Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, October 5, 2018

If you're tired of the Mars rants, just skip to the Rocket Man cover

This Neil Degrasse Tyson segment from the Tonight Show was amusing – – both he and Stephen Colbert are good at this sort of thing and play well off of each other – – but I'm including it because it hits on a point that I've alluded to in previous conversations of space exploration and the vanity aerospace industry.

Much, arguably most, of the 21st century discussion of man's expansion into and utilization of outer space is based on an implicit and often explicit colonial era framework. This includes such respectable news organizations as the New York Times, NPR, the BBC, and most recently and egregiously the Atlantic.

Any time you see the term "Mars colony," you know you are in trouble. Almost inevitably what follows will assume that the second half of the 21st century will basically just be a remake of the 17th and 18th, despite causes and conditions being all but completely non-analogous. I have neither the time nor the knowledge to go into detail here, but if you will forgive the oversimplification, the original system was based on habitable, arable lands which generally offered significant potential for trade and were easily accessed and conquered and which required a great deal of labor in order to pay off for the colonizing power.

None of this applies to Mars or any other body in the solar system. Outside of certain research questions, there are for the foreseeable future very few economically sound arguments for a human presence in space. Even if something like Martian mining proves viable, any work on the surface of the planet will be done largely, perhaps entirely, by autonomous and semiautonomous robots. This is true now and it will certainly be more true with the AI and robotics of 2050. Based on purely practical considerations, there will be no way to justify more than the most minimal of human presences on the red planet.

This leaves us with various romantic arguments about man's need to reach out to strange lands. [Insert super cut of inspirational Star Trek speeches here.] 100 or so years ago, you might have been able to make a reasonably convincing argument for the explore and settle model. Multiple high profile polar expeditions dominated the news while scientist were for the first time probing the depths of the ocean with dredges and other specialized instruments. The idea of cities in previously inhospitable or even impossible places captured the public imagination.

But this is not 1918. This is 2018 and, as Neil Degrasse Tyson points out, no one is lining up to colonize Antarctica, nor do we have undersea settlements or subterranean metropolises. Hell, we have trouble getting people to move to North Dakota.

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Repost -- some thoughts on poll volatility and self-selection

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Life on 49-49

[Following up on this post, here are some more (barely) pre-election thoughts on how polls gang aft agley. I believe Jonathan Chait made some similar points. Some of Nate Silver's critics also wandered into some neighboring territory (with the important distinction that Chait understood the underlying concepts)]Assume that there's an alternate world called Earth 49-49. This world is identical to ours in all but one respect: for almost all of the presidential campaign, 49% of the voters support Obama and 49% support Romney. There has been virtually no shift in who plans to vote for whom.

Despite this, all of the people on 49-49 believe that they're on our world, where large segments of the voters are shifting their support from Romney to Obama then from Obama to Romney. They weren't misled to this belief through fraud -- all of the polls were administered fairly and answered honestly -- nor was it a case of stupidity or bad analysis -- the political scientists on 49-49 are highly intelligent and conscientious -- rather it had to do with the nature of polling.

Pollsters had long tracked campaigns by calling random samples of potential voters. As campaign became more drawn out and journalistic focus shifted to the horse race aspects of election, these phone polls proliferated. At the same time, though, the response rates dropped sharply, going from more than one in three to less than one in ten.

A big drop in response rates always raises questions about selection bias since the change may not affect all segments of the population proportionally (more on that -- and this report -- later). It also increases the potential magnitude of these effects.

Consider these three scenarios. What would happen if you could do the following (in the first two cases, assume no polling bias):

A. Convince one percent of undecideds to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent stays at 49 -- one percent poll advantage

B. Convince one percent of opponent's supporters to support you. Your support goes to 50 while your opponent drops to 48 -- two percent poll advantage

C. Convince an additional one percent of your supporters to answer the phone when a pollster calls. You go to over 51% while your opponent drops to under 47%-- around a five percent poll advantage.

Of course, no one was secretly plotting to game the polls, but poll responses are basically just people agreeing to talk to you about politics, and lots of things can affect people's willingness to talk about their candidate, including things that would almost never affect their actual votes (at least not directly but more on that later).

In 49-49, the Romney campaign hit a stretch of embarrassing news coverage while Obama was having, in general, a very good run. With a couple of exceptions, the stories were trivial, certainly not the sort of thing that would cause someone to jump the substantial ideological divide between the two candidates so, none of Romney's supporters shifted to Obama or to undecided. Many did, however, feel less and less like talking to pollsters. So Romney's numbers started to go down which only made his supporters more depressed and reluctant to talk about their choice.

This reluctance was already just starting to fade when the first debate came along. As Josh Marshall has explained eloquently and at great length since early in the primaries, the idea of Obama, faced with a strong attack and deprived of his teleprompter, collapsing in a debate was tremendously important and resonant to the GOP base. That belief was a major driver of the support for Gingrich, despite all his baggage; no one ever accused Newt of being reluctant to go for the throat.

It's not surprising that, after weeks of bad news and declining polls, the effect on the Republican base of getting what looked very much like the debate they'd hoped for was cathartic. Romney supporters who had been avoiding pollsters suddenly couldn't wait to take the calls. By the same token. Obama supporters who got their news from Ed Schultz and Chris Matthews really didn't want to talk right now.

The polls shifted in Romney's favor even though, had the election been held the week after the debate, the result would have been the same as it would have been had the election been held two weeks before -- 49% to 49%. All of the changes in the polls had come from core voters on both sides. The voters who might have been persuaded weren't that interested in the emotional aspect of the conventions and the debates and were already familiar with the substantive issues both events raised.

So response bias was amplified by these factors:

1. the effect was positively correlated with the intensity of support

2. it was accompanied by matching but opposite effects on the other side

3. there were feedback loops -- supporters of candidates moving up in the polls were happier and more likely to respond while supporters of candidates moving down had the opposite reaction.

You might wonder how the pollsters and political scientists of this world missed this. The answer that they didn't. They were concerned about selection effects and falling response rates, but the problems with the data were difficult to catch definitively thanks to some serious obscuring factors:

1. Researchers have to base their conclusions off of the historical record when the effect was not nearly so big.

2. Things are correlated in a way that's difficult to untangle. The things you would expect to make supporters less enthusiastic about talking about their candidate are often the same things you'd expect to lower support for that candidate

3. As mentioned before, there are compensatory effects. Since response rates for the two parties are inversely related, the aggregate is fairly stable.

4. The effect of embarrassment and elation tend to fade over time so that most are gone by the actual election.

5. There's a tendency to converge as the election approaches. Mainly because likely voter screens become more accurate.

6. Poll predictions can be partially self-fulfilling. If the polls indicate a sufficiently low chance of winning, supporters can become discouraged, allies can desert you and money can dry up. The result is, again, convergence.

For the record, I don't think we live on 49-49. I do, however, think that at least some of the variability we've seen in the polls can be traced back to selection effects similar to those described here and I have to believe it's likely to get worse.

Wednesday, October 3, 2018

Fixed costs, marginal costs, and the Zeno project management rule of thumb.

Having spent a long time now chronicling bad journalism, one of the conclusions that keeps coming up again and again is that 21st-century journalists have a serious problem dealing with the obvious, particularly when it goes against the story being told by the subject of a piece. This inability to address these naked emperor situations shows up in every area of news coverage – – political examples alone would fill volumes – – but let's focus on one egregious example, high-speed intra-city rail, best illustrated by a recent proposal from, to no one's great surprise, Elon Musk.

There's a very good rule of thumb when you're trying to devise complex solutions to get you as close as possible to some upper bound: if you think of your progress in terms of a succession of steps that take you halfway from where you are to where you want to be, you should assume that each step will cost more than the previous step. In other words, getting halfway to your goal will be cheaper than going from half to one fourth and going from half to one fourth will be cheaper than going from 1/4 to 1/8, and so on. (I'd probably start using the word "asymptote" here if this were the kind of post where I was going to use words like "asymptote.")

Clearly, this is closely related to the concept of diminishing returns and it immediately suggests that plans which promise complete solutions to thorny problems should be viewed with great skepticism. Recent case in point, the vague pitch for a vague proposal for a vague plan for getting pedestrian deaths in Los Angeles down to zero. With a well-functioning press corps, offers of perfection should be a hard sell.

Unfortunately, this takes us into the bullshit territory of aspirational language and various other magical heuristics. The willingness to commit to the impossible has increasingly come to be seen as a sign of seriousness and visionary thinking. Playing by these rules, the very fact that a claim is unbelievable actually makes it more credible.

While it is possible to come up with exceptions to the Zeno rule, it holds for an exceptionally large number of cases, particularly when you take into account fixed and marginal costs. Let's get back to the subject of transportation.

Consider two flights, one from Los Angeles to San Francisco, the other to some city east of the Mississippi. LA has a fair number of major airports, but they all tend to be understandably on the outskirts so that, if you are starting from a fairly central location, it is easy to find yourself a considerable distance away from the closest option. Between driving, parking, and getting through security, let's call it two hours from stepping out your front door to stepping on the plane (to simplify things, we'll treat the other airport as your final destination).

We'll round up the flying time from Los Angeles to San Francisco to an hour and call the flying time to our unnamed East Coast city eight hours, giving us a total of three hours and ten hours respectively. In terms of travel time and airspeed, those two hours are fixed cost while the rest are marginal. Increasing airspeed would decrease the second but leave the first unchanged, thus paying extra for a much faster airplane would make a great deal of sense for the long flight but almost none for the short one.

Once again, apologies for spending this much time making obvious points, but it's good to have these things in mind when we consider the following:

There's a very good rule of thumb when you're trying to devise complex solutions to get you as close as possible to some upper bound: if you think of your progress in terms of a succession of steps that take you halfway from where you are to where you want to be, you should assume that each step will cost more than the previous step. In other words, getting halfway to your goal will be cheaper than going from half to one fourth and going from half to one fourth will be cheaper than going from 1/4 to 1/8, and so on. (I'd probably start using the word "asymptote" here if this were the kind of post where I was going to use words like "asymptote.")

Clearly, this is closely related to the concept of diminishing returns and it immediately suggests that plans which promise complete solutions to thorny problems should be viewed with great skepticism. Recent case in point, the vague pitch for a vague proposal for a vague plan for getting pedestrian deaths in Los Angeles down to zero. With a well-functioning press corps, offers of perfection should be a hard sell.

Unfortunately, this takes us into the bullshit territory of aspirational language and various other magical heuristics. The willingness to commit to the impossible has increasingly come to be seen as a sign of seriousness and visionary thinking. Playing by these rules, the very fact that a claim is unbelievable actually makes it more credible.

While it is possible to come up with exceptions to the Zeno rule, it holds for an exceptionally large number of cases, particularly when you take into account fixed and marginal costs. Let's get back to the subject of transportation.

Consider two flights, one from Los Angeles to San Francisco, the other to some city east of the Mississippi. LA has a fair number of major airports, but they all tend to be understandably on the outskirts so that, if you are starting from a fairly central location, it is easy to find yourself a considerable distance away from the closest option. Between driving, parking, and getting through security, let's call it two hours from stepping out your front door to stepping on the plane (to simplify things, we'll treat the other airport as your final destination).

We'll round up the flying time from Los Angeles to San Francisco to an hour and call the flying time to our unnamed East Coast city eight hours, giving us a total of three hours and ten hours respectively. In terms of travel time and airspeed, those two hours are fixed cost while the rest are marginal. Increasing airspeed would decrease the second but leave the first unchanged, thus paying extra for a much faster airplane would make a great deal of sense for the long flight but almost none for the short one.

Once again, apologies for spending this much time making obvious points, but it's good to have these things in mind when we consider the following:

Elon Musk's company proposes 3.6-mile tunnel to Dodger Stadium

Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk’s tunneling company on Wednesday announced a proposal to build another tunnel in Los Angeles, a 3.6-mile underground route that would carry fans between Dodger Stadium and a nearby Metro subway station.

The Boring Co. said the Dugout Loop would be a “zero-emissions, high-speed” transportation system that could carry fans in about four minutes between Elysian Park and a Metro station along Vermont Avenue, at Beverly Boulevard, Santa Monica Boulevard or Sunset Boulevard.

Pods carrying passengers would whiz through the tunnel at speeds of up to 150 mph, resting on self-driving platforms called “skates,” the Boring Co. said. The trip would cost about $1, and riders would purchase tickets in advance through a mobile app.

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

In 21st-century journalism, being completely debunked is no reason to drop the narrative.

As previously mentioned, there is much to object to in this recent Atlantic monthly piece "How Mars Will Be Policed" by Geoff Manaugh – – if I have the stomach for it, there is easily enough material here for a half dozen highly critical posts – – but perversely enough, it is the one really good part that best illustrates one of the worst aspects of modern journalism.

It is standard in medium to long form reporting, particularly in stories with a speculative or subjective element, to have an article that consists of a string of quotes from experts who are, if not in complete agreement, then are at least taking complementary positions. This chain is broken up by one or two dissenting voices who are completely ignored through the rest of the article.

Manaugh is nothing if not true to the form. Here is the relevant passage that occurs well into the piece.

It is difficult to overstate how effectively this point demolishes most of what has come before. It is completely reasonable to assume that, at least in the near future, any humans living or working on Mars will be constantly tracked. Barring some kind of hack or system failure, we would have a record of the exact position and vital signs of both perpetrator and victim of any crime on the planet. This doesn't preclude the possibility of robbery and murder on extraterrestrial bases, but it does effectively rule out the scenarios spelled out in the rest of the article.

One of the stranger and more malignant tenets of modern journalism is that simply mentioning a counter argument is sufficient for balance. You don't need to adjust your argument or explain why the criticism does not hold. In this case, Manaugh completely ignores the devastating main point, raises some weak and logically questionable objections (we'll go into the absurdity of the space roughnecks claim in another post), then goes back to his stories of mining camp murders and daring bank heists.

It is standard in medium to long form reporting, particularly in stories with a speculative or subjective element, to have an article that consists of a string of quotes from experts who are, if not in complete agreement, then are at least taking complementary positions. This chain is broken up by one or two dissenting voices who are completely ignored through the rest of the article.

Manaugh is nothing if not true to the form. Here is the relevant passage that occurs well into the piece.

For David Paige, worrying about crime on Mars is not just ahead of its time, it is unnecessary from the very beginning. Paige is a planetary scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), as well as a member of a team selected by NASA to design a ground-penetrating radar system for exploring the Martian subsurface. Crime on Mars, Paige told me, will be so difficult to execute that no one will be tempted to try.

“The issue,” Paige said, “is that there is going to be so much monitoring of people in various sorts of ways.” Airlocks will likely record exactly who opens them and when, for example, mapping everyone’s location down to precise times of day, even to the exact square feet of space they were standing in at a particular moment. Inhabitants’ vital signs, such as elevated heart rates and adrenaline levels, will also likely be recorded by sensors embedded in Martian clothing. If a crime was committed somewhere, time-stamped data could be correlated with a spatial record of where everyone was at that exact moment. “It’s going to be very easy to narrow down the possible culprits,” Paige suggested.

It is difficult to overstate how effectively this point demolishes most of what has come before. It is completely reasonable to assume that, at least in the near future, any humans living or working on Mars will be constantly tracked. Barring some kind of hack or system failure, we would have a record of the exact position and vital signs of both perpetrator and victim of any crime on the planet. This doesn't preclude the possibility of robbery and murder on extraterrestrial bases, but it does effectively rule out the scenarios spelled out in the rest of the article.

One of the stranger and more malignant tenets of modern journalism is that simply mentioning a counter argument is sufficient for balance. You don't need to adjust your argument or explain why the criticism does not hold. In this case, Manaugh completely ignores the devastating main point, raises some weak and logically questionable objections (we'll go into the absurdity of the space roughnecks claim in another post), then goes back to his stories of mining camp murders and daring bank heists.

Monday, October 1, 2018

Hiltzik's Musk/Trump post is looking pretty damned prescient right about now.

A couple of weeks ago, we discussed a Michael Hiltzik column that looked at some similarities between Donald Trump and Elon Musk and suggested that institutions which rely too heavily on charismatic but erratic con artists are likely to have extremely rude awakenings at some point.

Subsequent events have not undercut his thesis.

Tesla stock drops almost 14% as SEC tries to force Elon Musk out of company leadership

by Samantha Masunaga

Tesla Inc. stock closed sharply lower Friday as investors worried about a Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit that seeks to bar Elon Musk from continuing to lead the electric-car maker.

Shares of Tesla closed at $264.77, down 13.9% Friday afternoon.

The SEC filed its complaint against Musk after markets closed Thursday, alleging that the chairman and chief executive committed securities fraud by issuing a series of “false and misleading tweets about a potential transaction to take Tesla private.”

On Thursday evening, Tesla’s board of directors defended Musk, saying it is “fully confident in Elon, his integrity, and his leadership of the company, which has resulted in the most successful U.S. auto company in over a century.” It did not say what metric it was using for auto-company success.

[This is a good place to note that the LA Times, perhaps due to the influence of Hiltzik, was one of the first major news organizations to start seeing through the real life Tony Stark hype around Tesla – – MP]

Musk also issued a statement, calling the SEC lawsuit unjustified. “I have always taken action in the best interests of truth, transparency and investors,” he said.

The SEC complaint, which asks the court to ban Musk from running any public company, seeks a jury trial.

A request to bar an individual from serving as an officer or director of a public company is not unusual for SEC enforcement action, said Tom Gorman, a partner at law firm Dorsey & Whitney. But he believes a judge is unlikely to agree to force out Musk because of the likely impact it would have on Tesla, its workforce and shareholders.

“Mr. Musk is this company, in many ways,” Gorman said. “If you just say, ‘We’re not going to let you be an officer or director of a public company anymore,’ you could destroy the company and millions of dollars of shareholder value.”

...

Musk’s possible exit is likely one of the reasons Tesla’s stock fell the way it did, said David Whiston, stock analyst at Morningstar.

“Without Elon Musk, Tesla’s just an automaker that’s burning too much cash and has too much debt,” he said.

Of course, with Elon Musk, Tesla’s just an automaker that’s burning too much cash and has too much debt. Musk brings no special magic to this company he is extraordinarily gifted as a fundraiser, a promoter, and a motivational speaker, but he has shown absolutely no exceptional talent in any other area, especially engineering.

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Weekend Flashback

[The Brett Kavanaugh hearings have touched on a number of threads we've had running in the blog over the years, so I thought I'd repost a few relevant pieces just to keep them in the conversation.]

A key component of this experiment involved setting up radically different information streams for different target audiences. We talked about this before but one aspect that I've always wanted to address but never managed to get to is the way that this dual stream can explain seeming paradoxes in the radically different reactions of different groups of people to the same information.

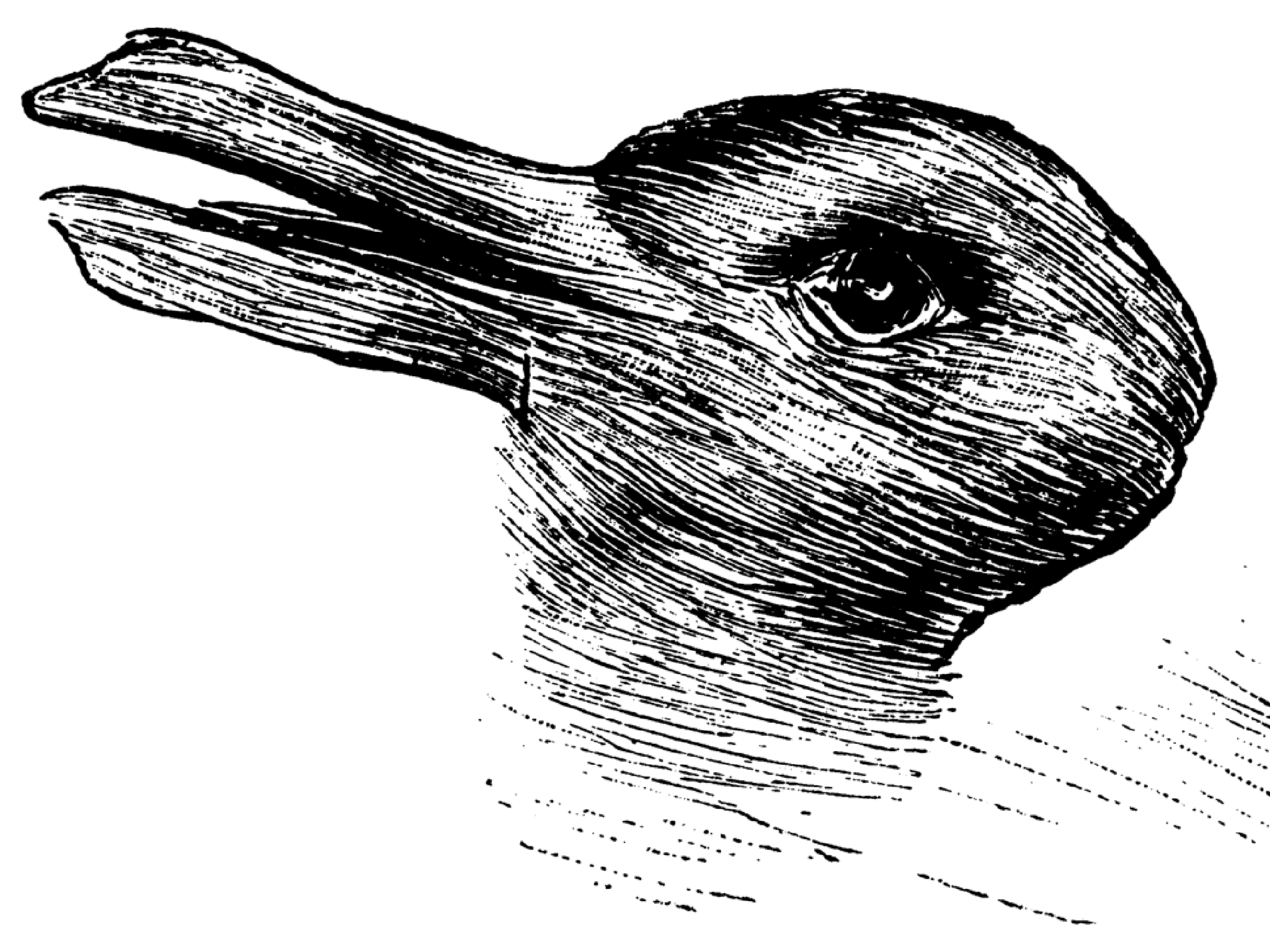

In order to get a handle on this, it might be useful to think back to that time in psych 101 when the professor brought out the ambiguous pictures.The standard example is the old woman and young woman (originally captioned in a cartoon as "my wife and my mother-in-law"). For the sake of variety, let's go with another.

The psych lecture would go something like this. Half the class was told to cover their eyes, the other half was shown a series of slides of birds. Then that half of the class was told to cover their eyes and the other half was shown a series of slides of small mammals. After being thus prepared, everyone looks at the following picture and is asked to write down what they see.

For the commentators who took the time to dig through the various media streams and put themselves in the place of each target audience (most notably Josh Marshall), it has been obvious for quite a while that those in the right-wing media bubble have a strong tendency to interpret events in a way that is consistent with the information, framing and narratives of the bubble. Donald Trump succeeded in the primaries because both his arguments and his affect seemed reasonable in the context of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh.

I'll come back and fill in some more details later but, as much as I want to avoid oversimplifying, this really is pretty simple. The journalists who have come off as sharp and ahead of the curve, have all (as far as I can tell) looked seriously at right-wing media and have asked themselves, if I actually believed everything I just heard, how would I react to the different candidates and their proposals?

This begs loads of questions and I don't want to oversell the explanatory power here, but given all of the overheated rhetoric about how chaotic and unpredictable this election has been, it's worth noting when those getting it right have something in common.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Rabbit season! Duck season! Rabbit season!

I'm planning on coming back and elaborating more on this later, but, as frequently noted here and elsewhere, while most commentators have fared extraordinarily poorly over the past year, a handful (including, yes, your not-so-humble hosts) have had a good run. Though they may not have framed it in exactly these terms, pretty much everybody who has gotten it mostly right has approached the election as the final stages of a massive social engineering experiment conducted by the conservative movement.A key component of this experiment involved setting up radically different information streams for different target audiences. We talked about this before but one aspect that I've always wanted to address but never managed to get to is the way that this dual stream can explain seeming paradoxes in the radically different reactions of different groups of people to the same information.

In order to get a handle on this, it might be useful to think back to that time in psych 101 when the professor brought out the ambiguous pictures.The standard example is the old woman and young woman (originally captioned in a cartoon as "my wife and my mother-in-law"). For the sake of variety, let's go with another.

The psych lecture would go something like this. Half the class was told to cover their eyes, the other half was shown a series of slides of birds. Then that half of the class was told to cover their eyes and the other half was shown a series of slides of small mammals. After being thus prepared, everyone looks at the following picture and is asked to write down what they see.

For the commentators who took the time to dig through the various media streams and put themselves in the place of each target audience (most notably Josh Marshall), it has been obvious for quite a while that those in the right-wing media bubble have a strong tendency to interpret events in a way that is consistent with the information, framing and narratives of the bubble. Donald Trump succeeded in the primaries because both his arguments and his affect seemed reasonable in the context of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh.

I'll come back and fill in some more details later but, as much as I want to avoid oversimplifying, this really is pretty simple. The journalists who have come off as sharp and ahead of the curve, have all (as far as I can tell) looked seriously at right-wing media and have asked themselves, if I actually believed everything I just heard, how would I react to the different candidates and their proposals?

This begs loads of questions and I don't want to oversell the explanatory power here, but given all of the overheated rhetoric about how chaotic and unpredictable this election has been, it's worth noting when those getting it right have something in common.

Friday, September 28, 2018

Atomic airplanes and Kodachrome moments.

If was the sister publication to Galaxy Magazine, a bit less prestigious, but still well-respected and catering to the same hard-science audience. This 1957 issue brings up a couple of interesting points for our postwar technological expectations thread.

One is that, at least in the popular press, there was a widespread assumption in the 1950s that nuclear energy would come to play a large role in aerospace in the next few decades.. I'm not sure to what extent actual researchers in the field shared these expectations, but it is safe to say that the young science nerds of 1958 would be somewhat disappointed at how little much of the technology has changed.

Another thing that pops out from a 2018 perspective is the reference to Kodachrome on the cover. The idea that Kodak film would be used to document the first Mars expedition seems rather amusing in retrospect, though I'm not sure exactly where the art director.it wrong. Was he assuming that the iconic company would still be around well into the 21st century or did he believe we make it to Mars in the 20th?

One is that, at least in the popular press, there was a widespread assumption in the 1950s that nuclear energy would come to play a large role in aerospace in the next few decades.. I'm not sure to what extent actual researchers in the field shared these expectations, but it is safe to say that the young science nerds of 1958 would be somewhat disappointed at how little much of the technology has changed.

Another thing that pops out from a 2018 perspective is the reference to Kodachrome on the cover. The idea that Kodak film would be used to document the first Mars expedition seems rather amusing in retrospect, though I'm not sure exactly where the art director.it wrong. Was he assuming that the iconic company would still be around well into the 21st century or did he believe we make it to Mars in the 20th?

Thursday, September 27, 2018

"I aim at the stars, but sometimes I hit London."

While reading up on public perceptions of the space race during the postwar era, I was disappointed to learn that my favorite Mort Sahl line wasn't actually from Mort Sahl.

Satirist Mort Sahl has been credited with mocking von Braun by saying "I aim at the stars, but sometimes I hit London."[39] In fact that line appears in the film I Aim at the Stars, a 1960 biopic of von Braun.Thank God we still have Lehrer.

"Wernher von Braun" (1965): A song written and performed by Tom Lehrer for an episode of NBC's American version of the BBC TV show That Was The Week That Was; the song was later included in Lehrer's albums That Was The Year That Was and The Remains of Tom Lehrer. It was a satire on what some saw as von Braun's cavalier attitude toward the consequences of his work in Nazi Germany

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

Ley on the pre-history of the space station

This 1953 piece by Willy Ley is interesting for any number of reasons, but there are a couple that are especially relevant to our recent threads.

First, there's the comparison of technologies that seem to catch everyone off guard compared with those that have a long history of antecedents in fiction/myth, serious speculation, and failed experiments before becoming viable. It can be difficult to sort these out from a modern perspective, so it is extremely useful to have the topic explored by someone like Ley who combines mastery of the science with extensive knowledge of the fiction.

Second, and even more applicable to our ongoing conversation, is the timeframe. As with many concepts in space travel, the idea of a space station was for all practical intents and purposes introduced by Hermann Oberth 30 years before the appearance of the following article. Within around a quarter of a century, scientists had developed the design into what we still think of today when we hear the words space station, a torus-shaped orbital platform where people and cargo from surface-launched rockets could be transferred to long-range spacecrafts.

This is very much consistent with the push into space of the period in particular and of the postwar science and tech spike in general. Most of the enabling technologies were either truly cutting-edge (like atomic power and transistors) or were developed during or between the two world wars.

By comparison, at least when it comes to 21st-century aerospace, the basic ideas behind most of our highly touted advances and "bold and visionary" proposals tend to be much older, often passing the 50 or even 60 year mark. This is not to say that impressive work is not being done or that major technical challenges are not being overcome, but the role of the cutting-edge and even the moderately recent discovery is far less than it used to be, and that might not be a good sign.

First, there's the comparison of technologies that seem to catch everyone off guard compared with those that have a long history of antecedents in fiction/myth, serious speculation, and failed experiments before becoming viable. It can be difficult to sort these out from a modern perspective, so it is extremely useful to have the topic explored by someone like Ley who combines mastery of the science with extensive knowledge of the fiction.

Second, and even more applicable to our ongoing conversation, is the timeframe. As with many concepts in space travel, the idea of a space station was for all practical intents and purposes introduced by Hermann Oberth 30 years before the appearance of the following article. Within around a quarter of a century, scientists had developed the design into what we still think of today when we hear the words space station, a torus-shaped orbital platform where people and cargo from surface-launched rockets could be transferred to long-range spacecrafts.

This is very much consistent with the push into space of the period in particular and of the postwar science and tech spike in general. Most of the enabling technologies were either truly cutting-edge (like atomic power and transistors) or were developed during or between the two world wars.

By comparison, at least when it comes to 21st-century aerospace, the basic ideas behind most of our highly touted advances and "bold and visionary" proposals tend to be much older, often passing the 50 or even 60 year mark. This is not to say that impressive work is not being done or that major technical challenges are not being overcome, but the role of the cutting-edge and even the moderately recent discovery is far less than it used to be, and that might not be a good sign.

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Or you could have just taken away the bullets

I have all sorts of problems with this Atlantic piece [How Mars Will Be Policed by Geoff Manaugh] but before I get into those big complaints, there is a smaller point that bothers me.

First off, I wonder if this really happen. It's told in an apocryphal, urban-legend style that makes me somewhat skeptical. More to the point, I'm trying to think of what dire emergency which was likely to occur in an Antarctic research base would require a gun of any kind. It's hard to imagine what external threats they might have been worried about and the "let's have a gun around in case someone goes crazy" theory has one of those flaws that you'd like to think smart people would catch in the planning stage.

If it didn't happen, there is an obvious problem with it being presented as fact, but if it did happen, there is almost as great a problem with the lack of identifying information or collaborating detail. Has anyone out there heard this story before?

When I asked Kim Stanley Robinson—whose award-winning Mars Trilogy imagines the human settlement of the Red Planet in extraordinary detail—about the future of police activity on Mars, he responded with a story. In the 1980s, he told me, a team from the National Science Foundation was sent to a research base in Antarctica with a single handgun for the entire crew. The gun was intended as a tool of last resort, for only the most dire of emergencies, but the scientists felt its potential for abuse was too serious to remain unchecked. According to Robinson, they dismantled the gun into three constituent parts and stored each piece with a different caretaker. That way, if someone got drunk and flew into a rage, or simply cracked under the loneliness and pressure, there would be no realistic scenario in which anyone could collect the separate pieces, reassemble the gun, load it, and begin holding people hostage (or worse).

First off, I wonder if this really happen. It's told in an apocryphal, urban-legend style that makes me somewhat skeptical. More to the point, I'm trying to think of what dire emergency which was likely to occur in an Antarctic research base would require a gun of any kind. It's hard to imagine what external threats they might have been worried about and the "let's have a gun around in case someone goes crazy" theory has one of those flaws that you'd like to think smart people would catch in the planning stage.

If it didn't happen, there is an obvious problem with it being presented as fact, but if it did happen, there is almost as great a problem with the lack of identifying information or collaborating detail. Has anyone out there heard this story before?

Monday, September 24, 2018

On the plus side, the von Braun and Ley Zeppelin designs would make for some very cool steam-punk art

Sometimes, when wandering over what should be well explored territory you come across a pair of familiar facts that suddenly strike you as strange or even shocking when considered together.

I had one of those moments yesterday when thinking about our vanity aerospace thread, and specifically its relationship to the science-fiction and popular science writing of the postwar era. As previously mentioned, most of the "bold" and "visionary" proposals coming from billionaires like Paul Allen, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are almost all similar and in some cases all but identical to the ideas being laid out by people like Werner von Braun and Willy Ley more than 60 years ago.

That alone is striking – – these are visions of the future are often older than the people making them – – but the full impact didn't hit me until I got to thinking about what looking back 60 or 70 years would've been like back when von Braun and Ley were first laying these ideas out for the public in popular magazine articles and Disney TV specials.

Take a minute to think about the technological gap between the world of the early 1950s and that of the late 1880s. The rocket scientists and their popularizers were discussing multistage rockets, radio communication and control, atomic energy. In the 1880s these subjects were, at best, the subject of speculation. In some cases, even the underlying physics was yet to be established.

When people in the 1950s looked back at how their grandparents imagine the future, the ideas seemed primitive and charmingly quaint. When we look back over a comparable interval, we see a view of the future which looks, or lack of a better word, futuristic. For me, at least, that's a rather depressing thought.

I had one of those moments yesterday when thinking about our vanity aerospace thread, and specifically its relationship to the science-fiction and popular science writing of the postwar era. As previously mentioned, most of the "bold" and "visionary" proposals coming from billionaires like Paul Allen, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are almost all similar and in some cases all but identical to the ideas being laid out by people like Werner von Braun and Willy Ley more than 60 years ago.

That alone is striking – – these are visions of the future are often older than the people making them – – but the full impact didn't hit me until I got to thinking about what looking back 60 or 70 years would've been like back when von Braun and Ley were first laying these ideas out for the public in popular magazine articles and Disney TV specials.

Take a minute to think about the technological gap between the world of the early 1950s and that of the late 1880s. The rocket scientists and their popularizers were discussing multistage rockets, radio communication and control, atomic energy. In the 1880s these subjects were, at best, the subject of speculation. In some cases, even the underlying physics was yet to be established.

When people in the 1950s looked back at how their grandparents imagine the future, the ideas seemed primitive and charmingly quaint. When we look back over a comparable interval, we see a view of the future which looks, or lack of a better word, futuristic. For me, at least, that's a rather depressing thought.

Friday, September 21, 2018

Fly me near the moon...

This isn't really that big of a story – – a remounting of something we did 50 years ago only with some of the most difficult parts left out. That said, you can argue that anything that increases interest in space travel should be chalked up on the plus side. Besides, it's easily the least embarrassing Elon Musk news we've seen in quite a while.

It is also important to note that Musk doesn't the best record with timelines and other details, so the statement "could be ready to launch in just five years" should be judged accordingly.

I apologize for passing over the obvious video accompaniments to this post. Instead, here are some songs from Tony Bennett that stand up better and offer such talented collaborators as Diana Krall and Count Basie.

A Japanese billionaire and a coterie of artists will visit the moon as early as 2023, becoming the first private citizens ever to fly beyond low Earth orbit, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced tonight.

Yusaku Maezawa, the founder of Japanese e-commerce giant Zozo, has signed up to fly a round-the-moon mission aboard SpaceX's BFR spaceship-rocket combo, he and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced during a webcast tonight (Sept. 17) from the company's rocket factory in Hawthorne, California.

The mission — which will loop around, but not land on, the moon — could be ready to launch in just five years, Musk said.

It is also important to note that Musk doesn't the best record with timelines and other details, so the statement "could be ready to launch in just five years" should be judged accordingly.

I apologize for passing over the obvious video accompaniments to this post. Instead, here are some songs from Tony Bennett that stand up better and offer such talented collaborators as Diana Krall and Count Basie.

Thursday, September 20, 2018

Poetic economics

I've noticed the rise of a certain kind of proposal that makes little sense in terms of efficiency he, and resource utilization, but which makes a great deal of what we might call aesthetic sense.

Take, for instance, the plan that got a great deal of traction a few years ago for charging batteries in the Third World with special high-tech soccer balls which converted kinetic energy into electricity. It was unsurprisingly a complete disaster, a needlessly complicated and expensive "solution" to a problem that was better solved through a number of other well established approaches. It offered no discernible advantages and many serious drawbacks.

It did, however, have an unquestionable appeal. The image of children playing and at the same time using cutting-edge technology to power their way into 21st century media access felt like something bright and forward-looking. The fact that it made no practical sense didn't matter; it made aesthetic sense.

Likewise, this much discussed proposal to convert sequestered carbon into fuel has an unquestionable poetic symmetry about it, not only solving the tremendous environmental problems caused by burning fossil fuels, but actually going full circle and using that unwanted carbon as a replacement for those fuels. From a practical standpoint, though, it is difficult to see the rationale for using the considerable energy required to extract the carbon from carbon dioxide and the hydrogen from water (don't know much about physics but I'm pretty sure the laws of thermodynamics kick in somewhere here) all so we can take the carbon and change it back into atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Even if we can't find some other use for it (like this), we can always bury the carbon, in effect putting it back where it was before it caused the damage. From an environmental sense, it makes more sense to bury it than to burn it, but that doesn't make for nearly as good a story.

Take, for instance, the plan that got a great deal of traction a few years ago for charging batteries in the Third World with special high-tech soccer balls which converted kinetic energy into electricity. It was unsurprisingly a complete disaster, a needlessly complicated and expensive "solution" to a problem that was better solved through a number of other well established approaches. It offered no discernible advantages and many serious drawbacks.

It did, however, have an unquestionable appeal. The image of children playing and at the same time using cutting-edge technology to power their way into 21st century media access felt like something bright and forward-looking. The fact that it made no practical sense didn't matter; it made aesthetic sense.

Likewise, this much discussed proposal to convert sequestered carbon into fuel has an unquestionable poetic symmetry about it, not only solving the tremendous environmental problems caused by burning fossil fuels, but actually going full circle and using that unwanted carbon as a replacement for those fuels. From a practical standpoint, though, it is difficult to see the rationale for using the considerable energy required to extract the carbon from carbon dioxide and the hydrogen from water (don't know much about physics but I'm pretty sure the laws of thermodynamics kick in somewhere here) all so we can take the carbon and change it back into atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Even if we can't find some other use for it (like this), we can always bury the carbon, in effect putting it back where it was before it caused the damage. From an environmental sense, it makes more sense to bury it than to burn it, but that doesn't make for nearly as good a story.

Wednesday, September 19, 2018

If. Only.

Lots of bloggers know that you can find tons of cool retro-future art (all in the public domain) in the Internet Archive's Galaxy Magazine collection. Far fewer seem to know about its sister publication, If, which is a shame.

From Wikipedia

The magazine was moderately successful, though it was never considered to be in the first tier of science-fiction magazines. It achieved its greatest success under editor Frederik Pohl, winning the Hugo Award for best professional magazine three years running from 1966 to 1968. If published many award-winning stories over its 22 years, including Robert A. Heinlein's novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress and Harlan Ellison's short story "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream". The most prominent writer to make his first sale to If was Larry Niven, whose story "The Coldest Place" appeared in the December 1964 issue.

Pohl paid one cent per word for the stories he bought for If, whereas Galaxy paid three cents per word, and like Gold, he regarded Galaxy as the leading magazine of the two, whereas If was somewhere he could work with new writers, and try experiments and whims. This developed into a selling point when a letter from a reader, Clayton Hamlin, prompted Pohl to declare that he would publish a new writer in every single issue of the magazine,[14][15] though he was also able to attract well-known writers.[16] When Pohl began his stint as editor, both magazines were operating at a loss; despite If's lower budget, Pohl found it more fun to edit, and commented that apparently the readers thought so, too; he was able to make If show a profit before Galaxy, adding, "What was fun for me seemed to be fun for them."

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

The nurturing of absurdity

There are a wealth of recent examples of arguments and interpretations that, despite being obviously absurd, not only make their way into the popular discourse, but actually become dominant conventional wisdom. Though here at the blog, we've been focused primarily on examples from science, technology, and business, some of the best examples come from mainstream media's political commentary. This isn't to say you can't find as bad or worse in conservative media – – quite the opposite – – but those absurdities are reliably in the service of a partisan agenda. The reasons for institutions like NPR making bullshit the default setting in these cases are more subtle.

The most notable recent example is the Trump base pseudo-paradox. This is actually something of a twofer. It starts with experienced and supposedly savvy analysts expressing amazement over Trump taking some offensive stance and yet holding his base, then the analysts conclude that this spells trouble for the Democrats.

Both parts collapsed under scrutiny. Those offensive policies and statements are (with a few exceptions) popular with core supporters and deeply unpopular with the rest of the country. Trump is in a sense pandering twice to his base here, not only agreeing with them on controversy of issues, but hammering home the point that, by doing so, he is siding with his supporters over everyone else. Paranoia and persecution have long been major components of conservative culture and the rise of conservative media has aggressively and deliberately cultivated those feelings.

Thus, Trump holding on to his base is possibly the most explicable development of the past few years, and it shows no special political genius on his part. Anyone can maintain a grip on supporters by taking their side even when the rest of the country strongly opposes them. The only reason you don't see this done more often is because winning the approval of the 25 to 35% of the country that was going to vote for you anyway while angering and energizing 60 to 70% of the country is that it's a disastrous strategy. Think Goldwater but more extreme.

So how did these points not just persist but become ubiquitous? When you put this together with all the other recent examples of the obviously untrue making its way into the conventional wisdom, the inescapable answer is that plausibility doesn't rank that high. If something complements a safe standard narrative (in this case the Dems in disarray), the fact that it doesn't actually make much sense can be overlooked, particularly when you factor in convergent thinking and the inability of many in the world of commentary to think in terms of appropriate levels of aggregation.

The most notable recent example is the Trump base pseudo-paradox. This is actually something of a twofer. It starts with experienced and supposedly savvy analysts expressing amazement over Trump taking some offensive stance and yet holding his base, then the analysts conclude that this spells trouble for the Democrats.

Both parts collapsed under scrutiny. Those offensive policies and statements are (with a few exceptions) popular with core supporters and deeply unpopular with the rest of the country. Trump is in a sense pandering twice to his base here, not only agreeing with them on controversy of issues, but hammering home the point that, by doing so, he is siding with his supporters over everyone else. Paranoia and persecution have long been major components of conservative culture and the rise of conservative media has aggressively and deliberately cultivated those feelings.

Thus, Trump holding on to his base is possibly the most explicable development of the past few years, and it shows no special political genius on his part. Anyone can maintain a grip on supporters by taking their side even when the rest of the country strongly opposes them. The only reason you don't see this done more often is because winning the approval of the 25 to 35% of the country that was going to vote for you anyway while angering and energizing 60 to 70% of the country is that it's a disastrous strategy. Think Goldwater but more extreme.

So how did these points not just persist but become ubiquitous? When you put this together with all the other recent examples of the obviously untrue making its way into the conventional wisdom, the inescapable answer is that plausibility doesn't rank that high. If something complements a safe standard narrative (in this case the Dems in disarray), the fact that it doesn't actually make much sense can be overlooked, particularly when you factor in convergent thinking and the inability of many in the world of commentary to think in terms of appropriate levels of aggregation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)