By digging into the rich history of board games (and possibly doing a little tweaking) I suspect we can come up with other abstract strategy games of perfect information that put humans and machines on a more equal footing, and more importantly, provide as or more interesting fields of study for AI. Of course, there's always go, but wouldn't it be fun to do something different for a change?

Whenever you need to make a survey of games, the best place to start is almost always David Parlett (followed by Sid Sackson but more on that later). Lots of promising potential candidates both historical and modern. To get things started, how about the medieval game that for a while rivaled chess for popularity, rithmomachy?

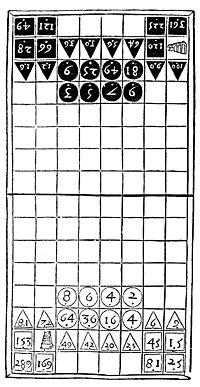

From Wikipedia.

Very little, if anything, is known about the origin of the game. But it is known that medieval writers attributed it to Pythagoras, although no trace of it has been discovered in Greek literature, and the earliest mention of it is from the time of Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054).

The name, which appears in a variety of forms, points to a Greek origin, the more so because Greek was little known at the time when the game first appeared in literature. Based upon the Greek theory of numbers, and having a Greek name, it is still speculated by some that the origin of the game is to be sought in the Greek civilization, and perhaps in the later schools of Byzantium or Alexandria.

The first written evidence of Rithmomachia dates back to around 1030, when a monk, named Asilo, created a game that illustrated the number theory of Boëthius' De institutione arithmetica, for the students of monastery schools. The rules of the game were improved shortly thereafter by the respected monk, Hermannus Contractus, from Reichenau, and in the school of Liège. In the following centuries, Rithmomachia spread quickly through schools and monasteries in the southern parts of Germany and France. It was used mainly as a teaching aid, but, gradually, intellectuals started to play it for pleasure. In the 13th century Rithmomachia came to England, where famous mathematician Thomas Bradwardine wrote a text about it. Even Roger Bacon recommended Rithmomachia to his students, while Sir Thomas More let the inhabitants of the fictitious Utopia play it for recreation.

The game was well enough known as to justify printed treatises in Latin, French, Italian, and German, in the sixteenth century, and to have public advertisements of the sale of the board and pieces under the shadow of the old Sorbonne.

Any other suggestions?

Hnefatafl - a viking game in which one player tries to move a king from the center to the edge of the board while the other player attempts to surround it.

ReplyDeleteI used it for a cognitive psychology research project which examined how people's knowledge of rules affected memory for board positions without knowledge of strategy or extensive play experience.

I've toyed with the idea of doing some AI work using simpler games and had considered Stephen Sniderman's Order and Chaos. It seems the game may have been solved last year, but it could still be a test case to compare learning algorithms.

I was familiar with Hnefatafl from David Parlett's Oxford History, but I've never seen it played. It does seem interesting.

DeleteYou bring up another point that I perhaps should have in the original post. New-to-the-user games like Hnefatafl, agon, and, yes, Kruzno would perfectly lend themselves to psychological research on learning processes, problem-solving and strategic thinking. With a more familiar games such as chess, experiment subjects walk in the door with a wide range of previous experience and instruction. With something like Hnefatafl, you can get a much cleaner read because everyone is starting from roughly the same page.