While the gift-giving season is still upon us...

Back when I was teaching high school math, I got very much into games and puzzles as a way of teaching both specific concepts and more general skills like problem-solving and strategic thinking. In addition to all the standards (chess, checkers, etc.) and some interesting historical games, I started developing some of my own, mostly played on 6 x 6 x 6 hexagonal boards that I printed out and taped together.

I was particularly happy with the way one of these games, Kružno, turned out. It played well. The underlying dynamics were, as far as I could tell, unique, and it was what I like to call an elegant game, with very simple rules (it takes a bright seven-year-old about five minutes to catch on) supporting a reasonably high level of complexity and challenging play.

I ran off a small batch and tried my hand at selling them both individually and as part of a hexagonal game set (the 6 x 6 x 6 board can be used for dozens of contemporary and historical games). I sold a few and got some good feed back but realized I didn't have the risk-tolerance to take the business to the next level.

I've been working on an online Kružno. The logic's been worked out and I'm planning on getting it up and running next year. In the meantime, I'll keep the Amazon store up for a while longer. Check it out. I think you'll have fun with it.

* No, really.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

As if you didn't have enough to worry about

[This is another one of those too-topical-to-ignore topics that I don't have nearly enough time to do justice to, but I suppose that's why God invented blogging.]

There's a huge problem that people aren't talking about nearly enough. More troublingly, when it does get discussed, it is usually treated as a series of unrelated problems, much like a cocaine addict who complains about his drug problem, bankruptcy, divorce, and encounters with loan sharks, but who never makes a causal connection between the items on the list.

Think about all of the recent news stories that are about or are a result of concentration/deregulation of media power and the inevitable consequences. Obviously, net neutrality falls under this category. So does the role that Facebook, and, to a lesser extent, Twitter played in the misinformation that influenced the 2016 election. The role of the platform monopolies in the ongoing implosion of digital journalism has been widely discussed by commentators like Josh Marshall. The Time Warner/AT&T merger has gotten coverage primarily due to the ethically questionable involvement of Donald Trump, with very little being said about the numerous other concerns. Outside of a few fan boys excited over the possibility of seeing the X-Men fight the Avengers, almost no one's talking about Disney's Fox acquisition.

It didn't used to be like this. For most of the 20th century, the government kept a vigilant watch for even potential accumulation of media power. Ownership was restricted. Movie studios were forced to sell their theaters (see United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc). The largest radio network was effectively forced to split in two (that's why we have ABC broadcasting today). Media companies were tightly regulated, their workforce was heavily unionized, and they were forced to jump through all manner of hoops before expanding into new markets to insure that the public good was being served.

In short, the companies were subjected to conditions which we have been told prevent growth, stifle innovation, and kill jobs. We can never know what would've happened had the government given these companies a freer hand but we can say with certainty that for media, the Post-war era was a period of explosive growth, fantastic advances, and incredible successes both economically and culturally. It's worth noting that the biggest entertainment franchises of the market-worshiping, anything-goes 21st century were mostly created under the yoke of 20th century regulation.

Monday, December 18, 2017

Our annual Toys-for-Tots post

[running late this year but there's still time]

A good Christmas can do a lot to take the edge off of a bad year both for children and their parents (and a lot of families are having a bad year). It's the season to pick up a few toys, drop them by the fire station and make some people feel good about themselves during what can be one of the toughest times of the year.

If you're new to the Toys-for-Tots concept, here are the rules I normally use when shopping:

The gifts should be nice enough to sit alone under a tree. The child who gets nothing else should still feel that he or she had a special Christmas. A large stuffed animal, a big metal truck, a large can of Legos with enough pieces to keep up with an active imagination. You can get any of these for around twenty or thirty bucks at Wal-Mart or Costco;*

Shop smart. The better the deals the more toys can go in your cart;

No batteries. (I'm a strong believer in kid power);**

Speaking of kid power, it's impossible to be sedentary while playing with a basketball;

No toys that need lots of accessories;

For games, you're generally better off going with a classic;

No movie or TV show tie-ins. (This one's kind of a personal quirk and I will make some exceptions like Sesame Street);

Look for something durable. These will have to last;

For smaller children, you really can't beat Fisher Price and PlaySkool. Both companies have mastered the art of coming up with cleverly designed toys that children love and that will stand up to generations of energetic and creative play.

*I previously used Target here, but their selection has been dropping over the past few years and it's gotten more difficult to find toys that meet my criteria.

** I'd like to soften this position just bit. It's okay for a toy to use batteries, just not to need them. Fisher Price and PlaySkool have both gotten into the habit of adding lights and sounds to classic toys, but when the batteries die, the toys live on, still powered by the energy of children at play.

Friday, December 15, 2017

Megan McArdle is worth reading today

This is Joseph

I want too outsource today's comments to Megan McArdle. I don't agree with everything in her piece, but I think that she highlights the consequences of not working out due process for these issues. The real underlying issue, which I think that she omits, is that powerful people have been protected by position of great privilege from facing the consequences of loathsome behavior. That has led to some justifiable rage, after years of torment and this needs to be thoughtfully considered. But let's make sure that the path forward is developed on solid ground, because it would be a pity for this forward progress to be lost.

I want too outsource today's comments to Megan McArdle. I don't agree with everything in her piece, but I think that she highlights the consequences of not working out due process for these issues. The real underlying issue, which I think that she omits, is that powerful people have been protected by position of great privilege from facing the consequences of loathsome behavior. That has led to some justifiable rage, after years of torment and this needs to be thoughtfully considered. But let's make sure that the path forward is developed on solid ground, because it would be a pity for this forward progress to be lost.

"All that lava rushing 'round the corner" – – A musical accompaniment for the post-Moore GOP mood

We've been hearing a lot about growing Republican anxiety over a possible electoral "tsunami" in 2018. Without getting into the likelihood of this particular scenario, I would like to suggest a different natural disaster metaphor.

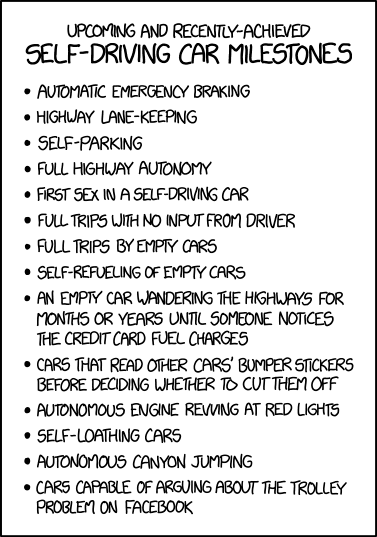

Note to AI researchers: why don't you forget about chess for a while

[Another game post brought to you by Kruzno.]

By digging into the rich history of board games (and possibly doing a little tweaking) I suspect we can come up with other abstract strategy games of perfect information that put humans and machines on a more equal footing, and more importantly, provide as or more interesting fields of study for AI. Of course, there's always go, but wouldn't it be fun to do something different for a change?

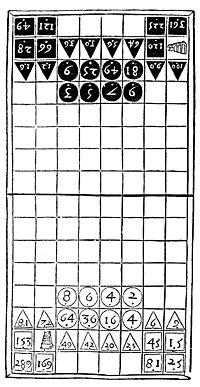

Whenever you need to make a survey of games, the best place to start is almost always David Parlett (followed by Sid Sackson but more on that later). Lots of promising potential candidates both historical and modern. To get things started, how about the medieval game that for a while rivaled chess for popularity, rithmomachy?

From Wikipedia.

Any other suggestions?

By digging into the rich history of board games (and possibly doing a little tweaking) I suspect we can come up with other abstract strategy games of perfect information that put humans and machines on a more equal footing, and more importantly, provide as or more interesting fields of study for AI. Of course, there's always go, but wouldn't it be fun to do something different for a change?

Whenever you need to make a survey of games, the best place to start is almost always David Parlett (followed by Sid Sackson but more on that later). Lots of promising potential candidates both historical and modern. To get things started, how about the medieval game that for a while rivaled chess for popularity, rithmomachy?

From Wikipedia.

Very little, if anything, is known about the origin of the game. But it is known that medieval writers attributed it to Pythagoras, although no trace of it has been discovered in Greek literature, and the earliest mention of it is from the time of Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054).

The name, which appears in a variety of forms, points to a Greek origin, the more so because Greek was little known at the time when the game first appeared in literature. Based upon the Greek theory of numbers, and having a Greek name, it is still speculated by some that the origin of the game is to be sought in the Greek civilization, and perhaps in the later schools of Byzantium or Alexandria.

The first written evidence of Rithmomachia dates back to around 1030, when a monk, named Asilo, created a game that illustrated the number theory of Boëthius' De institutione arithmetica, for the students of monastery schools. The rules of the game were improved shortly thereafter by the respected monk, Hermannus Contractus, from Reichenau, and in the school of Liège. In the following centuries, Rithmomachia spread quickly through schools and monasteries in the southern parts of Germany and France. It was used mainly as a teaching aid, but, gradually, intellectuals started to play it for pleasure. In the 13th century Rithmomachia came to England, where famous mathematician Thomas Bradwardine wrote a text about it. Even Roger Bacon recommended Rithmomachia to his students, while Sir Thomas More let the inhabitants of the fictitious Utopia play it for recreation.

The game was well enough known as to justify printed treatises in Latin, French, Italian, and German, in the sixteenth century, and to have public advertisements of the sale of the board and pieces under the shadow of the old Sorbonne.

Any other suggestions?

Thursday, December 14, 2017

Wednesday, December 13, 2017

If we are going to talk about games, everyone should probably read this first.

[Brought to you by Kruzno]

I've long been an advocate of board games (particularly the abstract strategy variety). They're wonderful for both recreation and education, they can provide intriguing examples of mathematical and logical concepts, and, of particular relevance these days, they can be a great testing ground for AI research.

All of these purposes would be better suited if people were familiar with a wider range of games and knew more about their history. This brings us to the game designer and historian, David Parlett and his indispensable Oxford history of board games. I'll be coming back to this book in the future, but for now, this is just a general recommendation. If you're an educator, a researcher, or just someone with an interest in the topic, you should definitely try to get your hands on a copy.

I've long been an advocate of board games (particularly the abstract strategy variety). They're wonderful for both recreation and education, they can provide intriguing examples of mathematical and logical concepts, and, of particular relevance these days, they can be a great testing ground for AI research.

All of these purposes would be better suited if people were familiar with a wider range of games and knew more about their history. This brings us to the game designer and historian, David Parlett and his indispensable Oxford history of board games. I'll be coming back to this book in the future, but for now, this is just a general recommendation. If you're an educator, a researcher, or just someone with an interest in the topic, you should definitely try to get your hands on a copy.

The powerful combination of effective marketing and a product that's literally addictive

[The New Yorker piece, "The Family That Built an Empire of Pain” by Patrick Radden Keefe is an extraordinary piece of longform journalism and you should take the time to read the whole thing, particularly if you have any interest in scientific research, healthcare, and the second coming of the gilded age. I'm not going to attempt any kind of comprehensive summary (like I said, just read it), but I am going to do a few blog post highlighting some points that jump out at me.]

If you've ever wondered what would happen if you crossed an unscrupulous ad man with an unscrupulous pharmaceutical executive.

If you've ever wondered what would happen if you crossed an unscrupulous ad man with an unscrupulous pharmaceutical executive.

Arthur [Sackler] helped pay his medical-school tuition by taking a copywriting job at William Douglas McAdams, a small ad agency that specialized in the medical field. He proved so adept at this work that he eventually bought the agency—and revolutionized the industry. Until then, pharmaceutical companies had not availed themselves of Madison Avenue pizzazz and trickery. As both a doctor and an adman, Arthur displayed a Don Draper-style intuition for the alchemy of marketing. He recognized that selling new drugs requires a seduction of not just the patient but the doctor who writes the prescription.

Sackler saw doctors as unimpeachable stewards of public health. “I would rather place myself and my family at the judgment and mercy of a fellow-physician than that of the state,” he liked to say. So in selling new drugs he devised campaigns that appealed directly to clinicians, placing splashy ads in medical journals and distributing literature to doctors’ offices. Seeing that physicians were most heavily influenced by their own peers, he enlisted prominent ones to endorse his products, and cited scientific studies (which were often underwritten by the pharmaceutical companies themselves). John Kallir, who worked under Sackler for ten years at McAdams, recalled, “Sackler’s ads had a very serious, clinical look—a physician talking to a physician. But it was advertising.” In 1997, Arthur was posthumously inducted into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame, and a citation praised his achievement in “bringing the full power of advertising and promotion to pharmaceutical marketing.” Allen Frances put it differently: “Most of the questionable practices that propelled the pharmaceutical industry into the scourge it is today can be attributed to Arthur Sackler.”

Advertising has always entailed some degree of persuasive license, and Arthur’s techniques were sometimes blatantly deceptive. In the nineteen-fifties, he produced an ad for a new Pfizer antibiotic, Sigmamycin: an array of doctors’ business cards, alongside the words “More and more physicians find Sigmamycin the antibiotic therapy of choice.” It was the medical equivalent of putting Mickey Mantle on a box of Wheaties. In 1959, an investigative reporter for The Saturday Review tried to contact some of the doctors whose names were on the cards. They did not exist.

During the sixties, Arthur got rich marketing the tranquillizers Librium and Valium. One Librium ad depicted a young woman carrying an armload of books, and suggested that even the quotidian anxiety a college freshman feels upon leaving home might be best handled with tranquillizers. Such students “may be afflicted by a sense of lost identity,” the copy read, adding that university life presented “a whole new world . . . of anxiety.” The ad ran in a medical journal. Sackler promoted Valium for such a wide range of uses that, in 1965, a physician writing in the journal Psychosomatics asked, “When do we not use this drug?” One campaign encouraged doctors to prescribe Valium to people with no psychiatric symptoms whatsoever: “For this kind of patient—with no demonstrable pathology—consider the usefulness of Valium.” Roche, the maker of Valium, had conducted no studies of its addictive potential. Win Gerson, who worked with Sackler at the agency, told the journalist Sam Quinones years later that the Valium campaign was a great success, in part because the drug was so effective. “It kind of made junkies of people, but that drug worked,” Gerson said. By 1973, American doctors were writing more than a hundred million tranquillizer prescriptions a year, and countless patients became hooked. The Senate held hearings on what Edward Kennedy called “a nightmare of dependence and addiction.”

Tuesday, December 12, 2017

The dark magic of the market – – OxyContin edition

[The New Yorker piece, "The Family That Built an Empire of Pain” by Patrick Radden Keefe is an extraordinary piece of longform journalism and you should take the time to read the whole thing, particularly if you have any interest in scientific research, healthcare, and the second coming of the gilded age. I'm not going to attempt any kind of comprehensive summary (like I said, just read it), but I am going to do a few blog post highlighting some points that jump out at me.]

One of the most pernicious ideas of the past few decades is that markets are both magical and moral, that simply removing government oversight and unleashing market forces would always, automatically improve everything. This is, at best, a questionable approach, but it becomes absolutely disastrous when selectively applied. Removing certain regulations while keeping in place anticompetitive rules and government granted monopolies such as patents and copyrights produces a worst of both worlds scenario (at least for the consumer).

While the roots of this philosophy are complex and long-standing, its success can be explained in large part, perhaps even almost entirely, by the way it was subsidized by interested parties. Industries that stand to make windfall profits and billionaires with an ideological ax to grind (huge overlap in these two) pour stunning amounts of money into biased and often worthless academic research, fake institutes and think tanks that start with their conclusions and work backwards, and propaganda/lobbying operations that build themselves as educational foundations. You would have to put scare quotes around every other word to do this justice.

In this particular instance, the single-minded pursuit of optimal profit, rather than serving the social good, corrupted the process and inflicted a huge toll.[emphasis added.]

A 1995 memo sent to the launch team emphasized that the company did “not want to niche” OxyContin just for cancer pain. A primary objective in Purdue’s 2002 budget plan was to “broaden” the use of OxyContin for pain management. As May put it, “What Purdue did really well was target physicians, like general practitioners, who were not pain specialists.” In its internal literature, Purdue similarly spoke of reaching patients who were “opioid naïve.” Because OxyContin was so powerful and potentially addictive, David Kessler told me, from a public-health standpoint “the goal should have been to sell the least dose of the drug to the smallest number of patients.” But this approach was at odds with the competitive imperatives of a pharmaceutical company, he continued. So Purdue set out to do exactly the opposite.

Sales reps, May told me, received training in “overcoming objections” from clinicians. If a doctor inquired about addiction, May had a talking point ready. “ ‘The delivery system is believed to reduce the abuse liability of the drug,’ ” he recited to me, with a rueful laugh. “Those were the specific words. I can still remember, all these years later.” He went on, “I found out pretty fast that it wasn’t true.” In 2002, a sales manager from the company, William Gergely, told a state investigator in Florida that Purdue executives “told us to say things like it is ‘virtually’ non-addicting.”

May didn’t ask doctors simply to take his word on OxyContin; he presented them with studies and literature provided by other physicians. Purdue had a speakers’ bureau, and it paid several thousand clinicians to attend medical conferences and deliver presentations about the merits of the drug. Doctors were offered all-expenses-paid trips to pain-management seminars in places like Boca Raton. Such spending was worth the investment: internal Purdue records indicate that doctors who attended these seminars in 1996 wrote OxyContin prescriptions more than twice as often as those who didn’t. The company advertised in medical journals, sponsored Web sites about chronic pain, and distributed a dizzying variety of OxyContin swag: fishing hats, plush toys, luggage tags. Purdue also produced promotional videos featuring satisfied patients—like a construction worker who talked about how OxyContin had eased his chronic back pain, allowing him to return to work. The videos, which also included testimonials from pain specialists, were sent to tens of thousands of doctors. The marketing of OxyContin relied on an empirical circularity: the company convinced doctors of the drug’s safety with literature that had been produced by doctors who were paid, or funded, by the company.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)