Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Professionals and Advancement

With almost all careers, we expect a certain level of ratcheting advancement. We generally assume that if we maintain a certain quality of work, we will see a more-or-less steady increase in either our compensation, our employability or our job security. This advancement can take all sorts of forms from traditional promotions to a salesman's contact list to a writer's readership, but whatever the form, it is exceedingly rare to find jobs where you start each year about where you started the last one and it's next-to-impossible to find one that would be considered a 'profession.'

(Of course, there are many freshwater economists who are deeply uncomfortable with this ratcheting effect, who would argue that an ideal labor market should have no memory, that the services provided by a long time employee should be treated no differently than any other commodity. Long time OE readers will probably know I don't agree with the idea that labor should be treated as just another market, but that's a topic for another time. For now we're talking about the way things are.)

The discussion of teacher compensation and job security has almost entirely ignored the larger question of advancement, looking at the unusual contractual protections afforded the profession but failing take into account the equally unusual limitations. Take a minute and try to think of professions that have the following career constraints:

Few opportunities to move up the org chart. Not only is the structure here relatively flat, but unlike many industries, the move to management is almost a complete break from your previous role. Thus 'rewarding' the best teachers by making them administrators is a questionable strategy. We obviously need exceptional principals but we can't have teacher career track focused on taking the best teachers out of the classroom;

Non scalable work. Even if you accept claims about class size not mattering (and there's a lot to dispute in the reasoning behind those claims), there are still hard limits to the number of fourth graders one person can teach in a year. Compare this to someone like a journalist who can, in a sense, sell the same piece of work a virtually unlimited number of times;

Bounded compensation. Though movement reformers talk a lot about different incentive pay plans, pretty much all of them are metric based and have pre-determined maximums;

Lack of entrepreneurial opportunities. It is true that administrators can go out and start their own charters but teachers can't start their own classes;

Limited chances for promotion through relocation. This does happen but it's discouraged with good reason. The winners tend to be high-income suburban schools. Add to this the logical results of movement reforms that effectively reduce job security for teachers in schools bad neighborhoods and you have a huge incentive to actually widen the achievement gap.

In other words, we have here another case of advocates for business-based solutions who don't understand how businesses actually operate. Not coincidently, this is also an area where conservatives with actual business experience (like Jim Manzi) tend to take more nuanced positions.

Appropriate Scales

On the other hand, very small variations can look large if the axes covers only the range of variation. The real piece of information that is missing is what is the size of a meaningful change. Maybe we should have graphs declare this extra piece of information so that this point can be discussed along with the variation shown in the graph, itself,

The Wisdom of Salmon

What’s more, everybody wants to be invested in stocks when the market’s going up — just not when it’s going down. Is it possible to actively manage your 401(k) so that you try to go long stocks when they’re going up and then move to cash or bonds when stocks are falling? Well, you can try. But that’s called timing the market, and it tends to end in tears. You are not a hedge-fund manager, and even they get these things wrong. Don’t think you can time the market, because you can’t. So if you want to be invested in up markets, you have to be invested in down markets, too. And as the chart shows, your retirement account will tend to grow most of the time anyway.The main reason for this is that we’re not just sitting back and hoping that the stock market will do all the heavy lifting. Every paycheck, we’re putting money into our 401(k) accounts — about 8.7% of what we earn, on average. And so every quarter, we see our balance rise not just because we’re great at investing, but also because we’re manually adding to the pot.

And in fact that second aspect of saving for retirement is significantly more important — and much more under our own control — than the first aspect. When it comes to our 401(k) plans, people tend to focus far too much on the quarter-to-quarter fluctuations in mark-to-market asset value, rather than trying simply to save as much money as they can for when they’re older. My advice is to think of a retirement account like a piggy bank: you put money in there on a regular basis, and eventually it grows to a substantial sum. Once it’s in there, of course, you try to invest in something reasonably sensible — target-date funds are a pretty good idea, so long as their fees are low. But you don’t have much control over the internal returns on your retirement funds; you do have control over how much you save. So concentrate on the latter more than the former.

The Growth Fetish

It's obvious that our economy is suffering from a lack of growth but for a while now I've come to suspect that in a more limited but still dangerous sense we also overvalue growth and that this bias has distorted the market and sometimes encouraged executives to pursue suboptimal strategies (such as Border's attempt to expand into the British market).

Think of it this way, if we ignore all those questions about stakeholders and the larger impact of a company, you can boil the value of a business down to a single scalar: just take the profits over the lifetime of a company and apply an appropriate discount function (not trivial but certainly doable). The goal of a company's management is to maximize this number and the goal of the market is to assign a price to the company that accurately reflects that number.

The first part of the hypothesis is that there are different possible growth curves associated with a business and, ignoring the unlikely possibility of a tie, there is a particular curve that optimizes profits for a particular business. In other words, some companies are better off growing rapidly; some are better off with slow or deferred growth; some are better off simply staying at the same level; and some are better off being allowed to slowly contract.

It's not difficult to come up with examples of ill-conceived expansions. Growth almost always entails numerous risks for an established company. Costs increase and generally debt does as well. Scalability is usually a concern. And perhaps most importantly, growth usually entails moving into an area where you probably don't know what the hell you're doing. I recall Peter Lynch (certainly a fan of growth stocks) warning investors to put off buying into chains until the businesses had demonstrated the ability to set up successful operations in other cities.

But the idea of getting in on a fast-growing company is still tremendously attractive, appealing enough to unduly influence people's judgement (and no, I don't see any reason to mangle a sentence just to keep an infinitive in one piece). For reasons that merit a post of their own (GE will be mentioned), that natural bias toward growth companies has metastasised into a pervasive fetish.

This bias does more than inflate the prices of certain stocks; it pressures people running companies to make all sorts of bad decisions from moving into markets where you don't belong (Borders) to pumping up market share with unprofitable customers (Groupon) to overpaying for acquisitions (too many examples to mention).

As mentioned before we need to speed up the growth of our economy, but those pro-growth policies have to start with a realistic vision of how business works and a reasonable expectation of what we can expect growth to do (not, for example, to alleviate the need for more saving and a good social safety net). Fantasies of easy and unlimited wealth are part of what got us into this mess. They certainly aren't going to help us get out of it.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Dream a little dream for me

It's a funny story but it has a serious undercurrent. At the risk of sounding like an alarmist, I'm beginning to think that our discourse, our ability exchange and evaluate important information and use it to collectively make informed decisions is in serious trouble, and I'm not sure how you can run a democracy without that.

The decline in journalistic professionalism is a big part of that problem. There are some excellent journalists out there, but there are also far too many like the ones in this story. They nonchalantly build on each other's fictions. They unquestioningly accept claims from interested parties. They dodge responsibility for uncomfortable facts by hiding behind he said/she said stories.

As I've said before, I honestly believe that given good information, the American public tends to make good decisions but there's a corollary to that claim: given the crap we've been fed recently, it's a wonder we still have a country.

And now for a break from serious discussion

Imagine a host talking to a panel of four pundits about someone about to roll a 6-sided die.

Host: What's your prediction for the big dice roll?

Judy: Well, Jim, I've knocked on thousands of doors in this province, and families everywhere are telling me the same thing. They like the number 1, so I expect it to do really well.

Bill: Remember, the big dice roll is taking place on a Sunday after church, so the smart money is on 3, the trinity. We all remember Easter Sunday 1985 when a three was rolled three consecutive times. History is on the side of 3.

Jim: Look at the data. An even number has come up on 9 of the last 13 rolls. You have to play the hot hand on this one and go for 2, 4, or 6.

Alice: I agree with Jim's data, but all that means is that odd numbers are due. Judy is right that 1 is the trendy pick, but I really like 5 as a dark-horse candidate.

[Off-screen a mathematician is sobbing].

And, I suppose, a casino operator is gloating . . .

401(k) plans

The tax break for defined contribution retirement plans will cost the Treasury $212.2 billion between 2010 and 2014, according to the Joint Tax Committee. But the vast amount of that benefit - as much as 80 percent - goes to the top 20 percent of earners, according to estimates from the Tax Policy Center, a nonpartisan, but liberal-leaning, think tank.

For example, a person in the 35 percent tax bracket saves $35 in taxes every time he puts $100 in his 401(k), for a net cost of $65. Someone in the 15 percent bracket pays $85, after tax, for the same $100 contribution. The Pension Rights Center, which has favored traditional defined benefit pensions and other programs aimed at lower-income retirees, advocates rolling back the current $16,500 annual 401(k) tax-deferred contribution limit to the $10,500 level it was at before the Bush tax cuts, its director, Karen Ferguson, has said.

One way to address both the cost and the disparity is to change the deduction into a credit. William Gale, of the Brookings Institution, will present a plan like that to the Senate committee on Thursday. His plan would eliminate the deduction entirely and replace it with a federal match that would be deposited directly into workers retirement accounts. A match of 30 percent would be revenue neutral, he says.

Neither solution is ideal. Lowering the deduction limit makes these plans less able (even in theory) to store enough wealth for retirement. It also makes "catching up" after a period of unemployment or education more difficult.

Matches, on the other hand, are much easier to cut than tax breaks. Dropping the match from 30% to 28% is an easy cut that raises a lot of revenue. It may be harder to penalize post-tax withdrawals, which runs the risk of funds being emptied due to an unexpected job loss.

None of this would really matter if we were confident that social security would be around. It really is the key government anti-poverty program. But ponzi scheme comments are not helping build confidence in the long term health of the program.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Personal Finance talk

Let’s add up how much of the iMac, iPod, iPhone, iBook and iPad profts have been paid out to the owners of Apple. Well lets think. . . oh yes I have it now, ZERO DOLLARS! Not one single penny.

So far is this really different from what Allen Stanford did? I hear some of his investors actually got redemptions. But, I am sure Apple investors will get their money some day, right.

They have the value of their share of the company, but that might very well be spent on other things before any dividends are paid. It's scary to consider.

Even worse is his discussion of Sir Alan Sanford:

You can do whatever you want to Allen Stanford. He is now broke. He got beat up in prison. He may very well spend the rest of his life there. But, he’s 61 years old now. These experience were his life. You can’t take that away.

Once you realize that, you realize the fundamental vulnerability that everyone has in handing over your assets to someone else. There is just no recourse against the other person consuming them.

You have to trust and that’s at the heart of what call The Big Externality.

That is a lot more scary. It really makes the idea of a government sponsored pension program way more appealing. And it definitely makes one skeptical about the ability of a typical investor to manage their assets. After all, I would not have seen Apple as an atypical investment vehicle, mostly because I like and consume their products. But if they are not paying dividends, then the idea behind getting money out of them is entirely to sell shares to somebody else.

But why would they want to buy them if they do not produce returns?

Saturday, September 10, 2011

Remind me not to piss off Felix Salmon

What Robinson nails is the way that this is what Scaramucci does — it’s his job. Scaramucci is a fund-of-funds manager, posting returns even he admits are lackluster: he more or less tracks the S&P 500, while making big, risky bets (a third of his assets are in MBS), investing in leveraged hedge funds, and reserving the right not to redeem his clients’ money upon request. Which means that he only has two ways to make money: either find stupid people to give him their money, or else shower himself with so many conspicuous indicia of success that people just want to buy into his perceived success.

OK, make that one way to make money.

It’s far from clear that Scaramucci actually is successful, in financial terms, by Wall Street standards. He certainly spends a lot — millions of dollars — on various forms of conspicuous consumption and self-promotion. But he’s not making a lot: since he’s a fund-of-funds manager, he’s making 1.5-and-zero, rather than 2-and-20. And under the terms of his deal with Citigroup, a substantial chunk of that 1.5 goes straight to them. He has to run Skybridge, of course, with all the employee compensation, compliance costs, and the like that entails. He’s regularly writing seven-figure checks to pay for things like the Davos Tasting of ludicrously expensive wine. And of course he has to pony up charitable donations, too, so as to be able to get up in front of a well-heeled crowd to receive the Hedge Funds Care Award for Caring. (I’m not making this up.)

Scaramucci’s fake-it-till-you-make-it approach might end up working: his fund is still growing, and Robinson says that he “has become the Wall Street player he aspired to be when he first landed at Goldman some 22 years ago.” He’s living proof of what Windward Capital’s Robert Nichols is quoted saying at the end of the article: “Performance isn’t what beats a path to your door. It’s sales and marketing.”

But he’s not a stock-picker, or even, really, a hedge-fund manager: he just plays one on TV.

Type M Bias

And classical multiple comparisons procedures—which select at an even higher threshold—make the type M problem worse still (even if these corrections solve other problems). This is one of the troubles with using multiple comparisons to attempt to adjust for spurious correlations in neuroscience. Whatever happens to exceed the threshold is almost certainly an overestimate.

I had never heard of Type M bias before I started following Andrew Gelman's blog. But now I think about it a lot when I do epidemiological studies. I have begun to think we need to have a two stage model: one study to establish an association followed by a replication study to estimate the effect size. I do know that novel associations I find often end up diluted after replication (not that I have that large of an N to work with).

The bigger question is whether the replication study should be bundled with the original effect estimate or if it makes more sense for a different group to look at the question in a separate paper. I like the latter more as it crowd-sources science. But it would be better if the original paper was not often in a far more prestigious journal than the replication study, as the replication study is the one that you would prefer to have the the default source for effect size estimation (and thus should be the easier and higher prestige one to find).

Friday, September 9, 2011

Replication in Science

The unspoken rule is that at least 50% of the studies published even in top tier academic journals – Science, Nature, Cell, PNAS, etc… – can’t be repeated with the same conclusions by an industrial lab. In particular, key animal models often don’t reproduce. This 50% failure rate isn’t a data free assertion: it’s backed up by dozens of experienced R&D professionals who’ve participated in the (re)testing of academic findings.

Of course, I worry even more about softer disciplines where the difficulties of replication are much higher (you don;t just have to replicate a lab, you may need to develop an entire new cohort study).

Scary stuff.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Earmarks and Agricultural Research

Like so many bad trends in journalism, the archetypal example comes from Maureen Dowd, this time in a McCain puff piece from 2009. Here's the complete list of offending earmarks singled out by the senator and dutifully repeated by Dowd:

Before the Senate resoundingly defeated a McCain amendment on Tuesday that would have shorn 9,000 earmarks worth $7.7 billion from the $410 billion spending bill, the Arizona senator twittered lists of offensive bipartisan pork, including:Putting aside the relatively minuscule amounts of money involved here, the thing that jumps out about this list is that out of 9,000 earmarks, how few real losers McCain's staff was able to come up with. I wouldn't give the Autry top priority for federal money, but they've done some good work and I assume the same holds for the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Along the same lines, I have trouble getting that upset public monies spent on astronomical research. After that, McCain's selections become truly bizarre. Urban water usage is a huge issue, nowhere more important than in Western cities like Los Vegas and it's difficult to imagine anyone objecting to a program that actually gets kids out of gangs.

• $2.1 million for the Center for Grape Genetics in New York. “quick peel me a grape,” McCain twittered.

• $1.7 million for a honey bee factory in Weslaco, Tex.

• $1.7 million for pig odor research in Iowa.

• $1 million for Mormon cricket control in Utah. “Is that the species of cricket or a game played by the brits?” McCain tweeted.

• $819,000 for catfish genetics research in Alabama.

• $650,000 for beaver management in North Carolina and Mississippi.

• $951,500 for Sustainable Las Vegas. (McCain, a devotee of Vegas and gambling, must really be against earmarks if he doesn’t want to “sustain” Vegas.)

• $2 million “for the promotion of astronomy” in Hawaii, as McCain twittered, “because nothing says new jobs for average Americans like investing in astronomy.”

• $167,000 for the Autry National Center for the American West in Los Angeles. “Hopefully for a Back in the Saddle Again exhibit,” McCain tweeted sarcastically.

• $238,000 for the Polynesian Voyaging Society in Hawaii. “During these tough economic times with Americans out of work,” McCain twittered.

• $200,000 for a tattoo removal violence outreach program to help gang members or others shed visible signs of their past. “REALLY?” McCain twittered.

• $209,000 to improve blueberry production and efficiency in Georgia.

Of course, we have no way of knowing how effective these programs are, but questions of effectiveness are notably absent from McCain/Dowd's piece. Instead it functions solely on the level of mocking the stated purposes of the projects, which brings us to one of the most interesting and for me, damning, aspects of the list: the preponderance of agricultural research.

You could make a damned good case for agricultural research having had a bigger impact on the world and its economy over the past fifty years than research in any other field. That research continues to pay extraordinary dividends both in new production and in the control of pest and diseases. It also helps us address the substantial environmental issues that have come with industrial agriculture.

As I said before, this earmark coverage with an emphasis on agriculture is a recurring event. I remember Howard Kurtz getting all giggly over earmarks for research on dealing with waste from pig farms about ten years ago and I've lost count of the examples since then.

And interspaced between those stories at odd intervals were other reports, less flashy but far more substantial, describing some economic, environmental or public health crisis that reminded us of the need for just this kind of research. Sometimes the crisis is in one of the areas explicitly mocked (look up the impact of industrial pig farming on rural America* and see if you share Mr. Kurtz's sense of humor). Other times the specifics change, a different crop, a new pestilence, but still well within the type that writers like Dowd find so amusing.

Here's the most recent example:

Across North America, a tiny, invasive insect is threatening some eight billion trees. The emerald ash borer is deadly to ash trees. It first turned up in Detroit nine years ago, probably after arriving on a cargo ship from Asia. And since then, the ash borer has devastated forests in the upper Midwest and beyond.* Credit where credit is due. Though not as influential as Dowd, the New York Times also runs Nicholas Kristof who has done some excellent work describing the human cost of these crises.

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

"Ask Mister Math Person"

When a toothache is fatal

A commenter says that according to local news reports, he was quoted a price of $27 for the antibiotic (sounds like erythromycin, then), and $3 for a painkiller. I believe the former, but I have a very hard time swallowing the latter. I mean, I guess I could be wrong, but I am very skeptical that there is a pharmacy out there that sells more than a dose or two of any prescription painkiller for $3. If he chose to take two vicodin over antibiotics, when he must have known that this was not a long-term solution, I have to question his decision-making even more deeply.

But what this illustrates is just how hard it is to make a decision when in extreme levels of pain. I believe the legal term is "diminished capacity". Now, this sort of tragedy can happen under nationalized health care too. But imagine what happens if this type of decision making is extended to emergency rooms?

When good news is a long way away

These long-held concerns are now critical in a decade where the 79 million U.S. people born between 1946 and 1964 start retiring as soon as this year and larger boomer retirement waves build to peak around 2020-2022.

The concern is that the ebb and flow of U.S. stock markets over the past 50 years is highly correlated with the available pool of household savings channeled into equity investment.

Assuming peoples' prime savings years are those between ages 40 and 65, the proportion of the population in that bracket is therefore key to driving the market. As early as the 1980s, economists feared the impact this may have on U.S. housing markets -- and the recent real estate bust may owe it something -- but stock market connections are more convincing.

The data is alarming. Movements in the ratio of these high savers to both retirees and younger adults has presaged long cycles in real equity prices from the downward funk of 1970s to the subsequent 18-year equity boom through the late 1980s and 1990s as boomers swelled the ranks of prime savers.

The worrying bit for the United States is that ratio peaked in 2010.

This may very well be the beginning of the long and painful adjustment suggested in Boom, Bust and Echo. On the academic side, I expect these types of weakening returns to slow retirements, especially as Universities shift more and more to defined contribution pension plans., Mark's excellent post on this makes it rather obvious how unimportant returns are to wealth when they are as low as they are now.

The question is how do we break out of this cycle?

Alternatively, what is the best strategy for those of us who have to try and make some sort of plan for the future under these conditions?

And, finally, with bond yields low and the cost of Social Security baked into the financial system, why is this a good time to talk about privatizing the system? Wouldn't we want to do this in an environment with high rates of return on assets to make the new program have a chance to succeed?

Monday, September 5, 2011

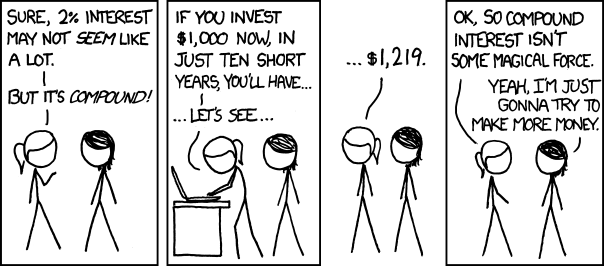

XKCD on investing

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Cassandra in reverse?

Think about it (no time for full links); by reading that section you could have learned, either from the editorial page proper or from the paper’s favorite op-ed guys, that

Clinton’s tax hike would cause a recession and send stocks plunging

Dow 36,000!

American households are saving plenty thanks to capital gains on their houses

Interest rates will soar thanks to Obama’s deficits

And much, much more.

What’s remarkable is that the Journal does not seem to pay a price for this record of awesome wrongness. Maybe subscribers buy the paper for the reporting (although if you ask me, that’s been going downhill since the Murdoch takeover). But as far as I can tell, lots of people still take the editorial page’s pronouncements seriously, even though it seems likely that you could have made a lot of money by betting against whatever that page predicts.

That really does point to an oddity in human culture. Being wrong does not seem to impact on the authority of the source, at least in some groups. That is an unfortunate property as incorrect predictions should make us rethink our internal models rather than reinforce them.

There are complexities here (everyone will have at least some sort of hit rate as even bad predictions are right every once in a while). But it does seem odd that we often double down on bad ideas.

Friday, September 2, 2011

Because it isn't there

I seem to vaguely recall a time when Americans dreamed up big, ambitious projects.

From NPR's The World:

Dubbeling also insists that the Dutch need a new big engineering project.

“Since we stopped reclaiming land from the sea, we Dutch are in some kind of identity crisis. And in the last decades we could export our ideas. But now, with this economic crisis, we really have to think of something different. ”

A mountain, Dubbeling says, definitely qualifies on that score.

Thursday, September 1, 2011

Credentialing versus teaching

Learning is cheaper and easier than ever. And yet getting a degree is more expensive. How’s that? Something’s off, in a big way. Now of course you can push this too far: “Does Yglesias think we don’t need colleges because people can just look things up on Wikipedia instead?” No, I don’t. But I do remember hearing a lot of bluster from old-line media outlets once upon a time that proved to be completely wrong.

I think that the argument about ease of information transfer is right on. That is why a lot of the argument about higher education have settled into "credentialing" and "signaling". Neither of these functions is easier in the internet age and, to some extent, they may be harder (due to more noise and less signal). That makes it very valuable for universities to be able to do these functions.

The problem, as I see it, is that both tasks can be separated from objective outcomes. If you take a program to learn something then that is a concrete and testable outcome. If you take a program to get a credential, then it is quite possible to divorces this from skills or learning (see mail order college degrees).

That is the function that it gets easy to dilute and that could be a very big deal at some point.

Student Debt

The schools sometimes push these students into high-cost private loans that they can never hope to repay, even when they are eligible for affordable federal loans. Because the private loans have fewer consumer accommodations like hardship deferments, the borrowers often have little choice but to default.

Worse yet, these loans and the bad credit history follow the debtors for the rest of their lives. Even filing for bankruptcy doesn’t clean the slate.

I think the experiment with undischargeable debt has been tried many times over history and it never really ends well. Financing higher education is always going to be tricky (due to the large sums involved and the fact that students do not have a credit history). It also doesn't help that students lack assets so it can be an economically rational decision to accept an early career bankruptcy to discharge a six figure debt.

But the opposite extreme is looking increasingly like a bad idea.

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Economics puzzle

We researched the 100 U.S. corporations that shelled out the most last year in CEO compensation. At 25 of these corporate giants, we found, the bill for chief executive compensation actually ran higher than the company's entire federal corporate income tax bill.

Accounting games like "transfer pricing" have sent the corporate share of federal revenues plummeting. In 1945, U.S. corporate income taxes added up to 35 percent of all federal government revenue. This year, corporate income taxes will make up just 9 percent of federal receipts. In 1952, the year Republican President Dwight Eisenhower was elected, the effective income tax rate for corporations was 52.8 percent. Last year it was just 10.5 percent.

Among the nation's top firms, the S&P 500, CEO pay last year averaged $10,762,304, up 27.8 percent over 2009. Average worker pay in 2010? That finished up at $33,121, up just 3.3 percent over the year before.

The last is especially puzzling. When salaries rise faster for a specific category of jobs, it tends to signal that the market is finding a shortage of qualified people. It's also the golden time of opportunity for outsiders to break into the market and drop wages.

Or, option B, it is a feature of rent seeking due to a protected market. Which one strikes out humble reader as more likely?

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

A different point of view on Michael Lewis

My favorite part:

Yet, Germany is a prosperous and pleasant nation to live in; one of the best in the world. Germany manages to have lower unemployment than the US, despite all their unions and socialistic regulations for hiring and firing: laws which Harvard economist ding a lings will insist would be the ruination of the American economy. How did the Germans manage this?

The stuff on Iceland is first rate as well. Definitely worth the read.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

More Freakonomics causality

Since the introduction of the ultrasound in Asia, in the early 1980s, it's often been used to determine the gender of a fetus -- and, if it's female -- have an abortion. In a part of the world with big populations, these sex selection abortions have had a big, unintended consequence.The hypothesis that increasing the ratio of men to women would produce "more sex-trafficking, more AIDS, and a higher crime rate" is entirely reasonable, but like so much observational data there's a big self-selection factor here. Families and women not involved in the sex trade tend to avoid rough neighborhoods and red light districts. There's also a question about outliers -- a few very bad areas with very high male to female ratios.Hvistendahl: I mean there are over 160 million females missing from the population in Asia, and to put that in perspective, it's more than the entire female population of the United States.

So, what happens in a world with too many men? For starters, there's more sex-trafficking, more AIDS, and a higher crime rate. In fact, if you want to know the crime rate in a given part of India, one surefire indicator is the gender ratio. The more men, the more crime. Now, the ultrasound machine didn't create these problems, but it did enable them. So, you have to wonder. What's next?

Once again, the suggestion that changing gender ratios would have significant social consequences makes perfect sense, but if you want to go from sensible suggestion to well-supported hypothesis, it's not enough to mention a fact that points in the right direction; you also have to show how other explanations (self-selection, sampling bias, etc.) can't explain away your fact. That, unfortunately, is where Freakonomics and many other economists-explain-the-world books and articles fail to make the grade.

"Picked so green you could kick them to market"

At the time my grandfather was engaging in a bit of comic hyperbole. These days he might be understating the case (Barry Estabrook, author of Tomatoland, from an NPR interview):

Yeah, it was in southwestern Florida a few years ago, and I was minding my own business, cruising along, and I saw this open-back truck, and it looked like it was loaded, as you said, with green apples.And then I thought to myself wait, wait, apples don't grow in Florida. And as I pulled up behind it, I saw they were tomatoes, a whole truckload mounded over with perfectly green tomatoes, not a shade of pink or red in sight. As we were going along, we came to a construction site, the truck hit a bump, and three or four of these things flew off the truck.

They narrowly missed my windshield, but they did hit the pavement. They bounced a few times, and then they rolled onto the shoulder. None of them splattered. None of them even showed cracks. I mean, a modern-day industrial tomato has no problem with falling off a truck at 60 miles an hour on an interstate highway.

In addition to being tasteless, Estabrook also points out that compared to tomatoes from other sources or from a few decades ago, the modern Florida variety have fewer nutrients, more pesticides (particularly compared to those from California), and are picked with what has been described as 'slave labor' (and given the use of shackles this doesn't seem like much of an exaggeration).

Thursday, August 25, 2011

As problems go, that one really is pretty fundamental

“Groupon’s fundamental problem is that it has not yet discovered a viable business model,” writes Harvard Business School’s Rob Wheeler. “The company asserts that it will be profitable once it reaches scale but there is little reason to believe this.”

More from Salmon on Dalberg

(while you're there, make sure to check out his take-down of Steve Brill.)

From the New Republic. Seriously.

Rick Perry Is a Higher-Education Visionary. Seriously.

I'm way too busy to give this the attention it doesn't deserve but I thought it was a data point worth noting.

Update: Dean Dad (who's generally much more impressed with Kevin Carey than I am) isn't very impressed by Carey's case.

The larger flaw in Carey’s analysis, though, is that it mistakes saying for doing. If Governor Perry really wanted to remake Texas’ higher education system into something more teaching-focused and less research-focused -- a debatable goal, but not an absurd one -- I’d expect to see him beef up the teaching-focusd institutions that already exist. If he shifted state funding from, say, Texas A&M to the state and community colleges, then yes, I could start to buy the argument that he actually means it. If he decided that other parts of the country have the whole “research” thing well in hand, and he wanted to focus Texas on teaching, I’d expect to see him divert money from UT-Austin and send it to the K-12 districts and the community colleges. One could argue the wisdom of that, but at least it would be a vision.

No. He’s endorsing an attack on universities for not being high schools, an attack on community colleges for being high schools, and an attack on K-12 for, well, being there. Yes, some isolated bits of rhetoric could make sense in another context, but that’s not what’s happening. I agree with Carey on the oft-noted paradox that academics who are otherwise liberal become dogmatically, idiotically conservative when discussing their own profession, but their skepticism about Perry is fairer than that. Some of Perry’s rhetoric may be interesting, but at the end of the day, his only vision for higher education is hostility.

Medical Free Markets

Lack of jobs is why everyone feels bad, not because they have less or are poorer or the country isn’t producing or consuming as much. And, not to get to meta – in what I hope is an easily readable post – but an economy that makes lots of people feel bad is by definition a bad economy.

Moreover, the feeling that you have now about the economy is not the feeling of lack of value creation. Its not the feeling of socialism.

I wish I had more time to go into this because “what socialism feels like” is an important concept. However, my more conservative readers will may readily get the following example.

Have you ever been pissed off at the fact that your neighborhood school doesn’t teach any of the stuff you want and it feels like your kid is just wasting her valuable time going to all of these pointless classes for no reason. THAT, is what socialism feels like. That is what the lack of value creation feels like.

Its not that you are afraid of losing what you have or that budget constraints are pinching. Its that the stuff which is available to you sucks. It – in extreme cases – is a world where everyone has a job but where no grocery store has fresh milk. It’s a world where everyone gets a pay check but no one can find shoes that fit.

That is what socialism feels like. That is what government getting in the way of the market feels like. In many ways it’s the exact opposite of the way this feels.

Because you know I can’t resist: When you are waiting in your doctor’s office and she is 50mins late and proceeds to be rude to you and not give you “permission” to go buy the drug that you are dying to buy because its finally been “approved.” That’s what socialism feels like.

It is an important insight that much of the current crisis is not caused by excessive government intervention. Now, it could be true that we could get to a bad place with the addition of excessive government oversight, but I think it is fair to accept that we are not there yet.

That being said, I think the argument about seeing medical doctors (and how familiar this experience is in the US) should give us pause when we argue that the current medical system is free market. It isn't. It's also one of our few areas of growth (which Tyler Cowen sees as rent seeking areas absorbing the unemployed) which is also worth thinking about.

I wonder if we are asking the right questions about the long term?

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

More on Medicare

All told, the cost to the system of raising the Medicare age to 67 would be $11.4 billion in 2014, which is a high price to pay for $5.7 billion in federal savings. It’s exactly a factor of two too high. That’s a massive cost shift. Let’s put it this way, how much would you want to pay for the federal government to save $5.7 billion? I hope your answer is no greater than $5.7 billion. (If not, I’ve got a business proposition for you.) Paying $11.4 billion is a rip off.

It is actually worse than I thought it would be!!

Medical Expenses

The Center On Budget and Policy Priorities’ (CBPP) Paul N. Van de Water is out with a new report warning lawmakers on the Super Committee against considering proposals that would gradually raise the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67 . . .

Van de Water argues that raising the age would actually increase overall system costs and only save the federal government money “by shifting costs to most of the 65- and 66-year-olds who would lose Medicare coverage, to employers that provide health coverage for their retirees, to Medicare beneficiaries, to younger people who buy insurance through the new health insurance exchanges, and to states”

I think that this outcome is obvious from the structure of the problem. It seems obvious to me that single payer systems are able to reduce costs by exerting market power. When I look at procedures, they generally have three costs: out of pocket, insurance reimbursement rates, and medicare rates (in descending order of costs). For a lot of procedures, the costs are thousands of dollars apart.

This is why simply switching to a free market (and going to out of pocket prices) is problematic as a transition (as costs, already the highest in the world, will go up). It also explains why other countries (example: France, Britain, Canada) have decided to go with universal single payer systems: it lower costs (and, if you believe the Incidental Economist, it certainly does not lower quality).

Now it may be that there is a benefit to our current health care system and that other countries may be free riding on our innovations. I am open to this argument. But it is also true that we need to make a decision about what are goals are. If we want to reduce costs (in aggregate) then lowering the medicare eligibility age makes sense (why could it not be 60?).

But if we want to both increase and shift (away from government) the total costs of medical care, that is a lot more concerning. From a societal perspective that seems like an awfully bad deal. It seems unlikely that we are going to increase innovation by all that much by growing the private and medicaid markets by a small fraction. But the costs to those effected by the policy are high.

Why is this a good policy?

Monday, August 22, 2011

More on the vanishing business of writing

Pace Alex, the average quality of newspapers and (published) novels is far, far better than the average quality of blog posts (and—ugh!—comments). This is because people pay for newspapers and novels. What distinguishes newspapers and novels is how much does not get published in them, because people won't pay for it. Payment is a filter, and a pretty good one. Imperfect, of course. But pointing out the defects of the old model is merely changing the subject if the new model is worse.You'll notice that he said novels and not short stories. The business model that allowed people to make a living selling short fiction (something people used to do in this country) has been dead for decades, long before the arrival of online content. Rates for freelancers have been flat for almost as long. For the past fifty years it has gotten increasingly difficult to make a living as a writer.

These are worrisome trends -- I suspect it will take a few more decades to realize just how much the loss of the creative middle class has cost us -- but you can't blame this one on the internet.

Never give money to a company that has a Director of Thought Leadership

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Is there a demographer in the house? -- Texas edition

Anybody care to give it a shot?

Options have a cost associated with them

First, a lack of alternative opportunities can force us to concentrate on developing skills. The kid who spends countless hours practicing football or music becomes much more proficient - and possibly rich - than one who, faced with many opportunities, flits between them and becomes a mere dilettante. A big reason why I got into Oxford - and from there a decent income was a small step - was that, in the days before computer games, I had nothing else to do.

There’s an analogy here with the arts. As Jon Elster points out in Sour Grapes, great art often arises because of constraints. 78 records which limited recordings to three minutes produced lots of great music whereas free jazz and atonality is often unlistenable. Old black and white films with no special effects are often superior to multi-million pound CGI ones. And so on. Excellence often arises from limited choice, and mediocrity from freedom.

I think that this is a very important insight. In sports, we have rules that make the games, themselves, more interesting. A game like Calvinball rapidly becomes uninteresting as one gets older. It is only within a cleanly defined decision space that you can compare degrees of excellence.

I think that this insight has a lot of applications to broader contexts. Removing constraints does not always lead to a uniform improvement in the result. If we took away required classes, I suspect the median student would end up less well educated in epidemiology (is this true for other fields? I'd venture to say that the same would be true in statistics but my exposure beyond that is limited).

I think, as I age, I begin to think that Aristotle (with the ideal of the Golden Mean) was a very clever guy. In particular, it's possible we spend a lot of time comparing two local minima (the two extremes of policy) and ignoring the global maxima (the middle ground between these extremes).

Friday, August 19, 2011

Medicare versus Social Security

At any politically plausible margin, it makes more sense to take $1 out of Medicare than to take it out of Social Security. Social Security checks can be used to buy health care services.

I think that this analysis neglects one key point. Medical care in the United States (or anywhere, for that matter), is hard to bargain with at the time of a procedure (especially an emergent one). It is hard to discuss prices at the ER door during a myocardial infarct, where minutes matter. Here, the real benefit of medicare is the ability to exert market power to set standardized prices (to avoid the power asymmetry otherwise present in medical bargaining).

It is not ideal, but I have not yet come up with a better idea than collective price setting and my own experiences as an uninsured person in the US were certainly eye-opening in this regard. It was amazing how few doctors would even consider accepting cash for services.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Still more intellectual property silliness

From the New York Times:

When copyright law was revised in the mid-1970s, musicians, like creators of other works of art, were granted “termination rights,” which allow them to regain control of their work after 35 years, so long as they apply at least two years in advance. Recordings from 1978 are the first to fall under the purview of the law, but in a matter of months, hits from 1979, like “The Long Run” by the Eagles and “Bad Girls” by Donna Summer, will be in the same situation — and then, as the calendar advances, every other master recording once it reaches the 35-year mark.

The provision also permits songwriters to reclaim ownership of qualifying songs. Bob Dylan has already filed to regain some of his compositions, as have other rock, pop and country performers like Tom Petty, Bryan Adams, Loretta Lynn, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Waits and Charlie Daniels, according to records on file at the United States Copyright Office.

“In terms of all those big acts you name, the recording industry has made a gazillion dollars on those masters, more than the artists have,” said Don Henley, a founder both of the Eagles and the Recording Artists Coalition, which seeks to protect performers’ legal rights. “So there’s an issue of parity here, of fairness. This is a bone of contention, and it’s going to get more contentious in the next couple of years.”

With the recording industry already reeling from plummeting sales, termination rights claims could be another serious financial blow. Sales plunged to about $6.3 billion from $14.6 billion over the decade ending in 2009, in large part because of unauthorized downloading of music on the Internet, especially of new releases, which has left record labels disproportionately dependent on sales of older recordings in their catalogs.

“This is a life-threatening change for them, the legal equivalent of Internet technology,” said Kenneth J. Abdo, a lawyer who leads a termination rights working group for the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences and has filed claims for some of his clients, who include Kool and the Gang. As a result the four major record companies — Universal, Sony BMG, EMI and Warner — have made it clear that they will not relinquish recordings they consider their property without a fight.

“We believe the termination right doesn’t apply to most sound recordings,” said Steven Marks, general counsel for the Recording Industry Association of America, a lobbying group in Washington that represents the interests of record labels. As the record companies see it, the master recordings belong to them in perpetuity, rather than to the artists who wrote and recorded the songs, because, the labels argue, the records are “works for hire,” compilations created not by independent performers but by musicians who are, in essence, their employees.

Independent copyright experts, however, find that argument unconvincing. Not only have recording artists traditionally paid for the making of their records themselves, with advances from the record companies that are then charged against royalties, they are also exempted from both the obligations and benefits an employee typically expects.

And from Andrew Gelman:

Christian Robert points to this absurd patent of the Monte Carlo method (which, as Christian notes, was actually invented by Stanislaw Ulam and others in the 1940s).

The whole thing is pretty unreadable. I wonder if they first wrote it as a journal article and then it got rejected everywhere, so they decided to submit it as a patent instead.

An interesting observation about the electoral math of Texas

And Texas, Tucker notes, “is an unusual electoral landscape”—which is to say it’s nearly empty. The Democratic Party in Texas is nearly nonexistent, and puts up only the most pro forma candidates. (“The Democrats are weak in ways that are not even indicated in the low numbers or poor electoral results,” says Jim Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project and a professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. “As an organization, the Democrats are just—I can’t even come up with a negative enough word.”) And judging from the low turnouts in the Republican primary elections—the only votes in Texas that really count for anything—even the ruling party in Texas is extremely dispirited. In the 2002, 2006, and 2010 votes in which Perry was elected governor, only around 4 percent of the voting-age population turned out for the Republican primary.As a result, Perry only needed to convince roughly 2 percent of the voting-age population of the Republican-heavy state that he would be a suitable governor before cruising through the general elections against a pro forma Democratic candidate, or, in 2006, a slate of nominal candidates. In Texas, the “people who vote in primary elections are unusual people,” Tucker stressed to me. “They are more extreme, further to the right.” In other words, Perry was able to repeatedly vault himself to the governorship largely not because he was a persuasive campaigner, but because he catered to the extreme views of a minority of die-hard conservatives.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Wish I had time to discuss this in detail

When you really want to reach a conclusion

Last conference of the year

Friday, August 12, 2011

Noah Smith has some smart things to say about libertarians and property rights...

That's right: irreducible transaction costs are a fly in the libertarian soup. Completing an economic transaction, however quick and easy, involves some psychological cost; you have to consider whether the transaction is worth it (optimization costs), and you have to suffer the small psychological annoyance that all humans feel each time money leaves their bank account (the same phenomenon contributes to loss aversion and money illusion). Past a certain point, the gains to privatization are outweighed by the sheer weight of transaction cost externalities. (Note that transaction costs also kill the Coase Theorem, another libertarian standby; this is no coincidence.)This dovetails nicely with this discussion about why the decision-making processes of engineers and scientists are often 'irrational' in the strict economics sense of the word. Like transactions, decision-making algorithms have a cost. In most cases, these costs are fairly small (like the few seconds it takes to decide on a brand of beer) and you can get away with ignoring them, but freshwater economists routinely make arguments for rational behavior that require people to make incredibly complicated calculations almost instantly. What's worse, they continue to make these arguments even when data suggests that people are using other, simpler rules to make their decisions.

Stop by and see what you think

A sentence that you just don't want to hear

At this point, it just strikes me as fundamentally unlikely that bold policy innovation is going to come out of the sclerotic United States.

At the time, I mentioned it to Mark (my co-blogger) as one of those sentences that you just don't want to have applied to your country, even in jest. Now Jeffrey Early is willing to ask when was the last time that the United States was a policy innovator. His depressing suggestion is back when Richard Nixon was president.

So here is my question to the blogosphere: what can the United States do to go back to being a leader in policy innovation?

[My own angle is to look at work being done at places like The Incidental Economist to see if we can possibly find an alternative way forward for Health Care Policy]

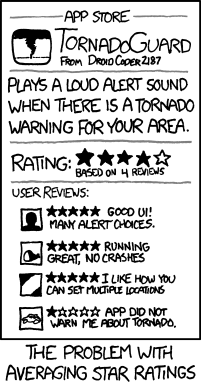

XKCD

Thursday, August 11, 2011

You might not want to read it while you're eating...

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Must-reads

I think we can all use a distraction now

Tax Policy

The wealth that has accrued to those in the top 1 per cent of the US income distribution is so massive that any serious policy program must begin by clawing it back.

If their 25 per cent, or the great bulk of it, is off-limits, then it’s impossible to see any good resolution of the current US crisis. It’s unsurprising that lots of voters are unwilling to pay higher taxes, even to prevent the complete collapse of public sector services. Median household income has been static or declining for the past decade, household wealth has fallen by something like 50 per cent (at least for ordinary households whose wealth, if they have any, is dominated by home equity) and the easy credit that made the whole process tolerable for decades has disappeared. In these circumstances, welshing on obligations to retired teachers, police officers and firefighters looks only fair.

In both policy and political terms, nothing can be achieved under these circumstances, except at the expense of the top 1 per cent. This is a contingent, but inescapable fact about massively unequal, and economically stagnant, societies like the US in 2010. By contrast, in a society like that of the 1950s and 1960s, where most people could plausibly regard themselves as middle class and where middle class incomes were steadily rising, the big questions could be put in terms of the mix of public goods and private income that was best for the representative middle class citizen. The question of how much (more) to tax the very rich was secondary – their share of national income was already at an all time low.

This is actually a very constructive addition to the discussion of how to finance government and society in general. When I was growing up, the general idea we had was that serious tax cuts had to focus on the middle class because that was where all of the money was. But 25% of the national income is a lot and it isn't clear that this type of extreme inequality is socially useful. Few people seem to suggest that we should impoverish the rich, but would it be a horrible world where the top 1% had 15% of the post-tax income?

Monday, August 8, 2011

Bad optics

This final note today, in which S&P beats up on Warren Buffet. The billionaire went on CNBC this morning, said he wasn’t worried at all about the debt downgrade and said, in fact, that the downgrade changed his opinion of S&P — not his opinion of U.S. Treasuries.Funnily enough, couple of hours later, S&P put Buffett’s company Berkshire Hathaway on notice for a possible downgrade.

Hmmm.

Also, we should note here: Berkshire Hathaway’s the single biggest shareholder in S&P’s competitor, Moody’s.