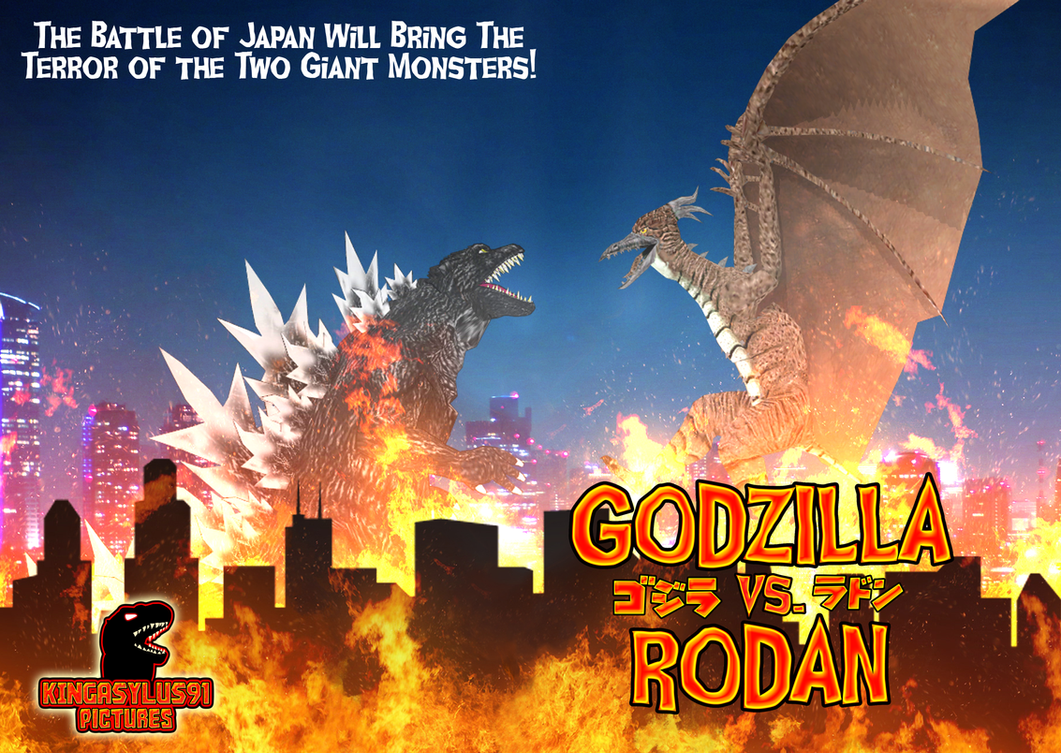

When giant, hideous monsters clash it's difficult deciding who to root for.

Questions of team loyalty aside, this Slate article by Will Oremus raises interesting questions about attitudes toward and incentives for copyright infringement.

Last year on his podcast Hello Internet, the Australian filmmaker Brady Haran coined the term freebooting to describe the act of taking someone’s YouTube video and re-uploading it on a different platform for your own benefit....That caveat might be worth a post of it own on apples-to-oranges data comparisons. Maybe next time

Unlike sea pirates, Facebook freebooters don’t directly profit from their plundering. That’s because, unlike YouTube, Facebook doesn’t run commercials before its native videos—not yet, at least. That’s part of why they spread like wildfire. What the freebooter gains is attention, whether in the form of likes, shares, or new followers for its Facebook page. That can be valuable, sure, especially for brands and media outlets. But it might seem like a relatively small booty compared with the legal risk involved. Sandlin’s lawyer, Stephen Heninger, told me he believes Facebook freebooting amounts to copyright infringement, though he also said the phenomenon is new enough that the legal precedent is limited.

...

Freebooting, to be clear, is not the same as simply sharing a link to someone’s YouTube video on Facebook. When you do that, Facebook embeds the YouTube video, and all the views—and advertising revenues—are properly credited to its original publisher. No one has a problem with that, including Sandlin. It’s how the system is supposed to work.

But it doesn’t work that way anymore—not well, anyway. That’s because, over the past year, Facebook has decided it’s no longer content to be a venue for sharing links to articles and videos found elsewhere on the Internet. Facebook now wants to host the content itself—and, in so doing, control the advertising revenue that flows from it....

To that end, Facebook has built its own video platform and given it a decisive home-field advantage in the News Feed. Share a YouTube video on Facebook, and it will appear in your friends’ feeds as a small, static preview image with a “play” button on it—that is, if it appears in your friends’ News Feeds at all. Those who do see it will be hesitant to click on it, because they know it’s likely to be preceded by an ad. But take that same video and upload it directly to Facebook, and it will appear in your friends’ feeds as a full-size video that starts playing automatically as they scroll past it. (That’s less annoying than it sounds.) Oh, and it will appear in a lot of your friends’ feeds. Anecdotal evidence—and guidance from Facebook itself—suggests native videos perform orders of magnitude better on Facebook than those shared from other platforms.

Facebook’s video push has produced stunning results. In September, the company announced that its users were watching 1 billion videos a day on the social network. By April, that number had quadrupled to 4 billion. An in-depth Fortune story in June on “Facebook’s Video-Traffic Explosion” reported that publishers such as BuzzFeed have seen their Facebook video views grow tenfold in the past year. One caveat is that a view of a Facebook video might not mean quite the same thing as a view of a YouTube video, because Facebook videos play in your feed whether you click on them or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment