Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, August 12, 2011

Stop by and see what you think

A sentence that you just don't want to hear

At this point, it just strikes me as fundamentally unlikely that bold policy innovation is going to come out of the sclerotic United States.

At the time, I mentioned it to Mark (my co-blogger) as one of those sentences that you just don't want to have applied to your country, even in jest. Now Jeffrey Early is willing to ask when was the last time that the United States was a policy innovator. His depressing suggestion is back when Richard Nixon was president.

So here is my question to the blogosphere: what can the United States do to go back to being a leader in policy innovation?

[My own angle is to look at work being done at places like The Incidental Economist to see if we can possibly find an alternative way forward for Health Care Policy]

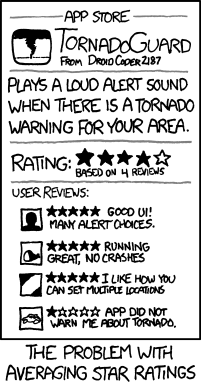

XKCD

Thursday, August 11, 2011

You might not want to read it while you're eating...

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Must-reads

I think we can all use a distraction now

Tax Policy

The wealth that has accrued to those in the top 1 per cent of the US income distribution is so massive that any serious policy program must begin by clawing it back.

If their 25 per cent, or the great bulk of it, is off-limits, then it’s impossible to see any good resolution of the current US crisis. It’s unsurprising that lots of voters are unwilling to pay higher taxes, even to prevent the complete collapse of public sector services. Median household income has been static or declining for the past decade, household wealth has fallen by something like 50 per cent (at least for ordinary households whose wealth, if they have any, is dominated by home equity) and the easy credit that made the whole process tolerable for decades has disappeared. In these circumstances, welshing on obligations to retired teachers, police officers and firefighters looks only fair.

In both policy and political terms, nothing can be achieved under these circumstances, except at the expense of the top 1 per cent. This is a contingent, but inescapable fact about massively unequal, and economically stagnant, societies like the US in 2010. By contrast, in a society like that of the 1950s and 1960s, where most people could plausibly regard themselves as middle class and where middle class incomes were steadily rising, the big questions could be put in terms of the mix of public goods and private income that was best for the representative middle class citizen. The question of how much (more) to tax the very rich was secondary – their share of national income was already at an all time low.

This is actually a very constructive addition to the discussion of how to finance government and society in general. When I was growing up, the general idea we had was that serious tax cuts had to focus on the middle class because that was where all of the money was. But 25% of the national income is a lot and it isn't clear that this type of extreme inequality is socially useful. Few people seem to suggest that we should impoverish the rich, but would it be a horrible world where the top 1% had 15% of the post-tax income?

Monday, August 8, 2011

Bad optics

This final note today, in which S&P beats up on Warren Buffet. The billionaire went on CNBC this morning, said he wasn’t worried at all about the debt downgrade and said, in fact, that the downgrade changed his opinion of S&P — not his opinion of U.S. Treasuries.Funnily enough, couple of hours later, S&P put Buffett’s company Berkshire Hathaway on notice for a possible downgrade.

Hmmm.

Also, we should note here: Berkshire Hathaway’s the single biggest shareholder in S&P’s competitor, Moody’s.

Libertarianism and it's limitations

Well, let me sketch out the logic of Robert Nozick's argument for his version of catallaxy as the only just order. It takes only fourteen steps:

1. Nobody is allowed to make utilitarian or consequentialist arguments. Nobody.

2. I mean it: utilitarian or consequentialist arguments--appeals to the greatest good of the greatest number or such--are out-of-order, completely. Don't even think of making one.

3. The only criterion for justice is: what's mine is mine, and nobody can rightly take or tax it from me.

4. Something becomes mine if I make it.

5. Something becomes mine if I trade for it with you if it is yours and if you are a responsible adult.

6. Something is mine if I take it from the common stock of nature as long as I leave enough for latecomers to also take what they want from the common stock of nature.

7. But now everything is owned: the latecomers can't take what they want.

8. It gets worse: everything that is mine is to some degree derived from previous acts of original appropriation--and those were all illegitimate, since they did not leave enough for the latecomers to take what they want from the common stock of nature.

9. So none of my property is legitimate, and nobody I trade with has legitimate title to anything.

10. Oops.

11. I know: I will say that the latecomers would be poorer under a system of propertyless anarchy in which nobody has a right to anything than they are under my system--even though others have gotten to appropriate from nature and they haven't.

12.Therefore they don't have a legitimate beef: they are advantaged rather than disadvantaged by my version of catallaxy, and have no standing to complain.

13. Therefore everything mine is mine, and everything yours is yours, and how dare anybody claim that taxing anything of mine is legitimate!

14. Consequentialist utilitarian argument? What consequentialist utilitarian argument?

To be able to successfully explain Nozickian political philosophy is to face the reality that it is self-parody, or perhaps CALVINBALL!

It is step 11 that seems to be the most interesting to me. Nobody really wants to argue for anarchy but that doesn't mean that pools of wealth are good, either. I suspect a false dichotomy is present as other options exist as well.

Furthermore, the system also ignores the influence of wealth on process. Differences in prestige, corruption and credibility can lead to issues with step 5, as well. So I think we need to be careful about making property rights primary. Obviously ownership has important effects in making a specific person responsible for an item (otherwise you can get the "Tragedy of the Commons" issues). But that effect works best on small pieces of property that are directly used by the person (a car, a house, a factory) and seem to become less helpful on larger scales (like in a corporation where you need to hire a management team who then bring in principal agent concerns).

Definitely something to consider.

Jonathan Chait: "I suppose I didn't express myself as well as I could have." -- repeatedly

I think Palko's point is pretty obviously just wordplay, but I suppose I didn't express myself as well as I could have.Normally I'd let it rest there (it was one of the more trivial objections I've raised about Chait's position on education), but we really ought to note that this is not the first time we've seen this line:

But being "treated like professionals" has to mean both the opportunity to earn a good living if you do well and the potential to be fired if you fail.You can find the full context of that line and my reaction to it here.

My disconnect with Jon Chait

I think Palko's point is pretty obviously just wordplay, but I suppose I didn't express myself as well as I could have. Being a professional, to most people, means having the opportunity to gain higher pay and recognition with greater success. Such a system also, almost inevitably, entails the possibility of having some consequences for failure. Teaching is very different than most career paths open to college graduates in that it protects its members from firing even in the case of gross incompetence, and it largely denies them the possibility to rise quickly if they demonstrate superior performance.

Obviously the realistic possibility of being fired for gross incompetence would not in and of itself do much to attract more highly qualified teachers, but the opportunity to receive performance-differentiated pay would.

I think I can put my finger on the point of disconnection here. I would gladly take employment In which hard work and results were rewarded (and people who were bad fits were quietly eased out of the profession). These are my favorite work places, as I never want to be in a role where I am not contributing in a substantive way.

But what I think worries me about the attack on teacher tenure is that it seems to be coupled with a small government/austerity movement. I worry that the endgame is no tenure and less compensation (regardless of performance). That approach would open up higher education to worse incentives than it has now and increase the pressure for a parallel (and private) system. Looking at the cost of higher education, my concern is that the poor might be priced out of the education market.

I might be wrong about this pattern, but many countries have balanced job security with quality education (e.g. Canada, Sweden, Finland). I am not against a new pathway, I am just not sure how to increase compensation (to balance against the loss of job security) in the current environment. But I note that Jon Chait is coupling increased compensation opportunities with decreased job security. A reasonable trade, so long as it doesn't fall victim to the desperate need to shrink government that is in the very air these days.

If there is a path forward, I would actually be happy to revisit this question in a positive way. But why is this a burning question in the middle of a period of austerity budgets when it is unclear where the revenue for such reforms would come from?

Another This American Life episode you ought to listen to...

The download is free for the next few days, but you should throw them a few bucks if you can spare it. They do good work.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

The discussion continues

Declining Salaries for Writers

Fifteen years ago, I wrote RPGs for 3 cents a word. In these more modern times, though, the pay rate is... wait, it's still 3 cents a word. Come to think of it, the pay hasn't changed much from the golden age of pulps and early sci-fi. The pay is the same as from the 1950s? What's wrong with this picture?

One argument is 'that is all the market will bear'. Okay, but in that same timeframe, other forms of writing (particularly journalism and non-fiction) moved on to dollar-a-word. Sure, we're in a dip for that sort of writing too, with rates often dropped to half that. But a pair o' quarters per word is still a damn site better than RPGing's 3-cents-per.

The part that makes this discussion so painful is that the quality of writing can really make or break what is fundamentally a book project. This is one place where markets really don't seem to be able to adapt as the low rates often lead to weak product. Maybe this is just a consequence of niche markets?

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Paul Krugman should continue doing more productive things than watching TV

Recently Paul Krugman wrote a smart piece decrying the proliferation of appeal to authority arguments which he closed with the following:

But in any case, this is never an appropriate way to argue — least of all at a time like this, when events have strongly suggested that a lot of work in economics these past few decades, very much including the work on which these guys’ reputations are based, was on the wrong track.

Do I do this myself? Probably on occasion, when I don’t catch myself. But I try not to. I would say that commenters who begin with “I can’t believe that a Nobel prize winner doesn’t understand that …” might want to think a bit harder; mostly, though not always, I have actually thought whatever you’re saying through, and the obvious fallacy you think you’ve found, isn’t. But “Me big famous economist, you nobody” is not a valid argument.

(See John Quiggin and Noah Smith for more on the incident that prompted this)

I'm also always on the lookout for excuses to bring in a favorite video clip, like this one from Whose Line Is It Anyway which provides a great example of the form and nicely shows the respect and affection the cast feel for Caesar.

Just to be absolutely clear, I was:

1. Looking for an excuse to use the "Nobel Prize winner" line in an obviously silly and trivial context;

2. Post the Caesar clip;

3. Link to yet another sharp and well-written Krugman post.

In other words, it was a joke.

(And for the record, if I make a disparaging comment about Felix Salmon followed a Kovacs clip, I'll be joking then too.)