[Note: David Weakliem recently looked at the actual data on this going back to the eighties. Check out his analysis here.]

As alluded to recently, Joseph and I have been having an argument about political strategy. I contended that the Democrats should be focusing on three issues where the GOP had staked out especially unpopular positions: reproductive rights, the insurrection; and Social Security and Medicare. Joseph countered that, largely because of Trump's public commitment not to cut these programs. The GOP was, in a sense inoculated against these attacks.

For the record, my co-blogger Joseph is possibly the smartest person I know. What's more, he cited a number of other very smart people who were in general agreement including Josh Marshall who is probably our sharpest political analyst. I get very nervous when I find myself disagreeing with either, let alone both. And the Democratic establishment was clearly on board (more on that later in the post).

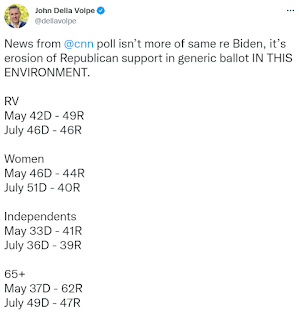

I wasn't exactly persuaded but I had enough doubts about my position that I decided back-burner the topic and focus on other things. Then I saw this:

If data and common sense point to Republican vulnerability on the issue, why is conventional wisdom converging in the opposite direction? Perhaps it's because the pundits who shaped that conventional wisdom have always been overly invested in the idea that Trump's position on Social Security and Medicare was a key part of his success.

Think back to 2015.

Pundits were at a loss to explain the rise of Donald Trump which is part of the reason so many tried to deny it was even happening. (Remember Nate Cohen's series of NYT articles in 2015 arguing that there was no way DJT could beat various candidates despite the fact he was crushing them in the polls.) For people whose job it is to explain things, this is incredibly disconcerting, so when Trump broke with the Republican line on two incredibly unpopular GOP positions, taxing the rich and cutting Social Security and Medicare, the pundit class finally had a theory they could converge on: Trump's success came from his combination of reactionary and liberal populist positions.

This was always a thin thread to hang an interpretation on. The stand was hardly the second coming of Huey P. Long. These GOP positions were so unpopular that even a majority of Republican voters opposed them. At most, Trump had mixed a couple of moderate positions into his reactionary and autocratic platform.

What's more, they were always a relatively small part of the mix. If you read over the real-time coverage of the campaign, you'll see that SS and Medicare weren't that prominent and the guarantees left considerable wiggle room. [Emphasis added.]

Below is a head-to-head rundown on where Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton stand — as best as anyone can tell. Incidentally, Trump's website makes little mention of Social Security; most of his policy positions come from what he has said in debates or speeches. Clinton's site has more details about her proposals and she has fleshed them out elsewhere.

...

At a June rally in Phoenix, Trump said: “We’re going to save your Social Security without killing it like so many people want to do.” During the campaign, Trump said something similar: “I will do everything within my power not to touch Social Security, to leave it the way it is.”

...

But Trump left the window open to future reforms in his comments to AARP, saying: “As our demography changes, a prudent administration would begin to examine what changes might be necessary for future generations.”

So his position wasn't that far out of line with lots of Republicans, basically saying we may cut later rather than we should cut now. More importantly, this was never one of the main points of his campaign. I may have missed something in my Google searches, but it appears that Trump didn't talk that much about the issue (it merits two brief mentions in his 6,000+ word announcement speech, neither in the first half) and that it didn't get that much coverage. Perhaps there is data out there that shows that these positions were a major driver of support or that protecting Social Security and Medicare was top-of-mind when people thought Donald Trump, but if so it would be despite sparse coverage and a lack of emphasis from Trump himself.

In the pundit class, however, the relationship loomed large.

From Ezra Klein's influential Vox piece.

Trump is the only Republican running who actually agrees with the GOP base on this one. "They're gonna cut Social Security. They're gonna cut Medicare. They're gonna cut Medicaid," he said on Fox & Friends. "I'm the one saying that's saying I'm not gonna do that!"

And that's what makes a candidate like Trump potentially dangerous. On immigration, Trump holds a hard-line position that the Republican Party establishment has tried to mute, and so far Republican voters are loving it. On Social Security and Medicare, Trump — who opposes cuts — is closer to Republican voters than the party establishment is. On free trade deals, Trump shares a skepticism held by about half of Republican voters, but that's usually suppressed by the party's powerful business wing.

Most candidates who tried to stack this many heterodoxies would be quickly squelched by the party establishment. But Trump isn't beholden to the GOP for money, staff, power, or press attention. That frees him to take positions that Republican voters like but Republican Party elites loathe.

It may be true that support for Trump, so far, is about personality rather than policy. But as the primary wears on, Republican voters might find that they actually agree with him. And that's going to put the rest of the Republican field — all those candidates who were playing by the establishment's rules — in a very tough position.

Klein does get points for pulling away from the then popular "Trump doesn't have a chance" camp, but as mentioned before, there doesn't seem to much evidence that Social Security and Medicare played a big role in Trump's securing the nomination.

Though it has fallen down the memory hole, Trump's real break with the Republican Party line was not over entitlements, but over taxes.

Donald Trump is finally showing us more of his economic plan beyond the "Make America Great Again" slogan on his red hat.

America has now learned:

-- He wants to tax the rich more and the middle class less.

-- He wants to lower corporate taxes.

-- He wants to cut government spending and stop raising the debt ceiling.

"The hedge fund people make a lot of money and they pay very little tax," Trump said in an interview Wednesday with Bloomberg. "I want to lower taxes for the middle class."

In short, Trump is willing to raise taxes on himself and those like him.

We all know how that worked out.

Fast forward to 2022. Republicans are talking about cutting, privatizing, or killing Social Security with an openness they hadn't shown in at least twenty years. Trump himself lost interest in the topic long ago. But among the pundit class and much of the Democratic establishment, a few six-year old statements had permanently inoculated not just Trump, but the entire GOP on this issue.

What's remarkable here is not just the convergence but the certainty. A large part of the Republican Party is pissing on the third rail of American politics and yet no influential Democrats thought it was worth pulling the switch just in case the power was on.

If attacks on Social Security have eroded seniors' support for the GOP, they have done so almost entirely on their own. Progressives seldom mention the issue. AARP has been uncharacteristically quiet on the matter. Talking Points Memo, probably the best progressive political news and analysis site has dropped it entirely as far as I can tell.

“Privatize social security” @bgmasters tells FreedomWorks, saying he will bring fresh thinking to the US Senate. Hard to tell if that sunk in this room, where many are of social security age. #AZprimary pic.twitter.com/jNqKbCiMSa

— Kyung Lah (@KyungLahCNN) June 24, 2022

Even in Florida, which has a lot of seniors, Val Demings is all but silent on the topic, despite the fact that her opponent and his fellow senator are both on the record as wanting to cut or kill the program.

There's no conspiracy here, no hidden agenda. These people simply believe with a great deal of confidence that while pushing back against Republican attacks on Medicare and particularly Social Security might be the right thing to do, it is not a winning political strategy.

If there were any doubt in the Democratic establishment's mind, hedging the bet would be cheap, easy and pretty much risk free. A few campaign ads, some viral videos, a couple of lines in stump speeches, a bullet point in campaign websites, raising the subject in interviews.

The most bizarre part of this is that for decades, one of the unassailable truths of American politics was that attacking Social Security and Medicare was bad for Republicans and defending them was good for Democrats, and yet, in the space of a few years for no particularly good reason, the political establishment became absolutely certain of the exact opposite.