... And it feels like nothing has changed.

Wishful Analytics

As mentioned previously,

Donald Trump's campaign has definitely strained the standard

assumptions of political reporting, Though this is an industry wide problem (even Five Thirty Eight hasn't been immune), it is nowhere more severe than at the New York Times.

The trouble is that the New York Times is very much committed to a

style of political analysis that takes the standard narrative almost

to the formal level of a well-made play. The objective is to get to

the preassigned destination with as much craft and wit as possible.

Nate Silver's problems at the NYT generally came from his habit of

following the data to conclusions that made his editors and

colleagues uncomfortable (by raising disturbing questions about the

value of their work).

Cohn's articles on Trump have been an extended study in wishful

analytics, starting with a desired conclusion then trying to dredge

up some numbers to support it. He

really,

really,

really,

really,

really

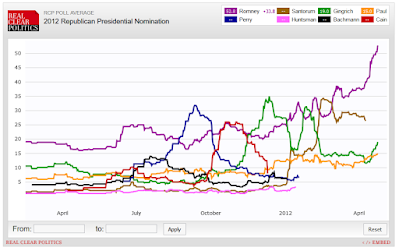

wants to see Trump as another Herman Cain. Other than both being

successful businessmen, the analogy is strained -- Cain was a

little-known figure who surged well into the campaign because the base

was

looking for an alternative to an unacceptable presumptive nominee –

but Cohn brings up the pizza magnate at every opportunity.

In addition to reassuring analogies, Cohn is also inclined to see

comforting inflection points. Here's his

response to the McCain

dust-up.

The Trump Campaign’s Turning Point

Donald Trump’s surge in the polls has followed the classic

pattern of a media-driven surge. Now it will most likely follow the

classic pattern of a party-backed decline.

Mr. Trump’s candidacy probably reached an inflection point on

Saturday after he essentially criticized John McCain for being

captured during the Vietnam War. Republican campaigns and elites

quickly moved to condemn his comments — a shift that will probably

mark the moment when Trump’s candidacy went from boom to bust.

Paul Krugman (like Silver, another NYT writer frequently at odds

with the paper's culture)

dismantled this argument by immediately spotting the key flaw.

What I would argue is key to this situation — and, in particular, key to

understanding how the conventional wisdom on Trump/McCain went so wrong

— is the reality that a lot of people are, in effect, members of a

delusional cult that is impervious to logic and evidence, and has lost

touch with reality.

I am, of course, talking about pundits who prize themselves for their centrism.

...

On one side, they can’t admit the moderation of the Democrats, which is

why you had the spectacle of demands that Obama change course and

support his own policies.

On the other side, they have had to invent an imaginary GOP that bears

little resemblance to the real thing. This means being continually

surprised by the radicalism of the base. It also means a determination

to see various Republicans as Serious, Honest Conservatives — SHCs? —

whom the centrists know, just know, have to exist.

...

But the ur-SHC is John McCain, the Straight-Talking Maverick. Never mind

that he is clearly eager to wage as many wars as possible, that he has

long since abandoned his once-realistic positions on climate change and

immigration, that he tried to put Sarah Palin a heartbeat from the

presidency. McCain the myth is who they see, and keep putting on TV. And

they imagined that everyone else must see him the same way, that

Trump’s sneering at his war record would cause everyone to turn away in

disgust.

But the Republican base isn’t eager to hear from SHCs; it has never put

McCain on a pedestal; and people who like Donald Trump are not exactly

likely to be scared off by his lack of decorum.

Cohn's initial reaction to his failed prediction was to argue that the polls weren't

current enough to show that he was right. When

that position became untenable, he shifted his focus to the next

inflection point:

Mr. Rubio, the senator from Florida, has a good case to be

considered the debate’s top performer. A weaker Mr. Bush probably

benefits Mr. Rubio as much as anyone, and if Mr. Bush raised

questions about whether he would be a great general election

candidate, then Mr. Rubio added yet more reason to believe he could

be a good one. Mr. Rubio still has the challenge of figuring out how

to break through a strong field in a factional party.

...

Mr. Walker won by not losing. In a lot of ways, the moderators’

tough, specific questions played to Mr. Walker’s weakness. He

didn’t have much time to emphasize his fight against unions in

Wisconsin. But he handled several tough questions — on abortion; on

relations with Arab nations; what he would do after terminating the

Iran deal; race; and his employment record — without appearing

flustered or making a mistake. His answers were concise and sharp.

...

Mr. Kasich also advanced his cause. He entered as a largely

unknown candidate outside of Ohio, where he is governor. But he was

backed by a supportive audience, he deftly handled tough questions,

and he had a solid answer on a question about attending same-sex

weddings. His answer might not resonate among many Republicans, but

it will resonate in New Hampshire — the state where he needs to

deny Mr. Bush a path to victory and vault to the top of the pack.

It was Donald Trump, though, who might have had the weakest

performance. No, it may not be the end of his surge. But he

consistently faced pointed questions, didn’t always have

satisfactory answers, endured a fairly hostile crowd and probably

won’t receive as much media attention coming out of the debate as

he did in the weeks before it. If you take the view that he’s

heavily dependent on media coverage, that’s an issue. Whatever

coverage he does get may be fairly negative — probably focusing on

his unwillingness to guarantee support for the Republican nominee.

You might want to reread that last paragraph a couple of times to

get your head around just how wrong it turned out to be. Pay

particular attention to the statements qualified with 'probably' both

here and in the McCain piece. The confidence displayed had nothing to

do with likelihood – all were comically off-base – and had

everything to do with how badly those committed to the standard

narrative wanted the statements to be true.

This attempt to prop up that narrative have become increasing

strained and convoluted, as you can see from the most

recent entry

Yet oddly, the breadth of [Trump's] appeal and his strength reduce

his importance in shaping the outcome of the race.

If Mr. Trump were weaker, or if his support were more narrowly

concentrated in either New Hampshire or Iowa, he would play a bigger

role in shaping the outcome. In that scenario, a non-Trump candidate

might win either Iowa or New Hampshire — and he or she would be in

much better position than the second-place finisher in the state

where Mr. Trump was victorious.

If Mr. Trump were to win both Iowa and New Hampshire, the

second-place finishers would advance as if they were winners.

Assuming that one or both of the second-place finishers were broadly

acceptable, the party would try to coalesce behind one of the two

ahead of the winner-take-all contests on March 15.

In the end, Mr. Trump almost certainly won’t win the Republican

nomination; the rest of the party will consolidate around anyone

else. He can influence the outcome only if his support costs another

candidate more than others. But for now, he seems to be harming all

candidates fairly equally.

First off, notice the odd way that Cohn discusses influence. If I

asked if you would like to “play a bigger role in shaping the

outcome” of something, you would naturally assume I meant would you

like to have more of a say, but that's not at all how the concept of

influence is used in the passage above. Cohn is simply saying that a

world where Trump was behind in one of the first two primaries might

have a different nominee but since Trump wouldn't get to pick who

would beat him, it's not clear why he would care and since there's no

telling who would win in Cohn's alternate reality, it's not clear why

anyone else would care either.

But even if we accept Cohn's framing, we then run into another

fatal flaw. Put in more precise terms, “harming all candidates

fairly equally” means that each candidate's probability of becoming

president would have been the same had Trump not entered the race.

This is almost impossible on at least three levels:

Trump has already produced a serious shift in the discussion,

bringing issues like immigration and Social Security/Medicare to the

foreground while sucking away the oxygen from others. This is certain to help some candidates more than others;

For this and other reasons, the impact on the polls so far has been anything but symmetric;

And even if Trump's support were coming proportionally from each

of the other contenders, that still wouldn't constitute equal harm.

Primaries are complex beasts. We have to take into account

convergence, feedback loops, liquidity, serial correlation, et

cetera. The suggestion that you could remove the first two primaries

from contention without major ramifications is laughably naive.

Finally there's that “only.” Even if Trump isn't the nominee

(and I would certainly call him a long shot), he can still influence

the process as either kingmaker or spoiler.

While Cohn's work on this topic has been terrible, what's

important here is not the failings of one writer but the current

culture of journalism. This is what happens when even the best

publications in the country embrace conventional narratives and

groupthink, adopt self-serving but silly conventions and let their

standards slip.