[I wrote most of this ages ago, but it took me so long to get the final draft done that it's now a seasonal post.]

My parents would tell the story of how, when I was four or five years old, I went up to them and asked somewhat tentatively, “Reindeer can't really fly, can they?” They admitted that no, reindeer couldn’t take flight. I thought about that for a moment and then asked, “There's not really a Santa Claus, is there?” From that point on, it was understood in our household that my mom and dad were providing the presents at Christmas.

I don’t remember that, but I do remember my first-grade teacher having to reassure what I now realize were some rather traumatized six and seven year olds that, no matter what their classmate had been telling them, there really was a Santa Claus.

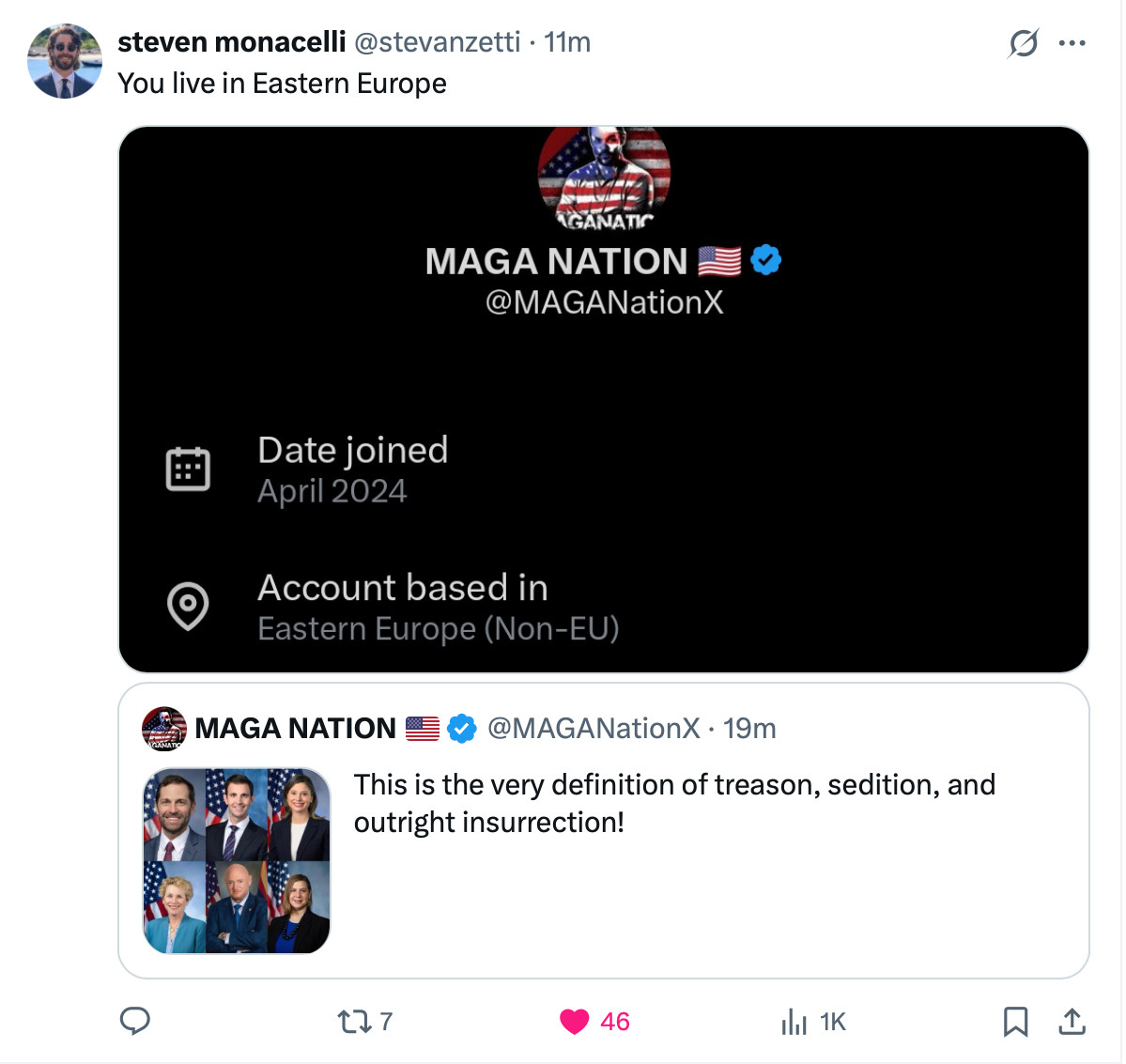

For a lot of us, the reindeer moment when it came to Elon Musk was the Hyperloop.

"A cross between a Concorde and a railgun and an air hockey table"

Going into 2013, my general impression of Musk, which was consistent with what I’d been hearing from researchers and engineers, was that he clearly wasn’t a real-life Tony Stark, but he was a smart guy who did his homework and understood the big picture. Then I heard about Musk's big idea for a new mode of transportation and that familiar nagging reindeer doubt began to form.

For starters, this was more or less explicitly an attack on High-Speed Rail in California which struck a jarring note coming from someone who had built his reputation largely around the issue of sustainability. It turned out to be just the first indication of Elon musk's profound hostility toward public transportation, one of the many wedges that would be driven between him and his supporters on the left.

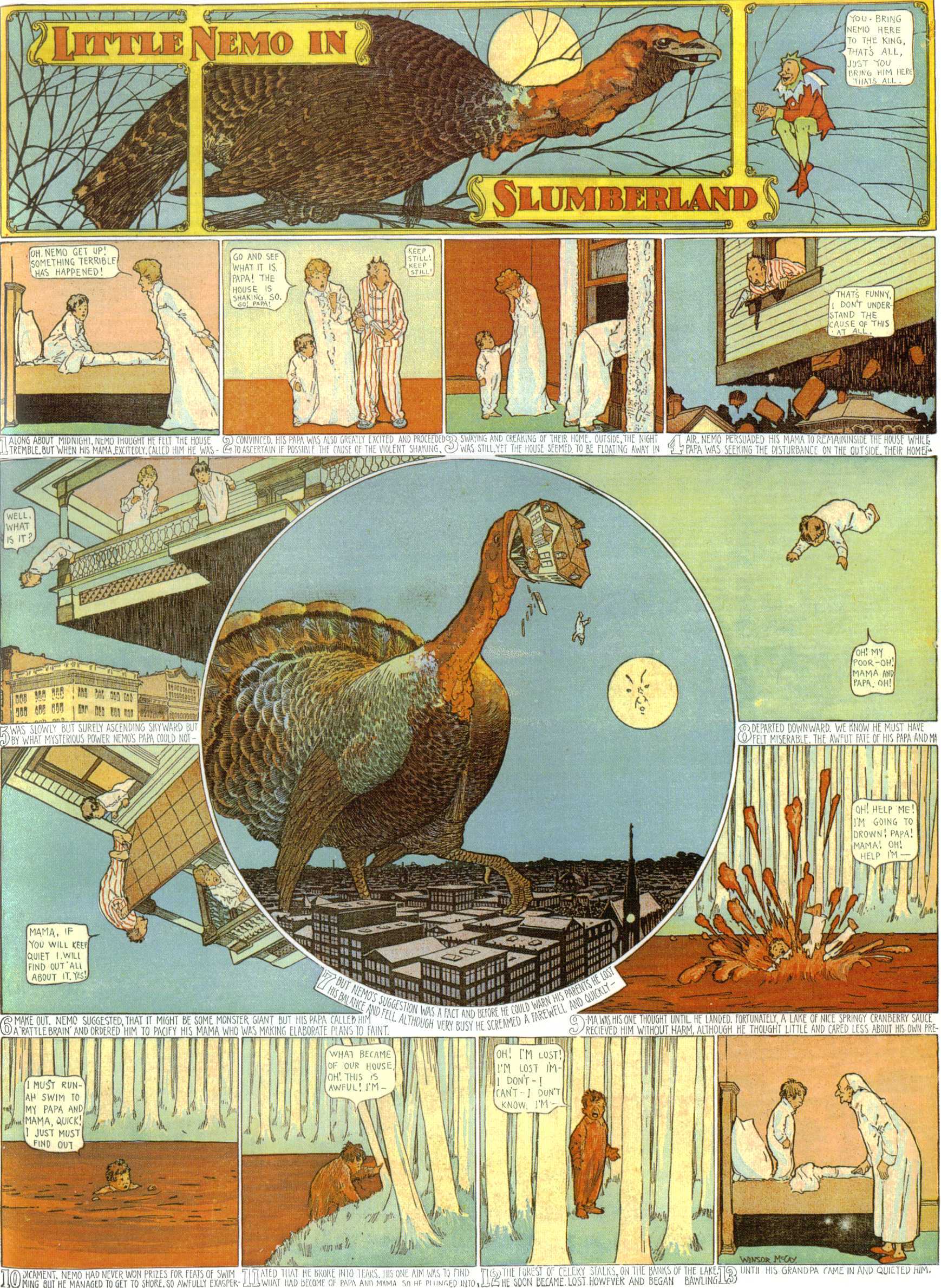

The main issue, however, was that the proposal was at once stunningly grandiose and incredibly stupid. We've had a decade now of Musk making delusional boasts and describing himself in Messianic terms, but for most of us, this was our first taste of the man's narcissism, made all the more striking by the fact that his "invention" was something that had occurred to thousands of people over the years- - it was even a standard element in science fiction -- but which was obviously unworkable if you gave it any serious thought.

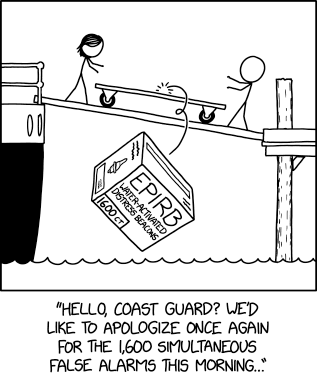

Putting aside the most absurd element of the original proposal, having a high-speed vactrain running on an air cushion (I will never tire of seeing actual engineers reactions when they hear about that part), anyone with common sense and the most basic grasp of engineering and construction could see a huge number of insurmountable flaws.

Civil engineers and transportation researchers immediately tore into Musk' s grand white paper and left virtually nothing standing. Though the rocket scientists at SpaceX had done their best to polish their boss's turd, they couldn't come up with any workable, let alone innovative solutions. There was literally nothing of value there.

The sheer quantity of flaws was so overwhelming that none of the critics even attempted a comprehensive take down. The cost projections were off by orders of magnitude. Most of the issues associated with constructing and maintaining a tube with a near vacuum extending hundreds of miles were ignored. Others were addressed in the silliest way possible (to deal with thermal expansion, the stations at either end would have to be put on rollers so they could move back and forth hundreds of yards). A breach in the tube caused by natural disaster, accident, or terrorist attack would cause catastrophic failure, shutting down the entire line, probably causing serious structural damage miles away from the site, and killing hundreds of people.

The other thing I noticed was how Musk’s fans were quietly, and perhaps even unconsciously, editing and revising what he said to make it more viable. His original pitch was for something that worked like (in his words) an air hockey table, a train that traveled on a cushion of air. This was part of the original proposal. It was in the white paper. It featured prominently in his early interviews. You really couldn't miss it.

But when actual proposals started coming out promising to make Elon Musk's idea a reality, every single one was for a maglev system. As far as I can tell, out of the hundred plus million dollars that have gone into these projects, literally ot a penny has gone into the technology Musk proposed. As silly and impractical as their designs were, they were still far more workable than what they claimed to be building.