A few days ago, we did a post about an absolute train wreck (spaceship wreck? Hyperloop wreck?) of a book review/essay in The New Yorker that somehow managed to connect the late–19th-century interest in Martian life with the press’s handling of the Epstein files — all while including a stunningly ill-informed take on Elon Musk.

As bad as the piece was, one line managed to stand out from the rest in terms of sheer awfulness:

"Musk, of course, named his car company after Tesla"

Elon Musk has spent the past 20 years trying to retcon himself as the founder of Tesla, but the facts are a matter of historical record: Tesla was named by the two real engineers who founded the company six months before Musk had any involvement whatsoever. This is not a point of dispute — even Musk apologists will concede it if directly challenged. Even the most cursory research would have uncovered this mistake. Nonetheless, it made it past the writer, the editor, and the magazine's vaunted fact-checking department.

Longtime readers will know that this isn’t the first time we’ve caught the New Yorker being sloppy with details and slow with corrections.

For years now, various experts on Buster Keaton and/or the legendary comic strip Pogo (“We have met the enemy and he is us”) — including the Keaton biographer who was their primary source — have been trying to get The New Yorker to correct its claim that Walt Kelly, the cartoonist, was the brother-in-law of the great filmmaker. (It turns out there was more than one Walt Kelly.)

Years before that, we fact-checked an article on the music of 1960s spy shows that was so riddled with errors it took an entire post — plus a post script — to catch them all, including the misattribution of some of the most famous pieces by legends like Jerry Goldsmith. As with the other two examples, these mistakes went uncorrected for years and, as far as I know, are still there.

Now let’s talk about an experience I had recently with Wikipedia.

A couple of weeks ago, I finished Nothing to Lose, one of the Jack Reacher novels (weaker than Echo Burning as a mystery, generally stronger as a thriller, in case you’re considering picking up a copy). I’ve gotten in the habit of checking Wikipedia after finishing a book or movie — sometimes for interesting trivia, sometimes for follow-up suggestions.

In this case, what was supposed to be a quick glance at the plot summary turned into multiple rereads as I tried to figure out what the hell they were talking about.

It wasn’t that the description was incoherent; it just seemed to be about an entirely different book. The locations and character names were the same, and the first paragraph sort of matched the opening 50 pages. After that, it was like the writer had lost their copy and decided to make up their own version from memory.

If I had to guess, I’d say it was done by something like ChatGPT — partly because of the way it read, and partly because I can’t imagine why anyone would put that much time into writing a plot summary for a book they clearly hadn’t read.

I’m not registered to edit Wikipedia, so I made a fairly detailed list of the factual errors — enough to show this wasn’t just a case of getting a few details wrong — and posted it to the talk page. The next day, I checked back and found the old summary had already been replaced with a much more accurate capsule version from Sherryl Connelly of the New York Daily News.

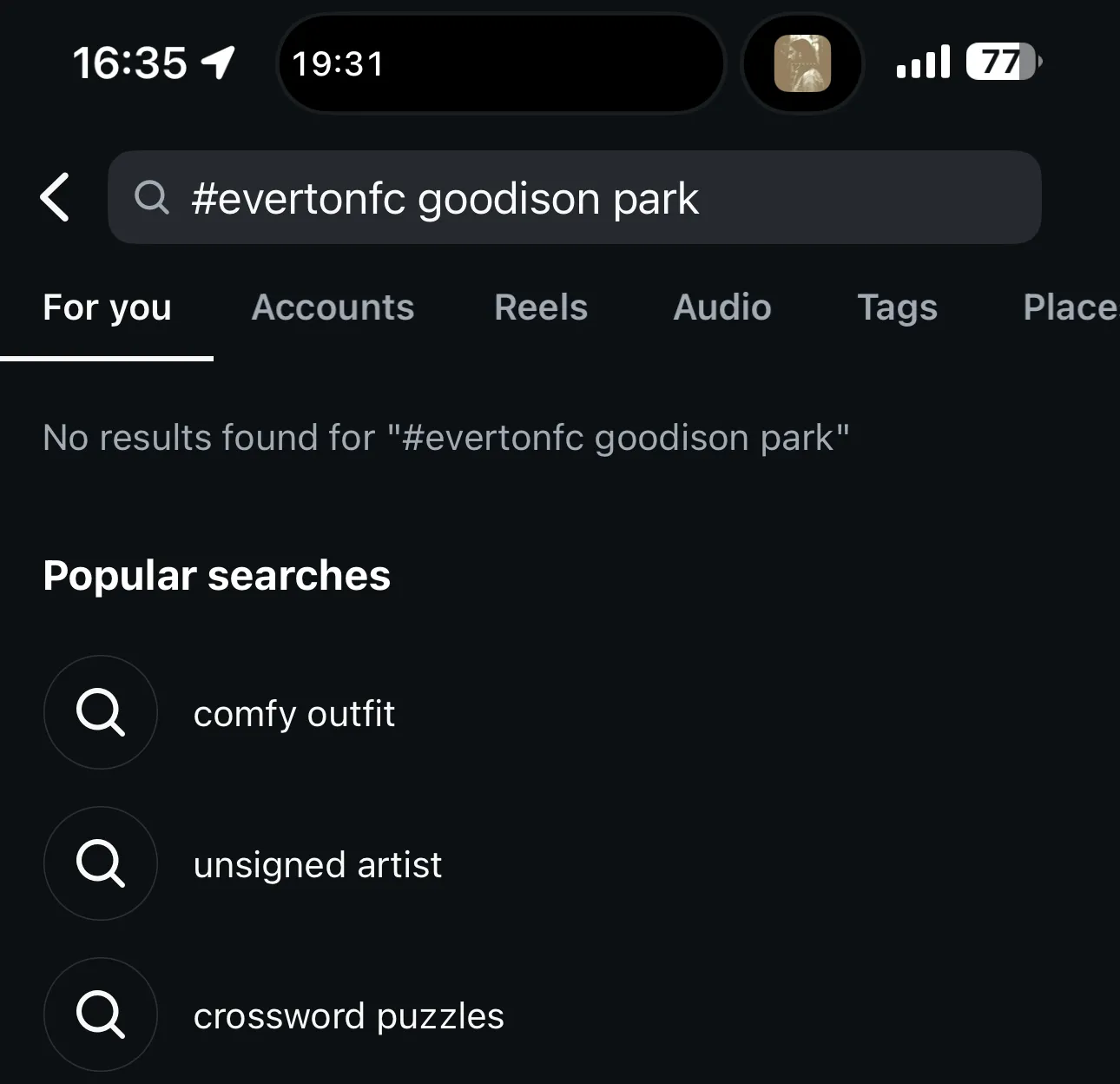

Then I clicked on the talk page and found the following:

The timestamp showed that, despite this being a very minor Wikipedia page, the editors had addressed the problem and removed the original contributor’s edits from this and several other pages — all within less than five hours.

Next time you see journalists writing long, pretentious think pieces about why the public has lost faith in them, feel free to send them a copy of this post.