Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, August 23, 2019

Let's kick the weekend of right

Cabell "Cab" Calloway III was one of the most dynamic entertainers of the 20th Century, but this was one time he couldn't dominate the stage.

Not sure why this Nicholas Brothers number came to mind or how I can tie it into any of our threads, other than with the all-purpose reason that everyone should see this at least once.

Thursday, August 22, 2019

"A public-private partnership" ... nothing ominous about that phrase

Just so we're clear. We are edging closer to see hundreds of millions, perhaps billions of tax dollars go to highly dubious projects, not because the promoters have introduced major technological breakthroughs or have proposed well thought-out plans, but because they managed to wait out their critics, counting on reporters' eagerness to believe a too-good-to-be-true story and reluctance to do the hard work of digging into the complex engineering details. Yes, there have been exceptions, but by now they are all but drowned out by the hype and bullshit.

Ryan Kelly, Head of Marketing and Communications for Virgin Hyperloop One, told CU that the next major step is to build what the company calls a “certification track.”One more thing.

That track would be a little over seven miles long and would enable the company to go beyond what it has achieved at its privately-funded test track. That means putting people in the pods for the first time, developing a switching system that would allow multiple pods to travel in the tube at the same time [I'm not sure about this part. I think the switching system may be for allowing the pods to take different forking paths. -- MP], and seeing if a pod can safely travel through the tube at a much greater speed than it has so far (to achieve the kind of travel times the company has promised, pods would have to travel more than twice as fast as the XP-1 did in Nevada).

...

Officials in India recently announced that a proposed Virgin Hyperloop One project connecting Pune and Mumbai will be moving into the procurement phase, although Kelly said that the company has not yet decided where to build the certification track.

“Whether India is going to be able to provide the support in order to certify globally (is still unknown)…the U.S. I think has a better opportunity to potentially do that and so that’s why states are kind of vying for that now,” he said, adding that the company estimates the cost of building the track in India at “about $500 million.”

“Our timeline here is that we want to have the certification track up and running by 2024, somewhere in the world, and we want (the Hyperloop) certified and ready to go,” Kelly added, explaining that, even if the track is not built in Ohio, the planning and procurement process for the Chicago route could continue for the next five years, and, once the technology is certified and approved, “we break ground.”

An estimate of the overall cost of a Hyperloop connecting Chicago, Columbus and Pittsburgh has yet to be released, but a study by the Colorado Department of Transportation put a $24 billion price tag on a 325-mile network in that state.

As for who would pay for the $500 million certification track needed to prove the technology works, Kelly said “we’re looking at a public-private partnership; (there will be) private investment, but whatever that public agreement looks like would have to be negotiated case-by-case…so, we’re also looking for, obviously, what’s the best offer that we’re going to get to make this happen?”

2017

"Virgin Hyperloop One ... says it wants to have three operating hyperloop systems by 2021"

2019

"Our timeline here is that we want to have the certification track up and running by 2024"— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 10, 2019

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

One of the advantages of having been blogging this long is that when someone says something really stupid, you've probably already written a rebuttal

For example, say that a Washington Post columnist/torture enthusiast/Manafort minion (or Stone crony -- I'm not entirely clear on that point) starts pontificating about kids these days...

I don't have to spend my evening writing a post explaining why you can safely skip all of these op-eds about millennials. I can just dip into the archives.

First, there is the practice of making a sweeping statement about a "generation" when one is actually making a claim about a trend. This isn't just wrong; it is the opposite of right. The very concept of a generation implies a relatively stable state of affairs for a given group of people over an extended period of time. If people born in 1991 are more likely to do something that people born in 1992 and people born in 1992 are more likely to do it than people born in 1993 and so on, discussing the behavior in terms of a generation makes no sense whatsoever.

We see this constantly in articles about "the millennial generation" (and while we are on the subject, when you see "the millennial generation," you can replace "may be about to encounter serious bullshit" with "are almost certainly about to encounter serious bullshit"). Often these "What's wrong with millennial's?" think pieces manage multiple layers of crap, taking a trend that is not actually a trend and then mislabeling it as a trait of a generation that's not a generation.

How often does the very concept of a generation make sense? Think about what we're saying when we use the term. In order for it to be meaningful, people born in a given 10 to 20 year interval have to have more in common with each other than with people in the preceding and following generations, even in cases where the inter-generational age difference is less than the intra-generational age difference.

Consider the conditions where that would be a reasonable assumption. You would generally need society to be at one extreme for an extended period of time, then suddenly swing to another. You can certainly find big events that produce this kind of change. In Europe, for instance, the first world war marked a clear dividing line for the generations.

(It is important to note that the term "clear" is somewhat relative here. There is always going to be a certain fuzziness with cutoff points when talking about generations, even with the most abrupt shifts. Societies don't change overnight and individuals seldom fall into the groups. Nonetheless, there are cases where the idea of a dividing line is at least a useful fiction.)

In terms of living Americans, what periods can we meaningfully associate with distinct generations? I'd argue that there are only two: those who spent a significant portion of their formative years during the Depression and WWII; and those who came of age in the Post-War/Youth Movement/Vietnam era.

Obviously, there are all sorts of caveats that should be made here, but the idea that Americans born in the mid-20s and mid-30s would share some common framework is a justifiable assumption, as is the idea that those born in the mid-40s and mid-50s would as well. Perhaps more importantly, it is also reasonable to talk about the sharp differences between people born in the mid-30s and the mid-40s.

There are a lot of interesting insights you can derive from looking at these two generations, but, as far as I can see, attempts to arbitrarily group Americans born after, say, 1958 (which would have them turning 18 after the fall of Saigon) is largely a waste of time and is often profoundly misleading. The world continues to change rapidly, just not in a way that lends itself toward simple labels and categories.

Maybe @marcthiessen can share some of his war stories about sewers during his tour of duty at Black Manafort. It must have been harrowing.— Iván Cavero Belaunde (@ivanski) August 10, 2019

I don't have to spend my evening writing a post explaining why you can safely skip all of these op-eds about millennials. I can just dip into the archives.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Among living Americans, there are only two "generations"

"The ________ Generation” has long been one of those red-flag phrases, a strong indicator that you may be about to encounter serious bullshit. There are occasions when it makes sense to group together people born during a specified period of 10 to 20 years, but those occasions are fairly rare and make up a vanishingly small part of the usage of the concept.First, there is the practice of making a sweeping statement about a "generation" when one is actually making a claim about a trend. This isn't just wrong; it is the opposite of right. The very concept of a generation implies a relatively stable state of affairs for a given group of people over an extended period of time. If people born in 1991 are more likely to do something that people born in 1992 and people born in 1992 are more likely to do it than people born in 1993 and so on, discussing the behavior in terms of a generation makes no sense whatsoever.

We see this constantly in articles about "the millennial generation" (and while we are on the subject, when you see "the millennial generation," you can replace "may be about to encounter serious bullshit" with "are almost certainly about to encounter serious bullshit"). Often these "What's wrong with millennial's?" think pieces manage multiple layers of crap, taking a trend that is not actually a trend and then mislabeling it as a trait of a generation that's not a generation.

How often does the very concept of a generation make sense? Think about what we're saying when we use the term. In order for it to be meaningful, people born in a given 10 to 20 year interval have to have more in common with each other than with people in the preceding and following generations, even in cases where the inter-generational age difference is less than the intra-generational age difference.

Consider the conditions where that would be a reasonable assumption. You would generally need society to be at one extreme for an extended period of time, then suddenly swing to another. You can certainly find big events that produce this kind of change. In Europe, for instance, the first world war marked a clear dividing line for the generations.

(It is important to note that the term "clear" is somewhat relative here. There is always going to be a certain fuzziness with cutoff points when talking about generations, even with the most abrupt shifts. Societies don't change overnight and individuals seldom fall into the groups. Nonetheless, there are cases where the idea of a dividing line is at least a useful fiction.)

In terms of living Americans, what periods can we meaningfully associate with distinct generations? I'd argue that there are only two: those who spent a significant portion of their formative years during the Depression and WWII; and those who came of age in the Post-War/Youth Movement/Vietnam era.

Obviously, there are all sorts of caveats that should be made here, but the idea that Americans born in the mid-20s and mid-30s would share some common framework is a justifiable assumption, as is the idea that those born in the mid-40s and mid-50s would as well. Perhaps more importantly, it is also reasonable to talk about the sharp differences between people born in the mid-30s and the mid-40s.

There are a lot of interesting insights you can derive from looking at these two generations, but, as far as I can see, attempts to arbitrarily group Americans born after, say, 1958 (which would have them turning 18 after the fall of Saigon) is largely a waste of time and is often profoundly misleading. The world continues to change rapidly, just not in a way that lends itself toward simple labels and categories.

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

Kudlow is as close as you'll find to a human knight/knave puzzle.

Point 1/ https://t.co/PdX0Qe2VPn— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) August 18, 2019

that latter one was from Dec. 2007. Of course we all make bad predictions — but Kudlow is *always* wrong 3/— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) August 18, 2019

No matter how many experts try to inject a note of reality, the narrative always reverts to a standard post-war sci-fi fantasy. @torstenkathke— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 13, 2019

The case for addressing climate change is so overwhelming that exaggeration can't add much to the support; it can only erode our credibility. @Sheril_— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 15, 2019

The "we're all doomed" crowd is not only undercutting serious efforts to fight climate change, they're also dabbling in bad science (like anti-vaxxer talking points).https://t.co/BjqZfSuJV9— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 15, 2019

Monday, August 19, 2019

The essential takedown of the Mars delusion

If you have followed this story at all, you have to read this article by George Dvorsky.

It goes on from there, demolishing the whole ridiculous sham. If we had a functional discourse, this would kill the topic of imminent Martian colonies and let us move on to a serious conversation about the exploration of space.

Of course, we don't have a functional discourse.

This won't kill the topic.

We won't move on.

Respectable publications like the Atlantic will continue to run articles like CSI:Mars. Elon Musk will continue to be treated as a tech messiah. Actual breakthroughs like airbreathing rockets will go largely unnoticed.

And we will all continue getting dumber by the day.

The Red Planet is a cold, dead place, with an atmosphere about 100 times thinner than Earth’s. The paltry amount of air that does exist on Mars is primarily composed of noxious carbon dioxide, which does little to protect the surface from the Sun’s harmful rays. Air pressure on Mars is very low; at 600 Pascals, it’s only about 0.6 percent that of Earth. You might as well be exposed to the vacuum of space, resulting in a severe form of the bends—including ruptured lungs, dangerously swollen skin and body tissue, and ultimately death. The thin atmosphere also means that heat cannot be retained at the surface. The average temperature on Mars is -81 degrees Fahrenheit (-63 degrees Celsius), with temperatures dropping as low as -195 degrees F (-126 degrees C). By contrast, the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth was at Vostok Station in Antarctica, at -128 degrees F (-89 degrees C) on June 23, 1982. Once temperatures get below the -40 degrees F/C mark, people who aren’t properly dressed for the occasion can expect hypothermia to set in within about five to seven minutes.

Mars also has less mass than is typically appreciated. Gravity on the Red Planet is 0.375 that of Earth’s, which means a 180-pound person on Earth would weigh a scant 68 pounds on Mars. While that might sound appealing, this low-gravity environment would likely wreak havoc to human health in the long term, and possibly have negative impacts on human fertility.

...

Pioneering astronautics engineer Louis Friedman, co-founder of the Planetary Society and author of Human Spaceflight: From Mars to the Stars, likens this unfounded enthusiasm to the unfulfilled visions proposed during the 1940s and 1950s.

“Back then, cover stories of magazines like Popular Mechanics and Popular Science showed colonies under the oceans and in the Antarctic,” Friedman told Gizmodo. The feeling was that humans would find a way to occupy every nook and cranny of the planet, no matter how challenging or inhospitable, he said. “But this just hasn’t happened. We make occasional visits to Antarctica and we even have some bases there, but that’s about it. Under the oceans it’s even worse, with some limited human operations, but in reality it’s really very, very little.” As for human colonies in either of these environments, not so much. In fact, not at all, despite the relative ease at which we could achieve this.

It goes on from there, demolishing the whole ridiculous sham. If we had a functional discourse, this would kill the topic of imminent Martian colonies and let us move on to a serious conversation about the exploration of space.

Of course, we don't have a functional discourse.

This won't kill the topic.

We won't move on.

Respectable publications like the Atlantic will continue to run articles like CSI:Mars. Elon Musk will continue to be treated as a tech messiah. Actual breakthroughs like airbreathing rockets will go largely unnoticed.

And we will all continue getting dumber by the day.

Friday, August 16, 2019

Thursday, August 15, 2019

After following Uber and Lyft, it's almost refreshing to find a tech company that's competent at being evil

Back in Arkansas, we used to talk about Wal-Mart "killing a town twice." The company would open a store in a small town, drive the local merchants out of business, then close that location so that the residents would have to do their shopping at the Wal-Mart in the next town ten or fifteen miles down the road.

The underlying logic remains the same. If you have market dominance and deep pockets, your quickest path to higher profit margins is to drive the little guys out of business. The complete lack of shame does, however, seem to be a bit of a 21st Century innovation.

From Gizmodo.

The underlying logic remains the same. If you have market dominance and deep pockets, your quickest path to higher profit margins is to drive the little guys out of business. The complete lack of shame does, however, seem to be a bit of a 21st Century innovation.

From Gizmodo.

Citing interviews with merchants of the e-commerce giant, as well as internal sent alerts to those individuals, Bloomberg reported Monday that Amazon is effectively penalizing its sellers if it finds that their products are being offered for a lower on rival websites. If it finds competitive pricing elsewhere, Amazon alerts a merchant with price comparisons between the two marketplaces and informs them that their product has essentially been demoted by Amazon’s system and will be more difficult to find or purchase on its site, according to the report.

Bloomberg said the practice began in 2017, but added that alerts have been more frequent as Amazon works to maintain its dominance in the e-commerce space.

The way that Amazon works to undermine sales for merchants of competitively priced products is to remove the “Buy Now” button that appears to the right of products on its platform, Bloomberg reported. While the product can still technically be purchased, it makes the product more difficult for shoppers and can hurt a seller’s bottom line. It also means that sellers are being forced to adjust their prices on rival marketplaces, which can be a blow to any attempts to offset the huge chunk of change that Amazon takes for itself just to list merchant products on its site.

“Amazon works hard to keep prices low for both customers and sellers. We have very competitive fees for sellers and we make significant investments on their behalf to continually improve our store and empower their businesses,” a spokesperson told Gizmodo in a statement by email. “In our store, we feature the offer that predicts the best shopping experience for the customer based on a number of factors including price and delivery speed. Sellers have full control of their own prices both on and off Amazon, and we help them maximize their sales in our store by providing them insights on how to be the featured offer.”

Of course, Amazon controlled just under half of the e-commerce market as of last year, and it only gets bigger every day—meaning online sellers have few places to go to find a customer. And with online markets hollowing out the brick and mortar space, online sellers don’t really have a choice to not be online. This kind of practice might keep prices down for consumers and users glued to Amazon dot com, but it does not create healthy competition or a sustainable marketplace for sellers.

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Agent-based simulations and horse-race journalism

[This was never my area of expertise, and what little I once knew I've mostly forgotten. Since lots of our regular readers are experts on this sort of things, I welcome criticism but I hope you'll be gentle.]

I tried a little project of my own back in the early 2000s. One of these days, I'd like to revisit the topic here and talk about what I had in mind and how quixotic the whole thing was, but for now there's one aspect of it that has become particularly relevant so here's a very quick overview so I can get to the main point.

Imagine you have an agent-based simulation with a fixed number of iterations and a fixed number of runs. You randomly place the agents on a landscape with multiple dimensions and multiple optima and have them each perform gradient searches. Now we add one wrinkle. Each agent is aware of the position of at least one other agent and will move toward either the highest point in its search radius unless another searcher it is in communication with has a higher position in which case it heads toward that one.

What happens to average height when we add lines of communication to the matrix? At one extreme where each searcher is only in contact with one other, you are much more likely to have one of them find the global optima but most will be left behind. At the other extreme, if everyone is in contact with everyone, there is a far greater chance of converging on a substandard local optima. Every time I ran a set of simulations, I got the same U-shaped curve with the best results coming from a high but not too high level of communication.

It is always dangerous to extend these abstract ideas derived from artificial scenarios to the real world, but there are some fairly obvious conclusions we can draw. What if we think of the primary process in similar terms? Each voter is doing an optimization search, bringing in information on their own and trying to determine the best choice, but at the same time, they are also weighing the opinions of others performing the same search.

Given this framework, what is the optimal level of communication between voters via the polls? At what point does the frequency of polling reach a level where it makes it more likely for voters to converge on a sub-optimal choice? I'm pretty sure we've passed it.

I tried a little project of my own back in the early 2000s. One of these days, I'd like to revisit the topic here and talk about what I had in mind and how quixotic the whole thing was, but for now there's one aspect of it that has become particularly relevant so here's a very quick overview so I can get to the main point.

Imagine you have an agent-based simulation with a fixed number of iterations and a fixed number of runs. You randomly place the agents on a landscape with multiple dimensions and multiple optima and have them each perform gradient searches. Now we add one wrinkle. Each agent is aware of the position of at least one other agent and will move toward either the highest point in its search radius unless another searcher it is in communication with has a higher position in which case it heads toward that one.

What happens to average height when we add lines of communication to the matrix? At one extreme where each searcher is only in contact with one other, you are much more likely to have one of them find the global optima but most will be left behind. At the other extreme, if everyone is in contact with everyone, there is a far greater chance of converging on a substandard local optima. Every time I ran a set of simulations, I got the same U-shaped curve with the best results coming from a high but not too high level of communication.

It is always dangerous to extend these abstract ideas derived from artificial scenarios to the real world, but there are some fairly obvious conclusions we can draw. What if we think of the primary process in similar terms? Each voter is doing an optimization search, bringing in information on their own and trying to determine the best choice, but at the same time, they are also weighing the opinions of others performing the same search.

Given this framework, what is the optimal level of communication between voters via the polls? At what point does the frequency of polling reach a level where it makes it more likely for voters to converge on a sub-optimal choice? I'm pretty sure we've passed it.

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

These seem to stand on their own.

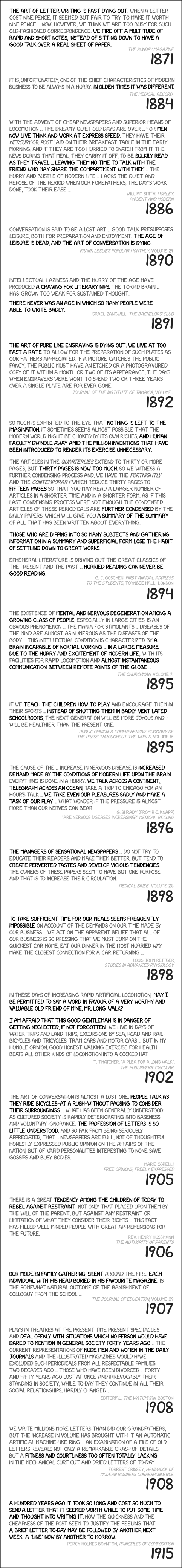

Humans love to socialize, it is a basic human need. When new technologies facilitate it, suddenly we call it an addiction. https://t.co/YuzjQJ8E4E— Pessimists Archive (@PessimistsArc) August 10, 2019

I know we've been over this one before, but I keep coming back to the traffic cop question. True level five should be able to handle a human directing traffic but it remains a tremendously challenging problem for AI.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 10, 2019

Here in Charleston it really doesn't matter when restaurants open or close because one day the entire city will be underwater, nothing will exist, and all our pain and suffering will disappear.

Eat Bubba Gump Shrimp.

Or don't. Because it's gone.https://t.co/0PLZm4Wk2s— The Post and Courier (@postandcourier) August 9, 2019

Spoiler alert: they mostly don't exist, despite Elon Musk talking about them constantly. https://t.co/LpbhwFHKPr— Timothy B. Lee (@binarybits) August 10, 2019

It still amazes me that we did any programming at at before we could look up code on Google.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 8, 2019

Since I'm now getting "there was never any hype" revisionism in my comments, some handy (but far from exhaustive) screenshots pic.twitter.com/OGI22iJiY5— Scott Lemieux (@LemieuxLGM) August 6, 2019

Are we entirely certain he was joking? https://t.co/rXk4P94FhH— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 10, 2019

Monday, August 12, 2019

Repost, repost, repost (I want to revisit this thread)

Monday, February 4, 2019

America is a country bitterly divided into two groups – – treatment and control.

The following would sound paranoid if it hadn't been so openly discussed by the leaders of the conservative movement in real time. At the risk of slightly oversimplifying, during the flush years of the Reagan administration, these leaders came up with a multipart plan to address the challenge of maintaining power in America while pursuing policies that lacked majority support.The plan included devoting resources to high value-to-cost races such as midterms and statehouses, gerrymandering and voter suppression, dominance of and greater freedom to use campaign money, a highly disciplined carrot and stick approach to the establishment media that played shrewdly on its weaknesses and biases, and a massive social engineering experiment.

The pundit class has always had a problem with acknowledging and honestly addressing the various aspects of this plan, but it is the last element which indicates the largest blind spot. Commentators and more embarrassingly even some political scientists have pushed a string of theories that don't come close to fitting the facts with at least one requiring that West Virginia be re-assigned to the Confederacy.

All of this flailing around might be excusable if there were not an obvious explanation that almost perfectly describes the data. At least on a high level, all you need to ask yourself is who got the treatment?

Yes, there are certainly complications and complexities that need to be addressed. We need to talk about why certain people respond better. We need to look at the various channels and mechanisms beyond media including Astroturfing and the corruption of many of the leaders of the evangelical movement (particularly those espousing prosperity gospel). We need to acknowledge that this is not a clean experiment and that there are multiple levels of selection effects to contend with.

Those details, while important, are secondary. For now, the point we need to focus on is that there is a remarkably strong correspondence between conservative media reaching critical mass and an area going deep red, pro-Trump.

Unquestionably, the causal arrows run both ways here and we should approach some of the more subtle questions with caution, but the highly simplified model – – conservative propaganda and disinformation are the primary drivers of the rise of the reactionary right – – does an extraordinarily good job in explaining the last decade and the reluctance of many commentators and researchers to embrace it is itself a social phenomenon worth studying.

Tuesday, February 5, 2019

Rational actors, stag hunts and the GOP

We have hit this idea in passing a few times in the past (particularly when discussing the Ponzi threshold), but I don't believe we've ever done a post on it. While there's nothing especially radical about the idea (it shows up in discussions of risk fairly frequently), it is different enough to require a conscious shift in thinking and, under certain circumstances, it can have radically different implications.Most of the time, we tend to think of rational behavior in terms of optimizing expected values, but it is sometimes useful to think in terms of maximizing the probability of being above or below a certain threshold. Consider the somewhat overly dramatic example of a man told that he will be killed by a loan shark if he doesn't have $5000 by the end of the day. In this case, putting all of his money on a long shot at the track might well be his most rational option.

You can almost certainly think of less extreme cases where you have used the same approach, trying to figure out the best way to ensure you had at least a certain amount of money in your checking account or had set aside enough for a mortgage payment.

Often, these two ways of thinking about rational behavior are interchangeable, but not always. Our degenerate gambler is one example, and I've previously argued that overvalued companies like Uber or Netflix are another, the one I've been thinking about a lot recently is the Republican Party and its relationship with Trump.

Without going into too much detail (these are subjects for future posts), one of the three or four major components of the conservative movement's strategy was a social engineering experiment designed to create a loyal and highly motivated base. The initiative worked fairly well for a while, but with the rise of the tea party and then the Trump wing, the leaders of the movement lost control of the faction they had created. (Have we done a post positing the innate instability of the Straussian model and other systems based on disinformation? I've lost track.)

In 2016, the Republican Party had put itself in the strange position of having what should have been their most reliable core voters fanatically loyal to someone completely indifferent to the interests of the party, someone who was capable of and temperamentally inclined to bringing the whole damn building down it forced out. Since then, I would argue that the best way of understanding the choices of those Republicans not deep in the cult of personality is to think of them optimizing against a shifting threshold.

Trump's 2016 victory was only possible because a number of things lined up exactly right, many of which were dependent on the complacency of Democratic voters, the press, and the political establishment. Repeating this victory in 2020 without the advantage of surprise would require Trump to have exceeded expectations and started to win over non-supporters. Even early in 2017, this seemed unlikely, so most establishment Republicans started optimizing for a soft landing, hoping to hold the house in 2018 while minimizing the damage from 2020. They did everything they could to delay investigations into Trump scandals, attempted to surround him with "grown-ups," and presented a unified front while taking advantage of what was likely to be there last time at the trough for a while.

Even shortly before the midterms, it became apparent that a soft landing was unlikely and the threshold shifted to hard landing. The idea of expanding on the Trump base was largely abandoned as were any attempts to restrain the president. The objective now was to maintain enough of a foundation to rebuild up on after things collapsed.

With recent events, particularly the shutdown, the threshold shifted again to party viability. Arguably the primary stated objective of the conservative movement has always been finding a way to maintain control in a democracy while promoting unpopular positions. This inevitably results in running on thinner and thinner margins. The current configuration of the movement has to make every vote count. This gives any significant faction of the base the power to cost the party any or all elections for the foreseeable future.

It is not at all clear how the GOP would fill the hole left by a defection of the anti-immigrant wing or of those voters who are personally committed to Trump regardless of policy. Having these two groups suddenly and unexpectedly at odds with each other (they had long appeared inseparable) is tremendously worrisome for Republicans, but even a unified base can't compensate for sufficiently unpopular policies. Another shutdown or the declaration of a state of emergency both appear to have the potential to damage the party's prospects not just in 2020 but in the following midterms and perhaps even 2024.

So far, the changes in optimal strategy associated with the shifting thresholds have been fairly subtle, but if the threshold drops below party viability, things get very different very quickly. We could and probably should frame this in terms of stag hunts and Nash equilibria but you don't need to know anything about game theory to understand that when a substantial number of people in and around the Republican Party establishment stop acting under the assumption that there will continue to be a Republican Party, then almost every other assumption we make about the way the party functions goes out the window.

Just to be clear, I'm not making predictions about what the chaos will look like; I'm saying you can't make predictions about it. A year from now we are likely to be in completely uncharted water and any pundit or analyst who makes confident data-based pronouncements about what will or won't happen is likely to lose a great deal of credibility.

Monday, February 11, 2019

Catharsis

Picking up from our previous post about approaching the rise of the Trump voter in terms of a social engineering experiment, one of the best indicators of epicyclic thinking is that each adjustment helps explain only one isolated aspect of the situation. In contrast, when introducing a good framework or mental model, most of what we see should suddenly make more sense. This applies not only to what happens but to how it happens.With that in mind, let's talk about something that has been largely absent from the various think pieces on the subject but which has great explanatory power and which rises naturally from the social engineering framing: catharsis/emotional release.

If we start with the compound hypothesis that conservative movement propaganda and disinformation has driven a significant portion of the population (let's call it 20 to 40% just to have a ballpark) into a highly unpleasant state of stress and cognitive dissonance and that these people gravitate toward and reward anyone who relieves this emotional tension, either through message, affect, or language.

Consider affect for a moment. From the standpoint of someone who has spent the past few years or even decades hearing a relentless gusher of stories about welfare cheats and foreign criminals and persecution of Christians and countless other threats and outrages, a politician like Mitt Romney seems so bizarrely out of touch as to suggest collaboration or some form of mental illness.

For people in the treatment group, politicians like Trump and members of the tea party provide an enormous sense of emotional release because finally the leaders of the party are saying what the subjects see as appropriate things in an appropriate manner. For the most part this seems to be because this new crop of politicians also received the treatment.

I don't want to get too caught up in the finer distinctions between catharsis, emotional release, relief of stress, etc. What matters is that the conservative movement has spent more than a quarter century using distorted news and disinformation to cultivate a base motivated by anxiety bordering on panic and anger bordering on rage. It is easy to see why the leaders believed that having a base this motivated and hostile to the opposition would be to their advantage. It is not so easy to see why they believed they could control it indefinitely.

Friday, August 9, 2019

I have to admit I winced a little when he made the guided missile comparison

One of the things that always strikes me when looking at these fifties predictions for the future of space travel is how much Apollo scaled back those ambitions, despite costing perhaps double what people expected.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

Tesla's claims are not just unbelievable; they aren't even internally consistent

Over at Jalopnik, Aaron Gordon has an excellent rundown of the Boring Company's Las Vegas tunnel project, but the most important section focuses on another part of the Elon Musk organization. [emphasis added]

For those who haven't been following this story, Musk's claim that a fleet of Tesla robotaxis is just around the corner is a perhaps essential part of the justification of the company's stock price. The audacity was remarkable, even for him. To run an Uber-type service without human backup drivers requires complete level-5 autonomy, and that appears to be years away.

Though not quite bullshit free, compared to a standard Musk spiel, the Las Vegas project has to be grounded in reality. There are actual contracts and deliverables to consider. In other words, this is what Tesla promises when they know they'll be held accountable.

So, we’re supposed to believe Teslas will be capable of full-self driving in all conditions by next year even though, by the following year, a safety driver will be needed for a .8-mile tunnel with a dedicated right-of-way, the single simplest application of self-driving that could possibly exist.

Not only does this lend serious doubts to the Tesla robotaxi promise, but it is also a definitive step backwards from better, existing technology.

Airport people movers, close relatives to whatever the hell The Boring Company is building in Las Vegas, have been driverless for decades. Just last month, for example, I had a lovely, quick journey on Denver International Airport’s driverless people mover, which opened in 1995.

Yet here we are, in 2019, and The Boring Company says they’ll need a driver for their people-mover which moves fewer people over a shorter distance for “additional safety.”

But, hey, 1 million robotaxis on the road by next year. If you can’t believe Elon Musk, who can you believe?

For those who haven't been following this story, Musk's claim that a fleet of Tesla robotaxis is just around the corner is a perhaps essential part of the justification of the company's stock price. The audacity was remarkable, even for him. To run an Uber-type service without human backup drivers requires complete level-5 autonomy, and that appears to be years away.

Though not quite bullshit free, compared to a standard Musk spiel, the Las Vegas project has to be grounded in reality. There are actual contracts and deliverables to consider. In other words, this is what Tesla promises when they know they'll be held accountable.

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

As the consequences of the conservative movement's media strategy grows more costly...

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

How things got this bad -- part 4,675

I was digging through the archives researching an upcoming post and I came across a link from 2014. It led to a Talking Points Memo article that I had meant to write about at the time but had never gotten around to.Since then, we have learned just how much the mainstream media was covering for Roger Ailes. Ideological differences proved trivial compared to social and professional ties and an often symbiotic relationship. We have also seen how unconcerned the mainstream press (and particularly the New York Times) can be a bout a genuinely chilling attack on journalism as long as that attack is directed at someone the establishment does not like.

It was a good read in 2014, but it has gained considerable resonance since then.

From Tom Kludt:

Janet Maslin didn’t much care for Gabriel Sherman’s critical biography of Roger Ailes. In her review of “The Loudest Voice in the Room” for the New York Times on Sunday, Maslin was sympathetic to Ailes and argued that Sherman’s tome was hollow. But what Maslin didn’t note is her decades-long friendship with an Ailes employee.

Gawker’s J.K. Trotter reported Wednesday on Maslin’s close bond with Peter Boyer, the former Newsweek reporter who joined Fox News as an editor in 2012. In a statement provided to Gawker, a Times spokeswoman dismissed the idea that the relationship posed a conflict of interest.

“Janet Maslin has been friends with Peter Boyer since the 1980’s when they worked together at The Times,” the spokeswoman said. “Her review of Gabe Sherman’s book was written independent of that fact.”

Tuesday, August 6, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

Truly impressive to have turned what was a steady low-profit business for 8,000 years (driving people around for money) into a spectacular money loser with accelerating losses. https://t.co/iAcRxCPNRI— Nicole of Hell's Kitchen 🚌🚆🚇🚲🇺🇸🇫🇷 (@nicolegelinas) August 5, 2019

I can't fix racism or gun laws, but I can run a content analyses and empirically illustrate that Fox News aggressively frames immigration in terms of threat, criminality, and infestation... and you can share it if you want to help folks understand how media framing works. pic.twitter.com/j1LBuZQpBd— Dr. Danna Young🇺🇸✌🏻 (@dannagal) August 4, 2019

Yeah, that's the ticket. https://t.co/LVIEz7oR8U— Charles P. Pierce (@CharlesPPierce) August 4, 2019

Particularly in conjunction with this.https://t.co/u2jx80e21H— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 3, 2019

Forget it Jake. It's...Pundit Town.— driftglass (@Mr_Electrico) August 1, 2019

How much time do Republican presidential candidates spend discussing policy ideas that are popular with the majority of the American people? https://t.co/862d7xLyll— Osita Nwanevu (@OsitaNwanevu) August 1, 2019

This goes to the heart of the problem with Chait's education writings. His heart's in the right place and he cares deeply but his knowledge of the field is spotty at best. Among actual educators, this issue has been widely discussed for years.

An incredible scam where rich kids can buy extra time to take the SAT or ACT. How can the boards let this go on? https://t.co/F0F81esaX8— Jonathan Chait (@jonathanchait) July 31, 2019

1858 man argues telegraph makes information travel too fast:

"Ten days brings us the mails from Europe. What need is there for the scraps of news in ten minutes? How trivial and paltry is the telegraphic column? It snowed here, it rained there, one man killed, another hanged." pic.twitter.com/yz7mf7BoPL— Pessimists Archive Podcast (@PessimistsArc) August 2, 2019

Monday, August 5, 2019

Persistence of Narrative -- Netflix edition

One of the interesting things about the reaction to the recent bad news at Netflix is the way that the bulls are sticking not just with the company but with the narrative.

The claim makes no sense in terms of business, but it makes great sense in terms of story. Ads were the old way. Netflix is the disruptor. The success of the disruptor is an essential part of our modern mythology. You don't stop believing just because the evidence turns against you.

Even more central to the Netflix narrative was the role of original content. That was the competitive advantage, the secret of their success. "Secret" turned out to be something of an operative word. For years, the company managed to keep actual numbers largely out of the discourse. Recently though, the picture has started to fill in. We now know that, despite billions in production and billions more pushing these shows, originals account for only a quarter of the hours viewed and many of those shows don't exactly belong to Netflix.

"The company appears to operate in a virtuous cycle, as the larger their subscriber base grows ... the more they can spend on original content, which increases the potential target market for their service," said Jeffrey Wlodarczak, an analyst with Pivotal Research Group, in a report after its recent earnings release.

Let's start with the rather bizarre claim that Netflix will "remain a hit with consumers" because it refused to launch a second ad-supported service. Taken on its own, the reasoning is hard to follow -- a second service might not be profitable but there's no reason it would turn off members -- but it also flies in the face of recent developments in the industry. The free-with-commercials model has had a big resurgence with major players like PlutoTV and Amazon's Freedive entering the streaming space and Terrestrial Super-Stations like MeTV posting extraordinary profits.

Wlodarczak added that Netflix may remain a hit with consumers because it has continued to defy calls to launch a service with commercials, even though an ad-supported plan could be cheaper. He dubbed Netflix "an increasingly compelling unique entertainment experience on virtually any device."

The claim makes no sense in terms of business, but it makes great sense in terms of story. Ads were the old way. Netflix is the disruptor. The success of the disruptor is an essential part of our modern mythology. You don't stop believing just because the evidence turns against you.

Even more central to the Netflix narrative was the role of original content. That was the competitive advantage, the secret of their success. "Secret" turned out to be something of an operative word. For years, the company managed to keep actual numbers largely out of the discourse. Recently though, the picture has started to fill in. We now know that, despite billions in production and billions more pushing these shows, originals account for only a quarter of the hours viewed and many of those shows don't exactly belong to Netflix.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)