Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Saturday, November 24, 2012

"Lance Armstrong And The Business Of Doping"

This Planet Money story is the first (and will probably be the last) account of the Armstrong scandal that has held my interest. It also changed my what's-the-big-deal attitude.

To have one $8 billion dollar writedown, Ms. Whitman, may be regarded as a misfortune. To have two looks like carelessness.

Ryan McCarthy in Counterparties:

HP has become the place where synergies go to die. In its earnings release today, HP said it has taken an $8.8 billion writedown, caused by what it calls “serious accounting improprieties” at Autonomy, a software company it acquired for $11 billion in August 2011. This, as David Benoit notes, is HP’s second acquisition-related $8 billion writedown of the year.I love the phrase "flexible definition."

HP is furiously pointing fingers: in a statement, the company said there was a “willful effort on behalf of certain former Autonomy employees to inflate the underlying financial metrics”. And CEO Meg Whitman told analysts that Deloitte had signed off on Autonomy’s accounts, with KPMG signing off on Deloitte. Still, only $5 billion of this quarter’s write down came from Autonomy’s accounting; the rest came from those pesky “headwinds against anticipated synergies and marketplace performance”.

There’s a strong case that HP should have smelled a rat. Bryce Elder points to “a decade’s worth of research questioning Autonomy’s revenue recognition, organic growth and seemingly flexible definition of a contract sale”. Then there’s the scathing statement which came about a month after the HP sale, in which Oracle revealed that it too had looked at Autonomy, but considered the company’s $6 billion market value to be “extremely over-priced”. Lynch, for his part, says that he was “ambushed” by the allegations.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Introducing "You Do the Math"

As Joseph mentioned earlier, I have a new blog up called You Do the Math focusing on ideas for teaching primary and secondary math. There's going to be a fair amount of cross-posting with this blog but I wanted a second outlet because:

1. I have a decade's worth of tips, exercises, lesson plans, test ideas, games, and puzzles for math teachers, much of which wouldn't be of much interest to most of the readers of this site.

2. I couldn't see the typical fifth grade teacher slogging through posts on the economics of health care and the potential for selection effects in polling and the rest of the analytic esoterica you'll find here.

3. I had some ideas I wanted to play around with. Since so many of the teaching posts aren't time sensitive, I'm using the scheduling function to keep a steady stream of content flowing. Many of the posts will be short and or recycled but I've already scheduled at least one a week for the next five months. When I get to six months I plan to go back to the beginning and start putting up a second post for each week. It will be interesting to so what the effect is on traffic, page rank, etc.

4. Pauline Kael talked about the way writing a regular column helped her discipline and organize her thinking about movies. I believe a blog can serve much the same function in other areas.

I've already got one up that talks about using codes to introduce numberlines and tables and another that shows how you can estimate pi by seeing how many times randomly selected points fall within a given radius and I have about two dozen more posts sitting in the queue. If this sort of thing sounds interesting to you, check it out and if you know of anyone who might have use for this, please pass it on.

Thanks,

Mark

1. I have a decade's worth of tips, exercises, lesson plans, test ideas, games, and puzzles for math teachers, much of which wouldn't be of much interest to most of the readers of this site.

2. I couldn't see the typical fifth grade teacher slogging through posts on the economics of health care and the potential for selection effects in polling and the rest of the analytic esoterica you'll find here.

3. I had some ideas I wanted to play around with. Since so many of the teaching posts aren't time sensitive, I'm using the scheduling function to keep a steady stream of content flowing. Many of the posts will be short and or recycled but I've already scheduled at least one a week for the next five months. When I get to six months I plan to go back to the beginning and start putting up a second post for each week. It will be interesting to so what the effect is on traffic, page rank, etc.

4. Pauline Kael talked about the way writing a regular column helped her discipline and organize her thinking about movies. I believe a blog can serve much the same function in other areas.

I've already got one up that talks about using codes to introduce numberlines and tables and another that shows how you can estimate pi by seeing how many times randomly selected points fall within a given radius and I have about two dozen more posts sitting in the queue. If this sort of thing sounds interesting to you, check it out and if you know of anyone who might have use for this, please pass it on.

Thanks,

Mark

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Blog list updated

The blog roll has had a fall cleaning. I removed a few blogs that were really interesting but which had not been updated for months or years. I added two new blogs: Mark Palko's new math teaching blog (which may occasionally cross post) and Mark Thoma's Economist's View (for which it is past time we added it).

Happy Thanksgiving, all!

Toys for Tots -- reprinted, slightly revised

A good Christmas can do a lot to take the edge off of a bad year both for children and their parents (and a lot of families are having a bad year). It's the season to pick up a few toys, drop them by the fire station and make some people feel good about themselves during what can be one of the toughest times of the year.

If you're new to the Toys-for-Tots concept, here are the rules I normally use when shopping:

The gifts should be nice enough to sit alone under a tree. The child who gets nothing else should still feel that he or she had a special Christmas. A large stuffed animal, a big metal truck, a large can of Legos with enough pieces to keep up with an active imagination. You can get any of these for around twenty or thirty bucks at Wal-Mart or Costco;*

Shop smart. The better the deals the more toys can go in your cart;

No batteries. (I'm a strong believer in kid power);**

Speaking of kid power, it's impossible to be sedentary while playing with a basketball;

No toys that need lots of accessories;

For games, you're generally better off going with a classic;

No movie or TV show tie-ins. (This one's kind of a personal quirk and I will make some exceptions like Sesame Street);

Look for something durable. These will have to last;

For smaller children, you really can't beat Fisher Price and PlaySkool. Both companies have mastered the art of coming up with cleverly designed toys that children love and that will stand up to generations of energetic and creative play.

*I previously used Target here, but their selection has been dropping over the past few years and it's gotten more difficult to find toys that meet my criteria.

** I'd like to soften this position just bit. It's okay for a toy to use batteries, just not to need them. Fisher Price and PlaySkool have both gotten into the habit of adding lights and sounds to classic toys, but when the batteries die, the toys live on, still powered by the energy of children at play.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Bitter Harvest

Just in time for Thanksgiving.

From Marketplace:

From Marketplace:

Michael Hogan, CEO of A.D. Makepeace, a large cranberry grower based in Wareham, says for now cranberries are still a viable crop in Massachusetts. But climate change is making it much tougher to grow there.I know we've been over this before, but it gets harder and harder to see how a cost/benefit analysis of climate change don't support immediate implementation of a carbon tax.or something similar.

"We're having warmer springs, we're having higher incidences of pests and fungus and we're having warmer falls when we need to have cooler nights," Hogan says.

Those changing conditions are costing growers like Makepeace money. The company has to use more water to irrigate in the hotter summers, and to cover the berries in spring and fall to protect them from frosts.

They're also spending more on fuel to run irrigation pumps, and have invested heavily in technology to monitor the bogs more closely. It's also meant more fungicides and fruit rot.

"Because of the percentage of rot that was delivered to Ocean Spray, they paid us $2 a barrel less," Hogan says. "We delivered 370,000 barrels last year. So you're talking about millions of dollars."

Cranberries also need a certain number of "chilling hours" to ensure that deep red color. Glen Reid, assistant manager of cranberry operations for A.D. Makepeace, says that's a problem as well.

"The berries actually need cold nights to color up," Reid says. "Last year we had a big problem with coloring up the berries. We had a lot more white berries."

Some growers in the Northeast have already moved some cranberry production to chillier climates, like eastern Canada. Ocean Spray has started growing cranberries on a new farm in the province of New Brunswick.

Makepeace's Hogan is even considering Chile, which apparently has a favorable climate for growing the North American berry.

Economics: a new definition?

Is it fair to quote the definition of economics from the blurb for a book? If so, consider this definition in the blurb for Emily Oster's new book:

None of this mean that Emily shouldn't write this book. My own read on the alcohol and pregnancy angle is that the current advice does seem to be based on an excess of caution. But it seems odd to argue that being an economist is the key piece here. Jumping fields is fine and can often lead to amazing insights, but maybe we should call this shifting of fields what it is rather than expanding the definition of economics to make it less meaningful?

When Oster was expecting her first child, she felt powerless to make the right decisions for her pregnancy. How doctors think and what patients need are two very different things. So Oster drew on her own experience and went in search of the real facts about pregnancy using an economist’s tools. Economics is not just a study of finance. It’s the science of determining value and making informed decisions. To make a good decision, you need to understand the information available to you and to know what it means to you as an individual.So, when applied to a medical topic (like pregnancy) how does this differ from evidence based medicine? Should I be calling myself an economist?

None of this mean that Emily shouldn't write this book. My own read on the alcohol and pregnancy angle is that the current advice does seem to be based on an excess of caution. But it seems odd to argue that being an economist is the key piece here. Jumping fields is fine and can often lead to amazing insights, but maybe we should call this shifting of fields what it is rather than expanding the definition of economics to make it less meaningful?

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

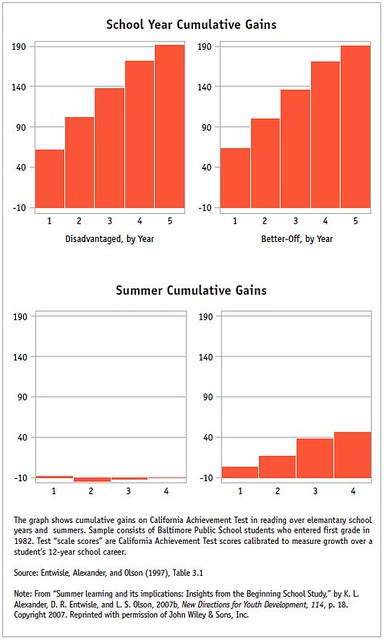

Depressing education chart of the day

Mike the Mad Biologist points us to this one.

From Karl Alexander (John Dewey Professor of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University):

UPDATE:

This seems like a good time to remind everyone about some of the other previously mentioned challenges these kids face:We discovered that about two-thirds of the ninth-grade academic achievement gap between disadvantaged youngsters and their more advantaged peers can be explained by what happens over the summer during the elementary school years.Mike goes on to point out the obvious question this raises about the fire-the-teachers approach to education reform.

I also want to point out that the higher performing group isn’t necessarily high income, but simply better off. In the context of the Baltimore City school system, that usually means solidly middle class, with parents who are likely to have gone to college versus dropping out.

Statistically, lower income children begin school with lower achievement scores, but during the school year, they progress at about the same rate as their peers. Over the summer, it’s a dramatically different story. During the summer months, disadvantaged children tread water at best or even fall behind. It’s what we call “summer slide” or “summer setback.” But better off children build their skills steadily over the summer months. The pattern was definite and dramatic. It was quite a revelation.

Hart and Risley also found that, in the first four years after birth, the average child from a professional family receives 560,000 more instances of encouraging feedback than discouraging feedback; a working- class child receives merely 100,000 more encouragements than discouragements; a welfare child receives 125,000 more discouragements than encouragements.

More on Hostess

There is a rumor that Mark is preparing a nice post on the whole Hostess bankruptcy story. So, to continue to generate context, consider this story from an actual employee:

Maybe the company was in an impossible situation. That is definitely one interpretation of the situation but the narrative is odd for this outcome. The argument that unions were to blame is hardly the case unless this account (above) is wracked with falsehoods. If the situation was hopeless then why did the high paid executives not call it over before raiding the pension? Was it because a longer tenure of salaries and job experience would be of personal benefit to them and they were no liable for the consequences of their decisions?

There are no easy answers, but a simple narrative of union greed or dysfunctional bargaining is clearly omitting lots of nuance. If nothing else, reneging on the repayment of the pension fund borrowing was hardly the ideal prelude to asking the union to trust future management promises.

In 2005 it was another contract year and this time there was no way out of concessions. The Union negotiated a deal that would save the company $150 million a year in labor. It was a tough internal battle to get people to vote for it. We turned it down twice. Finally the Union told us it was in our best interest and something had to give. So many of us, including myself, changed our votes and took the offer. Remember that next time you see CEO Rayburn on tv stating that we haven't sacrificed for this company. The company then emerged from bankruptcy. In 2005 before concessions I made $48,000, last year I made $34,000. My pay changed dramatically but at least I was still contributing to my self-funded pension.

In July of 2011 we received a letter from the company. It said that the $3+ per hour that we as a Union contribute to the pension was going to be 'borrowed' by the company until they could be profitable again. Then they would pay it all back. The Union was notified of this the same time and method as the individual members. No contact from the company to the Union on a national level.

This money will never be paid back. The company filed for bankruptcy and the judge ruled that the $3+ per hour was a debt the company couldn't repay. The Union continued to work despite this theft of our self-funded pension contributions for over a year. I consider this money stolen. No other word in the English language describes what they have done to this money.This illustrates a couple of things. One is that defined contribution pensions (i.e. the 401(k) and other such vehicles) are not necessarily a safe harbor from corporate games if something like this can happen without the union proactively agreeing. Two, the concessions made by the unions were pretty significant. They took pretty large pay cuts (29%) and lost additional money from the pension fund. No manager who made the decision to borrow this money was held liable.

Maybe the company was in an impossible situation. That is definitely one interpretation of the situation but the narrative is odd for this outcome. The argument that unions were to blame is hardly the case unless this account (above) is wracked with falsehoods. If the situation was hopeless then why did the high paid executives not call it over before raiding the pension? Was it because a longer tenure of salaries and job experience would be of personal benefit to them and they were no liable for the consequences of their decisions?

There are no easy answers, but a simple narrative of union greed or dysfunctional bargaining is clearly omitting lots of nuance. If nothing else, reneging on the repayment of the pension fund borrowing was hardly the ideal prelude to asking the union to trust future management promises.

Monday, November 19, 2012

Hoisted from the comments

A rather nice point from commenter Bill Trudo that I thought was worth emphasizing:

The problems at Hostess have been decades in the making. The company went into bankruptcy in 2004 and left in 2009 with numerous labor concessions, but without major reform to the pension system. Some people liked to blame that on the unions, but it is up to management to decide what is profitable or unprofitable. Now three years later, management has deemed their old agreements aren't profitable and that would be correct given how much money Hostess has been bleeding. And people still wonder why some union leaders were skeptical of management.

Skepticism is warranted, especially in light of Hostess having left bankruptcy in 2009 with more debt than it had in 2004 with falling sales. 2011 sales were down 28% from 2004. Of course, this is the union's fault that sales have dropped and not a failure of the company's leadership.

On top of that, management comes to the labor unions demanding 8% pay cuts and slashes to the pension, while the top executives increase their own pay--what a nice goodwill gesture. Some unsecured creditors actually filed suit over the pay raises.

Yes, pensions and work issues needed to be addressed. The unions had to make concessions, but it's difficult in light of what has happened for anyone to have any faith in what management has been doing at Hostess.

Now, enter two hedge funds, who hold the majority of secured debt, and they're likely looking to get out. After all, the business model isn't working; it's time for a showdown.

The Teamsters actually finally agreed to the wage and benefit concessions. Some of the other unions, including the Bakers' Union, didn't. Of course, I have a suspicion that some of the unions were acting in the best interest of all their union workers and not the union workers who were working at Hostess. Though, I also have suspicions that even if the unions capitulated to the hedge fund demands (they're the ones driving the show), Hostess would have likely been sold or have been back in bankruptcy in a few years.

This really gets to the core of the union/management dilemma -- it is hard to take things on faith. I remember many of my co-workers (including myself) putting in huge amounts of work for promises that never materialized. The classic "if you take a hit now we will remember you once this bad period is over". Curiously, it almost never works that way.

I also note that the narrative is "bad union wouldn't accept huge cuts" and not incompetent management was unable to make a top brand into a successful business. This is especially true of pension cuts. Underfunded pensions happen for a lot of reasons but they are usually much more of a management decision than a union decision. Maybe it was a bad decision for management to agree to the pension plan in the first place -- that is certainly possible. But it is always concerning to see no ethical qualms about removing obligations to workers (breaking agreements for work already done) while increasing your own wages.

What's with the (non)weird name?

Hi,

The regulars may have noticed something different about the top of the page. Observational Epidemiology is now West Coast Stat Views. This doesn't represent a change in content, rather a nod to truth in advertising. When this blog started, about two thousand posts ago, the name was both accurate and descriptive, but it soon morphed into a general statistics blog with a focus on topics that interested both of us and which connected (at least indirectly) with some relevant experience of one or both of us.

Both Joseph and I started out as corporate statisticians, so not surprisingly we're both mildly obsessed with business and economics. We both spent a great deal of time in academia so we're interested in education. As you'd expect from a blog originally called Observational Epidemiology, health care remains a big issue. As for politics and journalism, everybody needs a hobby.

Besides, I was getting tired of explaining what observational epidemiology meant.

Happy Holidays,

Mark

The regulars may have noticed something different about the top of the page. Observational Epidemiology is now West Coast Stat Views. This doesn't represent a change in content, rather a nod to truth in advertising. When this blog started, about two thousand posts ago, the name was both accurate and descriptive, but it soon morphed into a general statistics blog with a focus on topics that interested both of us and which connected (at least indirectly) with some relevant experience of one or both of us.

Both Joseph and I started out as corporate statisticians, so not surprisingly we're both mildly obsessed with business and economics. We both spent a great deal of time in academia so we're interested in education. As you'd expect from a blog originally called Observational Epidemiology, health care remains a big issue. As for politics and journalism, everybody needs a hobby.

Besides, I was getting tired of explaining what observational epidemiology meant.

Happy Holidays,

Mark

Sunday, November 18, 2012

"Peggy" "Noonan's" Life on Mars

Apparently Martians are also using the analytic and marketing methods we've been using since the late 20th Century.

From the Wall Street Journal (via DeLong via Kos)

The temptation is to start letting them slide, but there's an issue here of reputation and metadata. Noonan is recognized as a authority on politics and her reputation is backed by the reputations of the major news outlets that publish her writing and put her in front of the camera. All of this contributes to the metadata that tells us how much weight to give Noonan's statements.

For the system to work, information sources that are consistently unreliable have to take a reputational hit, but Noonan either knows nothing about how politics works today (which is, remember, her area of expertise) or, worse yet, she has such a low opinion of her readers' intelligence that she believes she can scare them by dropping a few technical terms.

If Noonan's reputation doesn't take the hit here then the reputations of those who publish and broadcast her will. Every time the Wall Street Journal prints one of these columns, the trust we can place in the paper diminishes just a little bit. It's a small effect but it's cumulative. Give it long enough and it can eat away the standing of even the Journal.

From the Wall Street Journal (via DeLong via Kos)

The other day a Republican political veteran forwarded me a hiring notice from the Obama 2012 campaign. It read like politics as done by Martians. The "Analytics Department" is looking for "predictive Modeling/Data Mining" specialists to join the campaign's "multi-disciplinary team of statisticians," which will use "predictive modeling" to anticipate the behavior of the electorate.It might seem that, after the last thousand or so Noonan columns, pointing out flaws in the latest entry is coals-to-Newcastle. This is, after all, the pundit who told us the day before the election that Romney was on track to win because "all the vibrations are right." (She said a lot of other memorable things in that column. You really ought to check it out.)

The temptation is to start letting them slide, but there's an issue here of reputation and metadata. Noonan is recognized as a authority on politics and her reputation is backed by the reputations of the major news outlets that publish her writing and put her in front of the camera. All of this contributes to the metadata that tells us how much weight to give Noonan's statements.

For the system to work, information sources that are consistently unreliable have to take a reputational hit, but Noonan either knows nothing about how politics works today (which is, remember, her area of expertise) or, worse yet, she has such a low opinion of her readers' intelligence that she believes she can scare them by dropping a few technical terms.

If Noonan's reputation doesn't take the hit here then the reputations of those who publish and broadcast her will. Every time the Wall Street Journal prints one of these columns, the trust we can place in the paper diminishes just a little bit. It's a small effect but it's cumulative. Give it long enough and it can eat away the standing of even the Journal.

Saturday, November 17, 2012

Go read Noah Smith

Today's post is really good:

Once again I notice that Canada has very tough drug patent protections (which might do a lot to improve innovation in the drug arena) and still manages to have much lower costs for medical care (as a percentage of GDP). Canadian Healthcare has some major downsides and I would never endorse it as the best possible system (I actually prefer the British NHS for a lot of reasons, that I really need to blog about).

Sicko is about America's health care system, and the alternatives. Before I saw Sicko, I believed the common line that, for all its flaws, America's health care system was "the best in the world". After I saw the movie, I did not believe anything of the kind. Sicko opened my eyes to the existence of Britain's National Health Service; after watching the movie, I looked into the NHS, and found that it achieves better results than the U.S. on almost any outcome measure, for far fewer costs. Importantly, it does this using a rational incentive system - doctors are paid for improving the health of their patients, not for recommending large numbers of expensive services.This really highlights the central dilemma facing US medical care. It is really expensive and it has very mediocre outcomes at a population level. It is possible that some people get exceptional medical care beyond that available elsewhere. And it is true that putting a lot of resources into a sector does tend to drive advances in that sector. My own person question is whether this is the best way to drive medical innovation; could targeted research money do more good on innovation than paying more for physician office visits?

I'm not sure, but around the same time that I stopped believing that America had the best health system in the world, I noticed that other people stopped saying it (and in fact started saying the opposite!). Around the same time I started thinking that Britain's NHS is the best alternative, I noticed a lot of policy-wonkish people praising that system in the press. Around the same time I started realizing the insanity of the "fee for service" incentive system, everyone started talking about it. So I wonder if Sicko, rather than just changing my mind, actually changed the whole national conversation

Once again I notice that Canada has very tough drug patent protections (which might do a lot to improve innovation in the drug arena) and still manages to have much lower costs for medical care (as a percentage of GDP). Canadian Healthcare has some major downsides and I would never endorse it as the best possible system (I actually prefer the British NHS for a lot of reasons, that I really need to blog about).

Jon Stewart opens up a big ol' can of historical context on Bill O'Reilly

An absolutely beautiful piece of satiric commentary.

Follow-up to yesterday's post

The discovery that Hostess tripled CEO pay (and boosted the pay of other senior executives) while blaming overpaid unions for the end of the company is a great example for yesterday's point. It would be fine to blame everyone involved. But some of the issues, like under-funded pension obligations, strike me as more of a management issue than a worker issue. But, regardless, it is striking that the narrative is all about the striking bakers and not the huge cash grab at the executive level.

EDIT: See Thoreau as well.

EDIT: See Thoreau as well.

Free Market Wages

I often get frustrated by defenses of extremely high pay as needed to be able to attract the incredibly small pool of high skill workers. This comment is pitch-perfect:

Why do we not have the same sort of bidding war for mid-level talent? I have the same question in a different way: why are managers getting high wages is seen as a sign of paying for talent but union workers are seen as using sleazy tactics to work the system? Do we see corporate boards setting salaries for CEOs as being fundamentally different than governments setting wages for government workers? In both cases a group of experts are setting wages based on expert opinion and not on free market principles.

The claim that high pay is necessary to attract and motivate good workers is not merely an economic postulate. If it were, it could apply across the wage distribution. Instead, it functions as a defence of inequality - used to justify higher pay for the rich, rather than for any job. For grunt workers, wages are a cost to be minimized regardless of consequence.This is a really good point; if wages for managers were treated like an expense for the company (instead of as an investment in talent) then would we have seen manger salaries rise so far in recent years?

Why do we not have the same sort of bidding war for mid-level talent? I have the same question in a different way: why are managers getting high wages is seen as a sign of paying for talent but union workers are seen as using sleazy tactics to work the system? Do we see corporate boards setting salaries for CEOs as being fundamentally different than governments setting wages for government workers? In both cases a group of experts are setting wages based on expert opinion and not on free market principles.

Friday, November 16, 2012

Today's tuition discussion

From Counterparties:

There was a period where this blog used to use the word "Canada" a lot. The reason is that Canada has a lot of interesting existence proofs for US policy. They have universal health care, acceptable health outcomes, and a much lower percentage of GDP spent on health care. Their system has flaws and trade-offs, but it shows that a diverse, multi-ethnic and geographically large country could control health care costs.

In the same sense they seem to have much lower tuition and very high quality Universities. They may not be the absolute best, but they are surprisingly competetive for a small country. I am not sure we'd want to adopt all of the problems of Canadian education, but it is worth noting that they seem to be able to deliver high quality education at a much lower price point. And this should have alerted the clever reader to the problem of Ms McArdle's argument -- why doesn't it happen in other countries, which also have a high return to education?

Megan McArdle argues that surging costs are as much a consequence as they are a cause of unprecedented levels of student debt, spurred on by government subsidies. But Mike Konczal flags a Department of Education study that shows that the government earns $1.14 back for every dollar it loans to students and asks, “What’s a good word for the opposite of a subsidy? Whatever it is, student loans are that”.This really seems to be a major problem with the modern discourse on education. We are all convinced that there has to be some sort of amazing (clever, counter-intuitive) theory about why tuition is going up. Bad policy, on the other hand, seems to be completely ignored. But if the government is making a net profit off of student loans, that seems to be rather concerning. Not because I object to profit, but because the loans are so high.

There was a period where this blog used to use the word "Canada" a lot. The reason is that Canada has a lot of interesting existence proofs for US policy. They have universal health care, acceptable health outcomes, and a much lower percentage of GDP spent on health care. Their system has flaws and trade-offs, but it shows that a diverse, multi-ethnic and geographically large country could control health care costs.

In the same sense they seem to have much lower tuition and very high quality Universities. They may not be the absolute best, but they are surprisingly competetive for a small country. I am not sure we'd want to adopt all of the problems of Canadian education, but it is worth noting that they seem to be able to deliver high quality education at a much lower price point. And this should have alerted the clever reader to the problem of Ms McArdle's argument -- why doesn't it happen in other countries, which also have a high return to education?

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Social Security: really, what is going on here?

I keep asking the same question as the commenter on The Incidental Economist asks:

Social security is a popular benefit and something like 80-90% of the population will eventually have it as an important piece of their income. Just what is going on here?

In fact, Social Security is NOT in crisis. If we hiked payroll taxes by two percentage points we would probably take care of the payroll tax deficit. Yes, that’s a regressive tax and we should be cautious about doing it. But our long-run budget problems are mostly in health care. Why the unearthly fascination with cutting Social Security?I mean, seriously, why is it such conventional wisdom that it needs to be reformed? It is true that a private alternative would be a great revenue center for finance types. But a lot of things would be great revenue sources that we don't privatize for good reason (Police, Military), either because it would be inefficient or because only the government can guarentee long term contracts like those required for retirement in 45 years.

Social security is a popular benefit and something like 80-90% of the population will eventually have it as an important piece of their income. Just what is going on here?

Sunday, November 11, 2012

The biggest political story you probably haven't heard

(At least if you're not on Pacific Time) were California propositions 30, 32, and 36. I don't have time to give this the write-up it deserves, but the LA Times voting guide is a good starting point. The short version is this: under long odds (including the worst piece of vanity politics since Nader hung it up and a special cameo appearance from the Koch brothers) and by significant margins, the largest state in the union has just made a sharp turn to the left on taxes, education, unions and mass incarceration.

What's more, I suspect that the interest in these issues may have pumped up voter turn out and, as a result, helped Obama's popular vote totals. Add to that a potential supermajority in both houses.

None of this may be as interesting as genetically modified food and condoms for porn stars but it's a damned sight more important.

What's more, I suspect that the interest in these issues may have pumped up voter turn out and, as a result, helped Obama's popular vote totals. Add to that a potential supermajority in both houses.

None of this may be as interesting as genetically modified food and condoms for porn stars but it's a damned sight more important.

Saturday, November 10, 2012

You really should be reading Andrew Gelman's blog

I considered this point (made by Andrew Gelman) to be really interesting:

All statisticians use prior information in their statistical analysis. Non-Bayesians express their prior information not through a probability distribution on parameters but rather through their choice of methods. I think this non-Bayesian attitude is too restrictive, but in this case a small amount of reflection would reveal the inappropriateness of this procedure for this example.I had never phrased things like this but it does seem to be a sensible description of what I (essentially a Frequentist) actually do in real life. This may be a very good teaching point and it nicely illustrates that all analysis involves priors -- just that some are more explicit than others.

More for blogger's to-do list

Really swamped this week, which invariably means that all sorts of interesting topics have been popping up. Here's a partial list. I'll try to get to as many as I can, but if any fellow bloggers want to beat me to the punch please go for it.

1. The ethics (and advisability) of psychoanalyzing your opponents

(when is it acceptable, wise and not overly sleazy to try to explain your opponents' actions using psychology and sociology and how do you avoid using those explanations to dismiss valid arguments on the other side)

Link to Pauline Kael's "Raising Kane" (no, really)

2. Implications of a submerging Republican majority

A. Scarcity and cognitive dissonance -- link to Cialdini

B. The looting phase (or Karl Rove is not your friend) -- link to Red State, Rick Perlstein, David Frum

C. Waiting for the Big Dog -- link to Ed Kilgore (at some length)

D. Nate Silver and the Sandy Hypothesis -- link to Talking Points and 538

3. The killer app for the driverless car -- it's not what you think

4. Daniel Engber doesn't seem to get the subtleties of statistics debates -- link to this and this

5. Nudge cars (I'll explain later)

6. Homemade Pi -- a classroom exercise for geometry, spreadsheets and Monte Carlo techniques

7. More Groupon -- link to Felix Salmon

8. Trivial thoughts -- athletic actors

9. The annual Toys-for-Tots post

1. The ethics (and advisability) of psychoanalyzing your opponents

(when is it acceptable, wise and not overly sleazy to try to explain your opponents' actions using psychology and sociology and how do you avoid using those explanations to dismiss valid arguments on the other side)

Link to Pauline Kael's "Raising Kane" (no, really)

2. Implications of a submerging Republican majority

A. Scarcity and cognitive dissonance -- link to Cialdini

B. The looting phase (or Karl Rove is not your friend) -- link to Red State, Rick Perlstein, David Frum

C. Waiting for the Big Dog -- link to Ed Kilgore (at some length)

D. Nate Silver and the Sandy Hypothesis -- link to Talking Points and 538

3. The killer app for the driverless car -- it's not what you think

4. Daniel Engber doesn't seem to get the subtleties of statistics debates -- link to this and this

5. Nudge cars (I'll explain later)

6. Homemade Pi -- a classroom exercise for geometry, spreadsheets and Monte Carlo techniques

7. More Groupon -- link to Felix Salmon

8. Trivial thoughts -- athletic actors

9. The annual Toys-for-Tots post

Thursday, November 8, 2012

Podhoretz mans up

Lots of pundits did shoddy work covering the past election. Very few have actually owned up to it.

From NPR:

p.s. Add Unskewed Polls' Dean Chambers to this list.:

From NPR:

FOLKENFLIK: But if Florida stays blue, Silver will have picked every state correctly, along with the president's margin of victory. Conservative columnist John Podhoretz of the New York Post and Commentary magazine had earlier argued pollsters were getting it wrong by ignoring the high turnout by Republicans in the 2010 elections that swept the GOP into control of the U.S. House. The 2012 race would be the same, Podhoretz argued, quite mistakenly, as it turned out.

JOHN PODHORETZ: That view was strengthened and amplified by what I wanted to happen, which I freely confess. People don't ordinarily cast a skeptical eye on data and information that supports their opinions. They're happy to take it.

p.s. Add Unskewed Polls' Dean Chambers to this list.:

“Most of the polls I ‘unskewed’ were based on samples that generally included about five or six or seven percent more Democrats than Republicans, and I doubted and questioned the results of those polls, and then ‘unskewed’ them based on my belief that a nearly equal percentage of Democrats and Republicans would turn out in the actual election this year,” Chambers wrote on The Examiner website. “I was wrong on that assumption and those who predicted a turnout model of five or six percent in favor of Democrats were right. Likewise, the polling numbers they produced going on that assumption turned out to be right and my ‘unskewed’ numbers were off the mark.”

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

That certainly was a close one

Neck and neck

A dead heat

Too close to call

Virtually tied

Plan on a long night

One of the things I hope people will take away from the election is a reminder of how bad journalistic group think has become. Narratives are converged upon instantly. treated as axioms no matter how many non-journalists reach a different conclusion, and defended with an appalling level of nastiness (just ask Nate Silver).

What's even more depressing is the realization that these pundits will pay no penalty for being willfully, arrogantly, childishly wrong.

A dead heat

Too close to call

Virtually tied

Plan on a long night

One of the things I hope people will take away from the election is a reminder of how bad journalistic group think has become. Narratives are converged upon instantly. treated as axioms no matter how many non-journalists reach a different conclusion, and defended with an appalling level of nastiness (just ask Nate Silver).

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

What's even more depressing is the realization that these pundits will pay no penalty for being willfully, arrogantly, childishly wrong.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

When it comes to the horse race, what do the people say?

It's possible to find exceptions but the general consensus among political scientists, poll aggregators and betting markets has generally been that Obama held a small but respectable lead. Journalists, on the other hand, seem to be contractually required to describe the race with some synonym for tied (only breaking the pattern occasionally to talk about Romney's momentum).

With that in mind, this quote from Andrew Kohut of Pew is particularly interesting...

With that in mind, this quote from Andrew Kohut of Pew is particularly interesting...

RAZ: The popular vote. Yeah. Interestingly, when you asked voters who they think will win, 52 percent say Obama, just 32 percent say Romney.

KOHUT: Yes. That has been pretty consistent through this election. Obama is seen by average voters as the likely winner of the next election. That's another measure that's been a pretty good indicator of who will win the election. That is the candidate that the electorate thinks will win generally does win.

Life on 49-49

[Following up on this post, here are some more (barely) pre-election thoughts on how polls gang aft agley. I believe Jonathan Chait made some similar points. Some of Nate Silver's critics also wandered into some neighboring territory (with the important distinction that Chait understood the underlying concepts)]

Assume that there's an alternate world called Earth 49-49. This world is identical to ours in all but one respect: for almost all of the presidential campaign, 49% of the voters support Obama and 49% support Romney. There has been virtually no shift in who plans to vote for whom.

Despite this, all of the people on 49-49 believe that they're on our world, where large segments of the voters are shifting their support from Romney to Obama then from Obama to Romney. They weren't misled to this belief through fraud -- all of the polls were administered fairly and answered honestly -- nor was it a case of stupidity or bad analysis -- the political scientists on 49-49 are highly intelligent and conscientious -- rather it had to do with the nature of polling.

Pollsters had long tracked campaigns by calling random samples of potential voters. As campaign became more drawn out and journalistic focus shifted to the horse race aspects of election, these phone polls proliferated. At the same time, though, the response rates dropped sharply, going from more than one in three to less than one in ten.

A big drop in response rates always raises questions about selection bias since the change may not affect all segments of the population proportionally (more on that -- and this report -- later). It also increases the potential magnitude of these effects.

Consider these three scenarios. What would happen if you could do the following (in the first two cases, assume no polling bias):

A. Convince one percent of undecideds to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent stays at 49 -- one percent poll advantage

B. Convince one percent of opponent's supporters to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent drops to 48 -- two percent poll advantage

C. Convince an additional one percent of your supporters to answer the phone when a pollster calls. You go to over 51% while your opponent drops to under 47%-- around a five percent poll advantage.

Of course, no one was secretly plotting to game the polls, but poll responses are basically just people agreeing to talk to you about politics, and lots of things can affect people's willingness to talk about their candidate, including things that would almost never affect their actual votes (at least not directly but more on that later).

In 49-49, the Romney campaign hit a stretch of embarrassing news coverage while Obama was having, in general, a very good run. With a couple of exceptions, the stories were trivial, certainly not the sort of thing that would cause someone to jump the substantial ideological divide between the two candidates so, none of Romney's supporters shifted to Obama or to undecided. Many did, however, feel less and less like talking to pollsters. So Romney's numbers started to go down which only made his supporters more depressed and reluctant to talk about their choice.

This reluctance was already just starting to fade when the first debate came along. As Josh Marshall has explained eloquently and at great length since early in the primaries, the idea of Obama, faced with a strong attack and deprived of his teleprompter, collapsing in a debate was tremendously important and resonant to the GOP base. That belief was a major driver of the support for Gingrich, despite all his baggage; no one ever accused Newt of being reluctant to go for the throat.

It's not surprising that, after weeks of bad news and declining polls, the effect on the Republican base of getting what looked very much like the debate they'd hoped for was cathartic. Romney supporters who had been avoiding pollsters suddenly couldn't wait to take the calls. By the same token. Obama supporters who got their news from Ed Schultz and Chris Matthews really didn't want to talk right now.

The polls shifted in Romney's favor even though, had the election been held the week after the debate, the result would have been the same as it would have been had the election been held two weeks before -- 49% to 49%. All of the changes in the polls had come from core voters on both sides. The voters who might have been persuaded weren't that interested in the emotional aspect of the conventions and the debates and were already familiar with the substantive issues both events raised.

So response bias was amplified by these factors:

1. the effect was positively correlated with the intensity of support

2. it was accompanied by matching but opposite effects on the other side

3. there were feedback loops -- supporters of candidates moving up in the polls were happier and more likely to respond while supporters of candidates moving down had the opposite reaction.

You might wonder how the pollsters and political scientists of this world missed this. The answer that they didn't. They were concerned about selection effects and falling response rates, but the problems with the data were difficult to catch definitively thanks to some serious obscuring factors:

1. Researchers have to base their conclusions off of the historical record when the effect was not nearly so big.

2. Things are correlated in a way that's difficult to untangle. The things you would expect to make supporters less enthusiastic about talking about their candidate are often the same things you'd expect to lower support for that candidate

3. As mentioned before, there are compensatory effects. Since response rates for the two parties are inversely related, the aggregate is fairly stable.

4. The effect of embarrassment and elation tend to fade over time so that most are gone by the actual election.

5. There's a tendency to converge as the election approaches. Mainly because likely voter screens become more accurate.

6. Poll predictions can be partially self-fulfilling. If the polls indicate a sufficiently low chance of winning, supporters can become discouraged, allies can desert you and money can dry up. The result is, again, convergence.

For the record, I don't think we live on 49-49. I do, however, think that at least some of the variability we've seen in the polls can be traced back to selection effects similar to those described here and I have to believe it's likely to get worse.

Assume that there's an alternate world called Earth 49-49. This world is identical to ours in all but one respect: for almost all of the presidential campaign, 49% of the voters support Obama and 49% support Romney. There has been virtually no shift in who plans to vote for whom.

Despite this, all of the people on 49-49 believe that they're on our world, where large segments of the voters are shifting their support from Romney to Obama then from Obama to Romney. They weren't misled to this belief through fraud -- all of the polls were administered fairly and answered honestly -- nor was it a case of stupidity or bad analysis -- the political scientists on 49-49 are highly intelligent and conscientious -- rather it had to do with the nature of polling.

Pollsters had long tracked campaigns by calling random samples of potential voters. As campaign became more drawn out and journalistic focus shifted to the horse race aspects of election, these phone polls proliferated. At the same time, though, the response rates dropped sharply, going from more than one in three to less than one in ten.

A big drop in response rates always raises questions about selection bias since the change may not affect all segments of the population proportionally (more on that -- and this report -- later). It also increases the potential magnitude of these effects.

Consider these three scenarios. What would happen if you could do the following (in the first two cases, assume no polling bias):

A. Convince one percent of undecideds to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent stays at 49 -- one percent poll advantage

B. Convince one percent of opponent's supporters to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent drops to 48 -- two percent poll advantage

C. Convince an additional one percent of your supporters to answer the phone when a pollster calls. You go to over 51% while your opponent drops to under 47%-- around a five percent poll advantage.

Of course, no one was secretly plotting to game the polls, but poll responses are basically just people agreeing to talk to you about politics, and lots of things can affect people's willingness to talk about their candidate, including things that would almost never affect their actual votes (at least not directly but more on that later).

In 49-49, the Romney campaign hit a stretch of embarrassing news coverage while Obama was having, in general, a very good run. With a couple of exceptions, the stories were trivial, certainly not the sort of thing that would cause someone to jump the substantial ideological divide between the two candidates so, none of Romney's supporters shifted to Obama or to undecided. Many did, however, feel less and less like talking to pollsters. So Romney's numbers started to go down which only made his supporters more depressed and reluctant to talk about their choice.

This reluctance was already just starting to fade when the first debate came along. As Josh Marshall has explained eloquently and at great length since early in the primaries, the idea of Obama, faced with a strong attack and deprived of his teleprompter, collapsing in a debate was tremendously important and resonant to the GOP base. That belief was a major driver of the support for Gingrich, despite all his baggage; no one ever accused Newt of being reluctant to go for the throat.

It's not surprising that, after weeks of bad news and declining polls, the effect on the Republican base of getting what looked very much like the debate they'd hoped for was cathartic. Romney supporters who had been avoiding pollsters suddenly couldn't wait to take the calls. By the same token. Obama supporters who got their news from Ed Schultz and Chris Matthews really didn't want to talk right now.

The polls shifted in Romney's favor even though, had the election been held the week after the debate, the result would have been the same as it would have been had the election been held two weeks before -- 49% to 49%. All of the changes in the polls had come from core voters on both sides. The voters who might have been persuaded weren't that interested in the emotional aspect of the conventions and the debates and were already familiar with the substantive issues both events raised.

So response bias was amplified by these factors:

1. the effect was positively correlated with the intensity of support

2. it was accompanied by matching but opposite effects on the other side

3. there were feedback loops -- supporters of candidates moving up in the polls were happier and more likely to respond while supporters of candidates moving down had the opposite reaction.

You might wonder how the pollsters and political scientists of this world missed this. The answer that they didn't. They were concerned about selection effects and falling response rates, but the problems with the data were difficult to catch definitively thanks to some serious obscuring factors:

1. Researchers have to base their conclusions off of the historical record when the effect was not nearly so big.

2. Things are correlated in a way that's difficult to untangle. The things you would expect to make supporters less enthusiastic about talking about their candidate are often the same things you'd expect to lower support for that candidate

3. As mentioned before, there are compensatory effects. Since response rates for the two parties are inversely related, the aggregate is fairly stable.

4. The effect of embarrassment and elation tend to fade over time so that most are gone by the actual election.

5. There's a tendency to converge as the election approaches. Mainly because likely voter screens become more accurate.

6. Poll predictions can be partially self-fulfilling. If the polls indicate a sufficiently low chance of winning, supporters can become discouraged, allies can desert you and money can dry up. The result is, again, convergence.

For the record, I don't think we live on 49-49. I do, however, think that at least some of the variability we've seen in the polls can be traced back to selection effects similar to those described here and I have to believe it's likely to get worse.

Monday, November 5, 2012

Elasticity, Plasticity and Creep in polls

I've been thinking quite a bit about polls lately, about what can go wrong with them, and how they might react and even how some of Nate Silver's critics have almost stumbled onto a couple of valid points (albeit ones that Silver has acknowledged).

I'm working on a full post on the subject but in the meantime, here's some background complete with sound track. (hit play now)

One of the things I've been coming up against is what can happen when something moves a poll.

1. Elasticity

Let's say a candidate gives a rousing speech that gets base fired up. It makes supporters more likely to talk to pollsters but it doesn't really change anyone's mind. After a short period the excitement fades and the polls return to their previous position.

2. Plasticity

Another speech, but this this time with enough substance to win over some undecideds. The polls move to another position and stay there.

3. Creep

This starts with an event that would normally cause an elastic shift, but the deformation of the polls is drawn out, either because it's followed by other trivial events or because the timing of the polls makes it seem drawn out or because the media simply decides to dwell on it or (most likely) some combination. Under these circumstances we can easily get a feedback loop where bad polls create the impression of eroding support which causes supporters to become discouraged and money to dry up which causes support to actually erode.

I suspect Romney was experiencing creep in the last week of September.

I'll try to flesh this out more in the next 24. In the meantime, does anyone have any thoughts on the subject?

I'm working on a full post on the subject but in the meantime, here's some background complete with sound track. (hit play now)

One of the things I've been coming up against is what can happen when something moves a poll.

1. Elasticity

Let's say a candidate gives a rousing speech that gets base fired up. It makes supporters more likely to talk to pollsters but it doesn't really change anyone's mind. After a short period the excitement fades and the polls return to their previous position.

2. Plasticity

Another speech, but this this time with enough substance to win over some undecideds. The polls move to another position and stay there.

3. Creep

This starts with an event that would normally cause an elastic shift, but the deformation of the polls is drawn out, either because it's followed by other trivial events or because the timing of the polls makes it seem drawn out or because the media simply decides to dwell on it or (most likely) some combination. Under these circumstances we can easily get a feedback loop where bad polls create the impression of eroding support which causes supporters to become discouraged and money to dry up which causes support to actually erode.

I suspect Romney was experiencing creep in the last week of September.

I'll try to flesh this out more in the next 24. In the meantime, does anyone have any thoughts on the subject?

Sunday, November 4, 2012

A very good perspective on the latest Star Wars news

Star Wars has been sold to Disney for 4.05 billion dollars. George Lucas's high risk decision to push through the difficult task of making the first Star Wars movie appears to have paid off. While some people are worried about the new owners of the property, I think this piece has a very good perspective on the whole transaction and is definitely worth reading.

When a stag/hare hunt is not a stag/hare hunt

This speculation from a TPM reader got me to thinking...

I don't want to get bunch of emails saying I don't know anything about game theory (which is true but hopefully not relevant here), so to be clear I'm not saying this is a stag hunt, just that this raises some similar tactical questions about diverting resources from a big but unlikely pay-off (the Electoral College) to smaller ones (the popular vote, better down-ticket results).

Regarding dumping money into non-competitive states, here in Dallas nearly every other commercial is an anti-Obama ad from the superPAC, “Restore our Future.” I’m trying to figure out why they’re dumping so much money into the Texas ad market when I’d assume Texas is about as solidly red as it gets. I have two theories:

1. It’s to build up GOP enthusiasm for down-ticket races.This reminded me of the Stag Hunt game where players have to decide whether to stick with a group in hopes of a big pay-off that's dependent on cooperation or go off on their own for a smaller but more likely pay-off.

2. They need to spend some of their donations on something other than lining their own pockets to help keep people from realizing they’re nothing but grifters who have been lining their own pockets with all that political donation money.

I don't want to get bunch of emails saying I don't know anything about game theory (which is true but hopefully not relevant here), so to be clear I'm not saying this is a stag hunt, just that this raises some similar tactical questions about diverting resources from a big but unlikely pay-off (the Electoral College) to smaller ones (the popular vote, better down-ticket results).

Strauss and the war on data

The most important aspect of Randianism as currently practiced is the lies its adherents tell themselves. "When you're successful, it's because other people are inferior to you." "When you fail, it's because inferior people persecute you (call it going Roark)." "One of these days you're going to run away and everyone who's been mean to you will be sorry."

The most important aspect of Straussianism as currently practiced is the lies its adherents tell others. Having started from the assumption that traditional democracy can't work because most people aren't smart enough to handle the role of voter, the Straussians conclude that superior minds must, for the good of society, lie to and manipulate the masses.

Joseph and I have an ongoing argument about which school is worse, a question greatly complicated by the compatibility of the two systems and the overlap of believers and their tactics and objectives. Joseph generally argues that Rand is worse (without, of course, defending Strauss) while I generally take the opposite position.

This week brought news that I think bolsters my case (though I suspect Joseph could easily turn it around to support his): one of the logical consequences of assuming typical voters can't evaluate information on their own is that data sources that are recognized as reliable are a threat to society. They can't be spun and they encourage people to make their own decisions.

To coin a phrase, if the masses can't handle the truth and need instead to be fed a version crafted by the elite to keep the people happy and doing what's best for them, the public's access to accurate, objective information has to be tightly controlled. With that in mind, consider the following from Jared Bernstein:

Going back a few months, we had this from Businessweek:

The most important aspect of Straussianism as currently practiced is the lies its adherents tell others. Having started from the assumption that traditional democracy can't work because most people aren't smart enough to handle the role of voter, the Straussians conclude that superior minds must, for the good of society, lie to and manipulate the masses.

Joseph and I have an ongoing argument about which school is worse, a question greatly complicated by the compatibility of the two systems and the overlap of believers and their tactics and objectives. Joseph generally argues that Rand is worse (without, of course, defending Strauss) while I generally take the opposite position.

This week brought news that I think bolsters my case (though I suspect Joseph could easily turn it around to support his): one of the logical consequences of assuming typical voters can't evaluate information on their own is that data sources that are recognized as reliable are a threat to society. They can't be spun and they encourage people to make their own decisions.

To coin a phrase, if the masses can't handle the truth and need instead to be fed a version crafted by the elite to keep the people happy and doing what's best for them, the public's access to accurate, objective information has to be tightly controlled. With that in mind, consider the following from Jared Bernstein:

[D]ue to pressure from Republicans, the Congressional Research Service is withdrawing a report that showed the lack of correlation between high end tax cuts and economic growth.And with Sandy still on everyone's mind, here's something from Menzie Chinn:

The study, by economist Tom Hungerford, is of high quality, and is one I’ve cited here at OTE. Its findings are fairly common in the economics literature and the concerns raised by that noted econometrician Mitch McConnell are trumped up and bogus. He and his colleagues don’t like the findings because they strike at the supply-side arguments that they hold so dear.

NOAA's programs are in function 300, Natural Resources and Environment, along with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and a range of conservation and natural resources programs. In the near term, function 300 would be 14.6 percent lower in 2014 in the Ryan budget according to the Washington Post. It quotes David Kendall of The Third Way as warning about the potential impact on weather forecasting: "'Our weather forecasts would be only half as accurate for four to eight years until another polar satellite is launched,' estimates Kendall. 'For many people planning a weekend outdoors, they may have to wait until Thursday for a forecast as accurate as one they now get on Monday. … Perhaps most affected would be hurricane response. Governors and mayors would have to order evacuations for areas twice as large or wait twice as long for an accurate forecast.'"There are also attempts from prominent conservatives to delegitimize objective data:

Apparently, Jack Welch, former chairman and CEO of General Electric, is accusing the Bureau of Labor Statistics of manipulating the jobs report to help President Obama. Others seem to be adding their voices to this slanderous lie. It is simply outrageous to make such a claim and echoes the worrying general distrust of facts that seems to have swept segments of our nation. The BLS employment report draws on two surveys, one (the establishment survey) of 141,000 businesses and government agencies and the other (the household survey) of 60,000 households. The household survey is done by the Census Bureau on behalf of BLS. It’s important to note that large single-month divergences between the employment numbers in these two surveys (like the divergence in September) are just not that rare. EPI’s Elise Gould has a great paper on the differences between these two surveys.We can also put many of the attacks against Nate Silver in this category.

BLS is a highly professional agency with dozens of people involved in the tabulation and analysis of these data. The idea that the data are manipulated is just completely implausible. Moreover, the data trends reported are clearly in line with previous monthly reports and other economic indicators (such as GDP). The key result was the 114,000 increase in payroll employment from the establishment survey, which was right in line with what forecasters were expecting. This was a positive growth in jobs but roughly the amount to absorb a growing labor force and maintain a stable, not falling, unemployment rate. If someone wanted to help the president, they should have doubled the job growth the report showed. The household survey was much more positive, showing unemployment falling from 8.1 percent to 7.8 percent. These numbers are more volatile month to month and it wouldn’t be surprising to see unemployment rise a bit next month. Nevertheless, there’s nothing implausible about the reported data. The household survey has shown greater job growth in the recovery than the establishment survey throughout the recovery. The labor force participation rate (the share of adults who are working or unemployed) increased to 63.6 percent, which is an improvement from the prior month but still below the 63.7 percent reported for July. All in all, there was nothing particularly strange about this month’s jobs reports—and certainly nothing to spur accusations of outright fraud.

Going back a few months, we had this from Businessweek:

The House Committee on Appropriations recently proposed cutting the Census budget to $878 million, $10 million below its current budget and $91 million less than the bureau’s request for the next fiscal year. Included in the committee number is a $20 million cut in funding for this year’s Economic Census, considered the foundation of U.S. economic statistics.And Bruce Bartlett had a whole set of examples involving Newt Gingrich:

On Nov. 21, Newt Gingrich, who is leading the race for the Republican presidential nomination in some polls, attacked the Congressional Budget Office. In a speech in New Hampshire, Mr. Gingrich said the C.B.O. "is a reactionary socialist institution which does not believe in economic growth, does not believe in innovation and does not believe in data that it has not internally generated."

Mr. Gingrich's charge is complete nonsense. The former C.B.O. director Douglas Holtz-Eakin, now a Republican policy adviser, labeled the description "ludicrous." Most policy analysts from both sides of the aisle would say the C.B.O. is one of the very few analytical institutions left in government that one can trust implicitly.

It's precisely its deep reservoir of respect that makes Mr. Gingrich hate the C.B.O., because it has long stood in the way of allowing Republicans to make up numbers to justify whatever they feel like doing.

...

Mr. Gingrich has long had special ire for the C.B.O. because it has consistently thrown cold water on his pet health schemes, from which he enriched himself after being forced out as speaker of the House in 1998. In 2005, he wrote an op-ed article in The Washington Times berating the C.B.O., then under the direction of Mr. Holtz-Eakin, saying it had improperly scored some Gingrich-backed proposals. At a debate on Nov. 5, Mr. Gingrich said, "If you are serious about real health reform, you must abolish the Congressional Budget Office because it lies."

...

Because Mr. Gingrich does know more than most politicians, the main obstacles to his grandiose schemes have always been Congress's professional staff members, many among the leading authorities anywhere in their areas of expertise.

To remove this obstacle, Mr. Gingrich did everything in his power to dismantle Congressional institutions that employed people with the knowledge, training and experience to know a harebrained idea when they saw it. When he became speaker in 1995, Mr. Gingrich moved quickly to slash the budgets and staff of the House committees, which employed thousands of professionals with long and deep institutional memories.

Of course, when party control in Congress changes, many of those employed by the previous majority party expect to lose their jobs. But the Democratic committee staff members that Mr. Gingrich fired in 1995 weren't replaced by Republicans. In essence, the positions were simply abolished, permanently crippling the committee system and depriving members of Congress of competent and informed advice on issues that they are responsible for overseeing.

Mr. Gingrich sold his committee-neutering as a money-saving measure. How could Congress cut the budgets of federal agencies if it wasn't willing to cut its own budget, he asked. In the heady days of the first Republican House since 1954, Mr. Gingrich pretty much got whatever he asked for.

In addition to decimating committee budgets, he also abolished two really useful Congressional agencies, the Office of Technology Assessment and the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. The former brought high-level scientific expertise to bear on legislative issues and the latter gave state and local governments an important voice in Congressional deliberations.

The amount of money involved was trivial even in terms of Congress's budget. Mr. Gingrich's real purpose was to centralize power in the speaker's office, which was staffed with young right-wing zealots who followed his orders without question. Lacking the staff resources to challenge Mr. Gingrich, the committees could offer no resistance and his agenda was simply rubber-stamped.

Unfortunately, Gingrichism lives on. Republican Congressional leaders continually criticize every Congressional agency that stands in their way. In addition to the C.B.O., one often hears attacks on the Congressional Research Service, the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Government Accountability Office.

Lately, the G.A.O. has been the prime target. Appropriators are cutting its budget by $42 million, forcing furloughs and cutbacks in investigations that identify billions of dollars in savings yearly. So misguided is this effort that Senator Tom Coburn, Republican of Oklahoma and one of the most conservative members of Congress, came to the agency's defense.

In a report issued by his office on Nov. 16, Senator Coburn pointed out that the G.A.O.'s budget has been cut by 13 percent in real terms since 1992 and its work force reduced by 40 percent -- more than 2,000 people. By contrast, Congress's budget has risen at twice the rate of inflation and nearly doubled to $2.3 billion from $1.2 billion over the last decade.

Mr. Coburn's report is replete with examples of budget savings recommended by G.A.O. He estimated that cutting its budget would add $3.3 billion a year to government waste, fraud, abuse and inefficiency that will go unidentified.

For good measure, Mr. Coburn included a chapter in his report on how Congressional committees have fallen down in their responsibility to exercise oversight. The number of hearings has fallen sharply in both the House and Senate. Since the beginning of the Gingrich era, they have fallen almost in half, with the biggest decline coming in the 104th Congress (1995-96), his first as speaker.

In short, Mr. Gingrich's unprovoked attack on the C.B.O. is part of a pattern. He disdains the expertise of anyone other than himself and is willing to undercut any institution that stands in his way. Unfortunately, we are still living with the consequences of his foolish actions as speaker.

We could really use the Office of Technology Assessment at a time when Congress desperately needs scientific expertise on a variety of issues in involving health, energy, climate change, homeland security and many others. And given the enormous stress suffered by state and local governments as they are forced by Washington to do more with less, an organization like the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations would be invaluable.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Epidemiological Measures

While the quote below seems political but I actually want to use it to make an epidemiological point rather than discussing politics:

For two people in the same position, there is a correlation between earnings and work (notice that I did not say a strong correlation). It is tempting to assume, based on this micro-ordering, that the macro ordering of income is also related to the amount of work done or value created. But it's obvious that this measure fails or else we would praise unions for working harder than regular workers rather than worrying that they were over-paid.

I think that this problem is a consequence of us (as a society) wanting to assume clean values to soft and complex constructs. We will all be better off if we resist this impulse.

The most important intellectual pathology to afflict conservatism during the Obama era is its embrace of Ayn Rand’s moral philosophy of capitalism. Rand considered the free market a perfect arbiter of a person’s worth; their market earnings reflect their contribution to society, and their right to keep those earnings was absolute. Politics, as she saw it, was essentially a struggle of the market’s virtuous winners to protect their wealth from confiscation by the hordes of inferiors who could outnumber them.One issue that I see over and over again is mistaking the measure for the outcome. So people will fixate on body mass index as a measure of adiposity. But doing so classifies Brad Pitt (famous for his muscles) as being either overweight or obese. It is tempting to use an easy to measure correlated variable in place of the actual measure.

For two people in the same position, there is a correlation between earnings and work (notice that I did not say a strong correlation). It is tempting to assume, based on this micro-ordering, that the macro ordering of income is also related to the amount of work done or value created. But it's obvious that this measure fails or else we would praise unions for working harder than regular workers rather than worrying that they were over-paid.

I think that this problem is a consequence of us (as a society) wanting to assume clean values to soft and complex constructs. We will all be better off if we resist this impulse.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Flexible hours

I was a big fan of flexible hours for staff, when positions needed work done on a non-critical time scale. But this new trend twards scheduling hours at the last minute and a new focus on part time work seems deeply sub-optimal. Even the case the article cites as wanting to have part time work:

But the other interesting piece is this: