I've been thinking a lot recently about the Henry James novella The Beast in the Jungle. If you've never read it (or have read but forgotten it), here's the synopsis:

John Marcher, the protagonist, is reacquainted with May Bartram, a woman he knew ten years earlier while living in southern Italy, who remembers his odd secret: Marcher is seized with the belief that his life is to be defined by some catastrophic or spectacular event, lying in wait for him like a "beast in the jungle". May decides to buy a house in London with the money she inherited from a great aunt, and to spend her days with Marcher, curiously awaiting what fate has in store for him. Marcher is a hopeless fatalist, who believes that he is precluded from marrying so that he does not subject his wife to his "spectacular fate".

He takes May to the theater and invites her to an occasional dinner, but does not allow her to get close to him. As he sits idly by and allows the best years of his life to pass, he takes May down as well, until the denouement where he learns that the great misfortune of his life was to throw it away, and to ignore the love of a good woman, based upon his preposterous sense of foreboding.

What if it wasn't just one man but an entire culture that built its identity around an overwhelming but unfounded belief that it was destined to see its world upended by some great, unknown Next Big Thing?

Obviously the definitions we're using here are largely subjective and open to debate, but I’d argue that we haven't had an honest-to-god Next Big Thing since the 90s. There have certainly been technological advances that have changed our daily life, but very little that registers on the scale that we saw from, for example, 1876 to 1896, a period that included the telephone, the invention of recorded sound, Pasteur's vaccines, the light bulb, practical electric motors, modern electrical engineering, motion pictures, internal combustion, automobiles, the first successful engine-driven heavier-than-air (unmanned) flight, x-rays, the linotype and the birth of modern printing, wireless telecommunication, and probably a good dozen that I'm leaving out. (don't get me started on aluminum or Luther Burbank.) I could make a similar, albeit slightly less impressive list starting in 1945 and going through 1970.

Those were, of course, exceptional periods in human history but if we want to play with the big boys, that is the standard we need to meet.

Going back 25 years from today, the only thing that jumps out as a life-changing, paradigm-shifting Next Big Thing is the smartphone and just barely possibly social media. There is no question that the small 2001 monolith/Mother Box most of us carry in our pockets has had a tremendous impact on the way we live, but it is not all that recent and, more importantly, it is largely the result of combining the next big things of the 80's and 90's, the internet, cell phones, civilian GPS, digital photography. Likewise, social media feels like a small extension of existing tech that had big ramifications.

Even if we allow the smartphone and social media, the introduction of the iPhone was 15 years ago and Facebook is older than that, meaning that you have to over thirty to have adult memories of what it's like for a piece of technology to radically change everyone's lives.

This doesn't necessarily suggest any kind of stagnation. The end of the 19th century and the post-war era should probably be treated as anomalies. What we are living through now is arguably fairly normal with steady incremental advances in most fields (cancer treatments, batteries, rockets, etc.) and a few big breakthroughs around a handful of specific problems (mRNA vaccines).

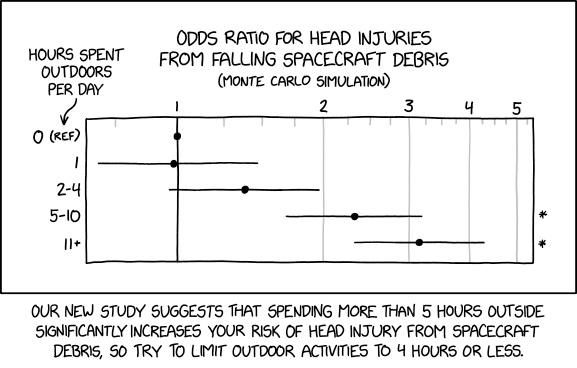

Unfortunately, we have collectively conditioned ourselves to believe that's not enough, that we are or at least should be living in a period of radical and ubiquitous technological change proceeding along an already steep exponential curve. Like James's protagonist, we have convinced ourselves that we are destined to experience some kind of great and potentially terrible event, specifically in our case the kind of thing we read about in old science fiction stories. The result has been to make us all a little bit crazy and in some cases, gullible as hell.