[This was never my area of expertise, and what little I once knew I've mostly forgotten. Since lots of our regular readers are experts on this sort of things, I welcome criticism but I hope you'll be gentle.]

I tried a little project of my own back in the early 2000s. One of these days, I'd like to revisit the topic here and talk about what I had in mind and how quixotic the whole thing was, but for now there's one aspect of it that has become particularly relevant so here's a very quick overview so I can get to the main point.

Imagine you have an agent-based simulation with a fixed number of iterations and a fixed number of runs. You randomly place the agents on a landscape with multiple dimensions and multiple optima and have them each perform gradient searches. Now we add one wrinkle. Each agent is aware of the position of at least one other agent and will move toward either the highest point in its search radius unless another searcher it is in communication with has a higher position in which case it heads toward that one.

What happens to average height when we add lines of communication to the matrix? At one extreme where each searcher is only in contact with one other, you are much more likely to have one of them find the global optima but most will be left behind. At the other extreme, if everyone is in contact with everyone, there is a far greater chance of converging on a substandard local optima. Every time I ran a set of simulations, I got the same U-shaped curve with the best results coming from a high but not too high level of communication.

It is always dangerous to extend these abstract ideas derived from artificial scenarios to the real world, but there are some fairly obvious conclusions we can draw. What if we think of the primary process in similar terms? Each voter is doing an optimization search, bringing in information on their own and trying to determine the best choice, but at the same time, they are also weighing the opinions of others performing the same search.

Given this framework, what is the optimal level of communication between voters via the polls? At what point does the frequency of polling reach a level where it makes it more likely for voters to converge on a sub-optimal choice? I'm pretty sure we've passed it.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

These seem to stand on their own.

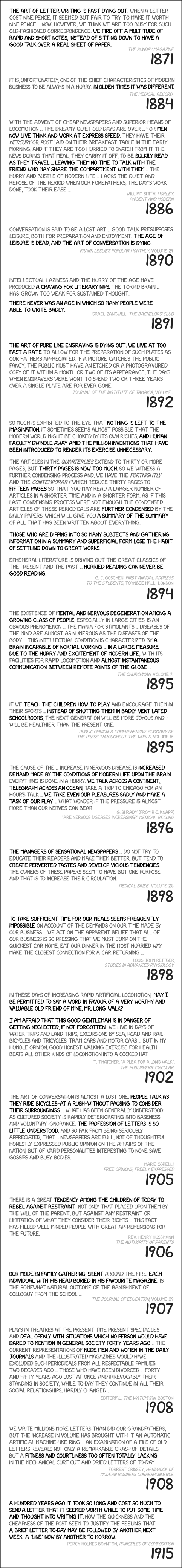

Humans love to socialize, it is a basic human need. When new technologies facilitate it, suddenly we call it an addiction. https://t.co/YuzjQJ8E4E— Pessimists Archive (@PessimistsArc) August 10, 2019

I know we've been over this one before, but I keep coming back to the traffic cop question. True level five should be able to handle a human directing traffic but it remains a tremendously challenging problem for AI.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 10, 2019

Here in Charleston it really doesn't matter when restaurants open or close because one day the entire city will be underwater, nothing will exist, and all our pain and suffering will disappear.

Eat Bubba Gump Shrimp.

Or don't. Because it's gone.https://t.co/0PLZm4Wk2s— The Post and Courier (@postandcourier) August 9, 2019

Spoiler alert: they mostly don't exist, despite Elon Musk talking about them constantly. https://t.co/LpbhwFHKPr— Timothy B. Lee (@binarybits) August 10, 2019

It still amazes me that we did any programming at at before we could look up code on Google.— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 8, 2019

Since I'm now getting "there was never any hype" revisionism in my comments, some handy (but far from exhaustive) screenshots pic.twitter.com/OGI22iJiY5— Scott Lemieux (@LemieuxLGM) August 6, 2019

Are we entirely certain he was joking? https://t.co/rXk4P94FhH— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 10, 2019

Monday, August 12, 2019

Repost, repost, repost (I want to revisit this thread)

Monday, February 4, 2019

America is a country bitterly divided into two groups – – treatment and control.

The following would sound paranoid if it hadn't been so openly discussed by the leaders of the conservative movement in real time. At the risk of slightly oversimplifying, during the flush years of the Reagan administration, these leaders came up with a multipart plan to address the challenge of maintaining power in America while pursuing policies that lacked majority support.The plan included devoting resources to high value-to-cost races such as midterms and statehouses, gerrymandering and voter suppression, dominance of and greater freedom to use campaign money, a highly disciplined carrot and stick approach to the establishment media that played shrewdly on its weaknesses and biases, and a massive social engineering experiment.

The pundit class has always had a problem with acknowledging and honestly addressing the various aspects of this plan, but it is the last element which indicates the largest blind spot. Commentators and more embarrassingly even some political scientists have pushed a string of theories that don't come close to fitting the facts with at least one requiring that West Virginia be re-assigned to the Confederacy.

All of this flailing around might be excusable if there were not an obvious explanation that almost perfectly describes the data. At least on a high level, all you need to ask yourself is who got the treatment?

Yes, there are certainly complications and complexities that need to be addressed. We need to talk about why certain people respond better. We need to look at the various channels and mechanisms beyond media including Astroturfing and the corruption of many of the leaders of the evangelical movement (particularly those espousing prosperity gospel). We need to acknowledge that this is not a clean experiment and that there are multiple levels of selection effects to contend with.

Those details, while important, are secondary. For now, the point we need to focus on is that there is a remarkably strong correspondence between conservative media reaching critical mass and an area going deep red, pro-Trump.

Unquestionably, the causal arrows run both ways here and we should approach some of the more subtle questions with caution, but the highly simplified model – – conservative propaganda and disinformation are the primary drivers of the rise of the reactionary right – – does an extraordinarily good job in explaining the last decade and the reluctance of many commentators and researchers to embrace it is itself a social phenomenon worth studying.

Tuesday, February 5, 2019

Rational actors, stag hunts and the GOP

We have hit this idea in passing a few times in the past (particularly when discussing the Ponzi threshold), but I don't believe we've ever done a post on it. While there's nothing especially radical about the idea (it shows up in discussions of risk fairly frequently), it is different enough to require a conscious shift in thinking and, under certain circumstances, it can have radically different implications.Most of the time, we tend to think of rational behavior in terms of optimizing expected values, but it is sometimes useful to think in terms of maximizing the probability of being above or below a certain threshold. Consider the somewhat overly dramatic example of a man told that he will be killed by a loan shark if he doesn't have $5000 by the end of the day. In this case, putting all of his money on a long shot at the track might well be his most rational option.

You can almost certainly think of less extreme cases where you have used the same approach, trying to figure out the best way to ensure you had at least a certain amount of money in your checking account or had set aside enough for a mortgage payment.

Often, these two ways of thinking about rational behavior are interchangeable, but not always. Our degenerate gambler is one example, and I've previously argued that overvalued companies like Uber or Netflix are another, the one I've been thinking about a lot recently is the Republican Party and its relationship with Trump.

Without going into too much detail (these are subjects for future posts), one of the three or four major components of the conservative movement's strategy was a social engineering experiment designed to create a loyal and highly motivated base. The initiative worked fairly well for a while, but with the rise of the tea party and then the Trump wing, the leaders of the movement lost control of the faction they had created. (Have we done a post positing the innate instability of the Straussian model and other systems based on disinformation? I've lost track.)

In 2016, the Republican Party had put itself in the strange position of having what should have been their most reliable core voters fanatically loyal to someone completely indifferent to the interests of the party, someone who was capable of and temperamentally inclined to bringing the whole damn building down it forced out. Since then, I would argue that the best way of understanding the choices of those Republicans not deep in the cult of personality is to think of them optimizing against a shifting threshold.

Trump's 2016 victory was only possible because a number of things lined up exactly right, many of which were dependent on the complacency of Democratic voters, the press, and the political establishment. Repeating this victory in 2020 without the advantage of surprise would require Trump to have exceeded expectations and started to win over non-supporters. Even early in 2017, this seemed unlikely, so most establishment Republicans started optimizing for a soft landing, hoping to hold the house in 2018 while minimizing the damage from 2020. They did everything they could to delay investigations into Trump scandals, attempted to surround him with "grown-ups," and presented a unified front while taking advantage of what was likely to be there last time at the trough for a while.

Even shortly before the midterms, it became apparent that a soft landing was unlikely and the threshold shifted to hard landing. The idea of expanding on the Trump base was largely abandoned as were any attempts to restrain the president. The objective now was to maintain enough of a foundation to rebuild up on after things collapsed.

With recent events, particularly the shutdown, the threshold shifted again to party viability. Arguably the primary stated objective of the conservative movement has always been finding a way to maintain control in a democracy while promoting unpopular positions. This inevitably results in running on thinner and thinner margins. The current configuration of the movement has to make every vote count. This gives any significant faction of the base the power to cost the party any or all elections for the foreseeable future.

It is not at all clear how the GOP would fill the hole left by a defection of the anti-immigrant wing or of those voters who are personally committed to Trump regardless of policy. Having these two groups suddenly and unexpectedly at odds with each other (they had long appeared inseparable) is tremendously worrisome for Republicans, but even a unified base can't compensate for sufficiently unpopular policies. Another shutdown or the declaration of a state of emergency both appear to have the potential to damage the party's prospects not just in 2020 but in the following midterms and perhaps even 2024.

So far, the changes in optimal strategy associated with the shifting thresholds have been fairly subtle, but if the threshold drops below party viability, things get very different very quickly. We could and probably should frame this in terms of stag hunts and Nash equilibria but you don't need to know anything about game theory to understand that when a substantial number of people in and around the Republican Party establishment stop acting under the assumption that there will continue to be a Republican Party, then almost every other assumption we make about the way the party functions goes out the window.

Just to be clear, I'm not making predictions about what the chaos will look like; I'm saying you can't make predictions about it. A year from now we are likely to be in completely uncharted water and any pundit or analyst who makes confident data-based pronouncements about what will or won't happen is likely to lose a great deal of credibility.

Monday, February 11, 2019

Catharsis

Picking up from our previous post about approaching the rise of the Trump voter in terms of a social engineering experiment, one of the best indicators of epicyclic thinking is that each adjustment helps explain only one isolated aspect of the situation. In contrast, when introducing a good framework or mental model, most of what we see should suddenly make more sense. This applies not only to what happens but to how it happens.With that in mind, let's talk about something that has been largely absent from the various think pieces on the subject but which has great explanatory power and which rises naturally from the social engineering framing: catharsis/emotional release.

If we start with the compound hypothesis that conservative movement propaganda and disinformation has driven a significant portion of the population (let's call it 20 to 40% just to have a ballpark) into a highly unpleasant state of stress and cognitive dissonance and that these people gravitate toward and reward anyone who relieves this emotional tension, either through message, affect, or language.

Consider affect for a moment. From the standpoint of someone who has spent the past few years or even decades hearing a relentless gusher of stories about welfare cheats and foreign criminals and persecution of Christians and countless other threats and outrages, a politician like Mitt Romney seems so bizarrely out of touch as to suggest collaboration or some form of mental illness.

For people in the treatment group, politicians like Trump and members of the tea party provide an enormous sense of emotional release because finally the leaders of the party are saying what the subjects see as appropriate things in an appropriate manner. For the most part this seems to be because this new crop of politicians also received the treatment.

I don't want to get too caught up in the finer distinctions between catharsis, emotional release, relief of stress, etc. What matters is that the conservative movement has spent more than a quarter century using distorted news and disinformation to cultivate a base motivated by anxiety bordering on panic and anger bordering on rage. It is easy to see why the leaders believed that having a base this motivated and hostile to the opposition would be to their advantage. It is not so easy to see why they believed they could control it indefinitely.

Friday, August 9, 2019

I have to admit I winced a little when he made the guided missile comparison

One of the things that always strikes me when looking at these fifties predictions for the future of space travel is how much Apollo scaled back those ambitions, despite costing perhaps double what people expected.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

Tesla's claims are not just unbelievable; they aren't even internally consistent

Over at Jalopnik, Aaron Gordon has an excellent rundown of the Boring Company's Las Vegas tunnel project, but the most important section focuses on another part of the Elon Musk organization. [emphasis added]

For those who haven't been following this story, Musk's claim that a fleet of Tesla robotaxis is just around the corner is a perhaps essential part of the justification of the company's stock price. The audacity was remarkable, even for him. To run an Uber-type service without human backup drivers requires complete level-5 autonomy, and that appears to be years away.

Though not quite bullshit free, compared to a standard Musk spiel, the Las Vegas project has to be grounded in reality. There are actual contracts and deliverables to consider. In other words, this is what Tesla promises when they know they'll be held accountable.

So, we’re supposed to believe Teslas will be capable of full-self driving in all conditions by next year even though, by the following year, a safety driver will be needed for a .8-mile tunnel with a dedicated right-of-way, the single simplest application of self-driving that could possibly exist.

Not only does this lend serious doubts to the Tesla robotaxi promise, but it is also a definitive step backwards from better, existing technology.

Airport people movers, close relatives to whatever the hell The Boring Company is building in Las Vegas, have been driverless for decades. Just last month, for example, I had a lovely, quick journey on Denver International Airport’s driverless people mover, which opened in 1995.

Yet here we are, in 2019, and The Boring Company says they’ll need a driver for their people-mover which moves fewer people over a shorter distance for “additional safety.”

But, hey, 1 million robotaxis on the road by next year. If you can’t believe Elon Musk, who can you believe?

For those who haven't been following this story, Musk's claim that a fleet of Tesla robotaxis is just around the corner is a perhaps essential part of the justification of the company's stock price. The audacity was remarkable, even for him. To run an Uber-type service without human backup drivers requires complete level-5 autonomy, and that appears to be years away.

Though not quite bullshit free, compared to a standard Musk spiel, the Las Vegas project has to be grounded in reality. There are actual contracts and deliverables to consider. In other words, this is what Tesla promises when they know they'll be held accountable.

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

As the consequences of the conservative movement's media strategy grows more costly...

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

How things got this bad -- part 4,675

I was digging through the archives researching an upcoming post and I came across a link from 2014. It led to a Talking Points Memo article that I had meant to write about at the time but had never gotten around to.Since then, we have learned just how much the mainstream media was covering for Roger Ailes. Ideological differences proved trivial compared to social and professional ties and an often symbiotic relationship. We have also seen how unconcerned the mainstream press (and particularly the New York Times) can be a bout a genuinely chilling attack on journalism as long as that attack is directed at someone the establishment does not like.

It was a good read in 2014, but it has gained considerable resonance since then.

From Tom Kludt:

Janet Maslin didn’t much care for Gabriel Sherman’s critical biography of Roger Ailes. In her review of “The Loudest Voice in the Room” for the New York Times on Sunday, Maslin was sympathetic to Ailes and argued that Sherman’s tome was hollow. But what Maslin didn’t note is her decades-long friendship with an Ailes employee.

Gawker’s J.K. Trotter reported Wednesday on Maslin’s close bond with Peter Boyer, the former Newsweek reporter who joined Fox News as an editor in 2012. In a statement provided to Gawker, a Times spokeswoman dismissed the idea that the relationship posed a conflict of interest.

“Janet Maslin has been friends with Peter Boyer since the 1980’s when they worked together at The Times,” the spokeswoman said. “Her review of Gabe Sherman’s book was written independent of that fact.”

Tuesday, August 6, 2019

Tuesday Tweets

Truly impressive to have turned what was a steady low-profit business for 8,000 years (driving people around for money) into a spectacular money loser with accelerating losses. https://t.co/iAcRxCPNRI— Nicole of Hell's Kitchen 🚌🚆🚇🚲🇺🇸🇫🇷 (@nicolegelinas) August 5, 2019

I can't fix racism or gun laws, but I can run a content analyses and empirically illustrate that Fox News aggressively frames immigration in terms of threat, criminality, and infestation... and you can share it if you want to help folks understand how media framing works. pic.twitter.com/j1LBuZQpBd— Dr. Danna Young🇺🇸✌🏻 (@dannagal) August 4, 2019

Yeah, that's the ticket. https://t.co/LVIEz7oR8U— Charles P. Pierce (@CharlesPPierce) August 4, 2019

Particularly in conjunction with this.https://t.co/u2jx80e21H— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) August 3, 2019

Forget it Jake. It's...Pundit Town.— driftglass (@Mr_Electrico) August 1, 2019

How much time do Republican presidential candidates spend discussing policy ideas that are popular with the majority of the American people? https://t.co/862d7xLyll— Osita Nwanevu (@OsitaNwanevu) August 1, 2019

This goes to the heart of the problem with Chait's education writings. His heart's in the right place and he cares deeply but his knowledge of the field is spotty at best. Among actual educators, this issue has been widely discussed for years.

An incredible scam where rich kids can buy extra time to take the SAT or ACT. How can the boards let this go on? https://t.co/F0F81esaX8— Jonathan Chait (@jonathanchait) July 31, 2019

1858 man argues telegraph makes information travel too fast:

"Ten days brings us the mails from Europe. What need is there for the scraps of news in ten minutes? How trivial and paltry is the telegraphic column? It snowed here, it rained there, one man killed, another hanged." pic.twitter.com/yz7mf7BoPL— Pessimists Archive Podcast (@PessimistsArc) August 2, 2019

Monday, August 5, 2019

Persistence of Narrative -- Netflix edition

One of the interesting things about the reaction to the recent bad news at Netflix is the way that the bulls are sticking not just with the company but with the narrative.

The claim makes no sense in terms of business, but it makes great sense in terms of story. Ads were the old way. Netflix is the disruptor. The success of the disruptor is an essential part of our modern mythology. You don't stop believing just because the evidence turns against you.

Even more central to the Netflix narrative was the role of original content. That was the competitive advantage, the secret of their success. "Secret" turned out to be something of an operative word. For years, the company managed to keep actual numbers largely out of the discourse. Recently though, the picture has started to fill in. We now know that, despite billions in production and billions more pushing these shows, originals account for only a quarter of the hours viewed and many of those shows don't exactly belong to Netflix.

"The company appears to operate in a virtuous cycle, as the larger their subscriber base grows ... the more they can spend on original content, which increases the potential target market for their service," said Jeffrey Wlodarczak, an analyst with Pivotal Research Group, in a report after its recent earnings release.

Let's start with the rather bizarre claim that Netflix will "remain a hit with consumers" because it refused to launch a second ad-supported service. Taken on its own, the reasoning is hard to follow -- a second service might not be profitable but there's no reason it would turn off members -- but it also flies in the face of recent developments in the industry. The free-with-commercials model has had a big resurgence with major players like PlutoTV and Amazon's Freedive entering the streaming space and Terrestrial Super-Stations like MeTV posting extraordinary profits.

Wlodarczak added that Netflix may remain a hit with consumers because it has continued to defy calls to launch a service with commercials, even though an ad-supported plan could be cheaper. He dubbed Netflix "an increasingly compelling unique entertainment experience on virtually any device."

The claim makes no sense in terms of business, but it makes great sense in terms of story. Ads were the old way. Netflix is the disruptor. The success of the disruptor is an essential part of our modern mythology. You don't stop believing just because the evidence turns against you.

Even more central to the Netflix narrative was the role of original content. That was the competitive advantage, the secret of their success. "Secret" turned out to be something of an operative word. For years, the company managed to keep actual numbers largely out of the discourse. Recently though, the picture has started to fill in. We now know that, despite billions in production and billions more pushing these shows, originals account for only a quarter of the hours viewed and many of those shows don't exactly belong to Netflix.

Friday, August 2, 2019

11 songs that more people should know -- Special Guest Blogger

[I had to delay today's post, so I asked an old friend (and pop culture maven) to suggest a few undeservedly obscure songs to kick off the weekend. Not actually what I meant by a "few" but I'm not complaining.]

Hello! I'm Brian Phillips and here are 11 songs that you may not know, but really should. If you like an eclectic mix of music, take a listen to my show, The Electro-Phonic Sound of Brian Phillips at rockinradio.com

1. The Crew was a positively dismal show, but fortunately, the producers had the good sense to hire Wendy Coleman and Lisa Melvoin, late of Prince and the Revolution, to do the very catchy theme. If you continue to watch...you have been warned.

2. "Treemonisha" was a triumph for the composer Scott Joplin, albeit posthumously. Sadly his opera, was never fully staged in his lifetime, but when "The Sting", which made extensive use of his music, it triggered a full-blown revival and the opera was finally staged in the 1970's. This is the finale and the oft-used Joplin quote applies here: "One should never play Ragtime fast". This is the "Real Slow Drag"

3. From Houston, TX, it's Lee Alexander! This was recorded in 2006. This may be his only album.

4. Tribe was a band out of Boston and they recorded two albums before splitting up. They never got very popular outside of their hometown, even with the backing of Warner Brothers Records. There aren't as many great Rock songs in waltz time, but this is a good one!

5. The Blue Ribbon Syncopators, a band out of Buffalo, NY who made six known recordings. Banjo is prominent here and, like the tuba, was mostly gone from Jazz by the 1930's

6. This is quite a lot of noise from this NY band, led by the chief songwriter, Joe Docko. Docko was 16 and one can only wonder what his music career would have been, if the Mystic Tide had any significant success. The highlight of this song are the two vocal lines. Docko destroyed all of his remaining Mystic Tide records, so what is out in the wild is all that is left.

7. Looking for the Beagles? For a time, some people were. This was a cartoon by Total Television, the same folks that made Underdog. It wasn't a hit and it was thought to be lost until recently. Surprisingly there was a soundtrack LP from the show, and it has become a collector's item, not only because of its rarity, but the music is quite good.

8. Joe Maphis was one of those fellows who went to the talent store and stayed longer than most. Don't believe me? Take a look at this and watch what he does at 2:00:

9. This is Kenneth "Thumbs" Carllile. You'll see why they called him that when you watch this. He was a sideman with Roger Miller for a number of years and released several albums under his own name.

10. Oscar Coleman, aka Bo Dudley, is the leader of this session, but what makes this song great is the incendiary pedal steel guitar of Freddie Roulette, who was a sideman to Earl Hooker and Johnny "Big Moose" Walker, and he also recorded as a leader later in his career.

11. Have a good weekend everyone! I am not quite sure why this wasn't a hit. Here are the Loved Ones from California.

Hello! I'm Brian Phillips and here are 11 songs that you may not know, but really should. If you like an eclectic mix of music, take a listen to my show, The Electro-Phonic Sound of Brian Phillips at rockinradio.com

1. The Crew was a positively dismal show, but fortunately, the producers had the good sense to hire Wendy Coleman and Lisa Melvoin, late of Prince and the Revolution, to do the very catchy theme. If you continue to watch...you have been warned.

2. "Treemonisha" was a triumph for the composer Scott Joplin, albeit posthumously. Sadly his opera, was never fully staged in his lifetime, but when "The Sting", which made extensive use of his music, it triggered a full-blown revival and the opera was finally staged in the 1970's. This is the finale and the oft-used Joplin quote applies here: "One should never play Ragtime fast". This is the "Real Slow Drag"

3. From Houston, TX, it's Lee Alexander! This was recorded in 2006. This may be his only album.

4. Tribe was a band out of Boston and they recorded two albums before splitting up. They never got very popular outside of their hometown, even with the backing of Warner Brothers Records. There aren't as many great Rock songs in waltz time, but this is a good one!

5. The Blue Ribbon Syncopators, a band out of Buffalo, NY who made six known recordings. Banjo is prominent here and, like the tuba, was mostly gone from Jazz by the 1930's

6. This is quite a lot of noise from this NY band, led by the chief songwriter, Joe Docko. Docko was 16 and one can only wonder what his music career would have been, if the Mystic Tide had any significant success. The highlight of this song are the two vocal lines. Docko destroyed all of his remaining Mystic Tide records, so what is out in the wild is all that is left.

7. Looking for the Beagles? For a time, some people were. This was a cartoon by Total Television, the same folks that made Underdog. It wasn't a hit and it was thought to be lost until recently. Surprisingly there was a soundtrack LP from the show, and it has become a collector's item, not only because of its rarity, but the music is quite good.

8. Joe Maphis was one of those fellows who went to the talent store and stayed longer than most. Don't believe me? Take a look at this and watch what he does at 2:00:

9. This is Kenneth "Thumbs" Carllile. You'll see why they called him that when you watch this. He was a sideman with Roger Miller for a number of years and released several albums under his own name.

10. Oscar Coleman, aka Bo Dudley, is the leader of this session, but what makes this song great is the incendiary pedal steel guitar of Freddie Roulette, who was a sideman to Earl Hooker and Johnny "Big Moose" Walker, and he also recorded as a leader later in his career.

11. Have a good weekend everyone! I am not quite sure why this wasn't a hit. Here are the Loved Ones from California.

Thursday, August 1, 2019

What Nate silver has in common with Bob Dylan, Tom Wolfe, and Pauline Kael.

I don't remember if I ever got around to it, but for years I've been meaning to write an Andrew Gelman style class post on people whose work is great but whose imitators drag down the field.

I go back and forth on Bob Dylan here. There is no counting how many coffee house hacks have convinced themselves that the obscure lyrics they are croaking out are the next Tangled Up In Blue. On the other hand, a lot of brilliant artists have done some of their best work inspired by Dylan.

With Tom Wolfe and Pauline Kael, however, the divide in quality between the originals and the imitators is much more sharp. For more than 50 years now, we have suffered through journalists and critics who have annoyingly affected the tics and mannerisms of both writers, while having none of the talent or insight and being completely unwilling to put in the hard work of research and revision that made Wolfe and Kael so formidable.

I don't want to oversell Nate Silver at this point (he's no Bob Dylan) but he deserves great credit for his Innovations in the way we cover politics. He saw the fundamental problem with remarkable clarity and understood the appropriate level of complexity needed for a solution. As a statistician, he has considerable limitations. When he strays too far from his areas of expertise such as when he writes about climate models, the dunning-kruger effect has a tendency to come down hard, but he does have a natural talent and an all too rare capacity to learn from his mistakes.

His success unfortunately has inspired a wave of data journalists who are more often than not terrible at their jobs. It turns out that being enamored with data and yet being bad statistics is often worse than ignoring data entirely.

I go back and forth on Bob Dylan here. There is no counting how many coffee house hacks have convinced themselves that the obscure lyrics they are croaking out are the next Tangled Up In Blue. On the other hand, a lot of brilliant artists have done some of their best work inspired by Dylan.

With Tom Wolfe and Pauline Kael, however, the divide in quality between the originals and the imitators is much more sharp. For more than 50 years now, we have suffered through journalists and critics who have annoyingly affected the tics and mannerisms of both writers, while having none of the talent or insight and being completely unwilling to put in the hard work of research and revision that made Wolfe and Kael so formidable.

I don't want to oversell Nate Silver at this point (he's no Bob Dylan) but he deserves great credit for his Innovations in the way we cover politics. He saw the fundamental problem with remarkable clarity and understood the appropriate level of complexity needed for a solution. As a statistician, he has considerable limitations. When he strays too far from his areas of expertise such as when he writes about climate models, the dunning-kruger effect has a tendency to come down hard, but he does have a natural talent and an all too rare capacity to learn from his mistakes.

His success unfortunately has inspired a wave of data journalists who are more often than not terrible at their jobs. It turns out that being enamored with data and yet being bad statistics is often worse than ignoring data entirely.

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Any conversation about electability has got to start with the fact that a white male has not won the popular vote since 2004.

The electoral discussion among pundits and data journalists has been taking some especially silly turns of late and before the bullshit accumulates to the same dangerous level it did in 2016, we need to step back and address the bad definitions, absurd assumptions, and muddled thinking before it gets too deep.

We should probably start with the idea electability. While we can argue about the exact definition, it should not mean likely to be elected and it absolutely cannot mean will be elected.

Any productive definition of electability has got to be based on the notion of having reasonable prospect of winning. With this in mind, it is ridiculous to argue that Hillary Clinton was not electable. Lots of things had to break Trump's way for him to win the election and, while we can never say for certain what repeated runs of the simulation would show, there is no way to claim that we would have gotten the same outcome the vast majority of the time.

This leads us to a related dangerous and embarrassing trend, the unmooring of votes and outcomes. This is part of a larger genre of bad data journalism that tries to argue that relationships which are strongly correlated and even causal are unrelated because they are not deterministic and/or linear. In this world, profit or even potential profit is not relevant when discussing a startup's success. Diet and exercise have no effect on weight loss. With a little digging you can undoubtedly come up with numerous other examples.

The person who wins the popular vote may not win the electoral college, but unless you have a remarkably strong argument to the contrary, that is the way that smart money should bet.

We should probably start with the idea electability. While we can argue about the exact definition, it should not mean likely to be elected and it absolutely cannot mean will be elected.

Any productive definition of electability has got to be based on the notion of having reasonable prospect of winning. With this in mind, it is ridiculous to argue that Hillary Clinton was not electable. Lots of things had to break Trump's way for him to win the election and, while we can never say for certain what repeated runs of the simulation would show, there is no way to claim that we would have gotten the same outcome the vast majority of the time.

This leads us to a related dangerous and embarrassing trend, the unmooring of votes and outcomes. This is part of a larger genre of bad data journalism that tries to argue that relationships which are strongly correlated and even causal are unrelated because they are not deterministic and/or linear. In this world, profit or even potential profit is not relevant when discussing a startup's success. Diet and exercise have no effect on weight loss. With a little digging you can undoubtedly come up with numerous other examples.

The person who wins the popular vote may not win the electoral college, but unless you have a remarkably strong argument to the contrary, that is the way that smart money should bet.

Tuesday, July 30, 2019

Tuesday Tweets -- “rapid unplanned disassembly“ edition

The hyperloop achieved an impressive top speed shortly before “rapid unplanned disassembly“. You could get the same outcome much more cheaply by falling off of a tall building. @TUM_Hyperloop https://t.co/tjE9tAxm0N— Jarrett Walker (@humantransit) July 23, 2019

“Rapid unplanned disassembly“ is very likely to cause a loss of cabin pressure.@alon_levy @trnsprtst— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) July 24, 2019

Nice example of how mobile carriers are using and selling location data, which had gotten less attention than "big tech" https://t.co/EBoobJj7vb— Dean Eckles (@deaneckles) July 19, 2019

I think Lee is underplaying the role that the huge, broad-based spikes in the late 19th Century and post-war era were in forming the idea of the exponential progress curve (and how resilient the belief has been in the face of conflicting data).

It's interesting to imagine a world where humanity never invented the transistor and therefore never had a digital revolution. In that world, the obvious interpretation of economic history would be that the discovery of fossil fuels gave humanity a one-time growth spurt.— Timothy B. Lee (@binarybits) July 20, 2019

Key finding from a new @NavigatorSurvey analysis—over several months responses were collected for voters who approve of Trump on economy but NOT overall. What do they say for 2020?

.....“handling of economy” is not their driving issue

(full report: https://t.co/G1rqEdt8Xv) https://t.co/VOCHeLdwnt— Will Jordan (@williamjordann) July 19, 2019

We've been seeing the same thing in a number of supposedly red States. Ideologically they are moving to the center, perhaps even the left, on many ideological issues while becoming more Republican at the same time https://t.co/rt67z1gO0i— Mark Palko (@MarkPalko1) July 26, 2019

Not that you should expect better from one of those "Despite Thing, Voters in Trump Country Still Love Trump!" articles, but this polling showing him down 2 in Obama-Trump counties would be quite *bad* for Trump. He won Macomb County by 12 points in 2016. https://t.co/TePjzoDeJ1 pic.twitter.com/9T9ydanMeA— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) July 22, 2019

Thread by former @WSJ journalist who is fed up with what she saw this week during and after the Mueller testimony. https://t.co/PzRP6iYivK— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) July 26, 2019

Monday, July 29, 2019

Taking on the votes-don't-matter meme -- the EC doesn't always follow the popular vote, but that's the way the smart money should bet

And once again we are in the silly season.

First off, a quick disclaimer: You can never reasonably dismiss an incumbent president's chances of being reelected. No matter how poor the prospects look, there are always plausible paths to victory. Not taking Trump seriously would be irresponsible, but much of what we're hearing from the other extreme are just as foolish possibly more dangerous (the combination of defeatism, panic and bad reasoning seldom works out well).

Popular variations on the all-is-lost theme include:

"Trump is unstoppable unless the Democrats move to the right/move to the left/embrace my pet issue."

"Trump is actually pursuing a cunning plan that will insure victory."

"The popular vote doesn't matter. The electoral college went the wrong way two out of the last five elections."

Let's take that last one. The EC is a bad system that should have been scrapped long ago, but at least from a historical perspective, how likely are these undemocratic outcomes?

For starters, we need to be very careful with our terms. There is a subtle but absolutely fundamental distinction to be made between winning the presidency despite losing the popular vote and winning the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote. In 2016, there is no question that the popular vote went one way and the Electoral College went another. In 2000, however, the picture is much murkier.

When we talk about a split between the popular vote and the Electoral College we mean that, given a reasonably accurate count, the all-or-nothing allotment of votes and the minimum delegate rule for small states will cause the Electoral College totals to go in a different direction that the popular vote.

There is always a certain amount of fuzziness when dealing with ballots. There might be a very slight chance that Al Gore did not win the popular vote. There is a very good chance that he did win the electoral college. Once again, I want to be very clear on this point. I'm not talking about who was awarded the delegates. I'm talking about who would have gotten them had there been a properly conducted counting of the votes in Florida.

We've seen a recent wave of data journalist making bad distributional arguments about the implications of the Electoral College. Most of these arguments use Al Gore as an example despite the fact he does not at all illustrate their point, since who won Florida (and therefore the EC) is very much a disputed point).

If you remove Gore as an example, you have to go all the way back to 1888 to find another. This does not mean that this won't happen again for another hundred plus years. It does not mean that we don't need to worry about this in 2020. It does not even mean that a split between popular and electoral votes isn't The New Normal. What it does mean is that historically there is an extremely high correlation between winning the popular vote and winning the Electoral College.

Just for the record, the undermining of democracy by the conservative movement, particularly through voter suppression and under-representation, is perhaps my number one issue, even more than climate change and income inequality. I am very worried about gerrymandering and voter ID laws and somewhat concerned about the Senate, but the Electoral College, while not defensible, is way down on my list.

First off, a quick disclaimer: You can never reasonably dismiss an incumbent president's chances of being reelected. No matter how poor the prospects look, there are always plausible paths to victory. Not taking Trump seriously would be irresponsible, but much of what we're hearing from the other extreme are just as foolish possibly more dangerous (the combination of defeatism, panic and bad reasoning seldom works out well).

Popular variations on the all-is-lost theme include:

"Trump is unstoppable unless the Democrats move to the right/move to the left/embrace my pet issue."

"Trump is actually pursuing a cunning plan that will insure victory."

"The popular vote doesn't matter. The electoral college went the wrong way two out of the last five elections."

Let's take that last one. The EC is a bad system that should have been scrapped long ago, but at least from a historical perspective, how likely are these undemocratic outcomes?

For starters, we need to be very careful with our terms. There is a subtle but absolutely fundamental distinction to be made between winning the presidency despite losing the popular vote and winning the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote. In 2016, there is no question that the popular vote went one way and the Electoral College went another. In 2000, however, the picture is much murkier.

When we talk about a split between the popular vote and the Electoral College we mean that, given a reasonably accurate count, the all-or-nothing allotment of votes and the minimum delegate rule for small states will cause the Electoral College totals to go in a different direction that the popular vote.

There is always a certain amount of fuzziness when dealing with ballots. There might be a very slight chance that Al Gore did not win the popular vote. There is a very good chance that he did win the electoral college. Once again, I want to be very clear on this point. I'm not talking about who was awarded the delegates. I'm talking about who would have gotten them had there been a properly conducted counting of the votes in Florida.

We've seen a recent wave of data journalist making bad distributional arguments about the implications of the Electoral College. Most of these arguments use Al Gore as an example despite the fact he does not at all illustrate their point, since who won Florida (and therefore the EC) is very much a disputed point).

If you remove Gore as an example, you have to go all the way back to 1888 to find another. This does not mean that this won't happen again for another hundred plus years. It does not mean that we don't need to worry about this in 2020. It does not even mean that a split between popular and electoral votes isn't The New Normal. What it does mean is that historically there is an extremely high correlation between winning the popular vote and winning the Electoral College.

Just for the record, the undermining of democracy by the conservative movement, particularly through voter suppression and under-representation, is perhaps my number one issue, even more than climate change and income inequality. I am very worried about gerrymandering and voter ID laws and somewhat concerned about the Senate, but the Electoral College, while not defensible, is way down on my list.

Friday, July 26, 2019

Family Friendly?

This is Joseph.

This tweet makes an excellent point:

The context was the cost of summer camps when you have two working parents, without anywhere near enough holidays to cover the summer. This has to be one of the odd contradictions of modern thinking; I first noticed in in Ayn Rand's book "Atlas Shrugged" where she glossed over the role of children in a hyper-capitalist society. While not everyone is a fan of Ayn Rand, it was an early sign of a fault point in the individualist culture we have created.

The problem is that we can't really decide on two things. One, is the basic unit of humanity individuals or families? This isn't meant to be exclusionary, but simply to point out that humanity, as a project, requires new humans so if there is a commitment to the species they have to come from somewhere. I don't want to say how these come together -- family is a very diverse entity -- but they are real mechanisms for child rearing.

Two, is the social contract that Western Democracies have created is about previous generations being transferred wealth in their old age from upcoming generations. This works best when there is a continuing flow of upcoming generations and that requires some investment in the future as well.

I am not sure about the solutions, but I am pretty sure that the solution set does not include seeing children as expensive consumer goods.

This tweet makes an excellent point:

The context was the cost of summer camps when you have two working parents, without anywhere near enough holidays to cover the summer. This has to be one of the odd contradictions of modern thinking; I first noticed in in Ayn Rand's book "Atlas Shrugged" where she glossed over the role of children in a hyper-capitalist society. While not everyone is a fan of Ayn Rand, it was an early sign of a fault point in the individualist culture we have created.

The problem is that we can't really decide on two things. One, is the basic unit of humanity individuals or families? This isn't meant to be exclusionary, but simply to point out that humanity, as a project, requires new humans so if there is a commitment to the species they have to come from somewhere. I don't want to say how these come together -- family is a very diverse entity -- but they are real mechanisms for child rearing.

Two, is the social contract that Western Democracies have created is about previous generations being transferred wealth in their old age from upcoming generations. This works best when there is a continuing flow of upcoming generations and that requires some investment in the future as well.

I am not sure about the solutions, but I am pretty sure that the solution set does not include seeing children as expensive consumer goods.

Wonder when they stopped running Thunderbirds reruns in South Africa.

Listening to this, I can't help but try and reconstruct the conversations he had with the actual engineers who tried to explain these ideas to him. He gets most of the phrases right but there's no indication he understands the challenges involved in what he's talking about.

Personally, I want to see him add one of these pilot slides.

Personally, I want to see him add one of these pilot slides.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)