Also ran this one in the food blog.

First off, let's look at some numbers.

[From Wikipedia]

National chains

Albertsons LLC - 2,400 stores; besides the parent company, some stores are operated under the banners: Acme Markets, Carrs, Jewel-Osco, Lucky, Pavilions, Randalls and Tom Thumb, Safeway Inc., Shaw's and Star Market, United Supermarkets and Market Street, and Vons

Aldi - 1,401 stores;

Costco - approximately 500 warehouse stores in the USA, plus 200 elsewhere

Ahold Delhaize - 2265 stores under the following brands.

Food Lion (1098 stores in Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia)

Hannaford (188 stores in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont)

Giant-Carlisle (197 stores in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia)

Giant-Landover (169 stores in Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia)

Stop & Shop (416 stores in New York Metro: Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, New England: Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island)

Martin's Food Markets (197 stores in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and West Virginia)

Kmart Super Center - 624 stores

Kroger - 2,460 stores; besides the parent company, stores operate under Baker's Supermarkets, City Market, Dillons Supermarkets, Food 4 Less, Foods Co., Fred Meyer (technically a hypermarket), Fry's Food & Drug, Gerbes Super Markets, Harris Teeter, Jay C, King Soopers, Owen's, Pay Less Super Markets, QFC, Ralphs, Roundy's, Ruler Foods, Scott's, and Smith's

Schnucks - 100+ Stores

SpartanNash - operates 167 retail stores in 44 states, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East

SuperValu Inc. - 1,582 stores (691 corporate and 891 franchised stores); the Save-A-Lot name is its most common banner; others are Cub, Farm Fresh, Hornbacher's, Shop 'n Save and Shoppers

SuperTarget - 251 stores

Trader Joe's - 457 stores (as of April 22, 2015)

Walmart - 3522 stores + 699 Neighborhood Markets + 660 Sam's Clubs (as of January 31, 2017)

Whole Foods - 430 stores (as of June 14, 2016)

Add in a ton of local and regional players and it becomes evident that Whole Foods is not that big of a slice.

The distorting effects of aspect dominance

.

Whole foods is not just small in absolute terms; it is almost exclusively focused on a very narrow target market. Upscale, price insensitive, urban foodies credulously immersed in the world of health and culinary trends. By coincidence, this profile matches almost perfectly with the journalists currently reporting the story.

Whole Foods looms large in the lives of the kind of people who write for New York magazine or produced segments for CNN. This inclines them to lend this story an air of importance it does not merit. For example check out Matt Yglesias.

The post-peak problem

Even with its targeted demographic, there is considerable evidence that Whole Foods was already in danger of losing its dominant position. A decade ago, the chain largely had a lock on the organic and exotic market. If you wanted heirloom tomatoes and cage free eggs and pink Himalayan salt and those big bottles of Dr. Bonner's soap that your stoner friends used to read in the bathtub in college, you could either drive around various health-food shops and co-ops or you could go to Whole Foods.

Recently, though, the company has found its one time monopoly under assault from all sides. Old-fashioned retailers like Kroger's and Walmart have greatly expanded their organic and exotic selections. On the opposite front, small, nimble players like Trader Joe's and Sprouts have gone directly after the target market and have done so with far better prices and superior branding. This latter threat has gotten so bad that Whole Foods was forced to launch the Trader Joe's clone 365.

Before Amazon swooped in, the company had been facing one of the ugliest competitive landscapes in the industry.

"But we'll make it up with volume"

I know it seems a mundane point in this age of disruptors and economages, but Wal-Mart (and Krogers and Costco and ...) have mastered the art of selling groceries at a profit. Amazon appears to have gone into the business largely as a kind of loss leader and it's not clear they have any real plans to move beyond that model.

Wal-Mart, on the other hand, just might

This is an interesting idea, with some potentially big implications.

And finally, Jim Cramer predicts the possibility of great things.

There are few things scarier in the world of finance.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

The scariest quote you'll see on antitrust this week

For reasons I'll try to go into later, I'm not all that worried about the antitrust issues with the Amazon-Whole Foods merger, though that might change with new developments. The sale of a Kroger or a Safeway would certainly make me rethink this, as would a real (rather than all-hype) advance in food delivery systems. For now, though, I'm going to be more concerned by pretty much anything that comes out of Comcast, for example.

But when we do hit the next big antitrust case, this story by Gizmodo's Rhett Jones will worry me deeply. [emphasis added]

But when we do hit the next big antitrust case, this story by Gizmodo's Rhett Jones will worry me deeply. [emphasis added]

Makan Delrahim is Trump’s nominee to handle antitrust cases at the Justice Department. He made it through Senate Judiciary Committee hearings this month and should be starting work soon.

According to The Intercept, Delrahim has spent the last decade working in the private sector on merger deals and is considered to be very corporate friendly in such matters. As The New York Times puts it, he flippantly believes that “a monopoly is perfectly legal until it abuses its monopoly power.” For about 12 years, he has worked for the law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, which just happens to be registered to lobby on Amazon’s behalf.

Over at the FTC, Abbott Lipsky is the acting Director of the Bureau of Competition. Whole Foods has hired Lipsky’s former law firm, Latham & Watkins, to manage the proceedings with Amazon.

Monday, June 19, 2017

An alternate model for the rideshare business

One of the problems with hype-driven businesses and next-big-thingism is that it tends to drive investments and strategies in questionable directions. The best model for an industry might not be sufficiently hype-friendly or it might entail lots of small and medium players rather than one for to behemoth that investors can get excited about. (See the previously mentioned Ponzi threshold).

This got me thinking about the ridesharing industry. We have all largely accepted the Uber/Lyft models as the only way to make the industry work: a huge number of employees (or subcontractors if you prefer) working for a big company that takes care of everything except for the car and the driving.

Instead, what if we thought in terms of something more like a franchise model? You have a national company that handles the branding, dispatching, routing, and billing while a middleman handles the inspection, driver recruitment, and dealing with local authorities.

This would insulate the national corporation from many of the labor issues currently besetting the industry. It could very well significantly reduce cost. It could even go a long way toward letting market forces determine where to grow. Rather than letting some corporate bureaucracy determine which region was suitable, the decision would be based on local entrepreneurs willing to put in the work and put up the money.

This got me thinking about the ridesharing industry. We have all largely accepted the Uber/Lyft models as the only way to make the industry work: a huge number of employees (or subcontractors if you prefer) working for a big company that takes care of everything except for the car and the driving.

Instead, what if we thought in terms of something more like a franchise model? You have a national company that handles the branding, dispatching, routing, and billing while a middleman handles the inspection, driver recruitment, and dealing with local authorities.

This would insulate the national corporation from many of the labor issues currently besetting the industry. It could very well significantly reduce cost. It could even go a long way toward letting market forces determine where to grow. Rather than letting some corporate bureaucracy determine which region was suitable, the decision would be based on local entrepreneurs willing to put in the work and put up the money.

Friday, June 16, 2017

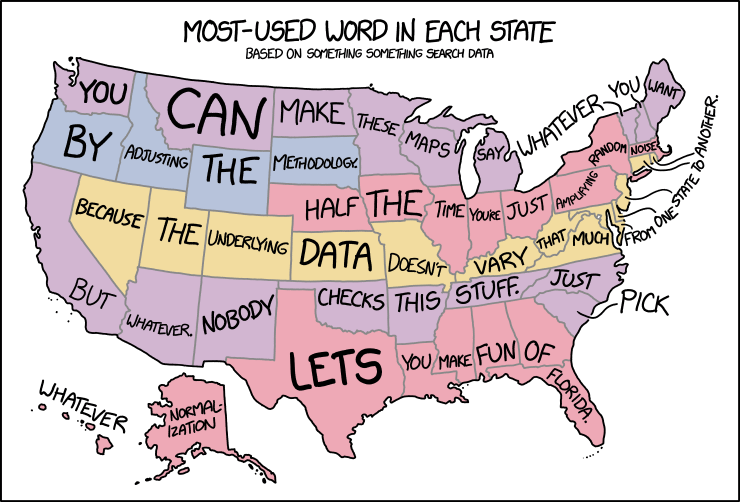

I know you've probably already seen this, but it's too good not to post.

Great work from XKCD. Of all the embarrassing sub genres of statistical pseudoscience journalism, there is not that beats the popularity and the obvious bullshit factor of the every-states-favorite-______. You inevitably start with a sample so inadequate that states like Montana come in with less than a dozen people. Worse still and defying all logic, each state somehow ins up with a different food, singer, or TV show.

The next time you see one of these what-each-state-thinks maps, send the people responsible a copy of this:

Thursday, June 15, 2017

Keeping the Uber thread going

For those joining us late in the show, we've spent this week discussing some of the problems with Uber's current business model and some of the proposals for the future.

Even evil plans require a certain level of competence

Ponzi Thresholds

A follow-up to Mark's post

One of the issues we've brought up more than once is that some of the companies difficulties appear to run so deep that even achieving a monopoly would not be enough to resolve them. Over at LGM, Scott Lemieux has reached a similar conclusion:

Even evil plans require a certain level of competence

Ponzi Thresholds

A follow-up to Mark's post

One of the issues we've brought up more than once is that some of the companies difficulties appear to run so deep that even achieving a monopoly would not be enough to resolve them. Over at LGM, Scott Lemieux has reached a similar conclusion:

But it should be obvious that the Standard Oil model won’t work. There are two fundamental problems facing Uber’s potential profitability:

The inherent costs of entry are low

Demand for cab service is highly elastic

The circle just can’t be squared. The reason it takes a lot of venture capital to compete with Uber is because it’s massively subsidizing riders and drivers. But if you assume that Uber can charge market rates and still make a profit, then it would be easy as pie for a competitor to enter the market. To assume that market rates are profitable and that it would be extremely expensive to enter the field is a Mnuchinesque mistake. If you share my assumption (and, apparently, the assumption of the companies themselves) that they would hemorrhage riders if they charged market rates, then it doesn’t matter if Uber achieves quasi-monopoly status — it’s still losing money.

And the problem is even more acute in smaller, less dense markets than NYC and SF. Some of the problems I identified — cars in poor condition, opaque pricing, forced ridesharing — are regulatory failures and/or cases of companies being incompetent. But there’s a reason why outside of the biggest cities cab service tends to be unreliable if it’s available at all outside of transportation hubs and major hotels. Basically, in cities where people don’t take cabs for most trips you face the choice of making it worth their while for drivers to stay on the road when they don’t have passengers, or you’re going to have cases where people want cabs and can’t get them. Given that demand is particularly elastic in places where people generally have cars and rarely use cabs, cab companies are probably going to choose the latter. But this creates a downward spiral — if you need a cab and can’t get one, you’re even less likely to use a cab going forward. I don’t see anything about Uber’s technology that solves this fundamental problem.

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

A follow-up to Mark's post

This is Joseph

I wanted to follow-up on Mark's recent posts. One thing that needs to be carefully thought about with disruptive technologies is whether the legal framework will remain static or not. Consider the example of Amazon and sales tax: for a long time the company benefited from having lower costs due to rules about collecting sales tax in states where it did not have a physical presence. However, success breeds interest in collecting this revenue and, eventually, a successful company can no longer make the argument that special treatment is needed in order to grow a new industry.

With Uber, the fault line is clear -- as long as the drivers are independent contractors that's fine. But the new types of variable pricing are undermining that argument. Felix Salmon:

Now it looks like the CEO might take a leave of absence, which isn't a good sign.

The part of this that is most painful is that Uber is actually probably a very good company in terms of producing a needed product and the huge valuation is causing more harm than good. A real time ride hailing device on smartphones really does add a lot of value by matching customers with cars in a way that used to be quite difficult with a taxi. That's likely to be a product of enduring value. What's harder to see is how it can ever dominate the transportation space enough to make the market capitalization, weighted for risk, seem reasonable.

Addendum: After talking with Mark, he suggested breaking out the steps for the driverless car pivot as being:

I wanted to follow-up on Mark's recent posts. One thing that needs to be carefully thought about with disruptive technologies is whether the legal framework will remain static or not. Consider the example of Amazon and sales tax: for a long time the company benefited from having lower costs due to rules about collecting sales tax in states where it did not have a physical presence. However, success breeds interest in collecting this revenue and, eventually, a successful company can no longer make the argument that special treatment is needed in order to grow a new industry.

With Uber, the fault line is clear -- as long as the drivers are independent contractors that's fine. But the new types of variable pricing are undermining that argument. Felix Salmon:

I do think that it does bring Uber one step closer to being the drivers’ employer, since the drivers are effectively being paid a flat wage for generating a variable revenue stream.The answer is supposed to be driverless cars, but it is unclear that anybody is likely to own this space enough to make it a monopoly. Both traditional car companies and Google look like competitors, and it isn't clear that these companies can be simply muscled aside.

Now it looks like the CEO might take a leave of absence, which isn't a good sign.

The part of this that is most painful is that Uber is actually probably a very good company in terms of producing a needed product and the huge valuation is causing more harm than good. A real time ride hailing device on smartphones really does add a lot of value by matching customers with cars in a way that used to be quite difficult with a taxi. That's likely to be a product of enduring value. What's harder to see is how it can ever dominate the transportation space enough to make the market capitalization, weighted for risk, seem reasonable.

Addendum: After talking with Mark, he suggested breaking out the steps for the driverless car pivot as being:

- Invent and perfect the technology

- Build a car company or partner with an existing car company on favorable terms

- Build the cars -- either by buying a fleet or selling them to customers

- Link the cars to their current taxi service

Some of these steps may be quite challenging. A car is an expensive asset. It is pricey to build them in bulk and it might be hard to convince people to lend them out (unlike the taxi scenario where the owner is able to stay with the valuable asset.

This also suggests that regulatory and insurance issues are tractable. Who is insuring the car and how does it work for periods where it is completely empty? Is summoning an empty car an invitation to theft? It's not that these issues aren't soluble, but there are a lot of steps before success.

Tuesday, June 13, 2017

Ponzi Thresholds

Another post based on Reeves Wiedeman's Uber article in New York magazine. This one sets up a concept I've been meaning to discuss with the tentative name of a Ponzi threshold. The basic idea is that sometimes overhyped companies that start out with viable business plans see their valuation become so inflated that, in order to meet and sustain investor expectations, they have to come up with new and increasingly fantastic longshot schemes, anything that sounds like it might possibly pay off with lottery ticket odds.

Like I said, this is been bouncing around for quite a while. I may have even slipped in a previous reference that I've forgotten about. There are plenty of potential examples, but the following is the first time I've seen the phenomenon spelled out in such naked terms [emphasis added]:

That phrase "looking to justify a huge valuation" is one that you need to contemplate for a few moments, let the logical implications wash over you. As I suggested before, like most New York magazine tech writers, Wiedeman does a good job capturing the telling detail, but is reluctant to draw that final Dr.-Tarr-and-Prof.-Feather conclusion, particularly when it threatens a cherished narrative.

There are at least two layers of crazy here. First, hype and next-big-thingism push Uber's value far beyond any defensible level, then, as reality sets in and investors realize that the original business model, though sound, can never possibly justify the money that's been put into the company, Uber's management responds with a series of more and more improbable proposals in order to keep the buzz going.

The phenomenon is not unique to this company but I can't think of another case this big or this blatant. (And they actually used the term "Ponzi scheme.")

Like I said, this is been bouncing around for quite a while. I may have even slipped in a previous reference that I've forgotten about. There are plenty of potential examples, but the following is the first time I've seen the phenomenon spelled out in such naked terms [emphasis added]:

Meanwhile, in an effort to show potential investors in an IPO that it has multiple revenue streams, Uber has expanded into a variety of industries tangentially related to its core business. In 2015, the company launched Uber Everything, an initiative to figure out how it could move things in addition to people, and when I visited Uber headquarters, the guest Wi-Fi password was a reference to Uber Freight, the company’s attempt to get into trucking. (A former employee said the password often seemed to be a subliminal message encouraging employees to focus on the company’s newest initiatives.) But moving things had its own complications. One former Uber Everything manager said the company had looked at transporting flowers or prescription drugs or laundry but found that the demographic of people who, for example, couldn’t afford a washer and dryer but would pay to have their laundry delivered was a small one. Uber Rush, a delivery service in New York, had become “a nice little business,” the manager said, “but at Uber, you’re looking for a billion-dollar business, not a nice little business.”

It turned out that food delivery was the only area that made much sense, though even that was difficult. In the past year, food-delivery companies SpoonRocket, TinyOwl, Take Eat Easy, and Maple have all ceased operations. Postmates said in 2015 that it could be profitable in 2016, at which point it pushed the date to 2017. Its target is now 2018. “It absolutely does not work as a one-to-one business — picking up a burrito from Chipotle and delivering it,” a former Uber Eats manager said. “It has to be ‘I’m picking up ten orders from Chipotle, and I’m picking up this person next to Chipotle, and I’m gonna drop the burritos off along the way.’ ” Uber Eats has grown significantly, but getting the business up and running had required considerable subsidies, and the manager said it was rumored that a significant portion of the company’s domestic losses were coming from Uber Everything.

Uber’s expansion into an ever-widening gyre of business interests makes sense for a company looking to justify a huge valuation, but it has drawn criticism from some who wonder why the company is moving into so many different markets without becoming profitable in its first one. “It’s a Ponzi scheme of ambition,” Anand Sanwal, a venture-capital analyst, told me. “ ‘We’re gonna raise money on the promise of dominating an industry to come in order to pay for this thing that doesn’t make us money right now.’ ” He had recently conducted an unscientific poll of subscribers to his newsletter asking how many would invest in Uber today, even at a discounted valuation, and 77 percent said they wouldn’t. But the new initiatives have the benefit of keeping everyone excited about the future: In April, Uber held a conference in Dallas to explain why it planned to one day get into flying cars.

That phrase "looking to justify a huge valuation" is one that you need to contemplate for a few moments, let the logical implications wash over you. As I suggested before, like most New York magazine tech writers, Wiedeman does a good job capturing the telling detail, but is reluctant to draw that final Dr.-Tarr-and-Prof.-Feather conclusion, particularly when it threatens a cherished narrative.

There are at least two layers of crazy here. First, hype and next-big-thingism push Uber's value far beyond any defensible level, then, as reality sets in and investors realize that the original business model, though sound, can never possibly justify the money that's been put into the company, Uber's management responds with a series of more and more improbable proposals in order to keep the buzz going.

The phenomenon is not unique to this company but I can't think of another case this big or this blatant. (And they actually used the term "Ponzi scheme.")

Monday, June 12, 2017

Even evil plans require a certain level of competence

This article on Uber by Reeves Wiedeman is less than the sum of its parts, but some of those parts are very good. I particularly liked this observation about the role of competition in the company's valuation and business plans, though Wiedeman does leave one important point unmade. [Emphasis added]

Being an old Arkansas boy, I was born and raised in the Walmart briar patch and I know a thing or two about anti-competitive practices. The giant retailer mastered the art of driving small, locally owned stores out of business by selling products at a loss, then jacking the prices back up when they had a clear field.

There are two essential components to this strategy: sufficiently deep pockets to stay in the game long enough and sufficiently high barriers to reentry so that, when the profit margin starts going back up, a new crop of competitors does not quickly appear. In the case of Walmart, restarting a collapsed local retail economy is next to impossible, but as noted in the article, the barriers to starting a ridesharing service are relatively low, particularly one targeting a single metro area.

So to recap,

1. Uber's plans depend on establishing an objectionable and quite possibly illegal set of international monopolies

2. Even if they do manage to pull this off, they probably won't be able to jacked prices up sufficiently to cover their losses.

To explain its massive losses, Uber and its investors have often cited Amazon, which didn’t turn a year-end profit for ten years as it built out an infrastructure that made the selling of more and more books — and eventually, of everything — cheaper and more efficient the larger it got. But Amazon’s biggest-ever loss was $1.4 billion, half of Uber’s 2016 deficit, and Jeff Bezos responded by cutting 15 percent of his workforce. Plus, Uber’s economics barely resemble Amazon’s. The taxi business doesn’t scale in the same way, and while Uber’s technology is sophisticated, the barriers to entry are relatively low, and Uber has had to fend off various competitors. So far as [transportation-industry analyst Hubert] Horan could tell, there was only one possible path for Uber to meet that $68 billion valuation: eliminate competition.

Uber’s potential aspirations toward monopoly are a sensitive matter — in discussing how Uber Pool became more efficient the more people used it, [Uber’s former head of mapping Brian] McClendon referred to Uber’s ideal state as a “monopoly,” before correcting himself to call it “not a monopoly, but a heavily used service” — and while every company dreams of owning its entire market, the question of whether Uber can do so has become murky. One Uber investor told me he no longer sees ride-hailing as winner-take-all but didn’t want to speak for the company; when I put the question to Rachel Holt, Uber’s head of North American operations, she ducked it by praising the value of competition and saying she didn’t have a crystal ball.

Being an old Arkansas boy, I was born and raised in the Walmart briar patch and I know a thing or two about anti-competitive practices. The giant retailer mastered the art of driving small, locally owned stores out of business by selling products at a loss, then jacking the prices back up when they had a clear field.

There are two essential components to this strategy: sufficiently deep pockets to stay in the game long enough and sufficiently high barriers to reentry so that, when the profit margin starts going back up, a new crop of competitors does not quickly appear. In the case of Walmart, restarting a collapsed local retail economy is next to impossible, but as noted in the article, the barriers to starting a ridesharing service are relatively low, particularly one targeting a single metro area.

So to recap,

1. Uber's plans depend on establishing an objectionable and quite possibly illegal set of international monopolies

2. Even if they do manage to pull this off, they probably won't be able to jacked prices up sufficiently to cover their losses.

Friday, June 9, 2017

Explaining the upsell model with Porky and Daffy

Upsell models are not necessarily innately evil, but they often align the incentives that way.

If the model is based on leveraging customer satisfaction – – if you're happy with the introductory packet, you'll just love the deluxe – – then there is absolutely nothing wrong with the approach. This model is fairly common in healthy, efficient, truly competitive markets. When people are free to choose, the system works.

If, on the other hand, customers are locked in and there are impediments to switching to a different product, this creates an incentive to make the entry level product just good enough to keep people from storming out the door but bad enough that an upgrade is often necessary for a satisfactory experience.

I could illustrate the point with examples from the airline and cable TV industries, but wouldn't you rather just watch the cartoon?

Dime to Retire by MistyIsland1

If the model is based on leveraging customer satisfaction – – if you're happy with the introductory packet, you'll just love the deluxe – – then there is absolutely nothing wrong with the approach. This model is fairly common in healthy, efficient, truly competitive markets. When people are free to choose, the system works.

If, on the other hand, customers are locked in and there are impediments to switching to a different product, this creates an incentive to make the entry level product just good enough to keep people from storming out the door but bad enough that an upgrade is often necessary for a satisfactory experience.

I could illustrate the point with examples from the airline and cable TV industries, but wouldn't you rather just watch the cartoon?

Dime to Retire by MistyIsland1

Thursday, June 8, 2017

Sometimes, "I forgive you" is evangelical-speak for "____ you!"

There is an oft noted truism that combining religion and politics tends to corrupt both. This is especially true with secular evangelicalism, which is the product of the conservative movement's decades long effort to reshape the evangelical movement into an effective political tool.

When it comes to Bible-thumpers, I was born and raised in that particular briar patch. I spent all of my formative years arguing theology, science, and social issues with Baptist and members of even more fundamentalist denominations. We agreed on very little but I always had a degree of respect for at least certain aspects of their philosophy and approach to life.

With the secular evangelicals (the currently dominant wing of the movement that focuses on the Republican agenda and has largely abandoned truly religious concerns), that is no longer the case. The admirable tendencies (spirituality, charity, and the desire to study and understand their sacred texts) have largely been gutted while the worst (intolerance, presumed superiority, and a strong tendency toward persecution complexes) have been amplified.

Those feelings of persecution are an essential part of this story. If you haven't grown up around evangelicals it is difficult to understand how deeply this runs. Stories of martyrdom resonate deeply, conspiracy theories about government plots are common, and, even with the most overwhelming of majorities, evangelicals often tend to think of themselves as a discriminated against minority.

When challenged and especially when losing an argument, these feelings often express themselves with a patronizing "I forgive you" or "God forgives you" (both are basically interchangeable). The implication is always that you are being sinfully unfair to one of God's favorites.

Which takes us to this recent news story from Minnesota:

Based on the news accounts, this seems to be a bizarre non sequitur in the debate, but for those of us from the Bible Belt, the behavior seems completely in character for a secular evangelical. Since she was facing opposition, she felt persecuted and instinctively fell back up on a trusted defense.

It is also worth noting that she invoked the name of Jesus in defense of a position that was not only entirely secular, but which seems in direct contradiction to Christ's clearly stated position on taxation. At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, when the conservative position was in opposition to the Gospels, she rejected the biblical one then suggested that those who disagreed with her were not Christian.

When it comes to Bible-thumpers, I was born and raised in that particular briar patch. I spent all of my formative years arguing theology, science, and social issues with Baptist and members of even more fundamentalist denominations. We agreed on very little but I always had a degree of respect for at least certain aspects of their philosophy and approach to life.

With the secular evangelicals (the currently dominant wing of the movement that focuses on the Republican agenda and has largely abandoned truly religious concerns), that is no longer the case. The admirable tendencies (spirituality, charity, and the desire to study and understand their sacred texts) have largely been gutted while the worst (intolerance, presumed superiority, and a strong tendency toward persecution complexes) have been amplified.

Those feelings of persecution are an essential part of this story. If you haven't grown up around evangelicals it is difficult to understand how deeply this runs. Stories of martyrdom resonate deeply, conspiracy theories about government plots are common, and, even with the most overwhelming of majorities, evangelicals often tend to think of themselves as a discriminated against minority.

When challenged and especially when losing an argument, these feelings often express themselves with a patronizing "I forgive you" or "God forgives you" (both are basically interchangeable). The implication is always that you are being sinfully unfair to one of God's favorites.

Which takes us to this recent news story from Minnesota:

Minnesota Rep. Abigail Whelan, a second-term House legislator from suburban Ramsey, was responding to a question from Democratic Rep. Paul Thissen early Wednesday morning about whether she thinks “benefiting people who are hiding money in Liberia is worth raising taxes on your own constituents.”

Whelan ignored the question and instead sounded off about her religion.

“It might be because it’s late and I’m really tired, but I’m going to take this opportunity to share with the body something I have been grappling with over the past several months, and that is, the games that we play here,” she began, leaving the tax haven discussion in the dust. “I just want you to know, Representative Thissen and the [Democratic] caucus — I forgive you, it is okay, because I have an eternal perspective about this.”

...

“I have an eternal perspective and I want to share that with you and the people listening at home that at the end of the day, when we try to reach an agreement with divided government we win some, we lose some, nobody is really happy, but you know what, happiness and circumstances — not what it’s about,” she continued. “There is actual joy to be found in Jesus Christ, Jesus loves you all. If you would like to get to know him, you’re listening at home, here in this room, please email, call me, would love to talk to you about Jesus, he is the hope of this state and this country.”

Based on the news accounts, this seems to be a bizarre non sequitur in the debate, but for those of us from the Bible Belt, the behavior seems completely in character for a secular evangelical. Since she was facing opposition, she felt persecuted and instinctively fell back up on a trusted defense.

It is also worth noting that she invoked the name of Jesus in defense of a position that was not only entirely secular, but which seems in direct contradiction to Christ's clearly stated position on taxation. At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, when the conservative position was in opposition to the Gospels, she rejected the biblical one then suggested that those who disagreed with her were not Christian.

Wednesday, June 7, 2017

A few thoughts on Twin Peaks

I don't want to spend a lot of time on this one, but a recent post by Ken Levine about declining television viewership numbers got me to thinking. The content bubble story is big and complicated and inextricably intertwined with other big, complex stories such as media consolidation. I have found that it is useful, when following such a story, to take at least brief note of major developments so that you will have a record of them when you go back and try to make sense of things.

With that in mind here are a few regarding Twin Peaks:

1. This was a hugely expensive undertaking. Between the length, the ambition, and the names of those in front of and behind the camera, we are talking substantial production cost. Add to that huge marketing numbers. In addition to the considerable advertising budget, Twin Peaks has gotten a vast amount of media coverage. At the risk of seeming a bit cynical, every time you see a story or read an interview about a major upcoming studio release, you should think of it as being paid for by the studio in some way. A few journalist actually receive some kind of compensation (monetary or otherwise) for running the story. Others are happy to let some PR flack write their copy. On the next level up you get journalists who are willing to trade favorable and extensive coverage for access. Then finally, there is the more subtle but still essential greasing of the wheels, having the people and resources available to keep the PR running smoothly. These things cost a lot of money.

2. Given this amount of money, the viewership numbers we are seeing are not good.

3. And don't give too much weight to all the talk about record setting sign-ups. You will notice a certain vagueness about this metric. For instance, there doesn't seem to be much if any discussion of absolute numbers. I don't believe that Showtime has ever had an event this heavily hyped. We cannot, therefore, assume that the previous record was all that impressive. Probably more importantly, many of these sign-ups are presumably for 30 day free trials. As far as I can tell, we have little idea how many people signed up and even less idea how many of those will become paying customers.

4. There is, however, some good news for the company. Supposedly at David Lynch's insistence, all but the first few episodes will be coming out one at a time. This means that anyone dropping after the first 30 days will miss most of the series. Furthermore, as best I can tell, Showtime's parent company CBS apparently has a large ownership share in Twin Peaks. I would need to do quite a bit of research to be certain, but CBS does own Spelling Productions, which was one of the companies behind the original series. I also noticed that CBS.com and the CBS streaming service have both offered original Twin Peaks for a while now. If the franchise is a CBS property, this means that all sorts of secondary revenue streams will flow back to the parent company. The investment in the new series makes the old show more viable. It also opens up the possibility of future movies and other projects.

5. That said, these numbers still do not look good and they raise real questions about the currently hot model of dusting off some old cult TV show. These programs have built-in name recognition and they are amazingly hype-friendly, but if this level of promotion brings in less than 1 million viewers, that is a very bad sign.

With that in mind here are a few regarding Twin Peaks:

1. This was a hugely expensive undertaking. Between the length, the ambition, and the names of those in front of and behind the camera, we are talking substantial production cost. Add to that huge marketing numbers. In addition to the considerable advertising budget, Twin Peaks has gotten a vast amount of media coverage. At the risk of seeming a bit cynical, every time you see a story or read an interview about a major upcoming studio release, you should think of it as being paid for by the studio in some way. A few journalist actually receive some kind of compensation (monetary or otherwise) for running the story. Others are happy to let some PR flack write their copy. On the next level up you get journalists who are willing to trade favorable and extensive coverage for access. Then finally, there is the more subtle but still essential greasing of the wheels, having the people and resources available to keep the PR running smoothly. These things cost a lot of money.

2. Given this amount of money, the viewership numbers we are seeing are not good.

With that, 506,000 viewers watched the two-hour, two-episode 9 PM premiere of the David Lynch and Mark Frost series Sunday, according to Nielsen. Among adults 18-49, the return of Agent Dale Cooper, Laura Palmer and more of the mystery of the Pacific Northwest town snagged a 0.2 rating.

3. And don't give too much weight to all the talk about record setting sign-ups. You will notice a certain vagueness about this metric. For instance, there doesn't seem to be much if any discussion of absolute numbers. I don't believe that Showtime has ever had an event this heavily hyped. We cannot, therefore, assume that the previous record was all that impressive. Probably more importantly, many of these sign-ups are presumably for 30 day free trials. As far as I can tell, we have little idea how many people signed up and even less idea how many of those will become paying customers.

4. There is, however, some good news for the company. Supposedly at David Lynch's insistence, all but the first few episodes will be coming out one at a time. This means that anyone dropping after the first 30 days will miss most of the series. Furthermore, as best I can tell, Showtime's parent company CBS apparently has a large ownership share in Twin Peaks. I would need to do quite a bit of research to be certain, but CBS does own Spelling Productions, which was one of the companies behind the original series. I also noticed that CBS.com and the CBS streaming service have both offered original Twin Peaks for a while now. If the franchise is a CBS property, this means that all sorts of secondary revenue streams will flow back to the parent company. The investment in the new series makes the old show more viable. It also opens up the possibility of future movies and other projects.

5. That said, these numbers still do not look good and they raise real questions about the currently hot model of dusting off some old cult TV show. These programs have built-in name recognition and they are amazingly hype-friendly, but if this level of promotion brings in less than 1 million viewers, that is a very bad sign.

Tuesday, June 6, 2017

Immigration woes

This is Joseph

This story has some rather chilling implications. Duncan Black makes the point:

This story has some rather chilling implications. Duncan Black makes the point:

I bet half the country would have a hard time producing clear evidence of citizenship, and 99.9% couldn't do it on the spot.In a sense this new normal of detention seems to be most dangerous to US-born citizens, who really don't have anywhere to be deported to (they end up as stateless persons). From the article:

Plascencia and her family say the experience has shaken their ideas about the protections they are entitled to as American citizens. Sepulveda said she is now afraid to leave the U.S., the country she was born in.The real issue seems to be the lack of an apologetic response. A simple "we made a mistake" statement would go a long way to making this situation clear as an accident and not part of a new normal in terms of policing. That would have done more than anything else to reassure people (including those directly involved) and fix the otherwise terrible optics of the situation.

Monday, June 5, 2017

And how the hell do you make an adverb out of "grammar"?

Though it lacks the immediate punchline quality of Soylent and Juicero, Grammarly maybe an even better example of the dysfunctional Silicon Valley venture capitalist culture. From Christina Warren writing for Gizmodo.

Warren then quotes the Wall Street Journal:

The company raised ludicrous amounts of money.

It proposed an unrealistically expensive product...

An unrealistically expensive product that offered no immediately obvious improvement in functionality over what you already have available if you are running Microsoft office.

The proposal was based largely on trendy buzzwords...

Buzzwords that the CEO apparently did not understand the meaning of. What's described here is not artificial intelligence or machine learning, it is a fairly dumb algorithm. Furthermore, while this would be a good approach for something like an autocorrect function, it is (as Warren notes) a terrible approach for grammar software.

If only it were named for a bad 70s sci-fi picture it would be perfect.

For a company raising its first round of investment (Grammarly was founded in 2009 and has been bootstrapped ever since), $110 million is incredibly significant. As Bloomberg notes, this is among the largest initial investments for a startup recently.

...

Intrigued by the buzz, I decided to try the free version of Grammarly’s Chrome plugin (the more robust premium version costs an eye-watering $30 a month) and see what could possibly be worth the hype.

In practice, Grammarly is basically a web-version of the Grammar check feature Microsoft Word has had since, like, 1995. Also, in my experience, the free version only works so well. The service will catch major typos, but plenty of errors, both in spelling and usage, go undetected.

Warren then quotes the Wall Street Journal:

Grammarly learns from the vast amount of writing it ingests, and it adjusts based on usage. In a simple example, when people write “Hi John” in an email, Grammarly was suggesting people add a comma. “But nobody used that,” Mr. Lytvyn said. “So we dropped it.”Why is this such a good example of what's wrong with the money men up the the Bay Area...

The company raised ludicrous amounts of money.

It proposed an unrealistically expensive product...

An unrealistically expensive product that offered no immediately obvious improvement in functionality over what you already have available if you are running Microsoft office.

The proposal was based largely on trendy buzzwords...

Buzzwords that the CEO apparently did not understand the meaning of. What's described here is not artificial intelligence or machine learning, it is a fairly dumb algorithm. Furthermore, while this would be a good approach for something like an autocorrect function, it is (as Warren notes) a terrible approach for grammar software.

If only it were named for a bad 70s sci-fi picture it would be perfect.

Friday, June 2, 2017

Living in a post-truth world

This is Joseph.

Larry Summers on the heroic assumptions needed to make the current budget deficit neutral:

Two, this is a pretty good estimate of the maximum effect of supply side reforms. Moving the tax rate from 70 to 28 percent is about the entire range of plausible rates, and increasing employment could be a intermediate step here. But that would suggest a fairly modest effect, given that the US growth rate from 1948 to 2017 was 2.00%.

If you see the drop in employment as being unrelated to the tax cuts (recovery from recession), then Reagan had the average growth rate of the post-WWII US. You know, it might be possible that tax rates aren't a key driver of economic growth, compared to factors like good government. Just thinking out loud here.

And this leads to my last and most puzzling observation. If government is run like a business then why do they keep cutting revenue? Does comcast cut prices in the absence of competition? Or is this a principal agent problem writ large?

h/t Economist's View

Larry Summers on the heroic assumptions needed to make the current budget deficit neutral:

The Trump economic team has not engaged in serious analysis or been in dialogue with those who are capable of it so they have had nothing to say in defense of their forecast except extravagant claims for their policies. Taking their supply-side perspective, do they really believe that through tax cuts and deregulation they are going to accomplish more than Ronald Reagan, who after all reduced the top tax rate from 70 to 28 percent? Between 1981 and 1988, GDP per adult grew by an average of 2.5 percent, distinctly slower than what they are forecasting. Even this figure reflects a substantial cyclical tail wind from the decline in unemployment from 7.6 percent to 5.5 percent (which from Okun’s law implies adding about half a percent to GDP growth) — something unavailable in the present context.Two thoughts here. One, if assumptions this heroic are allowable then there is really no point to doing forecasts, as they are too unlikely to reflect reality. Maybe we will have a period that is a positive outlier, but maybe it will be a negative outlier as well. One has to argue for the central tendency as the most likely outcome and this isn't in line with past rates of growth.

Two, this is a pretty good estimate of the maximum effect of supply side reforms. Moving the tax rate from 70 to 28 percent is about the entire range of plausible rates, and increasing employment could be a intermediate step here. But that would suggest a fairly modest effect, given that the US growth rate from 1948 to 2017 was 2.00%.

If you see the drop in employment as being unrelated to the tax cuts (recovery from recession), then Reagan had the average growth rate of the post-WWII US. You know, it might be possible that tax rates aren't a key driver of economic growth, compared to factors like good government. Just thinking out loud here.

And this leads to my last and most puzzling observation. If government is run like a business then why do they keep cutting revenue? Does comcast cut prices in the absence of competition? Or is this a principal agent problem writ large?

h/t Economist's View

Thursday, June 1, 2017

Liz Spayd was a disaster for the New York Times because she was exactly what the paper wanted

From TPM:

For a long time now, we have been talking about the central paradox that prevents the New York Times from moving forward. Going back all the way to the 19th century, the New York Times has been widely noted as being snobbish, prissy, and holier than thou. Perhaps from the paper's very inception, The New York Times has been defined by an unshakable belief in its own superiority.

While this was always a dangerous assumption, for most of the paper's history the risk was minimized by high quality and standards of journalism . When things started to go bad, however, the NYT was fundamentally incapable of honestly assessing and effectively addressing the problems. Judith Miller was not an anomaly; she was an unsurprising and completely representative result of the culture of the paper.

The great irony of a New York Times public editor position is that the more one is needed, the less doable the job becomes. When the paper was having a good run (and it has had quite a few), a public editor could point out real flaws that the paper was willing to address, because the criticism did not undermine any fundamental tenet of superiority. Unfortunately, the past quarter century or so has marked an all time low for the gray lady. Here is a partial list:

Whitewater;

Bush V Gore;

The Iraq war;

False balance;

Credulous reporting of untrustworthy anonymous sources;

Weakness in the face of (mostly conservative) pressure;

Inadequate coverage bordering on complicity with stories like swift boating and birtherism;

And finally, a determination to cling to all vendettas with the Clintons that arguably resulted in the Trump presidency.

Some of the public editors, most notably Margaret Sullivan, aggressively pursued their duties and tried to give voice to the most valid criticisms being made about the paper. The NYT, however, showed no interest in acting to rectify those problems and often gave the impression of not even caring.

Perhaps the selection of Liz Spayd was a reaction against the blunt honesty of Sullivan. From the very beginning, Spayd publicly and enthusiastically bought into the best-newspaper-ever belief system. It permeated her columns and put a clear boundary on her criticisms. She was exactly what her bosses had always wanted and the result was a PR nightmare. It turned out that having a public editor who instinctively cited with her editors over the public was a bad idea.

Here is a sample from last year:

From Wikipedia

I don't want to impose a template, but generally one expects public editors to serve as the internal representative of external critical voices, or at least to see to it that these voices get a fair hearing. A typical column might start with acknowledging complaints about something like the paper's lack of coverage of poor neighborhoods. The public editor would then discuss some possible lapses on the paper's part, get some comments from the editor in charge, and then, as a rule, either encourage the paper to improve its coverage in this area or, at the very least, take a neutral position acknowledging that both the critics and the paper have a point.

Here are some examples from two previous public editors of the New York Times.

Clark Hoyt

Margaret Sullivan

But these are strange days at the New York Times and the new public editor is writing columns that are not only a sharp break with those of her predecessors, but seem to violate the very spirit of the office.

In particular, Liz Spayd is catching a great deal of flak for a piece that almost manages to invert the typical public editor column. It starts by grossly misrepresenting widespread criticisms of the paper, goes on to openly attack the critics making the charges, then pleads with the paper's staff to toe the editorial line and ignore the very voices that a public editor would normally speak for .

[Emphasis added]

The Truth About ‘False Balance’

There has been a great deal of speculation as to what drives false equivalency, with the leading contenders being a desire to maintain access to high-placed sources, long-standing personal biases against certain politicians, a fear of reprisal, a desire to avoid charges of liberal bias, and simple laziness (a cursory both-sides-do-it story is generally much easier to write than a well investigated piece). Caring too much about fairness hardly ever makes the list and it certainly has no place in the definition.

Spayd then accuses the people making these charges of being irrational, shortsighted, and partisan.

But, as Jonathan Chait points out, Weisberg has no record of being a Hillary Clinton booster. The charge here is completely circular. He is partisan because he made a highly critical comment about Donald Trump and he made a highly critical comment about Donald Trump because he is partisan.

But the most extraordinary part of the piece and one which reminds us just how strange the final days of 2016 are becoming is the conclusion.

Putting aside the curious characterization of the Florida AG investigation as a tax evasion story (which is a lot like describing the Watergate scandal as a burglary story or Al Capone as a tax evader), equating her paper's pursuit of the Clinton foundation with the Washington Post's coverage of Trump is simply surreal on a number of levels.

For starters, none of the Clinton foundation stories have revealed significant wrongdoing. Even Spayd, who is almost comically desperate to portray her employer in the best possible light, had to concede that “some foundation stories revealed relatively little bad behavior, yet were written as if they did.” By comparison, the Washington Post investigation continues to uncover self-dealing, misrepresentation, tax evasion, misuse of funds, failure to honor obligations, ethical violations, general sleaziness and blatant quid prop quo bribery.

More importantly, the Washington Post has explicitly attacked and implicitly abandoned Spayd's position. Here's how the Post summed it up in an editorial that appeared two days before the NYT column.

Charles Pierce's characteristically pithy response to this editorial was "The Washington Post Just Declared War on The New York Times -- And with good reason, too."

If is almost as if Spayd thinks it's 2000, when the NYT could set the conventional wisdom, could decide which narratives would followed and which public figures would be lauded or savaged. Spayd does understand that there is a battle going on for the soul of journalism, but she does not seem to understand that the alliances have changed, and the New York Times is about to find itself in a very lonely position.

[Apologies for earlier cut and paste errors.]

The publisher of the New York Times announced Wednesday that the paper was eliminating its public editor position, a role currently held by Liz Spayd.

“The responsibility of the public editor – to serve as the reader’s representative – has outgrown that one office,” Arthur Sulzberger Jr. wrote in a memo to colleagues, which was obtained by TPM. “Our business requires that we must all seek to hold ourselves accountable to our readers. When our audience has questions or concerns, whether about current events or our coverage decisions, we must answer them ourselves.”

For a long time now, we have been talking about the central paradox that prevents the New York Times from moving forward. Going back all the way to the 19th century, the New York Times has been widely noted as being snobbish, prissy, and holier than thou. Perhaps from the paper's very inception, The New York Times has been defined by an unshakable belief in its own superiority.

While this was always a dangerous assumption, for most of the paper's history the risk was minimized by high quality and standards of journalism . When things started to go bad, however, the NYT was fundamentally incapable of honestly assessing and effectively addressing the problems. Judith Miller was not an anomaly; she was an unsurprising and completely representative result of the culture of the paper.

The great irony of a New York Times public editor position is that the more one is needed, the less doable the job becomes. When the paper was having a good run (and it has had quite a few), a public editor could point out real flaws that the paper was willing to address, because the criticism did not undermine any fundamental tenet of superiority. Unfortunately, the past quarter century or so has marked an all time low for the gray lady. Here is a partial list:

Whitewater;

Bush V Gore;

The Iraq war;

False balance;

Credulous reporting of untrustworthy anonymous sources;

Weakness in the face of (mostly conservative) pressure;

Inadequate coverage bordering on complicity with stories like swift boating and birtherism;

And finally, a determination to cling to all vendettas with the Clintons that arguably resulted in the Trump presidency.

Some of the public editors, most notably Margaret Sullivan, aggressively pursued their duties and tried to give voice to the most valid criticisms being made about the paper. The NYT, however, showed no interest in acting to rectify those problems and often gave the impression of not even caring.

Perhaps the selection of Liz Spayd was a reaction against the blunt honesty of Sullivan. From the very beginning, Spayd publicly and enthusiastically bought into the best-newspaper-ever belief system. It permeated her columns and put a clear boundary on her criticisms. She was exactly what her bosses had always wanted and the result was a PR nightmare. It turned out that having a public editor who instinctively cited with her editors over the public was a bad idea.

Here is a sample from last year:

"Why do you hate us for caring too much?" – – Dispatches from a besieged institution

Public EditorFrom Wikipedia

The job of the public editor is to supervise the implementation of proper journalism ethics at a newspaper, and to identify and examine critical errors or omissions, and to act as a liaison to the public. They do this primarily through a regular feature on a newspaper's editorial page. Because public editors are generally employees of the very newspaper they're criticizing, it may appear as though there is a possibility for bias. However, a newspaper with a high standard of ethics would not fire a public editor for a criticism of the paper; the act would contradict the purpose of the position and would itself be a very likely cause for public concern.

I don't want to impose a template, but generally one expects public editors to serve as the internal representative of external critical voices, or at least to see to it that these voices get a fair hearing. A typical column might start with acknowledging complaints about something like the paper's lack of coverage of poor neighborhoods. The public editor would then discuss some possible lapses on the paper's part, get some comments from the editor in charge, and then, as a rule, either encourage the paper to improve its coverage in this area or, at the very least, take a neutral position acknowledging that both the critics and the paper have a point.

Here are some examples from two previous public editors of the New York Times.

Clark Hoyt

The short answer is that a television critic with a history of errors wrote hastily and failed to double-check her work, and editors who should have been vigilant were not. But a more nuanced answer is that even a newspaper like The Times, with layers of editing to ensure accuracy, can go off the rails when communication is poor, individuals do not bear down hard enough, and they make assumptions about what others have done. Five editors read the article at different times, but none subjected it to rigorous fact-checking, even after catching two other errors in it. And three editors combined to cause one of the errors themselves.

Margaret Sullivan

Mistakes are bound to happen in the news business, but some are worse than others.

What I’ll lay out here was a bad one. It involved a failure of sufficient skepticism at every level of the reporting and editing process — especially since the story in question relied on anonymous government sources, as too many Times articles do.

…

The Times needs to fix its overuse of unnamed government sources. And it needs to slow down the reporting and editing process, especially in the fever-pitch atmosphere surrounding a major news event. Those are procedural changes, and they are needed. But most of all, and more fundamental, the paper needs to show far more skepticism – a kind of prosecutorial scrutiny — at every level of the process.

Two front-page, anonymously sourced stories in a few months have required editors’ notes that corrected key elements – elements that were integral enough to form the basis of the headlines in both cases. That’s not acceptable for Times readers or for the paper’s credibility, which is its most precious asset.

If this isn’t a red alert, I don’t know what will be.

But these are strange days at the New York Times and the new public editor is writing columns that are not only a sharp break with those of her predecessors, but seem to violate the very spirit of the office.

In particular, Liz Spayd is catching a great deal of flak for a piece that almost manages to invert the typical public editor column. It starts by grossly misrepresenting widespread criticisms of the paper, goes on to openly attack the critics making the charges, then pleads with the paper's staff to toe the editorial line and ignore the very voices that a public editor would normally speak for .

[Emphasis added]

The Truth About ‘False Balance’

False balance, sometimes called “false equivalency,” refers disparagingly to the practice of journalists who, in their zeal to be fair, present each side of a debate as equally credible, even when the factual evidence is stacked heavily on one side.

There has been a great deal of speculation as to what drives false equivalency, with the leading contenders being a desire to maintain access to high-placed sources, long-standing personal biases against certain politicians, a fear of reprisal, a desire to avoid charges of liberal bias, and simple laziness (a cursory both-sides-do-it story is generally much easier to write than a well investigated piece). Caring too much about fairness hardly ever makes the list and it certainly has no place in the definition.

Spayd then accuses the people making these charges of being irrational, shortsighted, and partisan.

I can’t help wondering about the ideological motives of those crying false balance, given that they are using the argument mostly in support of liberal causes and candidates. CNN’s Brian Stelter focused his show, “Reliable Sources,” on this subject last weekend. He asked a guest, Jacob Weisberg of Slate magazine, to frame the idea of false balance. Weisberg used an analogy, saying journalists are accustomed to covering candidates who may be apples and oranges, but at least are still both fruits. In Trump, he said, we have not fruit but rancid meat. That sounds like a partisan’s explanation passed off as a factual judgment.

But, as Jonathan Chait points out, Weisberg has no record of being a Hillary Clinton booster. The charge here is completely circular. He is partisan because he made a highly critical comment about Donald Trump and he made a highly critical comment about Donald Trump because he is partisan.

But the most extraordinary part of the piece and one which reminds us just how strange the final days of 2016 are becoming is the conclusion.

I hope Times journalists won’t be intimidated by this argument. I hope they aren’t mindlessly tallying up their stories in a back room to ensure balance, but I also hope they won’t worry about critics who claim they are. What’s needed most is forceful, honest reporting — as The Times has produced about conflicts circling the foundation; and as The Washington Post did this past week in surfacing Trump’s violation of tax laws when he made a $25,000 political contribution to a campaign group connected to Florida’s attorney general as her office was investigating Trump University.

Fear of false balance is a creeping threat to the role of the media because it encourages journalists to pull back from their responsibility to hold power accountable. All power, not just certain individuals, however vile they might seem.

Putting aside the curious characterization of the Florida AG investigation as a tax evasion story (which is a lot like describing the Watergate scandal as a burglary story or Al Capone as a tax evader), equating her paper's pursuit of the Clinton foundation with the Washington Post's coverage of Trump is simply surreal on a number of levels.

For starters, none of the Clinton foundation stories have revealed significant wrongdoing. Even Spayd, who is almost comically desperate to portray her employer in the best possible light, had to concede that “some foundation stories revealed relatively little bad behavior, yet were written as if they did.” By comparison, the Washington Post investigation continues to uncover self-dealing, misrepresentation, tax evasion, misuse of funds, failure to honor obligations, ethical violations, general sleaziness and blatant quid prop quo bribery.

More importantly, the Washington Post has explicitly attacked and implicitly abandoned Spayd's position. Here's how the Post summed it up in an editorial that appeared two days before the NYT column.

Imagine how history would judge today’s Americans if, looking back at this election, the record showed that voters empowered a dangerous man because of . . . a minor email scandal. There is no equivalence between Ms. Clinton’s wrongs and Mr. Trump’s manifest unfitness for office.

Charles Pierce's characteristically pithy response to this editorial was "The Washington Post Just Declared War on The New York Times -- And with good reason, too."

If is almost as if Spayd thinks it's 2000, when the NYT could set the conventional wisdom, could decide which narratives would followed and which public figures would be lauded or savaged. Spayd does understand that there is a battle going on for the soul of journalism, but she does not seem to understand that the alliances have changed, and the New York Times is about to find itself in a very lonely position.

[Apologies for earlier cut and paste errors.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)