I realized that now when I hear the word "unicorn," I think of a tech bro pitching a 21st Century Ponzi scheme to some clueless venture capitalists. Here's something to wash the taste of all of those WeWorks and Pelotons out of your mind.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, December 20, 2019

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Revisiting the catharsis thread

Recent events have got me thinking about this point from four years ago.

I haven't followed the press coverage that closely, but based on what I've come across from NPR and the few political sites I frequent, I get the feeling that the center-left media is more likely to discuss the doctoring of the tapes than to focus on the gory specifics of harvesting fetal tissue. I'd need to check sources like CNN before making a definitive statement, but it appears that the videos are having exceptionally little effect on what should have been their target audience.

Instead, their main impact seems to have been on the far right. The result has been to widen what was already a dangerous rift. The pragmatic wing looks at defunding as a futile gesture with almost no chance of success and large potential costs. The true believers are approaching this on an entirely different level. It has become an article of faith for them that, as we speak, babies are being killed, dismembered and sold for parts. They demand action, even if it's costly and merely symbolic, as long as it's cathartic.

I've been arguing for quite a while now that we need to pay more attention to the catharsis in politics (such as with the reaction to the first Obama/Romney debate), particularly with the Tea Party. Conservative media has long been focused on feeding the anger and the outrage of the base while promising victory just around the corner. This has produced considerable partisan payoff but at the cost of considerable anxiety and considerable disappointment, both of which produce stress and a need for emotional release.

There's a tendency to think of trading political capital for catharsis as being irrational, but it's not. There is nothing irrational about doing something that makes you feel better. That's the real problem for the GOP leaders: shutting down the government would be cathartic for many members of the base. It would be difficult to get the base to defer their catharsis, even if the base trusted the leaders to make good on their promise that things will get better.

For now, the Tea Party is inclined to do what feels good, whether it's supporting an unelectable candidate or making a grandstanding play. It's not entirely clear what Boehner and McConnell can do about that.

I've been arguing for quite a while now that we need to pay more attention to the catharsis in politics (such as with the reaction to the first Obama/Romney debate), particularly with the Tea Party. Conservative media has long been focused on feeding the anger and the outrage of the base while promising victory just around the corner. This has produced considerable partisan payoff but at the cost of considerable anxiety and considerable disappointment, both of which produce stress and a need for emotional release.The difference now is that the head of the party is one of the base.

There's a tendency to think of trading political capital for catharsis as being irrational, but it's not. There is nothing irrational about doing something that makes you feel better. That's the real problem for the GOP leaders: shutting down the government would be cathartic for many members of the base. It would be difficult to get the base to defer their catharsis, even if the base trusted the leaders to make good on their promise that things will get better.

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

Planned Parenthood, channeled information and catharsis

This recent TPM post about the looming government shut-down ties in with a couple of ideas we've discussed before. [Emphasis added]Here's what we had to say about the GOP reaction to those videos a month ago.

Facing a Sept. 30 deadline to fund the government, GOP leaders in both chambers decided they would fast-track standalone anti-abortion bills in an effort to allow conservative Republicans to express their anger over a series of “sting” videos claiming to show that Planned Parenthood is illegally harvesting the tissue of aborted fetuses. The leadership hoped that with those votes out of the way, the path would be clear for long-delayed bills to fund the government in the new fiscal year, even if those bills contained money for Planned Parenthood.

But anti-abortion groups and conservative House members are not backing down from their hard line. They are reiterating that they will not vote for bills that include Planned Parenthood funding under any circumstances, despite the maneuvering by leaders to vent their outrage over the videos. If anything, anti-abortion groups are amping up the pressure on lawmakers not to back down from the fight.

[I really should have said "causing supporters to push," but it's too late to worry about that now.]

Fetal tissue research will make most people uncomfortable, even those who support it. If you were a Republican marketer, the ideal target for these Planned Parenthood stories would be opponents and persuadables. By contrast, you would want the videos to get as little play as possible among your supporters. With that group, you have already maxed out the potential gains – – both their votes and their money are reliably committed – – and you run a serious risk of pushing them to the level where they start demanding more extreme action.

With all of the normal caveats -- I have no special expertise. I only know what I read in the papers. There's a fundamental silliness comparing a political movement to a business -- it seems to me that in marketing terms, the PP tapes have been badly mistargeted. They have had the biggest viewership and impact in the segment of the voting market where they would do the least good and the most damage (such as pushing for a government shutdown on the eve of a presidential election).

I haven't followed the press coverage that closely, but based on what I've come across from NPR and the few political sites I frequent, I get the feeling that the center-left media is more likely to discuss the doctoring of the tapes than to focus on the gory specifics of harvesting fetal tissue. I'd need to check sources like CNN before making a definitive statement, but it appears that the videos are having exceptionally little effect on what should have been their target audience.

Instead, their main impact seems to have been on the far right. The result has been to widen what was already a dangerous rift. The pragmatic wing looks at defunding as a futile gesture with almost no chance of success and large potential costs. The true believers are approaching this on an entirely different level. It has become an article of faith for them that, as we speak, babies are being killed, dismembered and sold for parts. They demand action, even if it's costly and merely symbolic, as long as it's cathartic.

I've been arguing for quite a while now that we need to pay more attention to the catharsis in politics (such as with the reaction to the first Obama/Romney debate), particularly with the Tea Party. Conservative media has long been focused on feeding the anger and the outrage of the base while promising victory just around the corner. This has produced considerable partisan payoff but at the cost of considerable anxiety and considerable disappointment, both of which produce stress and a need for emotional release.

There's a tendency to think of trading political capital for catharsis as being irrational, but it's not. There is nothing irrational about doing something that makes you feel better. That's the real problem for the GOP leaders: shutting down the government would be cathartic for many members of the base. It would be difficult to get the base to defer their catharsis, even if the base trusted the leaders to make good on their promise that things will get better.

For now, the Tea Party is inclined to do what feels good, whether it's supporting an unelectable candidate or making a grandstanding play. It's not entirely clear what Boehner and McConnell can do about that.

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

If you've gone through the holidays without hearing "Sugar Rum Cherry"...

... you have not had a cool Christmas.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

Starting with some news you can use.

You've got to be kidding me. After all these years... pic.twitter.com/dhNgjCVzeG— Chuck B (@chUckbUte) December 15, 2019

Elizabeth Warren has lost some political ground since the summer, but her wealth tax proposal is doing just fine

Fox News poll shows 68% of Americans support it - including 83% of Democrats, 68% of Independents, and 51% of Republicanshttps://t.co/pWKOGMvaDn— John Harwood (@JohnJHarwood) December 16, 2019

It is frankly bizarre. He cld defintely hustle a mid-40s electoral college win, as he did in 2016. But objectively he is in a daunting, daunting position. Stuck w 10 pt approval deficit, more than 50% say they refused to vote for him. Top opponents winning by 5 to 10 pts. C'mon.— Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) December 16, 2019

This should be a bigger story.

Wisconsin is set to purge 234,000 voters, 7% of electorate

Tonight Georgia is cancelling 300,000 registrations, 4% of electorate https://t.co/wOMypmPU12— Ari Berman (@AriBerman) December 16, 2019

Every article about drones should mention they are and will ever be extremely loud and almost certainly viewed as a serious neighborhood nuisance. https://t.co/QfwnrgwkEg— David King (@dk2475) December 12, 2019

6\ Here @elonmusk forgets about the existence of Ohm's Law. Imagine the resistance on wires going from Arizona to NYC!https://t.co/2GCn6WnqMM— "Elon Says" (@ElonBachman) December 13, 2019

Baker is terrible at his job.

@peterbakernyt on MSNBC on Thursday said with a perfectly straight face that “both sides” of the House Judiciary Cmte were keeping the fact checkers busy. It’s not just the cult like behavior of the GOP. It’s the NYT insistence that the GOP is not actually a cult that dooms us.— Kevin Judge (@kevster57) December 14, 2019

—

Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) December

15, 2019

2016 showed us that the press still has a horrible problem with misogyny and that it's especially bad at the NYT.

When Buttigieg was on the Daily he was not asked why people see him as inauthentic or opportunistic.

But Warren gets asked repeatedly why she's "alienating" or "uncompromising"

"Why do people hate you?" is a question asked only to women https://t.co/UcWxm0Q6kR— Charlotte Alter (@CharlotteAlter) December 16, 2019

Maybe someone will noticehttps://t.co/8MpC7n7uQN— Erik Halvorsen (@erikhalvorsen18) December 15, 2019

We've got your good billionaire press lords and we've got...

In fairness LPJ was running dangerously low on money and surely couldn’t afford to keep a 16 person publication running. She’s down to her last $24 billion. https://t.co/STsArXIHMm— dylan matthews (@dylanmatt) December 14, 2019

We'll be coming be coming back to this one.

—

Rachel Cohen (@rmc031) December

14, 2019

I also wonder if the bankruptcies have something to do with which farmers (and companies) are getting the money.

As a result, farmers have suffered, with a number going bankrupt, despite a bailout *twice the size of Obama's auto bailout* 5/ https://t.co/hZlIEojcvz— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) December 15, 2019

Sincere question for those out there with relevant expertise, to what extent does the existence of today's unicorns depend on the innovations of the infamous Match King?

The Match King did make and sell matches. https://t.co/42wzLieUlF— Russ Mitchell (@russ1mitchell) December 14, 2019

And finally, some yak karma.

—

Charles P. Pierce (@CharlesPPierce) December

15, 2019

Monday, December 16, 2019

More on data science

This is Joseph

This is an excellent article on machine learning. In particular I liked this:

The article also highlights the limitations of the data generating process. Is not having contact with the health system mean one is healthy? In the CPRD it seems like the people without blood pressures (routinely collected during visits to a physician) were both the most healthy and the least. Lack of contact with the medical system is complicated but these participants often form the reference group.

Anyway, go, read, and enjoy.

This is an excellent article on machine learning. In particular I liked this:

As an extreme illustration, an algorithm designed to predict a rare condition found in only 1% of the population can be extremely accurate by labeling all individuals as not having the condition. This tool is 99% accurate, but completely useless. Yet, it may “outperform” other algorithms if accuracy is considered in isolation.It is even better discussed by Frances Wooley and Thomas Lumley using the example of classification of sexual orientation by facebook. This isn't to say that machine learning isn't useful but the proper penalty functions or sampling characteristics need to be developed (Thomas has a great discussion of this). A simple measure of accuracy is going to fail in all sorts of cases where simple but useless rules do extremely well (most people do not have pancreatic cancer and I can be exceedingly accurate guessing that any one person does not have it). It isn't that the problem is intractable, but that it isn't simply a case of running a technique on whatever data happens to be lying around. Like most worthwhile data science problems, doing the work well is what is hard.

The article also highlights the limitations of the data generating process. Is not having contact with the health system mean one is healthy? In the CPRD it seems like the people without blood pressures (routinely collected during visits to a physician) were both the most healthy and the least. Lack of contact with the medical system is complicated but these participants often form the reference group.

Anyway, go, read, and enjoy.

Friday, December 13, 2019

Choice of metric: the perils of data science

This is Joseph

I was reading this article and I decided it was a good example of how the choice of metrics can really change the answer to a study question. The author concludes that the best general of history was Napoleon:

I was reading this article and I decided it was a good example of how the choice of metrics can really change the answer to a study question. The author concludes that the best general of history was Napoleon:

Among all generals, Napoleon had the highest WAR (16.679) by a large margin. In fact, the next highest performer, Julius Caesar (7.445 WAR), had less than half the WAR accumulated by Napoleon across his battles. Napoleon benefited from the large number of battles in which he led forces. Among his 43 listed battles, he won 38 and lost only 5.So what was the choice of metric:

Inspired by baseball sabermetrics, I opted to use a system of Wins Above Replacement (WAR). WAR is often used as an estimate of a baseball player’s contributions to his team. It calculates the total wins added (or subtracted) by the player compared to a replacement-level player. For example, a baseball player with 5 WAR contributed 5 additional wins to his team, compared to the average contributions of a high-level minor league player. WAR is far from perfect, but provides a way to compare players based on one statistic.The problem with this metric is that it presumes that all players have an equal opportunity to accumulate wins. This leads to some odd outcomes:

Napoleon’s large battle count allowed him more opportunities to demonstrate his tactical prowess. Alexander the Great, despite winning all 9 of his battles, accumulated fewer WAR largely because of his shorter and less prolific career.Now it is true that the historical consensus is that both are good generals. But an unbroken string of impressive victories, against the regional superpower, gives a WAR of 4.370, a quarter of Napoleon's score. I am not sure that the historical consensus is that Alexander was mediocre besides Napoleon because of the number of battles. If anything, there is a perspective that having to fight more battles was actually a sign of a weaker general. Consider these quotes:

There is no instance of a nation benefitting from prolonged warfare.

For to win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.

Hence to fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting.

The best victory is when the opponent surrenders of its own accord before there are any actual hostilities... It is best to win without fighting.All of this isn't to say that I am not in awe of the work done on this project. It was amazing. But it is a good time to reflect on the issues with any one-dimensional metric when trying to evaluate something as complicated as warfare.

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Thursday Tweets (Having an exceptionally busy schedule had nothing to do with this scheduling decision.)

Marketplace is the best news show on public radio,

Mike Judge is, once again, on top of it.

One more hit on Peloton

Wall Street is an idiot, part 3, 495. https://t.co/f3GgXGuFWa— Kai Ryssdal (@kairyssdal) December 3, 2019

Mike Judge is, once again, on top of it.

"Contradicting the conventional wisdom, clearly defined ideological “lanes” don’t seem to exist in the minds of most voters," our Editor-In-Chief @johnmsides and @vavreck write in @washingtonpost. https://t.co/CagGyvyIxt— Monkey Cage (@monkeycageblog) December 3, 2019

One more hit on Peloton

Best hostage video I’ve seen in a while https://t.co/n52H0Fpcbl— Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) December 2, 2019

Remember when the secret ballot talk was basically just a joke? People seem to be taking it a little more seriously (though it's still a looong shot)There’s a Surprisingly Plausible Path to Removing Trump From Office - POLITICO Magazine https://t.co/30R2C5M4rN— Joe Nocera (@opinion_joe) December 2, 2019

More to the point, like the price estimates, they seem to be trending upward. Some enterprising reporter ought to dig through the various articles and press releases and see how fast these promises are moving.@RyanDeto— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 2, 2019

Don’t trust polls that match Democratic candidates against Trump. @rp_griffin explains why.#2020Election https://t.co/tNbMerRKxZ— Monkey Cage (@monkeycageblog) December 1, 2019

Finally entering the public domain next year. Good thing copyright duration is so reasonable these days! https://t.co/YHXaIWBC9P— Annemarie Bridy (@AnnemarieBridy) December 12, 2019

Utah is planning to require some low-income residents to apply for work with at least 48 employers in order gain Medicaid coverage. https://t.co/2BlUHyQkcZ— Sarah Kliff (@sarahkliff) December 11, 2019

If Bitcoin Looks Like It Isn’t Trading, It’s Because It Isn’t.

About 9.1 million bitcoins, representing about 51% of those outstanding, haven’t changed hands in at least six monthshttps://t.co/DvXYiN9Nos— Nouriel Roubini (@Nouriel) December 10, 2019

Respectable showing, but you'd need to work in 3-d printing and virtual reality if you really want to impress the judges.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 10, 2019

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Normalizing the Ponzi Threshold

The blurb doesn't actually show up in the linked article, but it pretty much captures the gist.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Away sold $150 million worth of luggage in 2018. But if the company is to keep growing, it needs to sell more than just suitcases and weekenders, which are relatively infrequent purchases. Founders Jen Rubio and Steph Korey say their plan is to enter new categories of products that are related to travel, and they’re teasing us with hints of what they might be.

Obviously, the magnitude of the Uber bubble dwarfs any valuation that Away has or is likely to reach, but as absurd as Uber’s story was, at least it was a tale about big, new things. Smart phone based ride sharing was a genuinely disruptive industry and while it was unlikely that any one company would achieve the dominance (or the profit margins) that Uber promised, the industry’s potential was substantial enough to get caught up in. It took a while for the realization that the original model could never support the money that had been poured into it.

With Away, everyone seemed to realize almost immediately that the company on its current path could not be worth 1.4 billion dollars, and yet no one seems particularly bothered by the fact. Instead we get a nonchalant “don’t worry, they’ll think of something.” Given the amounts of money we’re talking about here, that’s an absolutely insane reaction, but in the age of the unicorn, it’s not at all an uncommon one.

On a related note, Away is a horrible business run by creepy people. For more on that, I send you to the good folk at LGM.

Tuesday, June 13, 2017

Ponzi Thresholds

Another post based on Reeves Wiedeman's Uber article in New York magazine. This one sets up a concept I've been meaning to discuss with the tentative name of a Ponzi threshold. The basic idea is that sometimes overhyped companies that start out with viable business plans see their valuation become so inflated that, in order to meet and sustain investor expectations, they have to come up with new and increasingly fantastic longshot schemes, anything that sounds like it might possibly pay off with lottery ticket odds.Like I said, this is been bouncing around for quite a while. I may have even slipped in a previous reference that I've forgotten about. There are plenty of potential examples, but the following is the first time I've seen the phenomenon spelled out in such naked terms [emphasis added]:

Meanwhile, in an effort to show potential investors in an IPO that it has multiple revenue streams, Uber has expanded into a variety of industries tangentially related to its core business. In 2015, the company launched Uber Everything, an initiative to figure out how it could move things in addition to people, and when I visited Uber headquarters, the guest Wi-Fi password was a reference to Uber Freight, the company’s attempt to get into trucking. (A former employee said the password often seemed to be a subliminal message encouraging employees to focus on the company’s newest initiatives.) But moving things had its own complications. One former Uber Everything manager said the company had looked at transporting flowers or prescription drugs or laundry but found that the demographic of people who, for example, couldn’t afford a washer and dryer but would pay to have their laundry delivered was a small one. Uber Rush, a delivery service in New York, had become “a nice little business,” the manager said, “but at Uber, you’re looking for a billion-dollar business, not a nice little business.”

It turned out that food delivery was the only area that made much sense, though even that was difficult. In the past year, food-delivery companies SpoonRocket, TinyOwl, Take Eat Easy, and Maple have all ceased operations. Postmates said in 2015 that it could be profitable in 2016, at which point it pushed the date to 2017. Its target is now 2018. “It absolutely does not work as a one-to-one business — picking up a burrito from Chipotle and delivering it,” a former Uber Eats manager said. “It has to be ‘I’m picking up ten orders from Chipotle, and I’m picking up this person next to Chipotle, and I’m gonna drop the burritos off along the way.’ ” Uber Eats has grown significantly, but getting the business up and running had required considerable subsidies, and the manager said it was rumored that a significant portion of the company’s domestic losses were coming from Uber Everything.

Uber’s expansion into an ever-widening gyre of business interests makes sense for a company looking to justify a huge valuation, but it has drawn criticism from some who wonder why the company is moving into so many different markets without becoming profitable in its first one. “It’s a Ponzi scheme of ambition,” Anand Sanwal, a venture-capital analyst, told me. “ ‘We’re gonna raise money on the promise of dominating an industry to come in order to pay for this thing that doesn’t make us money right now.’ ” He had recently conducted an unscientific poll of subscribers to his newsletter asking how many would invest in Uber today, even at a discounted valuation, and 77 percent said they wouldn’t. But the new initiatives have the benefit of keeping everyone excited about the future: In April, Uber held a conference in Dallas to explain why it planned to one day get into flying cars.

That phrase "looking to justify a huge valuation" is one that you need to contemplate for a few moments, let the logical implications wash over you. As I suggested before, like most New York magazine tech writers, Wiedeman does a good job capturing the telling detail, but is reluctant to draw that final Dr.-Tarr-and-Prof.-Feather conclusion, particularly when it threatens a cherished narrative.

There are at least two layers of crazy here. First, hype and next-big-thingism push Uber's value far beyond any defensible level, then, as reality sets in and investors realize that the original business model, though sound, can never possibly justify the money that's been put into the company, Uber's management responds with a series of more and more improbable proposals in order to keep the buzz going.

The phenomenon is not unique to this company but I can't think of another case this big or this blatant. (And they actually used the term "Ponzi scheme.")

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Tuesday Tweets -- If Andrew Gelman were on Twitter, I'd @ him on the first one

Make the time to read this mind-boggling @bykenarmstrong story about a "forensic" tool that law enforcement--including the FBI & CIA--use even though it's absurd on its face, is not supported by one iota of science, and can lead to wrongful convictions. https://t.co/UxyjNaAOmn— Pamela Colloff (@pamelacolloff) December 8, 2019

Good thread.

On McKinsey

I joined the San Francisco office of @McKinsey in 1987. Like members of the CIA and the Royal Household, we called it The Firm.

The Firm values deep professionalism as much as analytic and strategic chops. Values, not formal structures, hold it together.

1/18— Marty Manley 🌎 (@MartyManley) December 4, 2019

51 weeks ago pic.twitter.com/BXhRgj3qAA— Derek Thompson (@DKThomp) December 3, 2019

Ducks, bruh https://t.co/YGVAZc8f6L— Charles P. Pierce (@CharlesPPierce) December 4, 2019

I never realized Diamandis was such a clown.

Wow, this is amazing (and I so don't mean than in a good way). Even for a jaded hyperloop veteran like me, this is awful.

Showed up in my Google news feed and I couldn't help myself from clicking. @trnsprtst @RyanDeto https://t.co/0iYgU0f4t2— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 8, 2019

Check out this exchange https://t.co/yk6aaIVSM7— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 8, 2019

Money spent on ads so far:

Steyer: $47M

Bloomberg: $39M (in two weeks!!!))

All other Democrats combined: $15Mhttps://t.co/YZkZ6fbAux pic.twitter.com/U2DXojGiBB— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) December 7, 2019

“Juicero candidates” is such a great coinage, @dceiver is a king https://t.co/S9kgHH6u7h— Dave Weigel (@daveweigel) December 7, 2019

I didn’t know this but it’s in there and it’s insane. You’re required to work to get food stamps, but are ineligible if you have a car worth more than $2,250 you use to commute to work. Which is necessary to work if you don’t live on a bus route. https://t.co/4ZnL63iUUG pic.twitter.com/RVLWFXPDBD— Daniel J. Willis (@BayAreaData) December 6, 2019

"Isn’t it weird that a blogger has done the best work on comparative construction costs? New York plans to spend billions on railway & subway expansion. If better research could cut costs by 1%, it would be worth spending tens of millions on that research"https://t.co/OvLQjoceoI— John Arnold (@JohnArnoldFndtn) December 6, 2019

And a CEO with a history of making... let's call them questionable claims.https://t.co/C0A2vXxWEp— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) December 6, 2019

And, after that, you have to check out this, the ultimate Peloton thread.

Love putting my Peloton bike in the most striking area of my ultra-modern $3 million house— Clue Heywood (@ClueHeywood) January 28, 2019

Monday, December 9, 2019

What if Mayor Pete is HermanCainHermanCainHermanCain?

I've been meaning to write this up for quite a while, but it keeps getting put off and I'm afraid if I don't get something quick off, events may overtake us again. I'll try to come back to this if we get a chance.

Those who followed our comments on the 2016 may remember how various pundits (especially Nate Cohn) truly, deeply, desperately wanted to convince us and, more to the point themselves, that Donald Trump was just another Herman Cain and his polls numbers would fall just as quickly.

The analogy never made any sense with Trump, but the idea of an HC3, someone who emerges from the middle of the pack for little apparent reason, seems to be on the verge of challenging the leading candidates only to have that surge evaporate, can be useful.

My take on HC3s is that it's basically a mix of symmetry breaking and a Keynesian beauty contest. Voters are dissatisfied or, at least, uncomfortable with the front runners. As the decision point approaches, second and third tier choices are reexamined.with the considerably lower standard of being an acceptable alternative. Eventually this process converges on a candidate, at which point the scrutiny increases and the bloom is off the rose.

I'm not saying that Pete Buttigieg is a Herman Cain (I'm not even saying Herman Cain was a Herman Cain), but so far, I don't know that I've heard any supporter describe Buttigieg in positive rather than non-negative terms, and that is generally not a good sign.

Those who followed our comments on the 2016 may remember how various pundits (especially Nate Cohn) truly, deeply, desperately wanted to convince us and, more to the point themselves, that Donald Trump was just another Herman Cain and his polls numbers would fall just as quickly.

The analogy never made any sense with Trump, but the idea of an HC3, someone who emerges from the middle of the pack for little apparent reason, seems to be on the verge of challenging the leading candidates only to have that surge evaporate, can be useful.

My take on HC3s is that it's basically a mix of symmetry breaking and a Keynesian beauty contest. Voters are dissatisfied or, at least, uncomfortable with the front runners. As the decision point approaches, second and third tier choices are reexamined.with the considerably lower standard of being an acceptable alternative. Eventually this process converges on a candidate, at which point the scrutiny increases and the bloom is off the rose.

I'm not saying that Pete Buttigieg is a Herman Cain (I'm not even saying Herman Cain was a Herman Cain), but so far, I don't know that I've heard any supporter describe Buttigieg in positive rather than non-negative terms, and that is generally not a good sign.

Friday, December 6, 2019

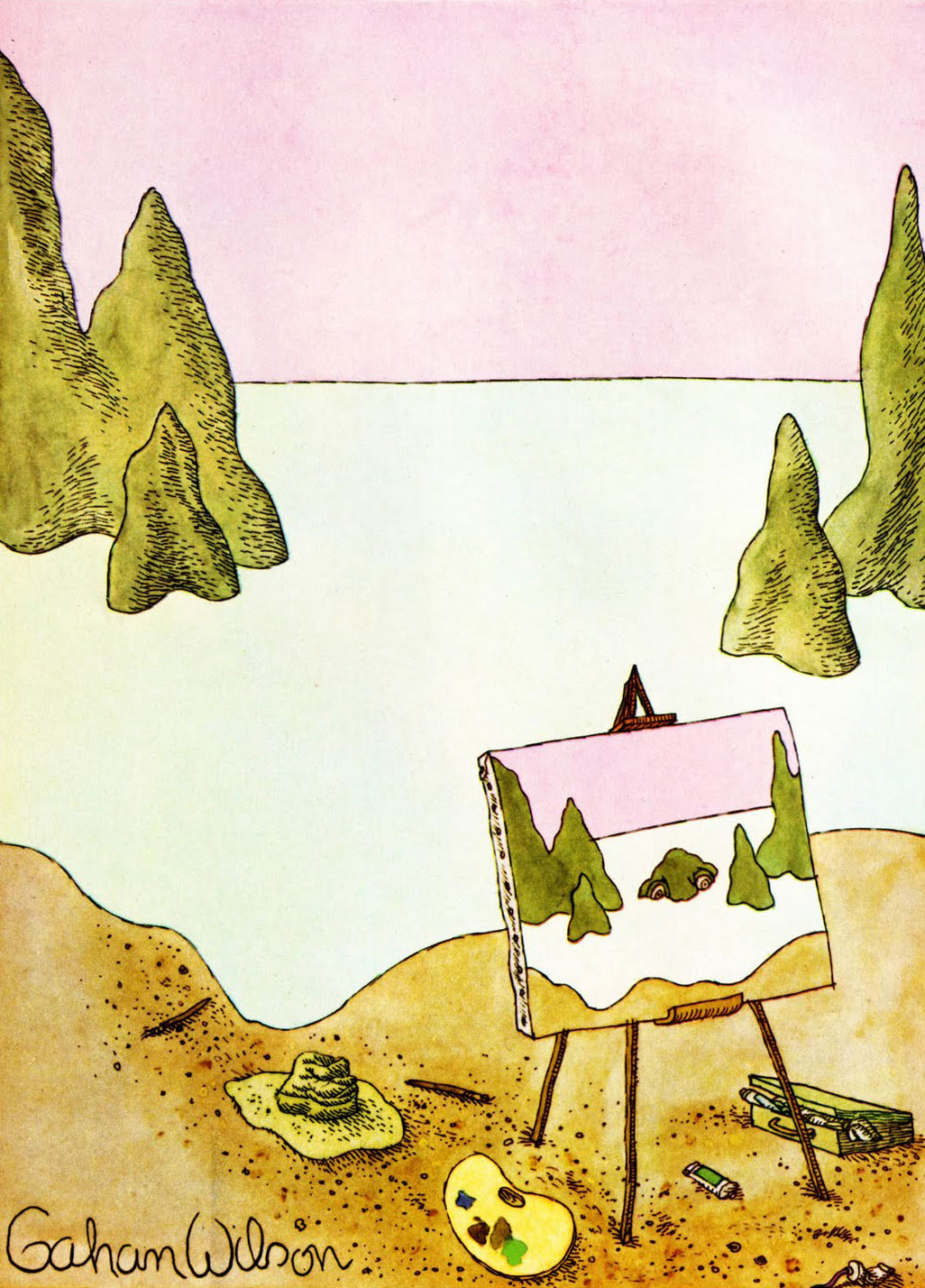

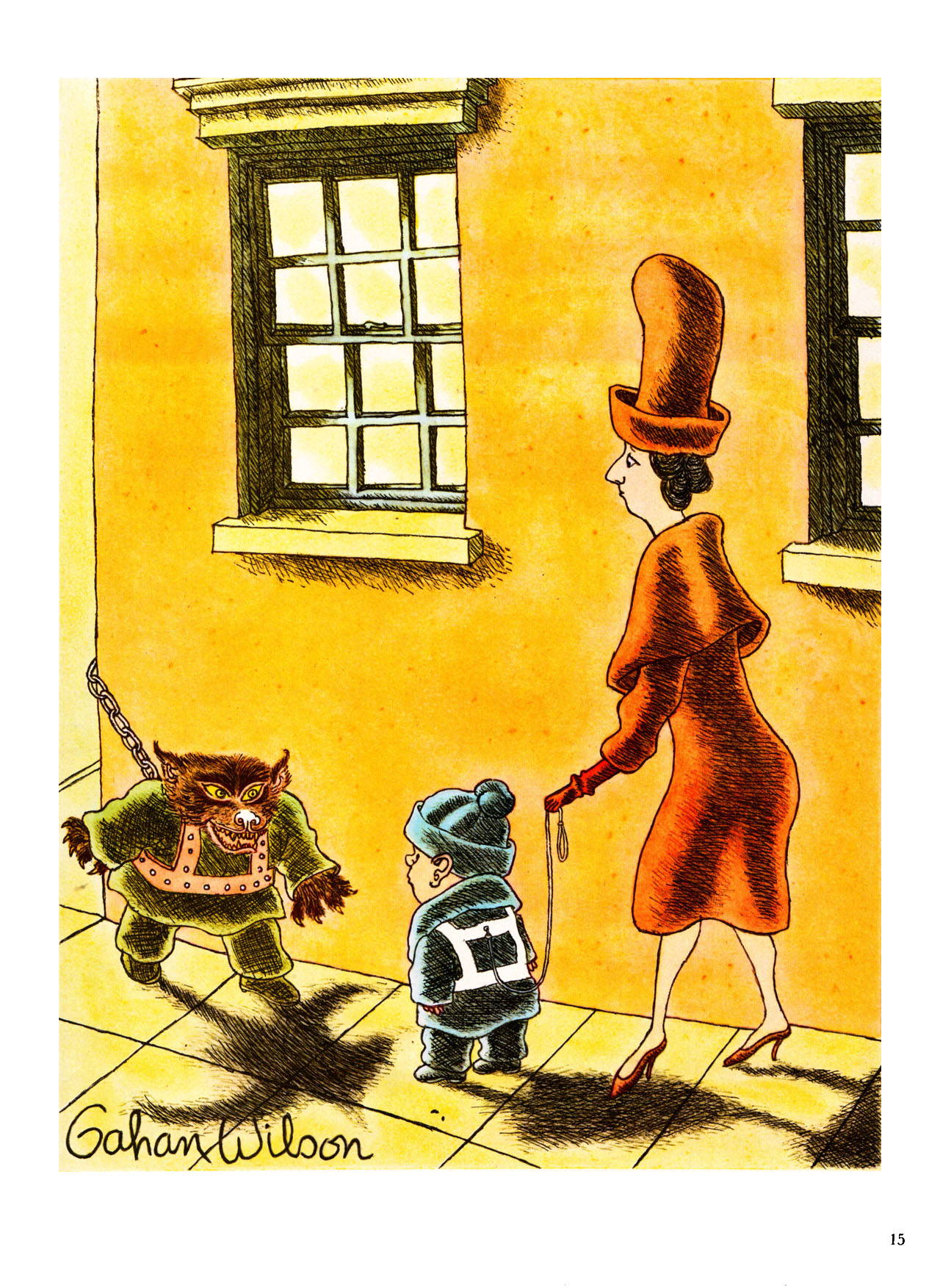

"I paint what I see" -- RIP Gahan Wilson

Gahan Allen Wilson (February 18, 1930 – November 21, 2019)

Strange to think that of Addams, Wilson and Larson, only the first has remained current and, in his case, only because of misplaced nostalgia for a not-too-successful 60s sitcom.

Strange to think that of Addams, Wilson and Larson, only the first has remained current and, in his case, only because of misplaced nostalgia for a not-too-successful 60s sitcom.

Thursday, December 5, 2019

If you built your Potemkin village entirely out of houses of cards

For a while now, we've been working toward a theory of how VC culture and practices can actually undermine innovation, perhaps even to the extent that it's a net drag on progress and real economic growth. This article by Peter Elstrom fills in a lot of the remaining questions in that theory.

A couple of points I want to underline in the following.

The growth fetish plays a major role in this story. We've been chipping away at this ages, but the quick version is that, while the right kind of growth is obviously desirable, it tends to be overvalued by 21st century investors. The fetish is particularly dangerous when it drives companies to make otherwise pointless acquisitions. I'm saving the best example of that (Oyo's real estate purchases) for another post.

I hadn't realized the extent that accounting tricks figured into SoftBank's strategy. I don't pretend to follow the subtleties but I am pretty sure this is bad.

[emphasis added]

A couple of points I want to underline in the following.

The growth fetish plays a major role in this story. We've been chipping away at this ages, but the quick version is that, while the right kind of growth is obviously desirable, it tends to be overvalued by 21st century investors. The fetish is particularly dangerous when it drives companies to make otherwise pointless acquisitions. I'm saving the best example of that (Oyo's real estate purchases) for another post.

I hadn't realized the extent that accounting tricks figured into SoftBank's strategy. I don't pretend to follow the subtleties but I am pretty sure this is bad.

[emphasis added]

In early 2018, the founders of Chinese artificial intelligence startup SenseTime Group Ltd. flew to Tokyo to see billionaire investor Masayoshi Son. As they entered the offices, Chief Executive Officer Xu Li was hoping to persuade the head of SoftBank Group to invest $200 million in his three-year-old startup.

A third of the way into the presentation, Son interrupted to say he wanted to put in $1 billion. A few minutes later, Son suggested $2 billion. Turning to the roomful of SoftBank managers, Son said this was the kind of AI company he’d been looking for. “Why are you only telling me about them now?” he asked, according to one person in the room.

In the end, SoftBank invested $1.2 billion, helping to transform SenseTime into the world’s most valuable AI startup. The young company’s valuation hit $7.5 billion this year.

That investment model is now under fire after Son, 62, boosted the equity in office-sharing startup WeWork only to see it plummet as investors balked at enormous losses and troublesome governance. Indeed, SoftBank has participated, along with other investors, in scores of fundraisings that have added a total of more than $150 billion to the value of private companies, according to Bloomberg calculations. Among its deals are the world’s top two startups—ByteDance Inc. valued at $75 billion and Didi Chuxing Inc. at about $56 billion. In some cases, SoftBank’s involvement in multiple funding rounds helped drive up valuations that resulted in paper profits for Son’s company.

The WeWork fiasco raises questions about such numbers. The co-working startup’s valuation crested at $47 billion this year with SoftBank’s investment, then plummeted to $7.8 billion in a bailout engineered by Son. WeWork is slashing jobs and scaling back operations.

“WeWork is not just a mistake, it is a signal of weakness in the whole model,” said Aswath Damodaran, a professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business, who has written four books on valuing businesses. “If you screwed up that valuation so badly, what about all of the other companies in your portfolio?”

SoftBank said WeWork is an exception rather than a symptom of broader problems, and it has learned from the experience.

Since unveiling his $100 billion Vision Fund in 2016, Son has become the most active tech investor on the planet, pouring money into more than 80 companies. That helped create a bumper crop of unicorns, more than 300 startups priced at $1 billion or greater, according to the research firm CB Insights.

What’s not as well understood is the incentive Son has to keep valuations rising. When SoftBank buys shares in a startup and then invests again at a higher valuation, Son says he has made a profit. That is legal under accounting standards, but SoftBank receives no money. The only change is that SoftBank has boosted the value of its original stake from, say, $1 billion to $2 billion by raising the value of the startup. In SoftBank’s income statements and return calculations, at least some of the additional $1 billion can be counted as profit.

“They pump up valuations to get higher returns to look good to investors,” says Eric Schiffer, chief executive officer of Patriarch Organization, a Los Angeles-based private equity fund. “That kind of fundraising apparatus is essentially unicorn porn.”

SoftBank said its accounting complies with all standards and is consistent with widely accepted practices. As for startup valuations, it said it is not determining them on its own and invests with experienced firms such as Sequoia Capital and Temasek Holdings Pte. “Our valuations have been validated by more than 120 sophisticated investors who’ve invested alongside and after us,” Navneet Govil, chief financial officer of SB Investment Advisers, the entity that manages the Vision Fund, said in a statement.

...

But the profits SoftBank booked were mostly on paper. In the first fiscal year, unrealized gains on investment valuations accounted for essentially all the stated income for the Vision and Delta funds. In the most recent fiscal year, unrealized gains on valuations amounted to 1 trillion yen, while realized gains—like the sale of India e-commerce giant Flipkart to Walmart Inc.—totaled less than 300 billion yen.

Wednesday, December 4, 2019

These stories are a lot funnier when the victims are Silicon Valley VCs and the Saudi sovereign wealth fund

We could have a long philosophical conversation about the distinction between a security based on records on a secured server and one based on records stored in a blockchain. For now though, I just wanted to point out familiar all of this sounds to anyone who has been following WeWork and Uber and all of the other unicorns. The same suspension of disbelief, power of positive (and fear of negative) thinking, next-big-thingism, fear of missing out.

The main difference is that the people who fell for WeWork and Theranos were supposed to know better.

From the BBC:

The main difference is that the people who fell for WeWork and Theranos were supposed to know better.

From the BBC:

But there was something wrong. In early October 2016 - four months after Dr Ruja's London appearance - a blockchain expert called Bjorn Bjercke was called by a recruitment agent, with a curious job offer. A cryptocurrency start-up from Bulgaria was looking for a chief technical officer. Bjercke would get an apartment and a car - and an attractive annual salary of about £250,000.

"I was thinking: 'What is my job going to be? What are the things that I'm going to have to do for this company?'" he recalls.

"And he said: 'Well, first of all, they need a blockchain. They don't have a blockchain today.'

"I said: 'What? You told me it was a cryptocurrency company.'"

The agent replied that this was correct. It was a cryptocurrency company, and it had been running for a while - but it didn't have a blockchain. "So we need you to build a blockchain," he went on.

"What's the name of the company?" asked Bjercke.

"It's OneCoin."

...

Investors often told us that what drew them in initially was the fear that they would miss out on the next big thing. They'd read, with envy, the stories of people striking gold with Bitcoin and thought OneCoin was a second chance. Many were struck by the personality and persuasiveness of the "visionary" Dr Ruja. Investors might not have understood the technology, but they could see her talking to huge audiences, or at the Economist conference. They were shown photographs of her numerous degrees, and copies of Forbes magazine with her portrait on the front cover.

The degrees are genuine. The Forbes cover isn't: it was actually an inside cover - a paid-for advertisement - from Forbes Bulgaria, but once the real cover was ripped off, it looked impressive.

[Also an ex-McKinsey consultant. That may be my favorite detail. -- MP]

But it seems it's not just the promise of riches that keeps people believing. After Jen McAdam invested into OneCoin she was constantly told she was part of the OneCoin "family". She was entered into a Whatsapp group, with its own "leader" who disseminated information from the headquarters in Sofia. And McAdam's leader prepared her carefully for conversations with OneCoin sceptics. "You're told not to believe anything from the 'outside world'," she recalls. "That's what they call it. 'Haters' - Bitcoiners are 'haters'. Even Google - 'Don't listen to Google!'" Any criticism or awkward questions were actively discouraged. "If you have any negativity you should not be in this group," she was told.

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Which could explain why it looks like a DeLorean hatchback -- Tuesday Tweets

The real reason for the unpainted stainless Cybertruck decision is *hushed voice* disruption.

This is unprecedented innovation, folks. Nobody has ever tried to justify this exact decision in misleading ways, only for the truth to end up in their obituary https://t.co/KaxUABkWrX pic.twitter.com/lTHL59xEZR— E.W. CYBERMEYER (@Tweetermeyer) November 27, 2019

🚨🚨🚨 (found it, yeeha)

That would mean that when Elon Musk announced the reveal on November 6, Tesla engineers had yet to start building the damn thinghttps://t.co/VY4OiIWVrU— Rob Forth (@robinivski) November 28, 2019

Always enjoy it when Josh Barro weighs in on a nepotism debate.

I dunno, why didn't Joe say anything to Hunter when he took the stupid job? It's Obama's job to clean up the mess now? https://t.co/SjRwwriSFv— Josh Barro (@jbarro) November 26, 2019

Worth it just for the use of the phrase "controlled detonation."

1/ Less than six months ago, on a joint call with Morgan Stanley's high yield analyst, Adam Jonas referred to Tesla as a "controlled detonation" and used the word "restructuring" numerous times. The high yield analyst spoke of the crushing burden of liabilities. https://t.co/3uwLnv5QS5— CrowPointPartners (@cppinvest) November 27, 2019

You have to be tenacious to investigate anything, but tenacity alone makes you a conspiracy theorist. The really hard part of investigative journalism is pursuing a story tenaciously while remaining open-minded about what the story actually is. If this sounds like a zen koan...— E.W. CYBERMEYER (@Tweetermeyer) November 30, 2019

So I did a deep dive into commas a few years ago and discovered that almost every comma rule you know was codified or invented by Strunk & White in 1918 or the editor of the New Yorker in 1935, and that's how I learned to stop worrying and love commas-as-rhythm. https://t.co/Ojo4yZd6L7— David Thomas Moore is still in the EU (@dtmooreeditor) November 26, 2019

We'll be revisiting this.

Hasn't happened yet, but political journalism in the US will have to rethink it's relationship to the Republican Party, as conspiracy thinking, attacks on the press, and, to use an academic term, making shit up become not what the GOP does, but what it is. https://t.co/p9QR4OCvwM— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) November 29, 2019

For the cult of personality thread.

Lou Dobbs: Trump is "already the greatest president. And if you look at any other president and what they are able to accomplish in 3 years, without a Congress, without the help of their own conference, their own party, it's extraordinary" pic.twitter.com/CmRO0sHCpG— Brendan Karet 🚮 (@bad_takes) November 27, 2019

Rick Perry 2015: “Let no one be mistaken - Donald Trump's candidacy is a cancer on conservatism, and it must be clearly diagnosed, excised and discarded.”

Rick Perry now: https://t.co/Q0dtbfUNzk— Adam Rubenstein (@RubensteinAdam) November 25, 2019

My question is how big is that 1/3 next to Trump's thin margin of victory?

—

John Harwood (@JohnJHarwood) November

27, 2019

My current rule. Adapted from @ThePlumLineGS.

All discussions of "Good lord, why are we so divided? America can't even agree on common facts" (very popular these days) should be framed instead as: how did the Republican Party arrive at this place? https://t.co/UCunJhK5qD— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) November 27, 2019

I wrote in Trumpocracy:

“The main benefit of controlling a modern bureaucratic state is not the power to persecute the innocent. It is the power to protect the guilty.” https://t.co/Re2fv4hpZL— David Frum (@davidfrum) November 25, 2019

If you read press coverage of the Democratic campaign, you'd get no sense at all that Democratic voters are quite happy with their field, even though those numbers are as high as they've ever been.— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) November 25, 2019

Monday, December 2, 2019

Perhaps the part about the laws of economics not applying should have been a tip off.

Excellent article by Gabriel Sherman who is definitely the kind of writer you'd want on this beat. There is, however, one theme I'd like to push back on. We hear a lot about how powerfully charismatic and incredibly persuasive company co-founder Adam Neumann was. How else would he convince men like Jamie Dimon that a laughably bad business plan was not only viable but would justify a valuation of almost fifty billion dollars?

The trouble with that explanation is that we've seen a remarkably large number of these masters of mesmerism recently. Think of all the companies which, in the past decade or so, have raised huge amounts of money based on pitches that collapsed immediately under even mild scrutiny. They can't all be the work of superhuman salesmen.

As an alternative, is it possible that the combination of a Randian worship of the wealthy, conditions that made it easier than ever to luck into great fortunes and the rise of the credulity driven hype economy have all made it easier to find gullible people with way too much money?

WeWork executives had long grown accustomed to Neumann’s belief that the laws of economics—even reality itself—didn’t apply to him. It was in the nature of unicorns that they bent reality, and that certainly had been true of WeWork. Fueled by $12 billion of venture capital and debt, Neumann grew WeWork in less than a decade from a single coworking outpost in SoHo into a 12,500-employee company with 500,000 users in 111 cities across 29 countries. But in 2018, WeWork had lost $2 billion and had a highly questionable business model—the company signed long-term leases and sublet space to freelancers and corporations on a short-term basis. Its valuation somehow kept rising.

The company’s valuation put Neumann’s net worth at $4.1 billion—and his spending more than kept pace. “It was Succession craziness,” a colleague said. Neumann was chauffeured around in a $100,000-plus Maybach sedan and traveled the world on a $60 million Gulfstream G650. As reported in the Wall Street Journal, he and his wife, Rebekah Paltrow Neumann—Gwyneth’s first cousin—spent $90 million on a collection of six homes that included a 6000-square-foot Gramercy condo, a 60-acre estate in Westchester County, a pair of Hamptons houses and a $21 million mansion in the Bay Area that features a room shaped like a guitar. They employed a squadron of nannies for their five children, two personal assistants, and a chef. “Adam went through money like water,” a former executive said.

In a way, the spending made sense, because Neumann himself was the product. He pitched himself to investors as a gatekeeper to the rising generation. A new way of working. A new way of living. Work was 24/7, coworkers were friends, office was home, work was life. For baby boomers who experienced office life as cubicles and bad coffee, his message was irresistible. “Every investor who walked through was sold,” a WeWork executive told me. They saw Neumann as a millennial prophet who did shots of Don Julio during meetings while preaching about the dawn of a new corporate culture, one in which the beer and kombucha flowed and MacBook-toting employees would love coming to work. After sitting with Neumann in his office, outfitted with a Peloton bike, infrared sauna, and cold water plunge, Steve Jobs biographer Walter Isaacson told Fast Company that Neumann reminded him of the Apple cofounder. Neumann later told colleagues that Isaacson might write his biography. (Isaacson never considered writing such a book.)

Through a combination of egomaniacal glamour and millennial mysticism, the Neumanns sold WeWork not merely as a real estate play. It wasn’t even a tech company (though he said it should be valued as such). It was a movement, complete with its own catechisms (“What is your superpower?” was one). Adam said WeWork existed to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” The company would allow people to “make a life and not just a living.” It was even capable of solving the world’s thorniest problems. Last summer, some WeWork executives were shocked to discover Neumann was working on Jared Kushner’s Mideast peace effort. According to two sources, Neumann assigned WeWork’s director of development, Roni Bahar, to hire an advertising firm to produce a slick video for Kushner that would showcase what an economically transformed West Bank and Gaza would look like. (Bahar told me he only advised on the video and no WeWork resources were used.) Kushner showed a version of the video during his speech at the White House’s peace conference in Bahrain last summer.

To a passel of geezer capitalists, this was too big to miss, even if they didn’t fully understand it—possibly, not understanding it was the point. Rupert Murdoch, Sir Martin Sorrell, and Larry Silverstein all took meetings. Mort Zuckerman, the billionaire cofounder of developer Boston Properties, told a real estate executive shortly after WeWork launched that Neumann was creating the future of work. Zuckerman soon offered to buy WeWork for $500 million. (Neumann declined the deal but accepted a $2 million investment from Zuckerman.) “Adam was probably the best salesman of all time,” a former WeWork executive told me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)