Given the number of readers with relevant experience in this field, perhaps someone would like to weigh in on this.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, December 8, 2017

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Agon

I'm a big fan of abstract strategy games, particularly those played on hexagonally-tiled boards (such as the ones you can purchase here). One of my favorites is Agon. It's a challenging but easy to learn game that's deserves a much bigger following. Here is the write-up I did of the rules a few years ago.

Agon may be the oldest abstract strategy game played on a 6 by 6 by 6 hexagonally tiled board, first appearing as early as the late Eighteenth Century in France. The game reached it greatest popularity a hundred years later when the Victorians embraced it for its combination of simple moves and complex strategy.

The Pieces: Each player has one queen and six pawns a.k.a. guards placed in the pattern indicated below

The Objective: To place your queen in the center hexagon and surround her with all six of her guards.(below)

Moves: Think of the Agon board as a series of concentric circles (see above). Pieces can move one space at a time either in the same ring or the ring closer to the center. In the figure on the left, a piece on a hexagon marked 4 could move to an adjacent hexagon marked either 4 or 3. Only the queen is allowed to move into the center hexagon. The figure below shows possible moves.

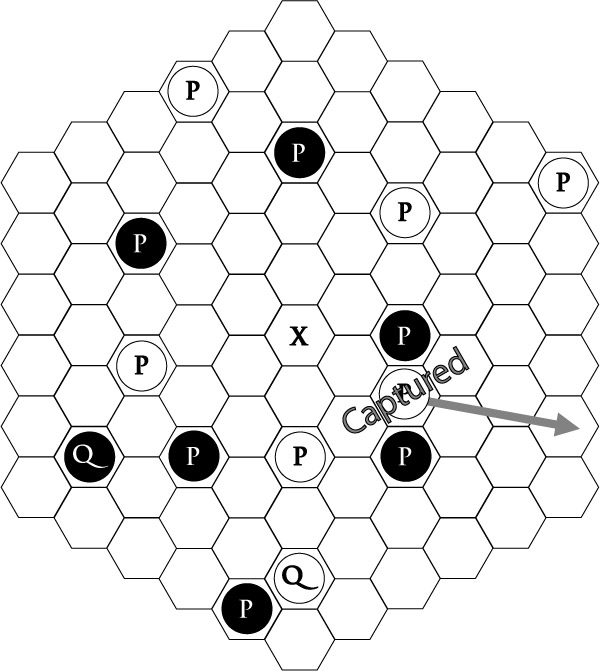

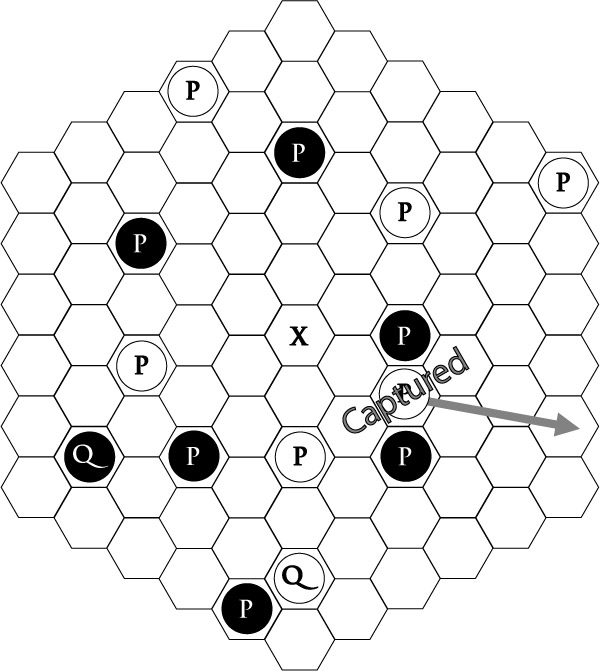

Capturing: A piece is captured when there are two enemy pieces on either side of it. The player with the captured piece must use his or her next move to place the captured piece on the outside hexagon.

If the captured piece is a guard, the player whose piece was captured can choose where on the outer hex to place the piece. If the piece is a queen, the player who made the capture decides where the queen should go.

If more than one piece is captured in one turn, the player whose pieces were captured must move them one turn at a time.

If a player surrounds the center hexagon with guards without getting the queen into position, that player forfeits the game.

Agon may be the oldest abstract strategy game played on a 6 by 6 by 6 hexagonally tiled board, first appearing as early as the late Eighteenth Century in France. The game reached it greatest popularity a hundred years later when the Victorians embraced it for its combination of simple moves and complex strategy.

The Pieces: Each player has one queen and six pawns a.k.a. guards placed in the pattern indicated below

The Objective: To place your queen in the center hexagon and surround her with all six of her guards.(below)

Moves: Think of the Agon board as a series of concentric circles (see above). Pieces can move one space at a time either in the same ring or the ring closer to the center. In the figure on the left, a piece on a hexagon marked 4 could move to an adjacent hexagon marked either 4 or 3. Only the queen is allowed to move into the center hexagon. The figure below shows possible moves.

Capturing: A piece is captured when there are two enemy pieces on either side of it. The player with the captured piece must use his or her next move to place the captured piece on the outside hexagon.

If the captured piece is a guard, the player whose piece was captured can choose where on the outer hex to place the piece. If the piece is a queen, the player who made the capture decides where the queen should go.

If more than one piece is captured in one turn, the player whose pieces were captured must move them one turn at a time.

If a player surrounds the center hexagon with guards without getting the queen into position, that player forfeits the game.

Dilation and contraction.

Our standard narrative is deeply invested in the idea that progress is ever accelerating and that we are always on the cusp of an unimaginable leap forward. One of the favorite devices used to sustain this belief is dilation/contraction. The rate of technological change and its impact on society in the past is underestimated (particularly when describing the periods of the late 19th/early 20th centuries and the postwar era) while the current rate of change is overestimated, often wildly so when it comes to near-future predictions.

The following by Jim Hoagland is a good example.

It is essential to note that, despite decades of serious and aggressive research and development, none of these technologies currently exist (at least not at the levels implied here) and, with the exception of autonomous vehicles, they probably won't exist a decade from now. Even with AVs, ruling the road will probably take decades unless we start heavily regulating non-autonomous cars.

(As we've pointed out before, there is an important distinction between driverless cars and driverless trucks. While both are coming, the current economic case for autonomous trucking makes far more sense and the technological challenge of driving a relatively small number of routes is considerably less. Long haul truck driving has the potential to go away quite suddenly.)

It's true that outside factors often slowed implementation in fields like electricity in the past. Factories had to be reconfigured. Power lines had to be laid. This meant that the adoption of certain technologies was delayed, particularly in certain localities, but even with this, the rate of technological change around the turn-of-the-century and, to a somewhat lesser extent, in the postwar era, was stunning.

More importantly in this case, (barring the special case where a new technology can be uploaded without any kind of change or upgrade of hardware) the same basic issues still apply. Even with AV's, there's still development time, infrastructure and adoption to consider.

The day is coming when you'll be able to say an address into your phone and have your car on its way without ever leaving the comfort of your couch. The prognosis for Hoagland's other just-around-the-corner innovations is considerably less promising. There are daunting problems involved with using AI to take over complex, badly understood tasks that largely lack reliable and agreed-upon metrics of success. While as for flying cars, the obstacles are huge and we have a history of failed promises going back literally a century. Just because some compulsive liar whose primary accomplishment has been getting gullible venture capitalists to write him ginormous checks makes this particular promise doesn't mean you should report it in the pages of the Washington Post as a done deal.

But even allowing for the vanishingly small chance that all of these things do come to pass roughly in the time frame given, we would still be nowhere near the level of technological change that people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had to adapt to in virtually every aspect of their world, from day-to-day living to industry to transportation to mass media to telecommunications to medicine to agriculture and to all the others that I have invariably left off the list.

The following by Jim Hoagland is a good example.

Driverless cars and trucks rule the road, while robots “man” the factories. Super-smartphones hail Uber helicopters or even planes to fly their owners across mushrooming urban areas. Machines use algorithms to teach themselves cognitive tasks that once required human intelligence, wiping out millions of managerial, as well as industrial, jobs.

These are visions of a world remade — for the most part, in the next five to 10 years — by technological advances that form a fourth industrial revolution. You catch glimpses of the same visions today not only in Silicon Valley but also in Paris think tanks, Chinese electric-car factories or even here at the edge of the Sahara.

Technological disruption in the 21st century is different. Societies had years to adapt to change driven by the steam engine, electricity and the computer. Today, change is instant and ubiquitous. It arrives digitally across the globe all at once.

It is essential to note that, despite decades of serious and aggressive research and development, none of these technologies currently exist (at least not at the levels implied here) and, with the exception of autonomous vehicles, they probably won't exist a decade from now. Even with AVs, ruling the road will probably take decades unless we start heavily regulating non-autonomous cars.

(As we've pointed out before, there is an important distinction between driverless cars and driverless trucks. While both are coming, the current economic case for autonomous trucking makes far more sense and the technological challenge of driving a relatively small number of routes is considerably less. Long haul truck driving has the potential to go away quite suddenly.)

It's true that outside factors often slowed implementation in fields like electricity in the past. Factories had to be reconfigured. Power lines had to be laid. This meant that the adoption of certain technologies was delayed, particularly in certain localities, but even with this, the rate of technological change around the turn-of-the-century and, to a somewhat lesser extent, in the postwar era, was stunning.

More importantly in this case, (barring the special case where a new technology can be uploaded without any kind of change or upgrade of hardware) the same basic issues still apply. Even with AV's, there's still development time, infrastructure and adoption to consider.

The day is coming when you'll be able to say an address into your phone and have your car on its way without ever leaving the comfort of your couch. The prognosis for Hoagland's other just-around-the-corner innovations is considerably less promising. There are daunting problems involved with using AI to take over complex, badly understood tasks that largely lack reliable and agreed-upon metrics of success. While as for flying cars, the obstacles are huge and we have a history of failed promises going back literally a century. Just because some compulsive liar whose primary accomplishment has been getting gullible venture capitalists to write him ginormous checks makes this particular promise doesn't mean you should report it in the pages of the Washington Post as a done deal.

But even allowing for the vanishingly small chance that all of these things do come to pass roughly in the time frame given, we would still be nowhere near the level of technological change that people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had to adapt to in virtually every aspect of their world, from day-to-day living to industry to transportation to mass media to telecommunications to medicine to agriculture and to all the others that I have invariably left off the list.

Wednesday, December 6, 2017

Insert obligatory what's-a-newspaper? joke here

Another small piece (or, more accurately, medium-size piece of a big piece) of the late 19th/early 20th century technology spike.

Media innovation was a big part of this story, not in the same league as internal combustion and electricity, but still a big player marked with a number of stunning advances.Most of the attention here tends to go to the then completely new developments such as recorded sound and moving pictures, but in terms of impact, advances in printing may have had more of an effect on the period.

I have been going through some old Scientific Americans for material and came across this excellent example from 1896. In the middle of the century, putting out a major metropolitan daily required the equivalent of a medium-size, well staffed factory.

By the last decade of the century, the presses were five times as fast, a fraction of the size, and largely automated.

This and other technological innovations (such as color printing) made publications like the Strand magazine and journalistic events like the Hearst/Pulitzer circulation wars and the rise of the comic strips possible. All of this had an enormous impact on American culture and politics.

Media innovation was a big part of this story, not in the same league as internal combustion and electricity, but still a big player marked with a number of stunning advances.Most of the attention here tends to go to the then completely new developments such as recorded sound and moving pictures, but in terms of impact, advances in printing may have had more of an effect on the period.

I have been going through some old Scientific Americans for material and came across this excellent example from 1896. In the middle of the century, putting out a major metropolitan daily required the equivalent of a medium-size, well staffed factory.

By the last decade of the century, the presses were five times as fast, a fraction of the size, and largely automated.

This and other technological innovations (such as color printing) made publications like the Strand magazine and journalistic events like the Hearst/Pulitzer circulation wars and the rise of the comic strips possible. All of this had an enormous impact on American culture and politics.

Tuesday, December 5, 2017

Non-belated Tuesday Tweets

You'd think coming out against women's suffrage would be Thiel's low point, but he keeps exceeding expectations. https://t.co/Uvs1G0IwGV— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 23, 2017

For years I've been meaning to write something about new forms of price discrimination undermining price discovery.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 25, 2017

Looks like I shouldn't have dragged my feet. https://t.co/TvtiaDFlT0

Interesting how these articles always say we need to develop something that sounds exactly like a CLEP without acknowledging we already have a program in place. It's almost as if focusing on making better use of existing tools isn't sexy (or profitable). https://t.co/ZFw1nEZ5Rx— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 27, 2017

Excellent work from Matt Lewis, though I'd still frame it more as "drinking from the wrong pipe."https://t.co/TmmIZhw3xB https://t.co/iJ3Xmzeple— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 28, 2017

The expression back in Arkansas was "towns that Walmart killed twice," first by opening a store that drove local merchants out of business, then by closing met store and forcing residents to drive to the next town. https://t.co/0yAgJCOuPA— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 4, 2017

Monday, December 4, 2017

Want to see a 19th Century polar exploration balloon? Thought so...

Besancon and Hermite never actually made the trip, of course, but, damn, the illustrations are cool.

Friday, December 1, 2017

Yes, I know I've reposted this, but it keeps getting more relevant

As we were saying in August (point 2.2 to be precise)https://t.co/5k86uQjWOz— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 1, 2017

Republicans Are Building Themselves a Political Trap with ‘Tax Reform’ https://t.co/ChaPJSaxqb via @TPM

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

The Republicans' 3 x 3 existential threat

I've argued previously that Donald Trump presents an existential threat to the Republican Party. I know this can sound overheated and perhaps even a bit crazy. There are few American institutions as long-standing and deeply entrenched as are the Democratic and Republican parties. Proposing that one of them might not be around 10 years from now beggars the imagination and if this story started and stopped with Donald Trump, it would be silly to suggest we were on the verge of a political cataclysm.But, just as Trump's rise did not occur in a vacuum, neither will his fall. We discussed earlier how Donald Trump has the power to drive a wedge between the Republican Party and a significant segment of its base [I wrote this before the departure of Steve Bannon. That may diminish Trump's ability to create this rift but I don't think it reduces the chances of the rift happening. – – M.P.]. This is the sort of thing that can profoundly damage a political party, possibly locking it into a minority status for a long time, but normally the wound would not be fatal. These, however, are not normal times.

The Republican Party of 2017 faces a unique combination of interrelated challenges, each of which is at a historic level and the combination of which would present an unprecedented threat to this or any US political party. The following list is not intended to be exhaustive, but it hits the main points.

The GOP currently has to deal with extraordinary political scandals, a stunningly unpopular agenda and daunting demographic trends. To keep things symmetric and easy to remember, let's break each one of these down to three components (keeping in mind that the list may change).

With the scandals:

1. Money – – Even with the most generous reading imaginable, there is no question that Trump has a decades long record of screwing people over, skirting the law, and dealing with disreputable and sometimes criminal elements. At least some of these dealings have been with the Russian mafia, oligarchs, and figures tied in with the Kremlin which leads us to…

2. The hacking of the election – – This one is also beyond dispute. It happened and it may have put Donald Trump into the White House. At this point, we have plenty of quid and plenty of quo; if Mueller can nail down pro, we will have a complete set.

3. And the cover-up – – As Josh Marshall and many others have pointed out, the phrase "it's not the crime; it's the cover-up" is almost never true. That said, coverups can provide tipping points and handholds for investigators, not to mention expanding the list of culprits.

With the agenda:

1. Health care – – By some standards the most unpopular major policy proposal in living memory that a party in power has invested so deeply in. Furthermore, the pushback against the initiative has essentially driven congressional Republicans into hiding from their own constituents for the past half year. As mentioned before, this has the potential to greatly undermine the relationship between GOP senators and representatives and the voters.

2. Tax cuts for the wealthy – – As said many times, Donald Trump has a gift for making the subtle plain, the plain obvious, and the obvious undeniable. In the past, Republicans were able to get a great deal of upward redistribution of the wealth past the voters through obfuscation and clever branding, but we have reached the point where simply calling something "tax reform" is no longer enough to sell tax proposals so regressive that even the majority of Republicans oppose them.

3. Immigration (subject to change) – – the race for third place in this list is fairly competitive (education seems to be coming up on the outside), but the administration's immigration policies (which are the direct result of decades of xenophobic propaganda from conservative media) have already done tremendous damage, caused great backlash, and are whitening the gap between the GOP and the Hispanic community, which leads us to…

Demographics:

As Lindsey Graham has observed, they simply are not making enough new old white men to keep the GOP's strategy going much longer, but the Trump era rebranding of the Republican Party only exacerbates the problems with women, young people, and pretty much anyone who isn't white.

Maybe I am missing a historical precedent here, but I can't think of another time that either the Democrats or the Republicans were this vulnerable on all three of these fronts. This does not mean that the party is doomed or even that, with the right breaks, it can't maintain a hold on some part of the government. What it does mean is that the institution is especially fragile at the moment. A mortal blow may not come, but we can no longer call it unthinkable.

Lots of threads converging on this one

And all of them tremendously important. Corruption and regulatory capture. An almost mystical faith in the magic of markets and private-enterprise approaches (even if they end up being all but completely government-subsidized). An inexhaustible tolerance for concentration of wealth and power. Internalized Randianism complete with the belief that the rest of us owe a debt to the rich and powerful that we can never fully repay. Regulatory capture and occasionally good old-fashioned corruption.

Thank God for John Oliver.

Thank God for John Oliver.

Thursday, November 30, 2017

I'm running behind again so...

Here are two beautiful French planes from 1909. Back tomorrow with actual prose.

And a few impressive airships.

And a few impressive airships.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Belated Tuesday Tweets

“Newsworthy” implies “demands coverage,” not “deserves platform.”— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 13, 2017

Under its existing model, Uber's competitive advantage is mainly based on cheap nonunion labor providing its own vehicles. Under this model, Uber has no special advantage while competitors from Amazon to Google to car rental companies to auto manufacturers are better positioned.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 13, 2017

Josh missed the most important point, Forget racist, conspiracy theorist and fabulist. Cernovich first came to fame through the men's rights movement. Misogynists have now weaponized the backlash against harassment.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 21, 2017

True, but those decisions were made before false balance and Clinton derangement syndrome helped put Trump in the WH. This shows the NYT has learned nothing from its mistakes. @jayrosen_nyu— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 13, 2017

Of course, if the New York Times had followed the Washington Post's lead instead of doubling down on false balance, we might not have a situation they all need to rise to.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 20, 2017

Substitute 50s and Russian for 80s and Japanese and work in Sputnik...https://t.co/JdzsgDyDNX— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) November 22, 2017

Kruzno

Despite the pieces (I decided to go with something off the shelf for the prototype), it's not a chess variant. Instead, it's a capture-and-evade abstract strategy game where the rank of the pieces is non-transitive. The rules are simple enough for a small child to play but challenging enough to keep reasonably competent chess players on their toes. It is also the official game of a small village in Slovakia, but that's a story for another time.

Between now and Christmas, I'll be writing some posts on game design and possibly sharing some thoughts and cautionary tales about jumping into a small business with no relevant experience. In the meantime, I still have some of that first run up for sale on Amazon. Go by and check it out.

Monday, November 27, 2017

Another Tesla article from the Scientific American archives (along with some very cool train pictures).

19th Century drawing of a Geissler tubes.

This story mainly stands on its own but there are a couple points I want to emphasize. First, it's a nice example of that distinctive Tesla combination: important innovator; savvy showmen; extravagantly over-promising flake. That's not just something that shows in retrospect; you can see it coming through contemporary accounts. Sober observers were well aware of all of these facets. The man was capable of amazing advances; he also reported getting messages from Mars.

I also like the way the story knocks down a false but persistent trope. There's a tendency to treat earlier generations as innocent and unimaginative, often oblivious to the extraordinary events that were starting to unfold. Call it the "little did they imagine" genre. The trouble is it's almost entirely wrong. Particularly in America, people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw themselves as living in a wondrous time and they tended to greet new developments with great excitement, if anything, often overestimating the degree to which their world was about to change.

Reading through these old articles, one thing that strikes me is that wildly ambitious ideas were not accepted unskeptically, but they weren't treated dismissively either. People seemed to get that an idea could fail miserably and still be of great value.

This story mainly stands on its own but there are a couple points I want to emphasize. First, it's a nice example of that distinctive Tesla combination: important innovator; savvy showmen; extravagantly over-promising flake. That's not just something that shows in retrospect; you can see it coming through contemporary accounts. Sober observers were well aware of all of these facets. The man was capable of amazing advances; he also reported getting messages from Mars.

I also like the way the story knocks down a false but persistent trope. There's a tendency to treat earlier generations as innocent and unimaginative, often oblivious to the extraordinary events that were starting to unfold. Call it the "little did they imagine" genre. The trouble is it's almost entirely wrong. Particularly in America, people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw themselves as living in a wondrous time and they tended to greet new developments with great excitement, if anything, often overestimating the degree to which their world was about to change.

Reading through these old articles, one thing that strikes me is that wildly ambitious ideas were not accepted unskeptically, but they weren't treated dismissively either. People seemed to get that an idea could fail miserably and still be of great value.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)