Joseph may just be trolling me here:

The recent New York Times article on the twilight of the NIMBY was interesting just for the low level of actual good ideas for why new housing is bad. The idea was to build 20 condos on a hill in a neighborhood of detached houses.

While arguments given here certainly do qualify as "low-level", it's just possible that this has less to do with the quality of the potential reasons not to build this particular structure and more to do with the fact that the New York Times has gone all-in for the narrative that blames the housing crisis on hypocritical liberals in expensive neighborhoods, and we know from experience that when this paper invests in a narrative, the staff will do anything to protect that narrative up to and including sacrificing their first born.

In this case, Kirsch may be illogical, hypocritical, and selfish, but she is not wrong. It actually is a horrible idea to put more development in Mill Valley.

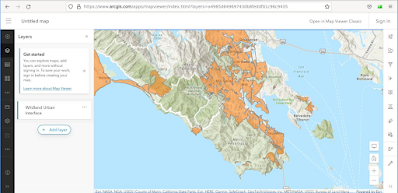

To understand why we don't want more people here and why Conor Dougherty's article can't be taken seriously, we need to start with wildland–urban interfaces (WUIs) "a zone of transition between wilderness (unoccupied land) and land developed by human activity – an area where a built environment meets or intermingles with a natural environment. Human settlements in the WUI are at a greater risk of catastrophic wildfire."

As you can see, Mill Valley construction is problematic from a WUI standpoint.

Nor is history reassuring:

On July 2, 1929, a fire lookout on Mount Tamalpais spotted smoke rising from the railroad grade on the eastern slope. A wildfire, cause unknown to this day, had sparked on the mountain, flames blowing downhill toward Mill Valley below. Though the Great Mill Valley Fire covered a relatively small footprint, it was disproportionately destructive, burning for three days and incinerating more than 100 homes.

Sixteen years later, in September 1945, another major fire stormed through the Mount Tamalpais watershed. Dry weather and strong winds converted a pair of small brush fires into an inferno that burned more than 20,000 acres, from Lagunitas to the Bolinas Lagoon. While there hasn’t been a major fire on Mount Tam in the 74 years since, between 1881 and 1945 the area burned five times.

“Everyone thinks about that,” says Shaun Horne, Natural Resources Program Manager for the Marin Municipal Water District. Without a significant fire in decades, he says, and with the encroachment of invasive plant species, “There’s more potential fuel. It’s a high-hazard environment for wildfire.”

Encouraging development in WUIs is generally a bad idea for a number of reasons. It puts people in harm's way. The smoke from burning buildings is much nastier than the smoke regular forest fires (especially concerning given Mill Valley's location). Most important though is the way that moving ever more people into these areas makes the necessary political calculus all but impossible.

Arguably the biggest crisis facing California at the moment is megafires. The only way to address this crisis is by aggressively promoting the good fires which we have been suppressing for over a century (unlike the native Americans who were here first). Good fires bring with them risks and those risks are primarily focused on places like Mill Valley.

Loads of other issues with this article, too many for a post. Maybe I'll come back to it, or maybe I'll point you to some of the posts I've done on the subject in the past, all of which point to the conclusion that you should never listen to the New York Times' analysis of the California housing crisis (or any other California story).

Remember, LAT > NYT.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2021

Yes, YIMBYs can be worse than NIMBYs -- the opening round of the West Coast Stat Views cage match

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2021

Yes, YIMBYs can be worse than NIMBYs Part II -- Peeing in the River

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2021

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2021

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2021

Did the NIMBYs of San Francisco and Santa Monica improve the California housing crisis?

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021

A primer for New Yorkers who want to explain California housing to Californians

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2021

A couple of curious things about Fresno

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2021

Does building where the prices are highest always reduce average commute times?

MONDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2021

Either this is interesting or I'm doing something wrong

Tuesday, December 21, 2021

The NYT weighs in again on California housing and it goes even worse than expected