(Or at least spread the blame around)

I am, for obvious reasons, reluctant to challenge Andrew on questions about polling and political science, but over the past few years, I've spent an unhealthy amount of time studying and commenting on the coverage of elections which leads me to push back on a number of points in his recent post "No, the polls did not predict “a Republican tsunami” in 2022." [For still another take, check out Kaiser's reaction.]

We'll just set the Wayback Machine to 2015...

Though it's a bit off the main topic both for his post and this one, let's start with this:

"In the 2016 primaries, the polls were right about Trump having a bi[g] lead over his opponents; it was the pundits who were wrong."

No one hates pundits more than I do, but if you go back and review the coverage, you'll see that the even-at-the-time embarrassing push to deny that Trump was the front-runner came primarily not from pundits but from data journalists. If you're looking for flawed, narrative-serving "Trump won't get the nomination" arguments in the NYT archives, you'll find far more from Nate Cohn than from David Brooks.

If you're a real glutton for punishment, go back and read the posts we did on the subject back in 2015. One on 538, and two on Nate Cohn. Silver later went back and made a real effort to acknowledge and address his mistakes. As far as I know, Cohn (who was a much more serious offender) never did.

There are polls, then there are polls.

The main focus of Andrew's post is this quote from a London Review of Books article by Adam Shatz.

The polls, unreliable as ever (this was one thing Trump got right), told us that high inflation and anxiety about crime were going to provoke a Republican tsunami.

To which Andrew replied:

But that’s wrong! First, the polls are generally not “unreliable,” and it’s particularly wrong to cite Trump here (more on this below). Second, no, the polls in 2022 did not “tell us” there would be “a Republican tsunami.” The pundits in 2022 were off, but the polls did just fine.

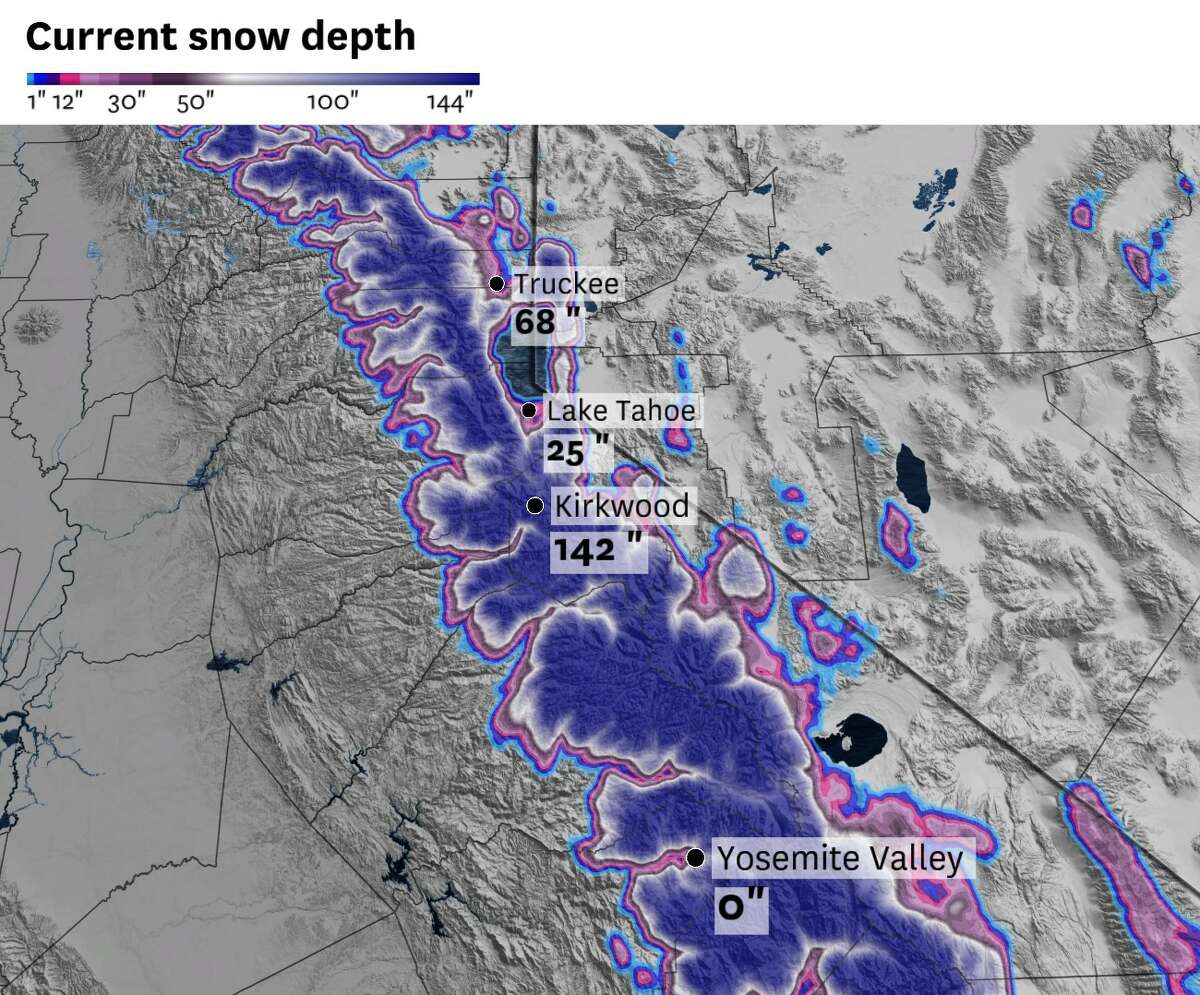

For example, here are the poll-based forecasts for the Senate and House of Representatives from the Economist magazine (they should have some copies floating around in the LRB offices, right):

The actual outcomes (Republicans ended up with 49 seats in the Senate and 222 in the House) are close to the point forecasts and well within the forecast intervals.

The polls are not magic—they won’t tell you who will win every close race, and they can be off by a lot on occasion, but (a) they’re pretty good on aggregate, and (b) no, they did not predict a Republican tsunami.

I

found Shatz's piece painfully conventional and largely free of

insight (but remember, I hate pundits). That out of the way, the example

Andrew gives doesn't address what Shatz actually said. This is going to

be a fine point but an important one. Just so there's no possibility of missing context, here

are the three paragraphs where Shatz talks about the polls. (Only the

first two are relevant to this conversation; I'm including the third

just for the sake of completeness.)

I spent much of the night brooding on the impending birth of the United

States of QAnon. A Republican sweep seemed inevitable. The president’s

party usually gets clobbered in midterm elections. Despite all Biden’s

achievements – high employment, investment in infrastructure, a historic

climate change bill – his approval ratings were in the low forties, as

if the only things Americans could remember about him were his

stammering delivery and the chaos of the (otherwise popular) withdrawal

from Afghanistan. The polls, unreliable as ever (this was one thing

Trump got right), told us that high inflation and anxiety about crime

were going to provoke a Republican tsunami. Afterwards, Republican

legislators and election-denying secretaries of state (the chief

election officials in US elections) would join forces to

prevent the Democrats from winning in 2024 – or ever again. The country

appeared to be careening towards constitutional crisis, and the other

side had all the guns.

...

All of this led Biden to give one of the most sombre and unflinching

speeches delivered in recent memory by an American leader. ‘Lies of

conspiracy and malice,’ he said on 3 November, had produced ‘a cycle of

anger, hate, vitriol, and even violence’. The survival of American

democracy, he continued, was now ‘the biggest of questions ...

You can’t love your country only when you win.’ Much of his rhetoric

sounded old-fogeyish (‘a struggle for the very soul of America itself’),

but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t right about the threat. His political

calculations were also sound. According to the polls, inflation and

crime were the major issues for most Americans, not abortion or

democracy. Yet Biden’s insistence that ‘democracy is on the ballot for

us all’ resonated with many voters who were fed up with the persistence

of minority rule, the furies (and the outsized power) of the far right

and the normalisation of violence by political pundits and elected

representatives. Whatever Biden’s approval ratings, his warnings in this

speech may have helped to set the stage for the Democrats’ strong

showing; so, too, did his success in restoring a modicum of civility to

American political life.

...

Why were supporters of the Democrats –

including seasoned election-watchers – so easily persuaded by Republican

triumphalism? The polls were one reason, of course. But susceptibility

to Republican hype is more directly a result of the Trump years. There

is every reason to fear that Trump, or rather Trumpism, might return.

It’s easy to mock MSNBC-watching liberals who rapidly

resort to analogies with Germany in the 1930s (especially when analogies

with episodes in American history, such as Reconstruction and the

McCarthy era, are closer to hand and more illuminating). But there is

little doubt that the United States has become more vulnerable to

authoritarian challenges thanks to the deterioration of its democracy

over the last two decades. The reasons for this decline are many but

include the absence of limits on campaign finance and the overwhelming

influence of corporate money, the right-wing assault on black

enfranchisement and the descent of some quarters of red America into

conspiratorial culture-war fanaticism.

In

both relevant paragraphs, Shatz is talking about opinion/attitude polls

while Andrew counters with results derived largely (entirely?) from

electoral polls. This is an obvious mismatch but it also raises some

subtle but far more significant points, but before we get to that, there are a few things we need to get out of the way.

When you only look at good polls, the polls are good

In the final days of the election, observers such as Rosenberg (who, like his associate Tom Bonier, came out of 2022 looking really smart) were raising the alarm about a wave of junk polls designed to juice the red tsunami narrative.

Conscientious poll aggregators either gave the junk little weight or ignored it entirely, so the damage on that side was minimal, but when we make blanket statements about "the polls," we can't simply pretend these don't exist.

Elsewhere in the Economist

At the peak of the campaign, a couple of analyses from the Economist and the NYT rattled everyone's cages.

More 2020 Poll Forebodings

By Josh Marshall

|

September 12, 2022 8:52 p.m.

Over the last couple weeks we’ve seen write-ups pointing to the

possibility or probability that polls in 2022 will underestimate

Republican strength just as they did in 2020. Now Nate Cohn has one in The New York Times.

Cohn’s analysis is particularly interesting to me since he’s been a

fairly consistent skeptic of polls in recent cycles in terms of their

ability to accurately gauge the strength of the Trump coalition. G.

Elliott Morris had a similar write-up in The Economist last week. Philip Bump kicked the tires on Morris’s claims in the Post.

While they break down the numbers, the gist is pretty straight-forward:

If you take the polling error from 2016 and 2020 and plug it into our

current polls you go from Dems being in a strong position for holding

and even expanding their senate majority to more like a 50-50 odds of

holding the chamber at all. On the House, a GOP majority and maybe a

significant one is basically a given.

So what to make of all this? On the specifics these analyses are right. And that is sobering. No question about it. So how likely are we to see a repeat of 2020? I wish I knew. The one thing that stands out to me about both these analyses is that they leave out 2018. That was obviously a good year for Democrats, though more in the House than in the Senate. It was also a midterm. So there’s a decent argument that it’s a more like comparison to this year’s midterm. Morris notes that even though 2018 was a good year for Democrats it had similar polling biases to 2016. When I asked Morris why he excluded 2018, given it’s the best year recently for Democrats, he told me that the point of his experiment wasn’t to predict the 2022 outcome but rather to show a worst case scenario for Democrats. I think that’s a reasonable answer and I suspect it’s Cohn’s too.

Morris's statements to Marshall are more cautious and qualified than his piece in the Economist (where the phrase "worst case scenario" does not appear, which in turn was more cautious and qualified than were his tweets on the subject. None of this is to suggest that there was anything inaccurate or irresponsible about Morris's analysis, but it's another reminder that the pundits in large part got the impression that we were looking at a red wave because they were reading data journalism in places like the Economist and the NYT.

Downplaying Dobbs

A number of analyses (most notably this one from Nate Cohn at the NYT) suggested that the impact of abortion would be less than most people were expecting.

Polling suggests an overturning of Roe v. Wade might not carry political consequences in states that would be likeliest to put in restrictions.

Cohn did give himself some wiggle room but on the whole it was a bad analysis as we pointed out at the

time. By way of comparison, it would have made more sense to do an analysis showing how little usable data we have on the political impact of an overheated US economy (high inflation/high employment) as compared with stagflation. I don't recall anything like that getting any attention.

But these are minor issues compared with the problems with how pundits, data journalists, and in some cases political scientists talk about polls.

Polls do not predict. That's the problem.

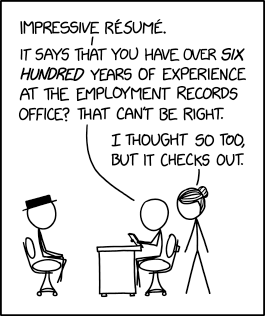

Polls (at least electoral polls) look like predictions. You can often treat them as predictions, using them as the sole input for very simple models, but the polls themselves are not making any predictions; they are just tools for measuring beliefs and attitudes, and the ways we need to think about them (and about how they can go wrong) are entirely different than the ways we need to think about predictive models.

Specifically in this case, we need to think about what did and didn't go into the models that made the predictions. As far as I can tell the big inputs were electoral polls, attitude polls, presidential approval polls, the economy, and recent/historic voting patterns. These are all standard and quite reasonable choices when trying to predict elections, and every one of them was holding up a big "RED TSUNAMI" sign.

The absolute certainty that this was going to be a disastrous year for the Democrats entrenched itself early in the election and it did not originate with the pundits; they got it from sources like the Upshot, and you can't really blame them for reading their own papers.

[Obviously, I can blame them -- as mentioned before, I hate pundits -- but in this case we need to take a hard look at the "serious" people, not just the op-ed dwellers.]

It's not like no one saw that there were potential problems with the models. A number of people (including Joseph and I) argued we were so far out of the range of observed data that nothing model based could be trusted. There were also analysts looking into the data who came up with a very different take, most notably, Tom Bonier who staked out a very lonely position based on voter registration numbers, special elections turnout, and early voting data. Ironically, his stuff showed up in the NYT as guest editorials, meaning that the opinion section of the paper actually had better writing about data than what we saw in the data journalism section.

https://twitter.com/MarkPalko1/status/1650233537659031552?s=20