping' has apparently reached that stage.

This is one of the most annoying part of the education debate (and it's a discussion rich in annoyances): there some solid and enormously promising ideas behind many proposals for flipped and online classes, but they are completely lost amongst the garbage coming pundits who don't know the history and haven't thought through the issues, partisans looking to advance non-educational agendas and con artists trying to turn a quick buck (or some combination of the three).

Today a literature professor told me that her Dean had asked to consider “flipping” her class. Now, in a literature class the professor has to operate on the assumption that you’ve read the novel outside of class. Class time is devoted to discussion of the novel. Is that not the definition of “flipping”? Basic information is delivered outside of class, and class time is devoted to discussion, application, analysis, etc. Especially in a small class like hers. And, here’s the amazing thing: Back in 1994, before the internet was popular, before Khan Academy existed, I actually took a literature class like that. Can you believe it? A class that was “flipped” before the concept of “flipping” was a buzzword!We should stop and note that while it is possible to have a flipped online class, the viability of a flipped MOOC is far more questionable. The activities reserved for a flipped classroom aren't readily scalable, particularly if you're using a simplistic Thomas-Friedman definition of a MOOC.

Now, some of you might be saying that online literature classes exist, but that’s different from flipping. Flipping means moving the lower-level information delivery to outside of class, and then spending class time on discussion and higher level analysis. Yes, my friend will sometimes introduce a bit of information in class, e.g. discuss an analytical framework, or fill in some background information not present in the readings, but by and large the time is spent on discussion, not the basic outline of “Who is Hamlet? What country is he Prince of? What has happened in his life to make him so melancholy?” We’re talking about allocation of time and effort in the class, not moving the class online. Also, moving a literature class online does not automatically mean it’s “flipped.” In a non-flipped online class they’d spoon-feed you information on the novel, via powerpoints, video lectures, chats, whatever. In the flipped online class, they’d assume you’ve read the novel and devote video chats, discussions, or whatever other presentations to analysis of the novel.

This is one of the most annoying part of the education debate (and it's a discussion rich in annoyances): there some solid and enormously promising ideas behind many proposals for flipped and online classes, but they are completely lost amongst the garbage coming pundits who don't know the history and haven't thought through the issues, partisans looking to advance non-educational agendas and con artists trying to turn a quick buck (or some combination of the three).

"Segregated lives"

I've been thinking a lot about social and economic distance and what seems to be the increasing difficulty with which information travels to certain parts of the network and the tendency for members of certain subnetworks to mistake local perception for the global.

I suspect that Congress's swift action on the FAA (compared with complete inaction concerning the rest of the sequester) was based in part on mistaking attitudes toward flight delays within their subgroup for the attitudes of the nation as a whole.

Likewise the coverage of over-the-air television has been rife with errors and omissions (see here and here and almost every other story on the subject) in part because it's a product used primarily by the lower and lower-middle class.

Another aspect of this increased distance is greater difficulty forming professional networks that reach across demographics and economic and educational strata.

From How Social Networks Drive Black Unemployment by Nancy Ditomaso

I suspect that Congress's swift action on the FAA (compared with complete inaction concerning the rest of the sequester) was based in part on mistaking attitudes toward flight delays within their subgroup for the attitudes of the nation as a whole.

| The Daily Show with Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Cut Punters - The Sequestration Myth | ||||

| www.thedailyshow.com | ||||

| ||||

Likewise the coverage of over-the-air television has been rife with errors and omissions (see here and here and almost every other story on the subject) in part because it's a product used primarily by the lower and lower-middle class.

Another aspect of this increased distance is greater difficulty forming professional networks that reach across demographics and economic and educational strata.

From How Social Networks Drive Black Unemployment by Nancy Ditomaso

You don’t usually need a strong social network to land a low-wage job at a fast-food restaurant or retail store. But trying to land a coveted position that offers a good salary and benefits is a different story. To gain an edge, job seekers actively work connections with friends and family members in pursuit of these opportunities.Lots more on this coming soon.

Help is not given to just anyone, nor is it available from everyone. Inequality reproduces itself because help is typically reserved for people who are “like me”: the people who live in my neighborhood, those who attend my church or school or those with whom I have worked in the past. It is only natural that when there are jobs to be had, people who know about them will tell the people who are close to them, those with whom they identify, and those who at some point can reciprocate the favor.

Because we still live largely segregated lives, such networking fosters categorical inequality: whites help other whites, especially when unemployment is high. Although people from every background may try to help their own, whites are more likely to hold the sorts of jobs that are protected from market competition, that pay a living wage and that have the potential to teach skills and allow for job training and advancement. So, just as opportunities are unequally distributed, they are also unequally redistributed.

All of this may make sense intuitively, but most people are unaware of the way racial ties affect their job prospects.

Sunday, May 5, 2013

How many people today would refer to 2001 as our "historical yesterdays"?

Back on the decelerating future beat, here's Owen Wister's introduction to the Virginian in 1902.

TO THE READER

Certain of the newspapers, when this book was first announced, made a mistake most natural upon seeing the sub-title as it then stood, A TALE OF SUNDRY ADVENTURES. "This sounds like a historical novel," said one of them, meaning (I take it) a colonial romance. As it now stands, the title will scarce lead to such interpretation; yet none the less is this book historical—quite as much so as any colonial romance. Indeed, when you look at the root of the matter, it is a colonial romance. For Wyoming between 1874 and 1890 was a colony as wild as was Virginia one hundred years earlier. As wild, with a scantier population, and the same primitive joys and dangers. There were, to be sure, not so many Chippendale settees.

We know quite well the common understanding of the term "historical novel." HUGH WYNNE exactly fits it. But SILAS LAPHAM is a novel as perfectly historical as is Hugh Wynne, for it pictures an era and personifies a type. It matters not that in the one we find George Washington and in the other none save imaginary figures; else THE SCARLET LETTER were not historical. Nor does it matter that Dr. Mitchell did not live in the time of which he wrote, while Mr. Howells saw many Silas Laphams with his own eyes; else UNCLE TOM'S CABIN were not historical. Any narrative which presents faithfully a day and a generation is of necessity historical; and this one presents Wyoming between 1874 and 1890. Had you left New York or San Francisco at ten o'clock this morning, by noon the day after to-morrow you could step out at Cheyenne. There you would stand at the heart of the world that is the subject of my picture, yet you would look around you in vain for the reality. It is a vanished world. No journeys, save those which memory can take, will bring you to it now. The mountains are there, far and shining, and the sunlight, and the infinite earth, and the air that seems forever the true fountain of youth, but where is the buffalo, and the wild antelope, and where the horseman with his pasturing thousands? So like its old self does the sage-brush seem when revisited, that you wait for the horseman to appear.

But he will never come again. He rides in his historic yesterday. You will no more see him gallop out of the unchanging silence than you will see Columbus on the unchanging sea come sailing from Palos with his caravels.

And yet the horseman is still so near our day that in some chapters of this book, which were published separate at the close of the nineteenth century, the present tense was used. It is true no longer. In those chapters it has been changed, and verbs like "is" and "have" now read "was" and "had." Time has flowed faster than my ink.

Saturday, May 4, 2013

Weekend Blogging -- Puzzles! Puzzles! Puzzles!

As soon as I get caught up with a few other projects, I'm planning a regular classic puzzle feature over at my math teaching blog, You Do the Math. That got a lot easier when I found out (via Wikipedia of course) that two of Henry Ernest Dudeney's best known collections (Amusements in Mathematics and The Canterbury Puzzles) are available as free e-books from Project Gutenberg.

If you're the the type of person who can hear the phrase "recreational mathematics" without snickering and you don't already own a copy, you'll want to check these out. Here are a couple of tastes.

First, from Amusements:

Here's the answer.

And here's one from Canterbury:

You can find the answer to that one here.

Now on to Sam Loyd.

If you're the the type of person who can hear the phrase "recreational mathematics" without snickering and you don't already own a copy, you'll want to check these out. Here are a couple of tastes.

First, from Amusements:

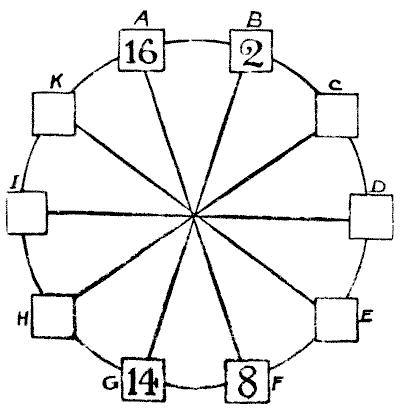

118.—CIRCLING THE SQUARES.

The puzzle is to place a different number in each of the ten squares so that the sum of the squares of any two adjacent numbers shall be equal to the sum of the squares of the two numbers diametrically opposite to them. The four numbers placed, as examples, must stand as they are. The square of 16 is 256, and the square of 2 is 4. Add these together, and the result is 260. Also—the square of 14 is 196, and the square of 8 is 64. These together also make 260. Now, in precisely the same way, B and C should be equal to G and H (the sum will not necessarily be 260), A and K to F and E, H and I to C and D, and so on, with any two adjoining squares in the circle.

All you have to do is to fill in the remaining six numbers. Fractions are not allowed, and I shall show that no number need contain more than two figures.

Here's the answer.

And here's one from Canterbury:

21.—The Ploughman's Puzzle.

The Ploughman—of whom Chaucer remarked, "A worker true and very good was he, Living in perfect peace and charity"—protested that riddles were not for simple minds like his, but he[Pg 44] would show the good pilgrims, if they willed it, one that he had frequently heard certain clever folk in his own neighbourhood discuss. "The lord of the manor in the part of Sussex whence I come hath a plantation of sixteen fair oak trees, and they be so set out that they make twelve rows with four trees in every row. Once on a time a man of deep learning, who happened to be travelling in those parts, did say that the sixteen trees might have been so planted that they would make so many as fifteen straight rows, with four trees in every row thereof. Can ye show me how this might be? Many have doubted that 'twere possible to be done." The illustration shows one of many ways of forming the twelve rows. How can we make fifteen?

You can find the answer to that one here.

Now on to Sam Loyd.

Friday, May 3, 2013

Sleazy but not atypical

More on bad narratives and the lengths some journalists will go to cling to them.

To talk about bad journalistic narratives implies that there are good ones out there. What would a good journalistic narrative look like? This is a complicated question -- narrative is a complex and elusive concept -- but there is one important aspect that we (being a statistically inclined crowd) should be able to get a handle on. A journalistic narrative is a hypothesis.

What do we ask of a hypothesis?

1. It should fit the facts;

2. The likelihood given our hypothesis of what happened should be greater than the likelihood given the previous hypothesis (the one most readers would reach given the facts);

3. There is not an obvious simpler hypothesis that meets conditions 1. and 2. as well as the new hypothesis does (personally, I like certain 700-year-old quotes but that is, perhaps, a topic for another post);

and if possible

4. It should have predictive value, provide insights and/or suggest interesting questions.

I got to thinking about this due to a post by David Silbey (via Thoma, of course) that addresses a repugnant piece by Jason Zengerle entitled How Savvy Jenny Sanford Sabotaged Ex-Husband Mark’s Political Comeback. Zengerle's title is, from the standpoint of grabbing attention, a good headline but it is also a bad narrative given the rules above.

Here's the previous hypothesis: Jenny Sanford has been open about her low opinion of her husband and this campaign but is not getting involved in this campaign.

And here's Zengerle's hypothesis: "Indeed, while Jenny has never come out and publicly opposed Mark’s congressional candidacy — choosing to remain officially neutral — she’s waged a brutally effective passive-aggressive campaign against it."

Zengerle then lists various events that are as or more consistent with the previous hypothesis than they are with his. Perfectly natural choices like bringing charges when you catch an ex-spouse sneaking out of your house are spun as part of a devious plot.

Zengerle gives us no reason to believe Jenny Sanford is being in any way dishonest or inconsistent; he just assumes we'd rather believe something sleazy.

To talk about bad journalistic narratives implies that there are good ones out there. What would a good journalistic narrative look like? This is a complicated question -- narrative is a complex and elusive concept -- but there is one important aspect that we (being a statistically inclined crowd) should be able to get a handle on. A journalistic narrative is a hypothesis.

What do we ask of a hypothesis?

1. It should fit the facts;

2. The likelihood given our hypothesis of what happened should be greater than the likelihood given the previous hypothesis (the one most readers would reach given the facts);

3. There is not an obvious simpler hypothesis that meets conditions 1. and 2. as well as the new hypothesis does (personally, I like certain 700-year-old quotes but that is, perhaps, a topic for another post);

and if possible

4. It should have predictive value, provide insights and/or suggest interesting questions.

I got to thinking about this due to a post by David Silbey (via Thoma, of course) that addresses a repugnant piece by Jason Zengerle entitled How Savvy Jenny Sanford Sabotaged Ex-Husband Mark’s Political Comeback. Zengerle's title is, from the standpoint of grabbing attention, a good headline but it is also a bad narrative given the rules above.

Here's the previous hypothesis: Jenny Sanford has been open about her low opinion of her husband and this campaign but is not getting involved in this campaign.

And here's Zengerle's hypothesis: "Indeed, while Jenny has never come out and publicly opposed Mark’s congressional candidacy — choosing to remain officially neutral — she’s waged a brutally effective passive-aggressive campaign against it."

Zengerle then lists various events that are as or more consistent with the previous hypothesis than they are with his. Perfectly natural choices like bringing charges when you catch an ex-spouse sneaking out of your house are spun as part of a devious plot.

Zengerle gives us no reason to believe Jenny Sanford is being in any way dishonest or inconsistent; he just assumes we'd rather believe something sleazy.

One hell of a multiplier

A small data point on the very big story of states using tax incentives to attract businesses. I was researching a post on an article on film and television in Georgia that mentioned the incentive package that convinced Disney to move the Miley Cyrus film The Last Song away from North Carolina.

Here's the relevant passage from Wikipedia:

If someone has a better number I'd be glad to revise this post, but until then, let's say eight to ten million was spent in Georgia by Disney and its employees in the summer of 2009. That's not a trivial amount of money. It certainly provided a big bump for the south Georgia economy; it may even have been worth the cost in state revenue, but to get to that 17.5, you have to assume that money is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

Of course, if you have a truly in state-production the story's quite different. For example, most of the money from Tyler Perry's next Madea film really will end up in Georgia.

But it's worth remembering, Perry started making movies in Georgia years before those incentives started.

Along related lines, check out James Kwak's thoughts on Rhode Island's $75 million loan to Curt Shilling's gaming company and Matt Yglesias's explanation of why the Kings stayed in Sacramento.

Here's the relevant passage from Wikipedia:

The Last Song had originally been set in Wrightsville Beach and Wilmington in North Carolina. Though they wished to shoot on location, filmmakers also examined three other states and identified Georgia as the next best filming site. Georgia’s housing prices were higher, but the state’s filming incentive package refunded 30% of production costs such as gasoline, pencils, and salaries. ...When you hear accounts of how much money a movie or a factory or a stadium brought to an area, you should maintain a healthy skepticism. According to that same Wikipedia article, the budget for the film was $20 million. Presumably almost all of the above-the-line costs and much of the rest of the budget (particularly post-production) went out of state.

Though other movies have been filmed in Tybee Island, The Last Song is the first to actually be set in Tybee. With the city’s name plastered on everything from police cars to businesses, Georgia officials predict a lasting effect on the economy. In addition, The Last Song is estimated to have brought up to 500 summer jobs to Georgia, $8 million to local businesses, and $17.5 million to state businesses.

If someone has a better number I'd be glad to revise this post, but until then, let's say eight to ten million was spent in Georgia by Disney and its employees in the summer of 2009. That's not a trivial amount of money. It certainly provided a big bump for the south Georgia economy; it may even have been worth the cost in state revenue, but to get to that 17.5, you have to assume that money is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

Of course, if you have a truly in state-production the story's quite different. For example, most of the money from Tyler Perry's next Madea film really will end up in Georgia.

But it's worth remembering, Perry started making movies in Georgia years before those incentives started.

Along related lines, check out James Kwak's thoughts on Rhode Island's $75 million loan to Curt Shilling's gaming company and Matt Yglesias's explanation of why the Kings stayed in Sacramento.

Oregon and Medicaid

The new Oregon Medicaid study is coming out at a very bad time for me to comment. But I want to direct you to the Incidental Economist which is doing a banner job of clarifying why it was hard to get good evidence directly on health outcomes from the study. Further comments are here.

One thing to note on health outcomes (poached from the comments at TIE) is:

I think that this is too harsh, but it does point out that many of the changes were clinically significant but that the study (for a lot of reasons due to enrollment and short follow-up) is not really able to give precise estimates. Remember, only 25% of the people offered Medicaid took it, so the adherence rate is a lot lower than what we normally think of in an RCT and so the intention to treat estimate is a poor measure of the associations among those who enrolled.

Kevin Drum discusses this more here. Pay special attention to the PDF at the bottom of the post.

One thing to note on health outcomes (poached from the comments at TIE) is:

In the case of total cholesterol the rate was reduced by 17% (from 14.1% to 11.7%). If that kind of drop is not detectable by the study then I think it is a problem.Or this one:

HgbA1C drops from 5.1% to 4.2%.

I think that this is too harsh, but it does point out that many of the changes were clinically significant but that the study (for a lot of reasons due to enrollment and short follow-up) is not really able to give precise estimates. Remember, only 25% of the people offered Medicaid took it, so the adherence rate is a lot lower than what we normally think of in an RCT and so the intention to treat estimate is a poor measure of the associations among those who enrolled.

Kevin Drum discusses this more here. Pay special attention to the PDF at the bottom of the post.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

It's too late for me to think of a sufficiently sarcastic title

I've always had a problem with Ken Rudin. I assume that, at some point he must have done some good work to get where he is, but I'm a regular NPR listener and I used to be a regular listener of Talk of the Nation and what I've heard has been consistently weak. More to the point, his weaknesses are completely consistent with the conventional Washington political world view.

The DC press corps has shown an extraordinary level of group-think and a truly stunning lack of self-awareness. Members have to constantly tune out contradictory facts and disturbing questions. Which takes us to last night's broadcast:

The DC press corps has shown an extraordinary level of group-think and a truly stunning lack of self-awareness. Members have to constantly tune out contradictory facts and disturbing questions. Which takes us to last night's broadcast:

DONVAN: You have been noodling on the prospects of Hillary Clinton 2016.If there was ever a moment that called for an epiphany, this is it. The man is asked straight out "why are you talking about this?" He admits that he doesn't know, that there's no reason for us to listen to him. Does he then take the next logical step and admit that he should spend less time talking about meaningless numbers? No. There is not a flicker of awareness. He just blithely goes back to drawing conclusions from the numbers he has just called nonsensical.

(LAUGHTER)

RUDIN: Well, other people have, as well, and, of course, there's a new poll - and God forbid we could talk about politics without talking about 2016, because it's only, you know, a million years away from now. But WMUR and University of New Hampshire has a new poll out that shows that Hillary Clinton, if the New Hampshire poll - if the New Hampshire primary were held today and, of course, if it were, then we'd be talking about something else, but Hillary Clinton would have 61 percent, and Joe Biden will only have 7 percent among the Democrats.

And on the Republican side, Marco Rubio and Rand Paul would be tied at 15 percent each. I mean, of course, these are nonsensical numbers, but the point is, as of now, May 2013, Hillary Clinton remains - again, I know this is ridiculous to say - but a prohibitive favorite for...

DONVAN: Yeah. But when you say it's ridiculous to say, why are those - why discuss those numbers at all right now? What relevance actually do they have?

RUDIN: Well, none. I guess, you know...

DONVAN: Oh, too bad.

RUDIN: No. I mean, it really has none. Look, the day of the New Hampshire primary in 2008, a lot of people predicted Barack Obama - who had won the Iowa caucuses - who was going to win the New Hampshire, and Hillary Clinton won New Hampshire. So if on the day of the primary we can't - you know, the polling doesn't show it to be accurate. The fact that we're talking about it two-and-a-half years later is just mind-boggling to me - three-and-a-half years later, two-and-a-half years later. It's mind-boggling. But what it does say is that, at least as of now, the Republican race is wide, wide open. And, of course, you know, it's very rare for a vice president to be denied the nomination if he or she would want it. And, of course, Joe Biden has a tough battle if Hillary Clinton runs.

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Two education posts of note

From Dana Goldstein: An Activist Teacher, a Struggling School, and the School Closure Movement: A Story from L.A.

From Dean Dad: No Pell for Remediation?

From Dean Dad: No Pell for Remediation?

The 401(k) world

There has been some real tough reflection on tax expenditures recently. I have always seen 401(k) and IRA savings vehicles as being a better than average idea for using this approach. It's sure better than tax advantaging investment income, which is very interesting in the abstract but in the real world seems to flow to the best off.

But people are making some solid points about whether this is really a good idea or not. If they don't work to incentivize the right behavior on the part of either consumers or vendors than maybe they are not an ideal retirement savings approach.

James Kwak:

Matt Yglesias

The alternative, at this point, is social security. I am very sympathetic to arguments that assets are just claims and that providing for the elderly ultimately turns into a resource sharing problem. The difference appears to be that social security would divide the resources we put towards older adults more equitably than tax-advantaged savings plans do.

But people are making some solid points about whether this is really a good idea or not. If they don't work to incentivize the right behavior on the part of either consumers or vendors than maybe they are not an ideal retirement savings approach.

James Kwak:

The first is that they go overwhelmingly to people who don't need them -- like my wife and me. As two university professors living in Western Massachusetts, where the cost of living is low, we make more than we need to support our lifestyle. We max out our defined contribution plans every year, and because we're in a relatively high tax bracket (28%, I think), we save thousands of dollars a year on our taxes. This is the problem with most subsidies that are delivered as tax deductions. Their cash value depends on the amount you can deduct and on your marginal tax rate. In this case, fully 80 percent of retirement savings tax subsidies goes to households in the top income quintile. (See Toder, Harris, and Lim, Table 5.)

The second problem is that these tax incentives don't work. They don't cause people to save more. In my case, the amount we save is just our income minus our consumption, and our consumption isn't affected by the tax code. If there were no tax subsidy, we would save the same amount and just pay more in taxes. And it's not just us. A recent and widely discussed paper by Raj Chetty, John Friedman, Soren Leth-Petersen, Torben Heien Nielsen, and Tore Olsen looked at what happened when the Danish government reduced tax subsidies for retirement savings by rich people. The short answer is that decreases in retirement savings were almost perfectly matched by increases in non-retirement savings. The overall effect, they estimate, is that for every dollar in tax subsidies, total savings go up by one cent. The other ninety-nine cents is just a handout to people who would have saved anyway.

Matt Yglesias

Middle class retirement savings isn't like that. We know roughly how much people need to put away in order to retire with a standard of living they'll be comfortable with. And we definitely know what kind of investment vehicles are most appropriate for middle class savers. And we have abundant evidence that, left to their own devices, a very large share of middle class savers will make the wrong choices. What's more, because of the nature of the right choices it's obvious that the dominant business strategy for vendors of middle class investment products is to dedicate your time and energy to developing and marketing inferior products, since the essence of superior products in this field is that they're less remunerative.The most convincing part is the whole question of how 401(k) plans are designed to reduce consumer choice and the resulting incentive to offer inferior products. After all, the employer setting up the 401(k) has little incentive to make sure that difficult to spot fees don't eat up other people's money.

The alternative, at this point, is social security. I am very sympathetic to arguments that assets are just claims and that providing for the elderly ultimately turns into a resource sharing problem. The difference appears to be that social security would divide the resources we put towards older adults more equitably than tax-advantaged savings plans do.

On the bright side, all those elderly shut-ins won't have to worry about having their flights delayed

I won't belabor the point right now but one of the recurring underlying themes in the posts from both authors of this blog is the increasing difficulty with which information passes up the economic ladder and the extraordinary disconnect in perceptions that difficulty has caused.

This is not just a case of not knowing how the other half lives; it's not knowing how the other deciles live (or at least, how the deciles below you live). Thus a problem involving products and services used disproportionately by the upper and upper-middle class is given a high level of coverage and is addressed almost immediately while on the other end of the economic spectrum, important (sometimes vital) products and services are curtailed or even eliminated with little reaction from those unaffected.

Arthur Delaney writing for the Huffington Post:

This is not just a case of not knowing how the other half lives; it's not knowing how the other deciles live (or at least, how the deciles below you live). Thus a problem involving products and services used disproportionately by the upper and upper-middle class is given a high level of coverage and is addressed almost immediately while on the other end of the economic spectrum, important (sometimes vital) products and services are curtailed or even eliminated with little reaction from those unaffected.

Arthur Delaney writing for the Huffington Post:

Now McCormick is 70 years old and living alone in a one-bedroom apartment in a six-story building. Only about 40 of the building's 144 units are occupied. The parking lots are barren and the hallways are dingy with torn carpets. McCormick considers the building "spooky."

He's lived here since 2005, and for most of that time he has benefited from food charity every week day ... brought to him by Meals On Wheels volunteers. Since 1972 the Administration on Aging has provided federal funding for senior nutrition, and today volunteers from some 5,000 Meals On Wheels affiliates across the country distribute a million meals a day.

But federal funding for senior nutrition has been reduced by budget cuts known as sequestration, meaning less food for old people here and elsewhere. The White House has said the cuts would mean 4 million fewer meals for seniors this year, while the Meals On Wheels Association of America put the loss at 19 million meals. In general, the federal government subsidizes only a portion of the cost of every meal, so whether individual seniors will stop receiving food really depends on the circumstances of whatever local agency serves them.

Michele Daley, director of nutrition services at the Local Office on Aging, which serves Roanoke, Alleghany, Botetourt and Craig counties in Virginia, said the agency expects to receive $95,000 less in federal funds this year (it has an operating budget of $1 million). They're gradually reducing the number of people receiving daily meals from 650 to 600 as a result of the budget cuts. Already, the office has planned to stop handing out most emergency meals -- bags of shelf-stable items like canned beans distributed in advance of snowstorms and holidays. And they've instituted a waiting list.

"We've never had a waiting list," Daley said. "This is the first time ever and it's a direct result of sequestration."

After he learned about the cuts on the news, McCormick thought long and hard about whether he really needed the meals. He's got no car, and can't walk long distances, but sometimes he can get a ride to the grocery store and the food pantry, and he's got a small stockpile of canned goods sitting on a wooden desk in his living room.

"I've run into people who've been a whole lot worse off than I was," he said.

...

Many seniors would prefer to live independently in an apartment than dwindle away in a nursing home, and that's partly the point of bringing them food at home. It's also fiscally prudent: A Brown University study found the more states spend on meals, which are not expensive, the less they spend housing seniors in nursing homes, which costs much more.

...

Field did not drive to William McCormick's lonely apartment tower, and neither did any of Roanoke's other Meals On Wheels volunteers, at least not to visit McCormick. Last month, after taking stock of his own access to food and considering people less fortunate, he decided to drop out of the program.

"I thought about it for two or three days and I said, 'Right now my health's pretty good,' and so I just gave it up," he said. "I just couldn't bear the thought of me having something to eat and maybe somebody else needing it and they couldn't apply for it so I just voluntarily gave it up."

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Portion sizes

It has been a busy month but I want to go back to one of Mark's posts. Mark states:

What is more remarkable, to me, is how much things like meat serving sizes fit with modern dietary approaches. But I would be surprised if this advice was not very effective at weight control even today.

There are certainly things here that would seem strange here (make sure to get two pats of butter every day), but much of advice -- not overeating, watching salt, sugar and fat, satisfying cravings in moderation -- still seems fairly sound.Even today, dietary guidelines suggest getting some fat in your diet. So how much butter is in a pat of butter?

20 calories in 1 small pat of salted/unsalted butter (0.1 oz or 3g)For a 2000 calories diet, that is 2% of your daily energy intake. Now if you consider what was easy to preserve and likely to be widely available in 1950, this makes sense. Today we'd probably substitute nuts for the butter. But it would be challenging to find a nutritionist who had trouble with a garnish that was about 4-6 grams of fat/day.

What is more remarkable, to me, is how much things like meat serving sizes fit with modern dietary approaches. But I would be surprised if this advice was not very effective at weight control even today.

Reasons we value a college degree (aside from the obvious)

One of the things I find concerning about the MOOC debate is how simplistic many of the views are, both of college classes in particular and of college education in general. (Here is another one of my concerns.)

Over at Stumbling and Mumbling, Chris Dillow does a good job helping with the latter, discussing the less obvious ways that degrees can pay dividends (not sure about the last one though).

Over at Stumbling and Mumbling, Chris Dillow does a good job helping with the latter, discussing the less obvious ways that degrees can pay dividends (not sure about the last one though).

Nevertheless,we should ask: what function would universities serve in an economy where demand for higher cognitive skills is declining? There are many possibilities:I suspect that signaling is the main reason why increasingly many jobs require college degrees though they don't seem to involve any skills we would normally associate with college. HR departments spend a great deal of their time and energy narrowing applicant pools down to a manageable size. Degree requirements are a simple and easy to implement filter.

- A signaling device. A degree tells prospective employers that its holder is intelligent, hard-working and moderately conventional - all attractive qualities.

- Network effects. University teaches you to associate with the sort of people who might have good jobs in future, and might give you the contacts to get such jobs later.

- A lottery ticket.A degree doesn't guarantee getting a good job. But without one, you have no chance.

- Flexibility. A graduate can stack shelves, and might be more attractive as a shelf-stacker than a non-graduate. Beaudry and colleagues decribe how the falling demand for graduates has caused graduates to displace non-graduates in less skilled jobs.

- Maturation & hidden unemployment. 21-year-olds are more employable than 18-year-olds, simply because they are three years less foolish. In this sense, university lets people pass time without showing up in the unemployment data.

- Consumption benefits. University is a less unpleasant way of spending three years than work. And it can provide a stock of consumption capital which improves the quality of our future leisure. By far the most important thing I learnt at Oxford was a love of Hank Williams and Leonard Cohen.

Monday, April 29, 2013

A break from the Felix-bashing

I realize I've been hard on him lately, but it's worth taking a moment to remember that Felix Salmon is one of the best financial journalists out there, especially on the philanthropy beat:

A word of warning, I would not advise reading past the phrase "vision process" on a full stomach.

While the Cooper Union ethos never left the students or the faculty, however, it did seem to desert a significant chunk of the Board of Trustees and the administration. Starting as long ago as the early 1970s, the board started selling off the land bequeathed by Cooper, not to invest the proceeds in higher-yielding assets, but rather just to cover accumulated deficits. Cooper hated debt and deficits, but that hatred was not shared by later administrators, who would allow debts to accumulate — bad enough — until the only solution was to sell off the college’s patrimony, thereby reducing the resources available for future generations of students. If you visit Astor Place today, the intersection once dominated by the handsome Cooper Union building, the main thing you notice are two gleaming new glass-curtain-walled luxury buildings, one residential and one commercial, both constructed on land bought from Cooper Union.I started to quote more, but as startling and depressing as the details are, you really need to read the whole thing to get the full impact. It's an extraordinary story with particular significance to those following the tuition debates. While it would be a mistake to assume Cooper Union is completely representative, it is an enormously instructive example that seems to give us one more reason to question the cost disease theory.

Then, when you turn the corner and look at what hulks across the street from the main Cooper Union building, you can see where a huge amount of the money went: into a gratuitously glamorous and expensive New Academic Building, built at vast expense, with the aid of a $175 million mortgage which Cooper Union has no ability to repay.

A word of warning, I would not advise reading past the phrase "vision process" on a full stomach.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)