To understand the 21st century narrative around technology and progress, you need to go back to two eras of extraordinary advances, the late 19th/early 20th centuries and the postwar era. Virtually all of the frameworks, assumptions, imagery, language, and iconography we use to discuss and think about the future can be traced back to these two periods.

The essential popularizer of science in the latter era was Willy Ley. In terms of influence and popularity, it is difficult to think of a comparable figure. Carl Sagan and Neil Degrasse Tyson hold somewhat analogous positions, but neither can claim anywhere near the impact. When you add in Ley's close association with Werner von Braun, it is entirely reasonable to use his books as indicators of what serious people in the field of aerospace were thinking at the time. The excerpt below comes with a 1949 copyright and gives us an excellent idea of what seemed feasible 70 years ago.

There is a lot to digest here, but I want to highlight two points in particular.

First is the widespread assumption at the time that atomic energy would play a comparable role in the remainder of the 20th century to that of hydrocarbons in the previous century and a half, certainly for power generation and large-scale transportation. Keep in mind that it took a mere decade to go from Hiroshima to the launch of the Nautilus and there was serious research (including limited prototypes) into nuclear powered aircraft. Even if fusion reactors remained out of reach, a world where all large vehicles were powered by the atom seemed, if anything, likely.

Second, check out Ley's description of the less sophisticated, non-atomic option and compare it to the actual approach taken by the Apollo program 20 years later.

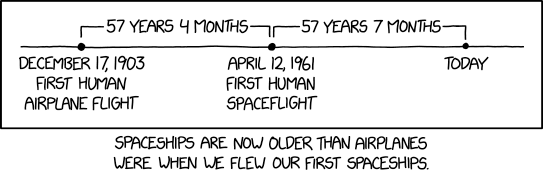

I think we have reversed the symbolic meaning of a Manhattan project and a moonshot. The former has come to mean a large, focus, and dedicated commitment to rapidly addressing a challenging but solvable problem. The second has come to mean trying to do something so fantastic it seems impossible. The reality was largely the opposite. Building an atomic bomb was an incredible goal that required significant advances in our understanding of the underlying scientific principles. Getting to the moon was mainly a question of committing ourselves to spending a nontrivial chunk of our GDP on an undertaking that was hugely ambitious in terms of scale but which relied on technology that was already well-established by the beginning of the Sixties.

________________________________________________

The conquest of space by Willy Ley 1949

Page 48.

In general, however, the moon messenger [and unmanned test rocket designed to crash land on the moon – – MP] is close enough to present technological accomplishments so that its design and construction are possible without any major inventions. Its realization is essentially a question of hard work and money.

The manned moonship is a different story. The performance expected of it is, naturally, that it take off from the earth, go to the moon, land, takeoff from the moon, and return to earth. And that, considering known chemical fuels and customary design and construction methods, is beyond our present ability. But while the moon ship can make a round-trip is unattainable with chemical fuels, a moon ship which can land on the moon with a fuel supply insufficient for the return is a remote possibility. The point here is that one more attention of the step principle is possible three ships which landed might have enough fuel left among them for one to make the return trip.

This, of course, involves great risk, since the failure of one ship would doom them all. Probably the manned moon ship will have to be postponed until there is an orbital nation. Take off from the station, instead of from the ground, would require only an additional 2 mi./s, so that the total works out to about 7 mi./s, instead of the 12 mi./s mentioned on page 44.

Then, of course, there is the possibility of using atomic energy. If some 15 years ago, a skeptical audience had been polled as to which of the two "impossibilities" – – moon ship and large scale controlled-release of atomic energy – – they considered less fantastic, the poll would probably have been 100% in favor of the moon ship. As history turned out, atomic energy came first, and it is now permissible to speculate whether the one may not be the key to the other.

So far, unfortunately, we only know that elements like uranium, plutonium, etc., contain enough energy for the job. We also know that this energy is not completely accessible, that it can be released. He can't even be released in two ways, either fast in the form of a superexplosion, or slowly in a so-called "pile" where the energy appears mainly as he. But we don't know how to apply these phenomena to rocket propulsion. Obviously the fissionable matter should not form the exhaust; there should be an additional reactant, a substance which is thrown out: plain water, perhaps, which would appear as skiing, possibly even split up into its component atoms of hydrogen and oxygen, or perhaps peroxide.

The "how" is still to be discovered, but it will probably be based on the principle of using eight fissionable element's energy for the ejection of a relatively inert reactant. It may be that, when that problem has been solved, we will find a parallel to the problem of pumps in an ordinary liquid fuel rocket. When liquid fuel rockets were still small – – that was only about 17 years ago and I remember the vividly – – the fuels were forced into the rocket motor by pressurizing the whole fuel tank. But everybody knew then that this would not do for all time to come. The tank that had to stand the feeding pressure had to have strong walls. Consequently it was heavy. Consequently the mass ratio could not be I. The idea then was that the tank be only strong enough to hold the fuels, in the matter of the gasoline tank of a car or truck or an airplane, and that the feeding pressure should be furnished by a pop. Of course the pump had to weigh less than the saving in tank wall weight which they brought about. Obviously there was a minimum size and weight for a good home, and if that minimum weight was rather large, a rocket with pumps would have to be a big rocket.

It happened just that way. Efficient pumps were large and heavy and the rocket with pumps was the 46 foot the two. The "atomic motor" for rockets may also turn out to be large, the smallest really reliable and efficient model may be a compact little 7 ton unit. This would make for a large rocket – – but the size of a vehicle is no obstacle if you have the power to move it. Whatever the exhaust velocity, it will be high – – an expectation of 5 mi./s may be conservative. With such an exhaust velocity the mass ratio of the moon ship would be 11:1; with an exhaust velocity of 10 mi./s the mass ratio would drop .3:1!

The moon ship shown in the paintings of the second illustration section is based on the assumption of a mass ratio of this order of magnitude, which in turn is based on the assumption of an atomic rocket motor.

Naturally there would be some trouble with radioactivity in an atomic propelled rocket. But that is not quite as hard to handle as the radioactivity which would accompany atomic energy propulsion under different circumstances. A seagoing vessel propelled by time and energy could probably be built right now. It would operate by means of an atomic pile running at the center high enough to burden and water steam. The steam would drive a turbine, which would be coupled to the ships propeller. While all this mechanism would be reasonably small and light as ship engines go, it would have to be encased in many tons of concrete to shield the ships company against the radiation that would escape from the pile and from the water and the skiing the coolant. For a spaceship, no all-around shielding needed, only a single layer, separating the pilot's or crew's cabin in the nose from the rest of the ship. On the ground a ship which had grown "hot" through service would be placed inside a shielding structure, something like a massive concrete walls, open at the top. That would provide complete shielding or the public, but a shielding that the ship would not have to carry.

The problem that may be more difficult to handle is that of the radioactivity of the exhaust. A mood ship taking off with Lee behind a radioactive patch, caused by the ground/. Most likely that radioactivity would not last very long, but it would be a temporary danger spot. Obviously moon ship for some time to come will begin their journeys from desolate places. Of course they might take off by means of booster units producing nothing more dangerous in their exhaust them water vapor, carbon dioxide, and maybe a sulfurous smell.