There are some exceptions (particularly from Dennis O'Neil), on the whole though...

The Brave and the Bold #94

February-March 1971

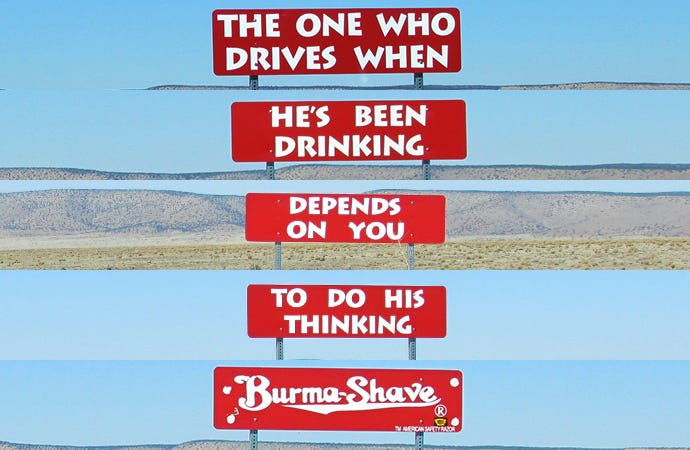

The trope of the youth movement rising up to suppress, imprison, or straight out massacre everyone over thirty-five was extremely common in the late sixties and early seventies and even made it to the covers of mainstream comics. The subgenre is largely forgotten now, but the anxiety it reflected had a great deal to do with the rise of Reagan a few years later.

The title of this comic was an obvious at the time reference to arguably the definitive youth paranoia movie.

Monday, March 7, 2022

This was going to be part of an upcoming post but I decided it worked better freestanding.

Back in the late sixties there was a surprising popular genre of apocalyptic dystopias inspired by fears of the youth movement. Countless examples in episodic television (three or four from Star Trek alone). The 1967 novel Logan’s Run (but not the 1976 movie which dropped the political aspects of the story). Arguably films If and Clockwork Orange (though in this case, not the book, which is more a part of the post-war panic over juvenile delinquency). Corman’s Gas-s-s-s. Certainly others I’m forgetting.

Though not the best in the bunch, the most representative was Wild in the Streets.

Wild in the Streets figures prominently in Pauline Kael's essay "Trash, Art, and the Movies": [emphasis added]

There is so much talk now about the art of the film that we may be in danger of forgetting that most of the movies we enjoy are not works of art. The Scalphunters, for example, was one of the few entertaining American movies this past year, but skillful though it was, one could hardly call it a work of art — if such terms are to have any useful meaning. Or, to take a really gross example, a movie that is as crudely made as Wild in the Streets — slammed together with spit and hysteria and opportunism — can nevertheless be enjoyable, though it is almost a classic example of an unartistic movie. What makes these movies — that are not works of art — enjoyable? The Scalphunters was more entertaining than most Westerns largely because Burt Lancaster and Ossie Davis were peculiarly funny together; part of the pleasure of the movie was trying to figure out what made them so funny. Burt Lancaster is an odd kind of comedian: what’s distinctive about him is that his comedy seems to come out of his physicality. In serious roles an undistinguished and too obviously hard-working actor, he has an apparently effortless flair for comedy and nothing is more infectious than an actor who can relax in front of the camera as if he were having a good time. (George Segal sometimes seems to have this gift of a wonderful amiability, and Brigitte Bardot was radiant with it in Viva Maria!) Somehow the alchemy of personality in the pairing of Lancaster and Ossie Davis — another powerfully funny actor of tremendous physical presence — worked, and the director Sydney Pollack kept tight control so that it wasn’t overdone.

And Wild in the Streets? It’s a blatantly crummy-looking picture, but that somehow works for it instead of against it because it’s smart in a lot of ways that better-made pictures aren’t. It looks like other recent products from American International Pictures but it’s as if one were reading a comic strip that looked just like the strip of the day before, and yet on this new one there are surprising expressions on the faces and some of the balloons are really witty. There’s not a trace of sensitivity in the drawing or in the ideas, and there’s something rather specially funny about wit without any grace at all; it can be enjoyed in a particularly crude way — as Pop wit. The basic idea is corny — It Can’t Happen Here with the freaked-out young as a new breed of fascists — but it’s treated in the paranoid style of editorials about youth (it even begins by blaming everything on the parents). And a cheap idea that is this current and widespread has an almost lunatic charm, a nightmare gaiety. There’s a relish that people have for the idea of drug-taking kids as monsters threatening them — the daily papers merging into Village of the Damned. Tapping and exploiting this kind of hysteria for a satirical fantasy, the writer Robert Thom has used what is available and obvious but he’s done it with just enough mockery and style to make it funny. He throws in touches of characterization and occasional lines that are not there just to further the plot, and these throwaways make odd connections so that the movie becomes almost frolicsome in its paranoia (and in its delight in its own cleverness).

It's easy to be dismissive of these fears fifty plus years later, but the revolutionary rhetoric of the movement was often extreme and was punctuated by the occasional bombing, bank robbery, etc.

But probably the biggest mistake people made when predicting the impact of the sixties youth movement was taking them at their word, believing that their commitment to radicalism (or even liberalism) would outlast the end of the Vietnam War. The post-war generation would change the country, but I doubt anyone in 1969 would have guessed how.