[If this seems a bit dated in places it's because I wrote this a few years ago. I thought I remembered posting it at the time but I recently came across it in my draft folder. Other than missing a few more recent examples, it doesn't seem to have aged much.]

A few years ago, while driving through Oklahoma, I saw a Bible store selling water purification pills. The reason behind that sale was, and is a big story. It affected millions of Americans and continues to have a powerful influence on our politics and yet, with one notable exception, virtually no one in the national press corps noticed.

As some of you might have guessed, the year was 1998 or 1999 and the Bible store was selling water purification tablets because a large part of its clientele thought it was likely that civilization was going to collapse on December 31, 1999.

The best contemporary account probably came from the Wall Street Journal's Lisa Miller:

RAYTOWN, Mo. -- The Rev. Steve Hewitt, an evangelical Christian, preaches a controversial message: The Y2K computer bug is no big deal. "I'm at war to stop the panic," he says.

In the world of conservative Christianity, that stance makes Mr. Hewitt somewhat unorthodox. Some colleagues are prophesying blackouts, martial law, even apocalypse when computers' internal calendars roll over to the year 2000. Meanwhile, Mr. Hewitt, editor and founder of Christian Computing magazine in Kansas City, Mo., is riding the national church circuit counseling people to chill out.

"Airplanes are not going to fall from the sky," he thunders from the front of Spring Valley Baptist Church in Raytown, near Kansas City. "Your car will start. Fire engines will start."

As they did a thousand years ago, some Christians believe that Jesus will come back to Earth around the turn of the millennium accompanied by much tribulation. Suddenly, they are heralding Y2K, which may cause some of the world's computers, power stations and building-control systems to go berserk, as one of the trials that could portend the end of the world.

Meanwhile, evangelists across the nation are advising parishioners to prepare for what Rev. Pat Robertson, of the "700 Club" television program, calls "serious dislocations." A spokeswoman for Mr. Robertson says people might "want to have a little cash on hand, some food, some medicine and some necessary supplies." Around Christmastime, James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family, increased employee bonuses by about $200 to about $500, and suggested that, among other things, the extra cash could go to Y2K preparations. On his radio show, Dr. Dobson has said he puts himself in the "camp of those who think there will be some tough times before we're through with it."

The warnings are more dire on the Internet, where Web sites linking Y2K to the Second Coming are proliferating. "I've never seen anything grow so fast," says Charles Henderson, who studies religious sites for the Internet guide MiningCo.com (miningco.com ). Michael S. Hyatt, associate publisher at the country's biggest religious publishing house, Thomas Nelson Inc., wrote a book called "The Millennium Bug: How to Survive the Coming Chaos," which is now No. 70 on Amazon.com's weekly bestseller list.

The clergy, often untutored in the arcana of technology, find themselves sifting through the news to arrive at an official position on the computer bug. Morris H. Chapman, chief executive officer of the Southern Baptist Convention's executive committee, told Baptist leaders in September to pray on this question: "If significant disruptions occur, will I be prepared to provide for my family?"

Of course, there are many Christians -- from the most traditional Protestants to the most fundamentalist evangelicals -- who refuse to listen to the alarms. The Rev. Ron Sisk, who leads a Baptist congregation in Louisville, Ky., calls the link between Y2K and the end of time "hooey." The Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal denomination known for speaking in tongues, released a statement in October advising constituents "not to engage in activities such as hoarding food, withdrawing money from banks, believing doomsday scenarios."

But among today's visible and media-savvy evangelical leaders, practically no one preaches a take-it-easy approach. When a few parishioners began to ask the Rev. Larry Heenan, pastor of Spring Valley church here, to buy generators and cots to prepare for Y2K, there was only one person he could think of to calm the masses: Mr. Hewitt.

And about those water purification tablets...

Indeed, an entire industry devoted to helping Christians prepare for Y2K has blossomed. The Joseph Project, a Web site (www.josephproject2000.org ) selling freeze-dried soups and vegetables in bulk, recently advised shoppers that "Y2K awareness has caused a mountain of orders"; a 20-pound bag of carrots costs $115, including shipping. Many Christian Y2K books are cropping up, such as "The Millennium Meltdown" by Grant Jeffrey and "Y2K=666?" by Noah Hutchings.

On his Web site (www.familyinteractive.net/millennium.html ), Mr. Hyatt, author of "The Millennium Bug," sells the "Countdown to Chaos Protection Kit," a six-audiotape set plus an accompanying handbook, complete with "recommendations, checklists, and the essential resources and supplies you'll need to survive this looming crisis"-for $89. And in Sacramento, Calif., Derek Packard came out of retirement to produce "National Y2K Readiness Seminars," a package of three live satellite broadcasts for churches for $1,495 with a satellite dish, or $995 for churches that already own one. (Mr. Packard says he has applied for nonprofit status.)

There have always been a apocalyptic element in Christianity, dating back to the earliest days of the church. Even putting aside Revelations, it is an essential part of the religion, particularly with the evangelical denominations I grew up around.

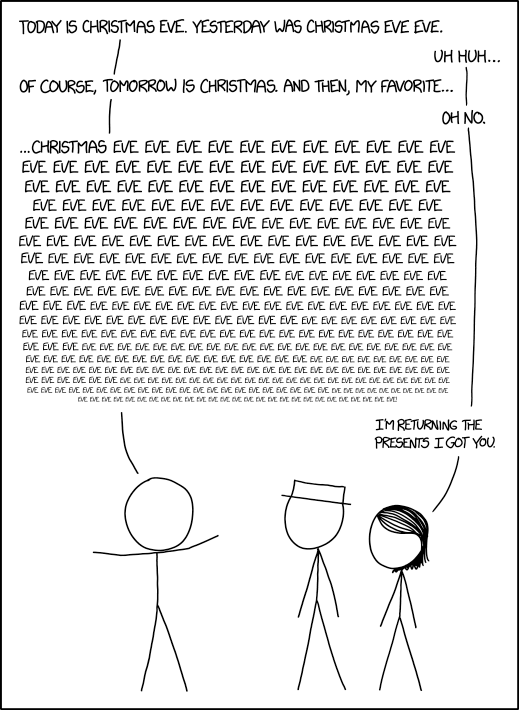

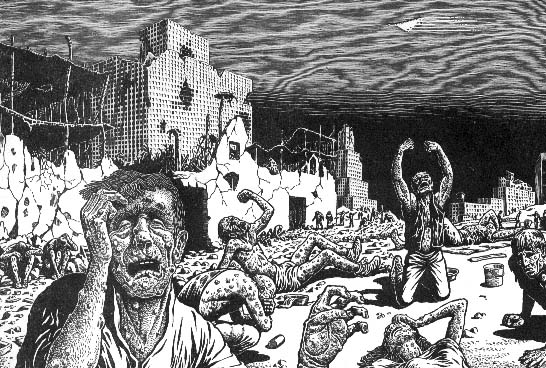

I say "around" because, as a lapsed Presbyterian, my childhood memories of church have none of

this

and lots of this

But for many friends and classmates, end times was something that was a part of their religion. I do want to emphasis that it usually was not a large part. For most, it was far-away and half-believed, mainly background noise.

I haven't made any kind of serious study of this but sometime in the late Nineties, I started to notice that things had changed. For people naturally inclined to see portents, there seemed to be signs everywhere. There was the end of the millennium. There were news reports of massive systemic collapse. The Nineties also saw the rise of a right-wing media establishment that made extensive use of implicitly apocalyptic language and imagery (often hinting at impending race and class wars). The relationship between evangelical Christianity and conservative media is quite complex and deserves a few posts of its own, but for now, let's just say that watching Fox News and listening to Rush Limbaugh didn't help.

Though the distinction may not show up that clearly on surveys and other social science tools, there is a huge difference between saying you believe the end of the world is coming and saying that the end of the world is coming next Thursday. In the late Nineties, for the first time, so far as I know, a large segment of mainstream American churches started treating the events described very vaguely in the book of revelations as something specific and immediate. The Y2K bug was expected to trigger a series of cataclysms that, for those who knew what to look for, would clearly fit with biblical prophecies. Up until the late 90s, even most hard-core fundamentalist had only kind of sort of believe this because "it's in the Bible so you have to. "Now it was something real enough to send you to the Bible store for survival gear.

Once again, I'm no expert but I do know that there is a great deal of literature out there on the subject of into the world Colts, going all the way back to When Prophecies Fail.

It would be great if we could get an expert on cognitive dissonance to weigh in here, but strictly from a layman's perspective, it certainly seems reasonable to conclude that this widespread belief in the Y2K catastrophe has continued to have an effect . People on the far right are clearly predisposed to see the coming upheaval. Tune in to Glenn Beck or watch a Ron Paul infomercial and the message is painfully obvious. A Fox News segment on Muslims or the rise of minorities and the lower classes is only slightly more subtle.

There is considerable overlap between in the world believers and conspiracy theorists. This overlap can partially be explained by a similar mentality. Both groups are constantly on the lookout for patterns and both have the ability to accept as evidence what would seem to be contradictory positions. Fiat money, secular one world government, sharia law , and a bilingual America may not seem to have much in common to you, but to those with the proper mindset, they all tell fundamentally the same story.

.jpg)