Trying to predict the future is a discouraging and hazardous occupation because the prophet invariably falls between two stools. If his predictions sound at all reasonable, you can be quite sure that within 20 or, at most, 50 years, the progress of science and technology has made him seem ridiculously conservative. On the other hand, if by some miracle a prophet could describe the future exactly as it was going to take place, his predictions would sound so absurd, so far-fetched, that everybody would laugh him to scorn. This has proved to be true in the past, and it will inevitably be true, even more so, of the century to come.

The only thing we can be sure of about the future is that it will be absolutely fantastic.

So, if what I say to you now seems to be very reasonable, then I'll have failed completely. Only if what I tell you appears absolutely unbelievable, have we any chance of visualizing the future as it really will happen.

I can't quite recommend Paul Collins' recent New Yorker piece about the book Toward the Year 2018. Collins doesn't bring a lot of fresh insight to the subject (if you want a deeper understanding of how people in the past looked at what was formerly the future, stick with Gizmodo's Paleofuture), but it did turn me on to what appears to be a fascinating book (I'll let you know in a few days) which provides a great jumping off point for a discussion I've been meaning to have for a while.

If you wanted to hear the future in late May, 1968, you might have gone to Abbey Road to hear the Beatles record a new song of John Lennon’s—something called “Revolution.” Or you could have gone to the decidedly less fab midtown Hilton in Manhattan, where a thousand “leaders and future leaders,” ranging from the economist John Kenneth Galbraith to the peace activist Arthur Waskow, were invited to a conference by the Foreign Policy Association. For its fiftieth anniversary, the F.P.A. scheduled a three-day gathering of experts, asking them to gaze fifty years ahead. An accompanying book shared the conference’s far-off title: “Toward the Year 2018.”

…

“MORE AMAZING THAN SCIENCE FICTION,” proclaims the cover, with jacket copy envisioning how “on a summer day in the year 2018, the three-dimensional television screen in your living room” flashes news of “anti-gravity belts,” “a man-made hurricane, launched at an enemy fleet, [that] devastates a neutral country,” and a “citizen’s pocket computer” that averts an air crash. “Will our children in 2018 still be wrestling,” it asks, “with racial problems, economic depressions, other Vietnams?”

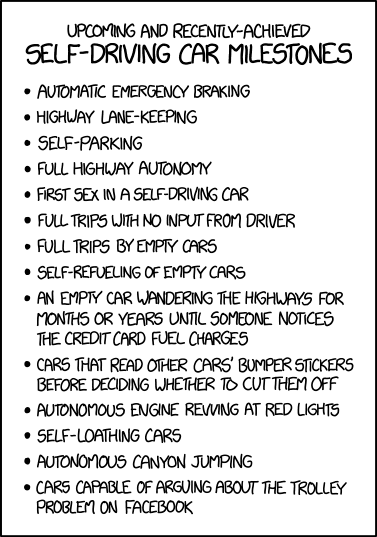

Much of “Toward the Year 2018” might as well be science fiction today. With fourteen contributors, ranging from the weapons theorist Herman Kahn to the I.B.M. automation director Charles DeCarlo, penning essays on everything from “Space” to “Behavioral Technologies,” it’s not hard to find wild misses. The Stanford wonk Charles Scarlott predicts, exactly incorrectly, that nuclear breeder reactors will move to the fore of U.S. energy production while natural gas fades. (He concedes that natural gas might make a comeback—through atom-bomb-powered fracking.) The M.I.T. professor Ithiel de Sola Pool foresees an era of outright control of economies by nations—“They will select their levels of employment, of industrialization, of increase in GNP”—and then, for good measure, predicts “a massive loosening of inhibitions on all human impulses save that toward violence.” From the influential meteorologist Thomas F. Malone, we get the intriguing forecast of “the suppression of lightning”—most likely, he figures, “by the late 1980s.”

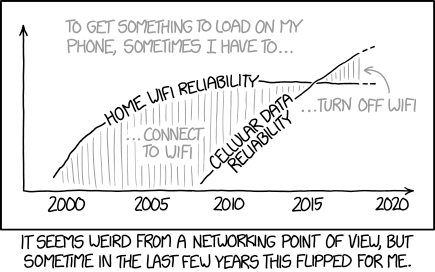

But for every amusingly wrong prediction, there’s one unnervingly close to the mark. It’s the same Thomas Malone who, amid predictions of weaponized hurricanes, wonders aloud whether “large-scale climate modification will be effected inadvertently” from rising levels of carbon dioxide. Such global warming, he predicts, might require the creation of an international climate body with “policing powers”—an undertaking, he adds, heartbreakingly, that should be “as nonpolitical as possible.” Gordon F. MacDonald, a fellow early advocate on climate change, writes a chapter on space that largely shrugs at manned interplanetary travel—a near-heresy in 1968—by cannily observing that while the Apollo missions would soon exhaust their political usefulness, weather and communications satellites would not. “A global communication system . . . would permit the use of giant computer complexes,” he adds, noting the revolutionary potential of a data bank that “could be queried at any time.”

[Though it's a bit off-topic, I have to take a moment to push back against the "near-heresy" comment. Though most people probably assumed manned space exploration would have more of a future after '68, and it certainly would've gone farther had LBJ run for and won a second term (Johnson had been space exploration's biggest champion dating back to his days in the Senate), but the program had always been controversial. "Can't we find better ways to spend that money here on earth?" was a common refrain from both the left and the right.]

As you go through the predictions listed here, you'll notice that they range from the reasonably accurate to the wildly overoptimistic or, perhaps overly pessimistic, depending on your feelings toward weaponized hurricanes (let's just go with ambitious). This matches up fairly closely to what you find in Arthur C Clarke's video essay of a few years earlier, parts that seem prescient while others come off as something from that months issue of Galaxy Magazine.

It's important to step back and remember that it didn't used to be like that. If you had gone back 20, 50, one hundred years, and asked experts to predict what was coming and how soon we get here, you almost certainly would have gotten many answers that seriously underestimated upcoming technological developments. If anything, the overly conservative would probably have outweighed the overly ambitious.

The 60s seemed to be the point when our expectations started exceeding our future. I have some theories as to why Clarke's advice for prognostication stopped working, but they'll have to wait till another post.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)