Mike the Mad Biologist points us to this one.

From Karl Alexander (John Dewey Professor of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University):

UPDATE:

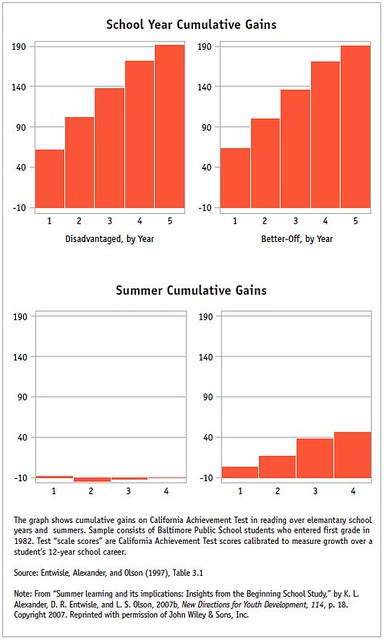

This seems like a good time to remind everyone about some of the other previously mentioned challenges these kids face:We discovered that about two-thirds of the ninth-grade academic achievement gap between disadvantaged youngsters and their more advantaged peers can be explained by what happens over the summer during the elementary school years.Mike goes on to point out the obvious question this raises about the fire-the-teachers approach to education reform.

I also want to point out that the higher performing group isn’t necessarily high income, but simply better off. In the context of the Baltimore City school system, that usually means solidly middle class, with parents who are likely to have gone to college versus dropping out.

Statistically, lower income children begin school with lower achievement scores, but during the school year, they progress at about the same rate as their peers. Over the summer, it’s a dramatically different story. During the summer months, disadvantaged children tread water at best or even fall behind. It’s what we call “summer slide” or “summer setback.” But better off children build their skills steadily over the summer months. The pattern was definite and dramatic. It was quite a revelation.

Hart and Risley also found that, in the first four years after birth, the average child from a professional family receives 560,000 more instances of encouraging feedback than discouraging feedback; a working- class child receives merely 100,000 more encouragements than discouragements; a welfare child receives 125,000 more discouragements than encouragements.