A number of times over the past few years, Andrew Gelman has revisited this Marginal Revolution post from Alex Tabarrok. (emphasis added.)

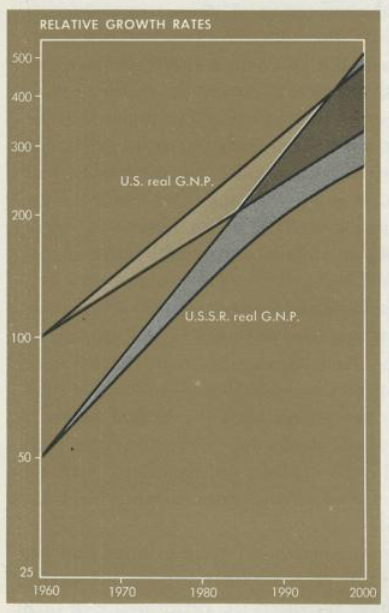

In the 1961 edition of his famous textbook of economic principles, Paul Samuelson wrote that GNP in the Soviet Union was about half that in the United States but the Soviet Union was growing faster. As a result, one could comfortably forecast that Soviet GNP would exceed that of the United States by as early as 1984 or perhaps by as late as 1997 and in any event Soviet GNP would greatly catch-up to U.S. GNP. A poor forecast–but it gets worse because in subsequent editions Samuelson presented the same analysis again and again except the overtaking time was always pushed further into the future so by 1980 the dates were 2002 to 2012. In subsequent editions, Samuelson provided no acknowledgment of his past failure to predict and little commentary beyond remarks about “bad weather” in the Soviet Union (see Levy and Peart for more details).

I've always had the nagging feeling that this was not the whole story, a reaction I often have with Marginal Revolution posts, but it wasn't until recently that I came across this very good Paul Krugman piece discussing how the collapse of the Soviet economy helped put Vladimir Putin in power that I found out what Tabarrok had left out.

First, some background: Nowadays everyone views the old Soviet Union, with its centrally planned economy, as an abject failure. But it didn’t always look that way. Indeed, in the 1950s, and even into the 1960s, many people around the world saw Soviet economic development as a success story; a backward nation had transformed itself into a major world power. (Killing millions in the process, but who’s counting?) As late as 1970, the Soviet Union’s success in converging toward Western levels of wealth seemed second only to Japan’s.

Nor was this a statistical mirage. If nothing else, Soviet performance during World War II demonstrated that its industrial growth under Joseph Stalin had been very real.

After 1970, however, the Soviet growth story fell apart, and by some measures technological progress came to a standstill.

If you follow the link to the Robert C. Allen paper, you'll find the following graph:

Assuming that the US was one of the boxes on the far right, when "Paul Samuelson wrote that GNP in the Soviet Union was about half that in the United States but the Soviet Union was growing faster," he was simply stating the facts.

To be clear, I didn't know any of these things about the economy of mid 20th century USSR. The only reason I started to look into it was because I happened to read the Krugman op-ed. Before that my knowledge was be limited to the memory of some disastrous famines and a few anecdotes about Soviet factories turning out concrete couches, and I would have had no idea that Samuelson's models were consistent with the actual GDP/GNP data.

Quick caveat. Neither GDP nor GNP is a measure of quality of life. The Soviet Union was a terrible place. As Krugman points out, Stalin's policies killed millions of his own people. We should also note that economies are complex things that can never truly be boiled down to a single scalar. The same country that could build the world's second most powerful military could also be comically inept at making consumer goods and tragically bad at producing food.

But this is a conversation about growth, and given those terms, there are three great unresolved questions about the Soviet economy. Why was growth so good for forty plus years? Why was it so stunningly bad after that? And what changed?

This opens up multiple really big warehouse-store cans of peas, but if we keep focused on the question of Samuelson's treatment of the Soviet economy, it certainly looks reasonable up to say the late 60s or early seventies. After that, the performance of the Soviet economy started to rapidly collapse. What exactly do we expect a modeler to do under those circumstances? The first option is to treat the new numbers as an outlier. The second is to treat them as a trend. The third is to attempt to incorporate the new data while still not ignoring the bulk of the numbers. It appears that Samuelson went with door number three which would seem to be the most reasonable choice.

There were certainly issues with Samuelson's approach. Ironically, by editing out the genuinely impressive and largely

uncontroversial period of Soviet economic growth, Tabarrok missed the chance to

point out a real and fairly obvious flaw in Samuelson's forecast. Small

economies modernizing often rack up impressive growth rates but they by nature follow S curves. You can create a big bump in GDP by moving a

peasant or surf from the fields to the factory, but you can only do it

once.Linear extrapolation was clearly a mistake.

In general, though, if you start with the fact that the observed data included a 40 plus year run of extremely high GDP growth, then look at where the data was at the point in time when Samuelson made a particular statement or assertion (taking into account a one or two year time lag between the analyses being run and the copyright date on the textbook), most of it looks okay. Were there changes that should have come one edition before? Sure, but the impression of clownishness which the George Mason crowd is pushing here only works if the audience doesn't know the history of Soviet economic growth, but does know how the USSR ended up. Taking all of that into account, Samuelson comes off looking not all that bad. Alex Tabarrok, on the other hand...

No comments:

Post a Comment