Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, December 23, 2016

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Our annual Toys-for-Tots post

[Slightly modified from previous years.]

A good Christmas can do a lot to take the edge off of a bad year both for children and their parents (and a lot of families are having a bad year). It's the season to pick up a few toys, drop them by the fire station and make some people feel good about themselves during what can be one of the toughest times of the year.

If you're new to the Toys-for-Tots concept, here are the rules I normally use when shopping:

The gifts should be nice enough to sit alone under a tree. The child who gets nothing else should still feel that he or she had a special Christmas. A large stuffed animal, a big metal truck, a large can of Legos with enough pieces to keep up with an active imagination. You can get any of these for around twenty or thirty bucks at Target, Wal-Mart or Costco. Toys-R-Us had some good sales last year;

Shop smart. The better the deals the more toys can go in your cart;

No batteries. (I'm a strong believer in kid power);*

Speaking of kid power, it's impossible to be sedentary while playing with a basketball;

No toys that need lots of accessories;

For games, you're generally better off going with a classic;

No movie or TV show tie-ins. (This one's kind of a personal quirk and I will make some exceptions like Sesame Street);

Look for something durable. These will have to last;

For smaller children, you really can't beat Fisher Price and PlaySkool. Both companies have mastered the art of coming up with cleverly designed toys that children love and that will stand up to generations of energetic and creative play.

* I'd like to soften this position just bit. It's okay for a toy to use batteries, just not to need them. Fisher Price and PlaySkool have both gotten into the habit of adding lights and sounds to classic toys, but when the batteries die, the toys live on, still powered by the energy of children at play.

A good Christmas can do a lot to take the edge off of a bad year both for children and their parents (and a lot of families are having a bad year). It's the season to pick up a few toys, drop them by the fire station and make some people feel good about themselves during what can be one of the toughest times of the year.

If you're new to the Toys-for-Tots concept, here are the rules I normally use when shopping:

The gifts should be nice enough to sit alone under a tree. The child who gets nothing else should still feel that he or she had a special Christmas. A large stuffed animal, a big metal truck, a large can of Legos with enough pieces to keep up with an active imagination. You can get any of these for around twenty or thirty bucks at Target, Wal-Mart or Costco. Toys-R-Us had some good sales last year;

Shop smart. The better the deals the more toys can go in your cart;

No batteries. (I'm a strong believer in kid power);*

Speaking of kid power, it's impossible to be sedentary while playing with a basketball;

No toys that need lots of accessories;

For games, you're generally better off going with a classic;

No movie or TV show tie-ins. (This one's kind of a personal quirk and I will make some exceptions like Sesame Street);

Look for something durable. These will have to last;

For smaller children, you really can't beat Fisher Price and PlaySkool. Both companies have mastered the art of coming up with cleverly designed toys that children love and that will stand up to generations of energetic and creative play.

* I'd like to soften this position just bit. It's okay for a toy to use batteries, just not to need them. Fisher Price and PlaySkool have both gotten into the habit of adding lights and sounds to classic toys, but when the batteries die, the toys live on, still powered by the energy of children at play.

Among living Americans, there are only two "generations"

"The ________ Generation” has long been one of those red-flag phrases, a strong indicator that you may be about to encounter serious bullshit. There are occasions when it makes sense to group together people born during a specified period of 10 to 20 years, but those occasions are fairly rare and make up a vanishingly small part of the usage of the concept.

First, there is the practice of making a sweeping statement about a "generation" when one is actually making a claim about a trend. This isn't just wrong; it is the opposite of right. The very concept of a generation implies a relatively stable state of affairs for a given group of people over an extended period of time. If people born in 1991 are more likely to do something that people born in 1992 and people born in 1992 are more likely to do it than people born in 1993 and so on, discussing the behavior in terms of a generation makes no sense whatsoever.

We see this constantly in articles about "the millennial generation" (and while we are on the subject, when you see "the millennial generation," you can replace "may be about to encounter serious bullshit" with "are almost certainly about to encounter serious bullshit"). Often these "What's wrong with millennial's?" think pieces manage multiple layers of crap, taking a trend that is not actually a trend and then mislabeling it as a trait of a generation that's not a generation.

How often does the very concept of a generation make sense? Think about what we're saying when we use the term. In order for it to be meaningful, people born in a given 10 to 20 year interval have to have more in common with each other than with people in the preceding and following generations, even in cases where the inter-generational age difference is less than the intra-generational age difference.

Consider the conditions where that would be a reasonable assumption. You would generally need society to be at one extreme for an extended period of time, then suddenly swing to another. You can certainly find big events that produce this kind of change. In Europe, for instance, the first world war marked a clear dividing line for the generations.

(It is important to note that the term "clear" is somewhat relative here. There is always going to be a certain fuzziness with cutoff points when talking about generations, even with the most abrupt shifts. Societies don't change overnight and individuals seldom fall into the groups. Nonetheless, there are cases where the idea of a dividing line is at least a useful fiction.)

In terms of living Americans, what periods can we meaningfully associate with distinct generations? I'd argue that there are only two: those who spent a significant portion of their formative years during the Depression and WWII; and those who came of age in the Post-War/Youth Movement/Vietnam era.

Obviously, there are all sorts of caveats that should be made here, but the idea that Americans born in the mid-20s and mid-30s would share some common framework is a justifiable assumption, as is the idea that those born in the mid-40s and mid-50s would as well. Perhaps more importantly, it is also reasonable to talk about the sharp differences between people born in the mid-30s and the mid-40s.

There are a lot of interesting insights you can derive from looking at these two generations, but, as far as I can see, attempts to arbitrarily group Americans born after, say, 1958 (which would have them turning 18 after the fall of Saigon) is largely a waste of time and is often profoundly misleading. The world continues to change rapidly, just not in a way that lends itself toward simple labels and categories.

First, there is the practice of making a sweeping statement about a "generation" when one is actually making a claim about a trend. This isn't just wrong; it is the opposite of right. The very concept of a generation implies a relatively stable state of affairs for a given group of people over an extended period of time. If people born in 1991 are more likely to do something that people born in 1992 and people born in 1992 are more likely to do it than people born in 1993 and so on, discussing the behavior in terms of a generation makes no sense whatsoever.

We see this constantly in articles about "the millennial generation" (and while we are on the subject, when you see "the millennial generation," you can replace "may be about to encounter serious bullshit" with "are almost certainly about to encounter serious bullshit"). Often these "What's wrong with millennial's?" think pieces manage multiple layers of crap, taking a trend that is not actually a trend and then mislabeling it as a trait of a generation that's not a generation.

How often does the very concept of a generation make sense? Think about what we're saying when we use the term. In order for it to be meaningful, people born in a given 10 to 20 year interval have to have more in common with each other than with people in the preceding and following generations, even in cases where the inter-generational age difference is less than the intra-generational age difference.

Consider the conditions where that would be a reasonable assumption. You would generally need society to be at one extreme for an extended period of time, then suddenly swing to another. You can certainly find big events that produce this kind of change. In Europe, for instance, the first world war marked a clear dividing line for the generations.

(It is important to note that the term "clear" is somewhat relative here. There is always going to be a certain fuzziness with cutoff points when talking about generations, even with the most abrupt shifts. Societies don't change overnight and individuals seldom fall into the groups. Nonetheless, there are cases where the idea of a dividing line is at least a useful fiction.)

In terms of living Americans, what periods can we meaningfully associate with distinct generations? I'd argue that there are only two: those who spent a significant portion of their formative years during the Depression and WWII; and those who came of age in the Post-War/Youth Movement/Vietnam era.

Obviously, there are all sorts of caveats that should be made here, but the idea that Americans born in the mid-20s and mid-30s would share some common framework is a justifiable assumption, as is the idea that those born in the mid-40s and mid-50s would as well. Perhaps more importantly, it is also reasonable to talk about the sharp differences between people born in the mid-30s and the mid-40s.

There are a lot of interesting insights you can derive from looking at these two generations, but, as far as I can see, attempts to arbitrarily group Americans born after, say, 1958 (which would have them turning 18 after the fall of Saigon) is largely a waste of time and is often profoundly misleading. The world continues to change rapidly, just not in a way that lends itself toward simple labels and categories.

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Two Napoleons and a Potemkin village

I wish I remembered the exact context, but a few years ago I was listening to a radio interview on the subject of delusion. At one point, the reporter asked "what happens when two mental patients who both think they are Napoleon meet each other?" The expert replied, "After careful consideration, both patients come to the correct conclusion: the other guy is crazy."

That anecdote came to mind recently when reading this piece in New York magazine by Benjamin Wallace profiling the troubles at Hyperloop One. [Longtime readers will remember this is not the first time we've called out New York's Hyperloop coverage.]

There is, course, another "hyperloop" company in the news. Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, but as Shervin Pishevar (venture capitalist and co-founder of Hyperloop One) told the generally credulous reporter, the other company didn't really have a serious chance of building anything of consequence.

The dismissive tone might have had a bit more resonance if it hadn't been followed almost immediately by this description of how Hyperloop One prepared for its big moment in the sun

[Emphasis added]

As if this weren't bad enough, the article then goes on to quote engineers for the company admitting what many of us have been saying all along: that the incredibly over-hyped demonstration was entirely limited to the parts of the technology everyone already knew worked. Rather than being a test, it was, in reality, little more than a glorified science fair exhibit.

In case I was a bit obscure in the title...

That anecdote came to mind recently when reading this piece in New York magazine by Benjamin Wallace profiling the troubles at Hyperloop One. [Longtime readers will remember this is not the first time we've called out New York's Hyperloop coverage.]

There is, course, another "hyperloop" company in the news. Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, but as Shervin Pishevar (venture capitalist and co-founder of Hyperloop One) told the generally credulous reporter, the other company didn't really have a serious chance of building anything of consequence.

[a] crowdsourced, volunteer-staffed company with a confusingly similar name, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies. It was perhaps not a serious long-term threat — the company was run by a former Uber driver and a former Italian MTV VJ — but Hyperloop Transportation Technologies had a few months’ head start over Hyperloop Technologies, and the amateurish nature of his rivals didn’t help Pishevar in the credibility game, which he recognized was, at this point, the entire game.

The dismissive tone might have had a bit more resonance if it hadn't been followed almost immediately by this description of how Hyperloop One prepared for its big moment in the sun

[Emphasis added]

Pishevar knew the power of a well-placed media exclusive to lubricate the creation of something from nothing. In fact, he had been keeping Forbes technology editor Bruce Upbin up to date on every development of his new venture since its infancy. “Shervin mentioned the Forbes piece early, maybe even the first day I met him,” BamBrogan remembers. By early 2015, Pishevar’s company was a few steps further along, having hired a general counsel (Pishevar’s brother Afshin, who was bunking in BamBrogan’s spare bedroom) and raised $7.5 million, primarily from Pishevar’s Sherpa Capital and from Formation 8, a VC firm run by the investor Joe Lonsdale. But the company was still in BamBrogan’s garage, with no health insurance, no company insurance, no HR processes, no website, and no office space. The only thing holding it together, at this point, was Pishevar’s estimable sales skills. With a big Forbes story now slated for imminent publication, the company was in a race to acquire enough of a patina of substantiality to merit prominent coverage in America’s most famous business magazine. “It was crazy,” BamBrogan recalls. “We’re spending time finding the right industrial space that we want to grow into but also that we can do for this Forbes shoot.”

A recently hired director of operations knew the landlord of a large campus in downtown L.A., and at the end of the month, BamBrogan and his handful of colleagues moved into a sliver of the space, a 6,500-square-foot former ice factory, before they had secured a lease. With the magazine deadline looming, the skeleton crew were unrolling carpets, BamBrogan was making repeated trips to Ikea in his Audi sedan to buy 16 Vika Amon tables and 64 Vika Adil legs, and the company was buying 25 computers and 50 monitors. Some of the computers had only one graphics card and couldn’t actually run two monitors, but the superfluous equipment beefed up the apparent size of the company. The day of the shoot, BamBrogan and his co-workers scheduled a flurry of job interviews in the office so that more people would be around.

As if this weren't bad enough, the article then goes on to quote engineers for the company admitting what many of us have been saying all along: that the incredibly over-hyped demonstration was entirely limited to the parts of the technology everyone already knew worked. Rather than being a test, it was, in reality, little more than a glorified science fair exhibit.

In case I was a bit obscure in the title...

In politics and economics, a Potemkin village (also Potyomkin village, derived from the Russian: Потёмкинские деревни, Russian pronunciation: [pɐˈtʲɵmkʲɪnskʲɪɪ dʲɪˈrʲɛvnʲɪ] Potyomkinskiye derevni) is any construction (literal or figurative) built solely to deceive others into thinking that a situation is better than it really is. The term comes from stories of a fake portable village, built only to impress Empress Catherine II during her journey to Crimea in 1787. While some modern historians claim accounts of this portable village are exaggerated, the original story was that Grigory Potemkin erected the fake portable settlement along the banks of the Dnieper River in order to fool the Russian Empress.

Monday, December 19, 2016

Charter schools and astroturf

There's nothing particularly exceptional about the following story – if anything, it's pretty much par for the course – but it is a reminder of something that we all know on some level but often fail to acknowledge. There is a huge imbalance in the per-school money available for charters versus traditional public schools. This would always be a concern but under the current system it is nothing short of a fatal flaw. Today, schools with large lobbying budgets for getting funding approved and large advertising budgets for attracting students (particularly those who are likely to improve the schools' test scores) are at such an advantage that they can easily push other schools into a death spiral of budget cuts and dwindling enrollment.

If we want to have charters as a part of a functioning education system, we need to reform that system in a way that minimizes the impact of deep pockets rather than amplifies it.

If we want to have charters as a part of a functioning education system, we need to reform that system in a way that minimizes the impact of deep pockets rather than amplifies it.

The cost to bus charter school students and advocates to rallies: $87,870.

The cost of providing them food from Subway: $14,040.

The cost of launching a media blitz including a new wave of television advertisements after state legislators failed to recommend funding new charter schools: $300,429.

The impact on students “trapped in failing schools” if this campaign drives funding to greatly expand charter school enrollment: Priceless, says Families for Excellent Schools, the nonprofit organization behind the effort.

According to spending reports filed with the Office of State Ethics Monday, the organization spent $413,000 in April — more than double what the organization spent during the first three months of the legislative session. This brings the organization’s spending to $667,000 so far this year. Add in what other groups advocating for charter schools are spending, and the total nears $1 million.

Saturday, December 17, 2016

The future of Faraday Future is questionable

Exceptional work by Raphael Orlove of Jalopnik.(the spirit of Gawker lives on). The whole article is highly recommended.

Sources close to Faraday Future, including suppliers, contractors, current, prospective and ex-employees all spoke to Jalopnik over a number of weeks on conditions of anonymity and said the money has been M.I.A., the plans are absurd and the organization verges on the dysfunctional.

A year ago, things seemed very different. In late November of 2015, Faraday Future burst onto the scene with promises as big as its name was mysterious.

Staffed by prominent industry figures poached from companies like Tesla, Apple, Ferrari and BMW, FF made bold, unprecedented promises: an electric car that could not only drive itself but connect to its owner’s smartphone and learn from their daily habits to become the ultimate personalized vehicle. And if ownership didn’t suit their lifestyle, fine; the company was eager to expand into ride-sharing and autonomous fleet services.

With a $1 billion facility in Nevada, the company promised production by 2017. Forget what you know about cars, the teaser videos proclaimed. A revolution is coming and we would see it at the CES trade show in Las Vegas. Everyone anticipated an actual car that could live up to these claims.

Then January and CES rolled around and the company revealed that yes, that wild rocket-looking supercar that leaked onto the internet via an app really was Faraday Future’s show car. But not its actual production car. That would come later, the company swore after an embarrassing debut that laid the hype and the buzzwords on thick but had seemingly little to back it up. In the meantime the company promised a “skateboard” modular electric platform that could be adapted to suit several different body styles.

But everything would be fine, right? After all, FF was getting $335 million in state tax incentives and abatements from Nevada for its plant, and it was sponsoring a Formula E team. And in the company’s own words, it would do for cars what the iPhone did for communications in 2007. And Faraday Future is funded by Jia Yueting, a tech mogul in China known for starting the country’s first paid video streaming service. It’s often nicknamed “The Netflix of China,” and it brought Jia the billions he needed to start a whole tech empire, selling everything from smartphones to TVs to cars.

What could go wrong?

That was in January. FF spent the next several months in the news over and over again, almost always for reasons no company wants to be in the news. There was the lag on payments to the factory’s construction company, the senior staffers jumping ship, the confusing debut of a seemingly competing car from the company helmed by its principal backer, the lawsuits from a supplier and a landlord who said they weren’t getting paid, the work stoppage on the factory, the state officials in Nevada who said Jia didn’t have as much money as he claimed (something that Jia denied in a haters-are-my-motivators statement), and the fact that leaders in that state copped to never really knowing much about FF’s financials before approving that incentive package.

...

I wish I could say this in front of every sentence I write about Faraday Future, but from everything I’ve seen there is good and serious engineering work getting done at the company.

If anything, Faraday Future has too many people working on one of the most interesting cars we’ve seen in years, engineers crammed computer to computer, even on fold up-picnic tables as one anonymous interviewee told Jalopnik. All-electric, eyes on autonomy, with incredible performance and design. “There’s a lot of good people there,” one source noted. “That’s the worst part.”

But you can’t have this engineering side without a solid business to back it up, and the good work at Faraday Future seems like it has been constantly undone by the unrealistic demands of its top leadership and a money gulf across the Pacific.

Friday, December 16, 2016

Despite what Munroe says about the industry group, it's still less effective at lobbying than Disney's

Remember this?

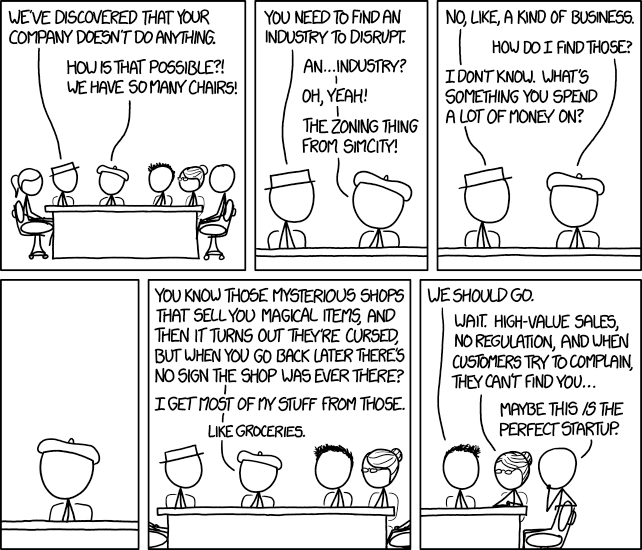

I've been meaning to work up a thread on magical thinking in business culture and journalism. Leave it to XKCD to get there first.

The thinking of business writers has become so muddled and, in places, so overtly mystical that the important fundamental drivers are completely lost in the discussion. Words like "disruptor" or "transformative" have such tremendous emotional resonance for the writers (and investors) that they blind them to the underlying business forces.

I've been meaning to work up a thread on magical thinking in business culture and journalism. Leave it to XKCD to get there first.

Thursday, December 15, 2016

"Disruption" is now officially a dead metaphor

DYING METAPHORS. A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically ‘dead’ (e. g. iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgel for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a ‘rift’, for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying. Some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning without those who use them even being aware of the fact. For example, toe the line is sometimes written as tow the line. Another example is the hammer and the anvil, now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: a writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase.We've been heading toward this for a long time. From the beginning, the idea of disruption never explained nearly as much as it was supposed to. There were always as many exceptions as cases and much of the appeal of the idea could be attributed to the way it played into popular narratives about visionary innovators.

George Orwell

By now, the term has been so overused that it has lost all meaning. Here's Jill Lepore writing for the New Yorker.

Ever since “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” everyone is either disrupting or being disrupted. There are disruption consultants, disruption conferences, and disruption seminars. This fall, the University of Southern California is opening a new program: “The degree is in disruption,” the university announced. “Disrupt or be disrupted,” the venture capitalist Josh Linkner warns in a new book, “The Road to Reinvention,” in which he argues that “fickle consumer trends, friction-free markets, and political unrest,” along with “dizzying speed, exponential complexity, and mind-numbing technology advances,” mean that the time has come to panic as you’ve never panicked before. Larry Downes and Paul Nunes, who blog for Forbes, insist that we have entered a new and even scarier stage: “big bang disruption.” “This isn’t disruptive innovation,” they warn. “It’s devastating innovation.”

Obviously, sense has been draining away for a long time, but the term officially flat-lined when the heads of AT&T and Time Warner headed to DC to defend the indefensible. From the must-read Gizmodo piece by Michael Nunez.

In front of the Senate subcommittee today, AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson brazenly dismissed concerns of potentially anticompetitive behavior. The bespectacled executive, according to a New York Times report, told lawmakers that the merger would “disrupt the entrenched pay-TV models” and give customers more options.

The truth is a little more complicated than that. AT&T is already the second-largest US telecommunications company (with 133.3 million subscribers) and the largest pay-TV service in the US and the world. If it merged with Time Warner, the second-largest broadband provider and third-largest video provider in the US, it would create a media conglomerate with unspeakable power. Critics say it would be a conglomerate that many companies just couldn’t compete with.

We are truly into Newspeak territory here. The sole purpose of this type of mergers is to entrench position and prevent the industry from being disrupted. Those at the top quite accurately view disruption as a serious and possibly existential threat to the status quo. If you can now use the term to describe a mega-merger, it has no meaning left at all.

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Vanishing overhead bins in the upsell economy

From Matt Novak

I don't have access to the actual numbers, of course, but as a former marketing guy, I strongly suspect that real money here is not coming from that 20 bucks or so you pay to put a carry-on bag in the overhead compartment. Instead, it comes from the way that policies like this screw with consumers' decision-making ability.

This works on at least three levels:

1. Fees make pricing more opaque. Sometimes, additional costs may be completely unexpected – you go to pay your bill and find its much larger than what you thought you had agreed to – but even when you know something is coming, those fees make it difficult to know exactly how much you will be handing over.

2. These policies greatly complicate the calculations consumers need to perform. Despite what you might occasionally hear from some freshwater economist, the human brain has finite computing power. If the computations required to determine the optimal purchase get too long and involved, people are more likely to resort to shortcuts or simply start making mistakes.

3. A crappy product is the first step in the road to upgrade riches. This is not all that different from classic bait-and-switch scam we are all familiar with, but the potential payoff is much greater. Tiered systems offer enormous potential for convincing people to pay way too much money for things they don't particularly want. By making that bottom level product sufficiently unattractive, you can get a lot of customers into the upgrade habit. Just ask your local cable company.

United has announced a “new tier” of ticket, as the company calls it. The airline’s cheapest flights will now be called Basic Economy, and if you want to store something in the overhead bin, that’ll cost you extra. Passengers will be able to bring a carry-on that fits underneath the seat in front of them. But don’t even think about putting something above you. That’s for people who paid more.

Of course, the airline is positioning this move as providing “more options” for customers. But it seems like providing more “choice” always comes with a fee for something customers used to get for free.

“Customers have told us that they want more choice and Basic Economy delivers just that,” Julia Haywood, executive vice president at United said in a hilarious news release. “By offering low fares while also offering the experience of traveling on our outstanding network, with a variety of onboard amenities and great customer service, we are giving our customers an additional travel option from what United offers today.”

Want to hear another fun aspect of “choice” that Basic Economy provides? Passengers won’t get an assigned seat until the day they depart.

I don't have access to the actual numbers, of course, but as a former marketing guy, I strongly suspect that real money here is not coming from that 20 bucks or so you pay to put a carry-on bag in the overhead compartment. Instead, it comes from the way that policies like this screw with consumers' decision-making ability.

This works on at least three levels:

1. Fees make pricing more opaque. Sometimes, additional costs may be completely unexpected – you go to pay your bill and find its much larger than what you thought you had agreed to – but even when you know something is coming, those fees make it difficult to know exactly how much you will be handing over.

2. These policies greatly complicate the calculations consumers need to perform. Despite what you might occasionally hear from some freshwater economist, the human brain has finite computing power. If the computations required to determine the optimal purchase get too long and involved, people are more likely to resort to shortcuts or simply start making mistakes.

3. A crappy product is the first step in the road to upgrade riches. This is not all that different from classic bait-and-switch scam we are all familiar with, but the potential payoff is much greater. Tiered systems offer enormous potential for convincing people to pay way too much money for things they don't particularly want. By making that bottom level product sufficiently unattractive, you can get a lot of customers into the upgrade habit. Just ask your local cable company.

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

Thomas Friedman blogging IV – – good tech is friendly tech

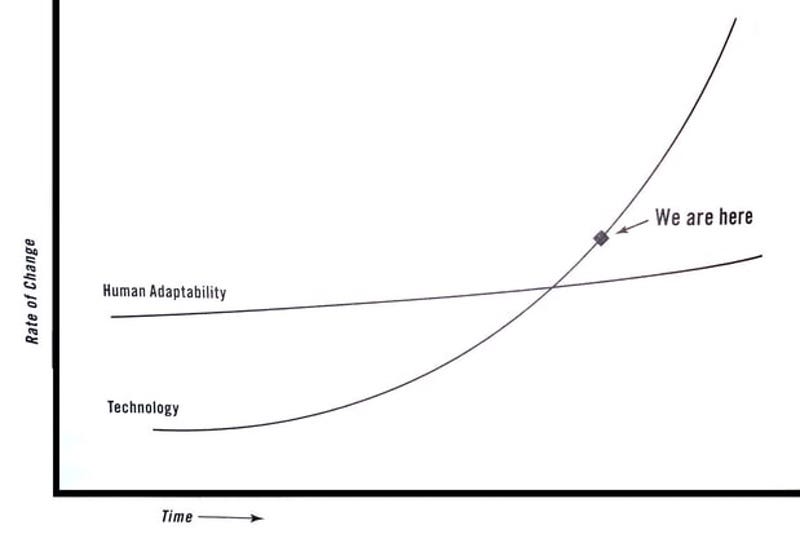

Though it is a bit of a side issue, there is another flaw in Thomas Friedman's argument that I'd like to address, as much for future reference as anything else (I plan on getting back to some of these larger questions).

As is been noted previously by others, Friedman's technology is a big, generic, undefined thing. A mysterious godlike force which must be accommodated lest ye be afflicted with Luddite cooties. Commentators like Friedman seldom think of technology as a set of tools, but that's exactly the appropriate framework.

The idea that human adaptability needs to be proportional to technological change is wrong in multiple ways. Advances in technology should produce tools that are more powerful, cheaper, and generally easier to use. All other things being equal, better tech should require less adaptability than less sophisticated tech. Whether we are talking about automatic transmissions or USB ports or natural language processing, the objective is to make things easier.

It's important to step back for a moment at this point and distinguish between the adapting that an individual has to do and what a society has to do collectively. Even the most tech savvy among us struggle now and then with a new development, but if we really are talking about an advance, the learning curve on the new technology should be better than the learning curve on the old.

More excellent work from Adam Conover

Yet another example of a comedian producing better journalism than most journalists.

Monday, December 12, 2016

Thomas Friedman blogging III – – a few words from Matt Novak

I don't buy all of Novak's take on this (more on that later if I get around to it), but, on the whole, this is an exceptionally sharp analysis:

The adoption rates of early and mid-20th Century consumer technology are even more impressive when you consider infrastructure. I'd argue that the percentage of American households with mechanical refrigerators in 1939 is, in many ways, less relevant than the percentage of electrified households with refrigerators that year. By the same token, a large part of the country didn't get TV stations until the mid-50s and yet we still hit 59%. Viewed this way, consumers were considerably more eager to adopt new technology in the mid-2oth Century than they are today.

Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi first flagged the graph in a blog post today. The graph shows technology (which is never defined) and its rate of change (which is never defined) and human adaptability (which is never defined). It’s the kind of thing you might see scrawled in feces in Ted Kaczynski’s prison cell but it’s now been conveniently committed to paper and given a much wider audience.

...

The truth is that technological adoption isn’t necessarily speeding up. Just look at consumer goods like television. In 1950 just 8 percent of Americans had a TV. Four years later, in 1954, a whopping 59 percent of American households had a TV. Here we are on the cusp on 2017 and I’m having a hard time thinking of any consumer technology that made any comparable jump since 2012.

Or let’s go back further. The Great Depression was a desperate time for most Americans. But technological leaps didn’t stop. Look at the mechanical refrigerator as another example of rapid change in a relatively short period of time. Just 8 percent of American households had a fridge in 1930. By the end of the decade roughly 44 percent had one. People much smarter than myself have argued that refrigeration did more to shape the United States than most other technologies of the 20th century. Yes, smartphones are revolutionary. But refrigeration tech arguably changed America as much, if not more.

The adoption rates of early and mid-20th Century consumer technology are even more impressive when you consider infrastructure. I'd argue that the percentage of American households with mechanical refrigerators in 1939 is, in many ways, less relevant than the percentage of electrified households with refrigerators that year. By the same token, a large part of the country didn't get TV stations until the mid-50s and yet we still hit 59%. Viewed this way, consumers were considerably more eager to adopt new technology in the mid-2oth Century than they are today.

Friday, December 9, 2016

Cracked's interesting but self-refuting argument

"Why Pop Science Matters - Lowest Common Dominator"

I've got some thoughts on this, but to avoid any

spoilers, we'll talk about it after the break.

Thursday, December 8, 2016

Essential tech reporting at Gizmodo [Facebook edition]

William Turton has a series that you really need to be following. The first and the third articles address Facebook's fake news problem. The second describes how the company managed to spin a failed test of a major initiative as an unqualified success.

In a related article, Michael Nunez describes how the company slow-walked its response to the fake news problem due to fear of conservative backlash.

Ordinal wealth and the bigger pie fallacy

Picking up on Joseph's recent post (which in turn picked up on Jared Bernstein's earlier post), specifically this part:

A few years ago, we ran a post discussing different ways of viewing wealth. One of the approaches we covered was ordinal wealth, the idea that, in some situations, total wealth might be less important (or a less useful metric) than wealth-rank. In terms of social status, political power, and personal satisfaction, being the richest man in town with say $10 million in the bank might be preferable to having $15 million but not breaking the top five.

There is no obvious reason why absolute wealth should be a better central metric than ordinal wealth and other relative measures – you can almost certainly find cases where each is appropriate – but if we do allow for the possibility that relative measures might sometimes work better, all sorts of cherished economic truths start to look fairly shaky.

Maybe I'm missing something, but pretty much all the assurances we've heard about how enlightened self interest will keep us on the right track seem to assume that rational actors will seek to optimize absolute wealth. If the rich and powerful are more concerned with maximizing relative position, it's difficult to see where that enlightenment would come in.

Let's focus on the first sentence. This is a completely conventional assertion and it's entirely valid if you make certain standard (and always implicit) assumptions about what it means to benefit from a transaction. Unfortunately, the reasoning does not stand well when wee start tweaking that assumption.

When the benefits of trade are broadly spread then everyone benefits. But capturing all of the benefits and then using that political power to seize additional benefits is a great way to get very powerful but it runs the risk of undermining the political calculation. After all, if trade is the way that the "rich get richer" and the "poor get even less" then it starts to look like a very bad deal.

A few years ago, we ran a post discussing different ways of viewing wealth. One of the approaches we covered was ordinal wealth, the idea that, in some situations, total wealth might be less important (or a less useful metric) than wealth-rank. In terms of social status, political power, and personal satisfaction, being the richest man in town with say $10 million in the bank might be preferable to having $15 million but not breaking the top five.

There is no obvious reason why absolute wealth should be a better central metric than ordinal wealth and other relative measures – you can almost certainly find cases where each is appropriate – but if we do allow for the possibility that relative measures might sometimes work better, all sorts of cherished economic truths start to look fairly shaky.

Maybe I'm missing something, but pretty much all the assurances we've heard about how enlightened self interest will keep us on the right track seem to assume that rational actors will seek to optimize absolute wealth. If the rich and powerful are more concerned with maximizing relative position, it's difficult to see where that enlightenment would come in.

Wednesday, December 7, 2016

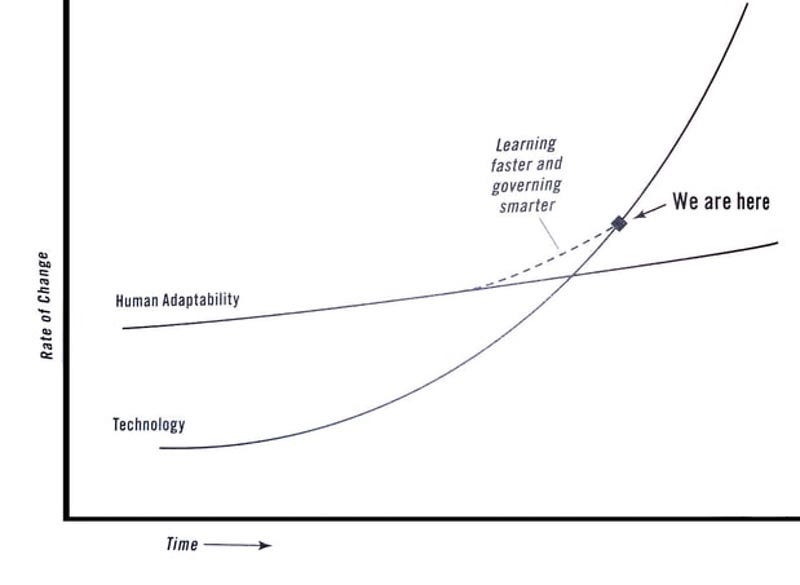

Thomas Friedman blogging II – – failing to learn about "learning faster"

Following up on the previous post, here is a bit of background on the recent, widely-mocked graphs from Thomas Friedman. Though it was the first that prompted the most derision, the second graph might actually merit a bit more attention.

At this point, it is helpful to have a bit of background on Friedman's ideas about modern pedagogy. Friedman has enormous faith in the power of technology to revolutionize education. Unfortunately, he appears to have no idea how antiquated his view of educational technology is, or how badly his ideas have fared in the past. Here's what we had to say on the subject back in 2013.

At this point, it is helpful to have a bit of background on Friedman's ideas about modern pedagogy. Friedman has enormous faith in the power of technology to revolutionize education. Unfortunately, he appears to have no idea how antiquated his view of educational technology is, or how badly his ideas have fared in the past. Here's what we had to say on the subject back in 2013.

75 years of progress

While pulling together some material for a MOOC thread, I came across these two passages that illustrated how old much of today's cutting edge educational thinking really is.

First from a 1938 book on education*:

" Experts in given fields broadcast lessons for pupils within the many schoolrooms of the public school system, asking questions, suggesting readings, making assignments, and conducting test. This mechanize is education and leaves the local teacher only the tasks of preparing for the broadcast and keeping order in the classroom."And this recent entry from Thomas Friedman.

For relatively little money, the U.S. could rent space in an Egyptian village, install two dozen computers and high-speed satellite Internet access, hire a local teacher as a facilitator, and invite in any Egyptian who wanted to take online courses with the best professors in the world, subtitled in Arabic.I know I've made this point before, but there are a lot of relevant precedents to the MOOCs, and we would have a more productive discussion (and be better protected against false starts and hucksters) if people like Friedman would take some time to study up on the history of the subject before writing their next column.

* If you have any interest in the MOOC debate, you really ought to read this Wikipedia article on Distance Learning.

Tuesday, December 6, 2016

The Flawed Premise

This is Joseph.

Jared Bernstein:

Insofar as this point is correct, there is a very short-sighted dynamic going on in modern politics. After all, trade has the potential to greatly improve human life and has been a key element to the development of civilization. Just look at the Silk Road.

When the benefits of trade are broadly spread then everyone benefits. But capturing all of the benefits and then using that political power to seize additional benefits is a great way to get very powerful but it runs the risk of undermining the political calculation. After all, if trade is the way that the "rich get richer" and the "poor get even less" then it starts to look like a very bad deal.

There are stable outcomes that lead to everyone being worse off, and we should guard against them. For trade, I think we need to think very carefully about how we distribute the benefits from trade throughout society.

Jared Bernstein:

The deeply flawed premise through which elites have long operated is that trade is a net plus for everyone as long as the winners compensate the losers. But in the real world, the winners both fail to do so and use their winnings to buy tax and deregulatory policies that further screw the losers.

Insofar as this point is correct, there is a very short-sighted dynamic going on in modern politics. After all, trade has the potential to greatly improve human life and has been a key element to the development of civilization. Just look at the Silk Road.

When the benefits of trade are broadly spread then everyone benefits. But capturing all of the benefits and then using that political power to seize additional benefits is a great way to get very powerful but it runs the risk of undermining the political calculation. After all, if trade is the way that the "rich get richer" and the "poor get even less" then it starts to look like a very bad deal.

There are stable outcomes that lead to everyone being worse off, and we should guard against them. For trade, I think we need to think very carefully about how we distribute the benefits from trade throughout society.

Monday, December 5, 2016

Thomas Friedman blogging I – – it's time to kill the "moonshot" metaphor

[the next few of these come in response to this Matt Taibbi piece in Rolling Stone brought to our attention by Andrew Gelman.]

There is a lot of silliness to unpack here. Friedman has always been really bad on technology. A once solid reporter Peter-Principled into the role of "deep thinker" columnist, he spends his time cheerfully regurgitating flawed conventional wisdom on the subject. This is particularly notable with one of his favorite topics, MOOCs, but more on that later.

For now, though, I want to briefly address a side issue that is been bothering me for a long time, the way Friedman and other writers in the field have come to use the term "moonshot."

If we are talking about Apollo program as a template for projects to advance science and technology, it needs to mean "do something very big on a very aggressive schedule by spending huge amounts of money as fast as you can." Of course, there were other contributing factors, but if you want the bullet point explanation, that's it. For a relatively brief period, political and economic conditions lined up so that the LBJ administration was able to convince the country to let it spend somewhere close to 5% of the federal budget in direct and indirect funding for what was, in the short term, almost entirely a symbolic accomplishment. Even under ideal conditions that was a tough sell.

Did the program eventually pay for itself? Possibly many times over. Most scientific research provides a good return on investment. In terms of immediate payout however, we showed the world that we could beat the Russians to the moon, we produced a genuinely inspirational moment for the nation, and we provided work for as many engineers as the country could supply. That was about it.

The pour-as-much-money-as-possible-as-fast-as-possible-onto-the-problem model does not work equally well in all situations and it may not be the best approach overall, but it was the model for most of the achievements that the "visionaries" of today are so fond of invoking.

Today, "moonshot" has come to mean pick some cool-sounding futuristic project, hype it with a comically vague proposal, a few neat 3-D graphics, and the inevitable TED Talk, then proceed with some half-assed R&D, making sure to give overblown press conferences for anything that can be packaged as an advance. If it all possible, combine the story with a profile of a visionary Silicon Valley billionaire.

The purpose of today's "moonshots" is to make us all feel excited about living on the verge of a bright and wonderful future without actually having to do any of the work or make any of the sacrifices required to bring that future to fruition.

There is a lot of silliness to unpack here. Friedman has always been really bad on technology. A once solid reporter Peter-Principled into the role of "deep thinker" columnist, he spends his time cheerfully regurgitating flawed conventional wisdom on the subject. This is particularly notable with one of his favorite topics, MOOCs, but more on that later.

For now, though, I want to briefly address a side issue that is been bothering me for a long time, the way Friedman and other writers in the field have come to use the term "moonshot."

If we are talking about Apollo program as a template for projects to advance science and technology, it needs to mean "do something very big on a very aggressive schedule by spending huge amounts of money as fast as you can." Of course, there were other contributing factors, but if you want the bullet point explanation, that's it. For a relatively brief period, political and economic conditions lined up so that the LBJ administration was able to convince the country to let it spend somewhere close to 5% of the federal budget in direct and indirect funding for what was, in the short term, almost entirely a symbolic accomplishment. Even under ideal conditions that was a tough sell.

Did the program eventually pay for itself? Possibly many times over. Most scientific research provides a good return on investment. In terms of immediate payout however, we showed the world that we could beat the Russians to the moon, we produced a genuinely inspirational moment for the nation, and we provided work for as many engineers as the country could supply. That was about it.

The pour-as-much-money-as-possible-as-fast-as-possible-onto-the-problem model does not work equally well in all situations and it may not be the best approach overall, but it was the model for most of the achievements that the "visionaries" of today are so fond of invoking.

Today, "moonshot" has come to mean pick some cool-sounding futuristic project, hype it with a comically vague proposal, a few neat 3-D graphics, and the inevitable TED Talk, then proceed with some half-assed R&D, making sure to give overblown press conferences for anything that can be packaged as an advance. If it all possible, combine the story with a profile of a visionary Silicon Valley billionaire.

The purpose of today's "moonshots" is to make us all feel excited about living on the verge of a bright and wonderful future without actually having to do any of the work or make any of the sacrifices required to bring that future to fruition.

Friday, December 2, 2016

More on graphical representations of music

Liszt, Franz: Mephisto Waltz

Here's a different approach.

Aesthetically, I much prefer the first, but I think the second might do a better job conveying information. I have a feeling that I ought to be able to draw a connection between these and graphical representations of more traditional data. Maybe something will come to me over the weekend.

Here's a different approach.

Aesthetically, I much prefer the first, but I think the second might do a better job conveying information. I have a feeling that I ought to be able to draw a connection between these and graphical representations of more traditional data. Maybe something will come to me over the weekend.

Thursday, December 1, 2016

Tom Hanks, creepy CGI Santa Clauses, and the theological canary in the coal mine

I've been making the point for a while now that the evangelical movement that I grew up with in the Bible Belt is radically different from the evangelical movement of today. I was aware that something was changing for a while, but the nature and the extent of the change crystallized for me when I readd this 2004 article from Slate:

Next Stop, Bethlehem?

By David Sarno

The Polar Express is the tale of a boy's dreamlike train ride to the North Pole to meet Santa Claus. Like all stories worth knowing, it's rich enough in image and feeling to accommodate many interpretations. Chris Van Allsburg, the author of the book, calls his story a celebration of childhood wonder and imagination. William Broyles Jr., one of the screenwriters of this year's film version, calls it a kind of Odyssey in which a hero undertakes a mythic, perilous journey of self-discovery. And Paul Lauer, who is a key player in the film's marketing apparatus, sees The Polar Express as a parable for the importance of faith in Jesus Christ.

Lauer's firm, Motive Entertainment, is best known for coordinating the faith-based marketing of The Passion of the Christ. Motive helped spread early word of mouth about the filmby holding screenings for church groups and talking the movie up to religious leaders. When The Passion took in a stunning $370 million at the box office, making it the highest-grossing R-rated film in history, Lauer and his cohorts got a lot of the credit. Earlier this year, Motive was hired by Warner Bros. to promote The Polar Express to Christians. But wait, is The Polar Express an evangelical film?

You'd certainly think so, considering the expansive campaign of preview screenings, radio promotion, DVDs, and online resources that Lauer unfurled in the Christian media this fall. This Polar Express downloads page includes endorsements from pastors and links to church and parenting resources hosted by the Christian media outlet HomeWord. There are suggestions for faith-building activities and a family Bible-study guide that notes, for example, the Boy's Christ-like struggle to get the Girl a train ticket. "The Boy risked it all to recover the ticket," the guide observes. "Jesus gave His all to save us from the penalty of our sins."

HomeWord Radio, which claims to reach more than a million Christian parents daily, broadcast three shows promoting the film. At one point, the show's host wondered excitedly if the movie "might turn out to be one of the more effective witnessing tools in modern times." Motive also produced a promotional package that was syndicated to over 100 radio stations in which Christian recording artists like Amy Grant, Steven Curtis Chapman, and Avalon talked about the movie as they exited preview screenings.

…

Some audience members—and a few Christian film critics—would argue that Santa Claus isn't necessarily a stand-in for Jesus Christ. Last month, Lauer told the Mobile Register that he sees The Polar Express as a parable, "not a movie about belief in God." But when Lauer speaks to a Christian audience, he tells a different story. Lauer told HomeWord Radio that when he asked Robert Zemeckis about all the biblical parallels he was seeing in the film, the director "winked and said, 'Nothing in a movie this big ends up in the script by accident.' " (Zemeckis was traveling and wasn't available for comment.)

This is a spectacular example of getting the pertinent details of the story right and yet completely missing the point. In another piece, the understatement of “Santa Claus isn't necessarily a stand-in for Jesus Christ” would be sharply comic but Sarno seems to be completely oblivious to the joke.

I know we overuse the clip of the minister gunning down Santa in the middle of a children's sermon, but it illustrates an important point.

Over the past few years the evangelical movement has abandoned the majority of its most deeply held theological beliefs (think of how doctrinal differences with Catholics and, even more notably, Mormons have been put aside). It is not at all coincidental the beliefs that were abandoned were uniformly inconvenient from a political standpoint. The conservative movement has both weaponized and secularized the evangelical movement with remarkable success.

Traditionally, evangelicals were more concerned with the potential corruption of their own religion (frequently to the point of paranoia) than with what others were practicing. Christmas was a particularly hot-button issue. In the eyes of several good Southern Baptist ministers, the holiday had become unacceptably commercial, cultural rather than religious, and, in many ways, pagan. Most of the music, imagery, and traditions had nothing to do with the nativity, the "reason for the season." Often, this general hostility toward secular Christmas celebrations focused on Santa Claus.

Like many religious practices, the no-Santa rule could look a bit silly when viewed from the outside, but there's nothing unreasonable about adherents of a particular faith wanting to maintain what they see as the original meaning of a religious holiday. Growing up, I found these attitudes and the little lectures that often accompanied them painfully annoying, but, even though I disagreed, I could see where they were coming from from a theological standpoint.

Now, evangelicalism is a religious movement stripped of its religious elements. There is no scriptural foundation for tax cuts for the rich, deregulating greenhouse gases, or Donald Trump, but those are the defining issue of the movement of today.

Of course, evangelicals are not monolithic. There are many within the movement, some in positions of authority, who object to these obvious deviations from their original core principles. There are indications that the resistance is gaining momentum, and it is entirely possible that in a few years we will have to rethink our assumptions about evangelical Christians and politics. For now, though, this is a cultural (social reactionary) and political (far right) movement, not a religious one, and trying to think of it in any terms that these is misguided.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Forget about faithless electors for a moment; it's the faithful we might need to watch.

I have extremely mixed emotions about "faithless elector" push. I see it as a distraction, it is very probably doomed to fail, and there is a "two wrongs make a right" feeling about the whole thing (just imagine how we would react if the situation were reversed).

My take on this (which has, if anything, been sharpened by recent events) is that we have been negligent about both maintaining the democratic process and protecting it from its opponents. I am more interested in fixing that process for the long-term than in changing the immediate outcome. As of next year, two of our last three presidents will have come into office losing the popular vote. Thanks to gerrymandering, the House has not represented the democratic will of the people for years. The Republicans decision to trash Constitutional norms and long-standing traditions has had a analogous affect on the judiciary. And none of this takes into account the blatant voter suppression efforts of the past few years.

At best, the faithless elector talk might serve as an effective protest against these anti-democratic efforts; at worst, it will simply drain the oxygen from the debate.

On a more personal note there are damned few people out there who are looking to me for normative statements. I've been doing a lot of reflecting as the election, thinking about the role of a statistics blogger in this whole mess. How do we make sure that we are adding value and not simply increasing the noise? One way is for each of us to ask him or herself what unique contributions we bring to the table. If we are all just trying to get our opinions on the record, we might as well all go over to Twitter.

Particularly for a statistics blogger, I believe personal experience and special knowledge can be extraordinarily useful. The combination of an analytic background and an informed perspective can go a long way toward bringing fresh insights and spotting potential problems in conventional arguments. There are few things more valuable for a statistician than having a good sense of what groups should or should not be aggregated and what relationships should or should not be treated as stable.

In my case, that experience includes growing up in the Bible Belt and spending pretty much all of my formative years arguing with fundamentalists. That has given me a strong feel for how evangelicals think. It has also made me more alert to the tremendous, in some cases cataclysmic, changes that have taken place in the movement over the past few years.

The current configuration of the evangelical movement is unstable. Just to be clear, I am not saying that we are about to see a radical shift toward either liberalism or toward the distrust of politics historically associated with groups like the Southern Baptists. When I am saying is that there are great tensions in the movement, that Trump has heightened those tensions, and that while we may not see huge changes in the way we think about religion and politics over the next few years, it would be foolish to rule out the possibility.

Steven Porter writing for the Christian Science Monitor:

Sisneros spells out his position in more detail here and here.

My take on this (which has, if anything, been sharpened by recent events) is that we have been negligent about both maintaining the democratic process and protecting it from its opponents. I am more interested in fixing that process for the long-term than in changing the immediate outcome. As of next year, two of our last three presidents will have come into office losing the popular vote. Thanks to gerrymandering, the House has not represented the democratic will of the people for years. The Republicans decision to trash Constitutional norms and long-standing traditions has had a analogous affect on the judiciary. And none of this takes into account the blatant voter suppression efforts of the past few years.

At best, the faithless elector talk might serve as an effective protest against these anti-democratic efforts; at worst, it will simply drain the oxygen from the debate.

On a more personal note there are damned few people out there who are looking to me for normative statements. I've been doing a lot of reflecting as the election, thinking about the role of a statistics blogger in this whole mess. How do we make sure that we are adding value and not simply increasing the noise? One way is for each of us to ask him or herself what unique contributions we bring to the table. If we are all just trying to get our opinions on the record, we might as well all go over to Twitter.

Particularly for a statistics blogger, I believe personal experience and special knowledge can be extraordinarily useful. The combination of an analytic background and an informed perspective can go a long way toward bringing fresh insights and spotting potential problems in conventional arguments. There are few things more valuable for a statistician than having a good sense of what groups should or should not be aggregated and what relationships should or should not be treated as stable.

In my case, that experience includes growing up in the Bible Belt and spending pretty much all of my formative years arguing with fundamentalists. That has given me a strong feel for how evangelicals think. It has also made me more alert to the tremendous, in some cases cataclysmic, changes that have taken place in the movement over the past few years.

The current configuration of the evangelical movement is unstable. Just to be clear, I am not saying that we are about to see a radical shift toward either liberalism or toward the distrust of politics historically associated with groups like the Southern Baptists. When I am saying is that there are great tensions in the movement, that Trump has heightened those tensions, and that while we may not see huge changes in the way we think about religion and politics over the next few years, it would be foolish to rule out the possibility.

Steven Porter writing for the Christian Science Monitor:

A Texas Republican announced over the weekend that he plans to resign his post as a member of the Electoral College rather than cast a ballot for US President-elect Donald Trump, a man he deems "not biblically qualified for office."

Citing his Christian religion and his understanding of representative democracy, Art Sisneros wrote in a blog post that he could neither vote for Mr. Trump nor break his promise to do so by voting for anyone else. Texas does not require its 38 electors to vote in accordance with the state's presidential election results, but Mr. Sisneros says he made a pledge to the Texas GOP that his vote next month in Austin would follow the will of the general public.

"The reality is Trump will be our President, no matter what my decision is," Sisneros wrote. "Since I can’t in good conscience vote for Donald Trump, and yet have sinfully made a pledge that I would, the best option I see at this time is to resign my position as an Elector."

Sisneros spells out his position in more detail here and here.

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

Terrestrial superstation blogging – – Luken

There are a lot of over the air television stations available in Los Angeles. The last time I helped someone set up an antenna, we were able to pull in 170. Now, most of these are probably channels that you would never watch. English is the language of the plurality but not the majority. Quite a few (though possibly less than you might expect) are shopping channels and their are a few duplicates, stations that appear to or three times on multiple points of the dial.

As the familiar disclaimer reads, individual user experiences may vary. The number and reliability of the channels you will receive is primarily dependent on your location, quality of your antenna, and whether or not you are in the position to put it up on the roof. In some places, you can pull in well over 100 channels with a $.99 pair of rabbit ears. For most parts of town, you'll probably need to spring for a $30 amplified indoor antenna (or hook your TV up to and unamplified outdoor antenna if it still up there after all these years). If you happen to be deep in a canyon or on the wrong side of a mountain (which happens quite a bit around here) you might want to spend the $50-$100 for a good external amplified model.

Personally, I have found you hit a point of diminishing returns somewhere in the middle, and I have never spent more than 35 bucks for a set up.

Even with the best of setups, however, there are still likely to be a few low-powered channels that you never seem to pick up. These LPT the stations tend to collect the more low-budget entries. As compared with the top end of the spectrum exemplified by Weigel Broadcasting and the major studio affiliated channels that prominently feature older but still A-list material like M*A*S*H or Columbo or films from notable directors such as John Ford, Billy Wilder, or Mel Brooks, the poverty row stations generally rely on public domain material, justly forgotten bottom-of-the-catalog shows (such as the Barkleys), and a great deal of Canadian television.

Weigel is the undisputed King of the top end of the spectrum; Luken Broadcasting is arguably the king of poverty row (sort of like a modern day Monogram Studios). With Weigel you get something like NYPD Blue. With Luken, it's more likely to be Police Surgeon (if you were a serious television buff, you'd have heard of this one, but not in a good way).

Luken's networks are filled with absolutely the cheapest programming possible, but they do deserve credit for some real innovation, particularly when it comes to new themes for terrestrial superstations. In addition to Retro TV (a poor man's MeTV), Luken offers a family channel, and outdoors channel, a country music channel, and a gearhead channel. I don't believe I can pick up any of these channels and, even if I could, I probably wouldn't spend much time watching them (though I will admit to a morbid curiosity about whether police surgeon is as bad as everyone says), but it is good that they are out there somewhere.

As we have mentioned many times before, 21st century media has serious monopoly and monopsony issues. Putting aside YouTube for the moment (though that to brings up monopoly and monopsony issues), both content providers and consumers have to rely on a tiny group of major media and telecommunication companies, companies that are both ethically challenged and badly run. Over-the-air television offers an invaluable alternative, a way for independent companies to get stations direct to consumers, and it gives consumers a low or no cost media option.

As the familiar disclaimer reads, individual user experiences may vary. The number and reliability of the channels you will receive is primarily dependent on your location, quality of your antenna, and whether or not you are in the position to put it up on the roof. In some places, you can pull in well over 100 channels with a $.99 pair of rabbit ears. For most parts of town, you'll probably need to spring for a $30 amplified indoor antenna (or hook your TV up to and unamplified outdoor antenna if it still up there after all these years). If you happen to be deep in a canyon or on the wrong side of a mountain (which happens quite a bit around here) you might want to spend the $50-$100 for a good external amplified model.

Personally, I have found you hit a point of diminishing returns somewhere in the middle, and I have never spent more than 35 bucks for a set up.

Even with the best of setups, however, there are still likely to be a few low-powered channels that you never seem to pick up. These LPT the stations tend to collect the more low-budget entries. As compared with the top end of the spectrum exemplified by Weigel Broadcasting and the major studio affiliated channels that prominently feature older but still A-list material like M*A*S*H or Columbo or films from notable directors such as John Ford, Billy Wilder, or Mel Brooks, the poverty row stations generally rely on public domain material, justly forgotten bottom-of-the-catalog shows (such as the Barkleys), and a great deal of Canadian television.

Weigel is the undisputed King of the top end of the spectrum; Luken Broadcasting is arguably the king of poverty row (sort of like a modern day Monogram Studios). With Weigel you get something like NYPD Blue. With Luken, it's more likely to be Police Surgeon (if you were a serious television buff, you'd have heard of this one, but not in a good way).

Luken's networks are filled with absolutely the cheapest programming possible, but they do deserve credit for some real innovation, particularly when it comes to new themes for terrestrial superstations. In addition to Retro TV (a poor man's MeTV), Luken offers a family channel, and outdoors channel, a country music channel, and a gearhead channel. I don't believe I can pick up any of these channels and, even if I could, I probably wouldn't spend much time watching them (though I will admit to a morbid curiosity about whether police surgeon is as bad as everyone says), but it is good that they are out there somewhere.

As we have mentioned many times before, 21st century media has serious monopoly and monopsony issues. Putting aside YouTube for the moment (though that to brings up monopoly and monopsony issues), both content providers and consumers have to rely on a tiny group of major media and telecommunication companies, companies that are both ethically challenged and badly run. Over-the-air television offers an invaluable alternative, a way for independent companies to get stations direct to consumers, and it gives consumers a low or no cost media option.

Monday, November 28, 2016

The myth of orthogonality

One of the factors that contributed to the punched-in-the-gut feeling that so many people had immediately after the election was the seeming orthogonality of the data.

I'm using orthogonal in the broad rather than technical sense here (though I suspect both might apply) meaning to bring new information into the model. It wasn't just that the poll aggregators (with the partial exception of the outlier 538) were all telling us that the outcome was almost certain; we were also hearing exactly the same thing from pretty much everyone else, sources which supposedly had access to different information and were using a variety of approaches. A partial list included prediction markets, expert analyses, pseudo-exit polls (Slate's ill-fated, badly-thought-out Votcastr), and (from what we can infer) the consensus opinions within the campaigns themselves. All of these converged on exactly the same, completely wrong conclusion.

It is likely to take a great deal of hard work and deep digging to uncover exactly what went wrong here, but we can make some educated guesses:

The other data sources were never all that orthogonal (and possibly never all that good). For instance, even under ideal circumstances the predictive power of the markets was always overstated and overhyped, and presidential elections are nowhere near ideal circumstances.

To make matters worse, whatever orthogonality these other sources once brought to the table had faded to nothing by the time we got to this election. Between their early successes and the ludicrous amount of attention they received, the poll aggregators' predictions increasingly dominated conventional wisdom and became the only input (direct or indirect) that mattered for all the other “independent” sources of information.

I suspect that we reached the point where (if you'll forgive a clumsy phrase) prediction markets and the rest were anti-orthogonal. By providing the illusion of independent confirmation of the flawed polling data and likely voter models, they actually made it more difficult to bring new information in the system. It is entirely possible that better informed (or at least less misinformed) voters might have acted very differently, which suggests that the consequences of this particular failure may have been high indeed.

I'm using orthogonal in the broad rather than technical sense here (though I suspect both might apply) meaning to bring new information into the model. It wasn't just that the poll aggregators (with the partial exception of the outlier 538) were all telling us that the outcome was almost certain; we were also hearing exactly the same thing from pretty much everyone else, sources which supposedly had access to different information and were using a variety of approaches. A partial list included prediction markets, expert analyses, pseudo-exit polls (Slate's ill-fated, badly-thought-out Votcastr), and (from what we can infer) the consensus opinions within the campaigns themselves. All of these converged on exactly the same, completely wrong conclusion.

It is likely to take a great deal of hard work and deep digging to uncover exactly what went wrong here, but we can make some educated guesses:

The other data sources were never all that orthogonal (and possibly never all that good). For instance, even under ideal circumstances the predictive power of the markets was always overstated and overhyped, and presidential elections are nowhere near ideal circumstances.

To make matters worse, whatever orthogonality these other sources once brought to the table had faded to nothing by the time we got to this election. Between their early successes and the ludicrous amount of attention they received, the poll aggregators' predictions increasingly dominated conventional wisdom and became the only input (direct or indirect) that mattered for all the other “independent” sources of information.

I suspect that we reached the point where (if you'll forgive a clumsy phrase) prediction markets and the rest were anti-orthogonal. By providing the illusion of independent confirmation of the flawed polling data and likely voter models, they actually made it more difficult to bring new information in the system. It is entirely possible that better informed (or at least less misinformed) voters might have acted very differently, which suggests that the consequences of this particular failure may have been high indeed.

Friday, November 25, 2016

It's not what you'd call a pretty sound...

... but I'd still like to hear one in person.

Wheelharp

[Serious blogging to resume after the holidays.]

Wheelharp

[Serious blogging to resume after the holidays.]

Thursday, November 24, 2016

"As God as my witness..." is my second favorite Thanksgiving episode line [Repost]

If you watch this and you could swear you remember Johnny and Mr. Carlson discussing Pink Floyd, you're not imagining things. Hulu uses the DVD edit which cuts out almost all of the copyrighted music. .

As for my favorite line, it comes from the Buffy episode "Pangs" and it requires a bit of a set up (which is a pain because it makes it next to impossible to work into a conversation).

Buffy's luckless friend Xander had accidentally violated a native American grave yard and, in addition to freeing a vengeful spirit, was been cursed with all of the diseases Europeans brought to the Americas.

Spike: I just can't take all this mamby-pamby boo-hooing about the bloody Indians.

Willow: Uh, the preferred term is...

Spike: You won. All right? You came in and you killed them and you took their land. That's what conquering nations do. It's what Caesar did, and he's not goin' around saying, "I came, I conquered, I felt really bad about it." The history of the world is not people making friends. You had better weapons, and you massacred them. End of story.

Buffy: Well, I think the Spaniards actually did a lot of - Not that I don't like Spaniards.

Spike: Listen to you. How you gonna fight anyone with that attitude?

Willow: We don't wanna fight anyone.

Buffy: I just wanna have Thanksgiving.

Spike: Heh heh. Yeah... Good luck.

Willow: Well, if we could talk to him...

Spike: You exterminated his race. What could you possibly say that would make him feel better? It's kill or be killed here. Take your bloody pick.

Xander: Maybe it's the syphilis talking, but, some of that made sense.

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

This is Joseph

I hadn't been thinking about density like this, but here is a good point about LA:

I hadn't been thinking about density like this, but here is a good point about LA: