Repost

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Tuesday, January 1, 2019

Monday, December 31, 2018

Friday, December 28, 2018

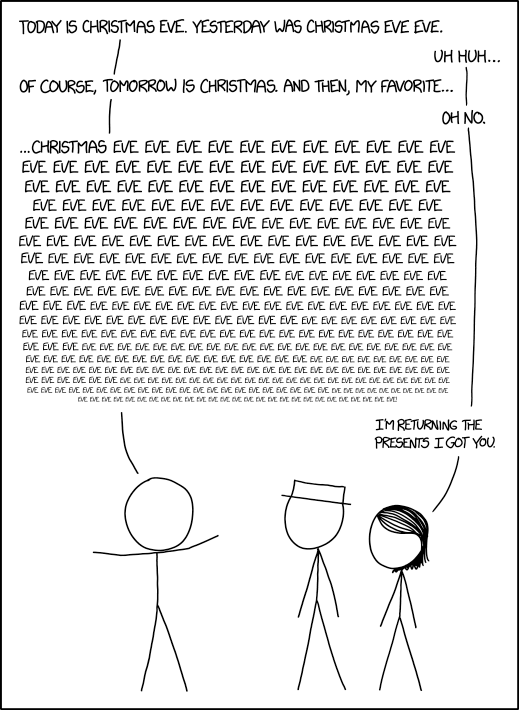

Stop me if you've heard this one.

Here's a technology story for you. Imagine you're a leading device manufacturer for a new media platform. You decide to produce original content to promote your product but you end up cancelling the project, not because the show didn't catch on but because it was so popular that you couldn't make you devices fast enough..

From Wikipedia:

I believe the following clips are from the follow-up, Your Show of Shows. You may notice how easily poor Howard Morris is tossed around. Caesar was known for being exceptional strong and while his former writers and staff held him in great regard, they also talked about him being dangerous when angry. Mel Brooks still talks about Caesar dangling him out of a window after an argument.

From Wikipedia:

[Sid] Caesar's television career began with an appearance on Milton Berle's Texaco Star Theater in the fall of 1948. In early 1949, Caesar and Liebman met with Pat Weaver, vice president of television at NBC, which led to Caesar's first series, Admiral Broadway Revue with Imogene Coca. The Friday show was simultaneously broadcast on NBC and the DuMont network, and was an immediate success. However, its sponsor, Admiral, an appliance company, could not keep up with the demand for its new television sets, so the show was cancelled after 26 weeks—ironically, on account of its runaway success.

I believe the following clips are from the follow-up, Your Show of Shows. You may notice how easily poor Howard Morris is tossed around. Caesar was known for being exceptional strong and while his former writers and staff held him in great regard, they also talked about him being dangerous when angry. Mel Brooks still talks about Caesar dangling him out of a window after an argument.

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Of all the strange turns in the story of the Elon Musk Boring company debut, this may be the funniest and the saddest.

From the Chicago Sun Times

There is a memorable anecdote in Cialdini's Influence. In the chapter on commitment, consistency, and cognitive dissonance, as memory serves, he describes seeing a mathematics professor completely dismantle a guru pitching a TM course only to see a number of people sign up anyway. When Cialdini asked some of them if they found the mathematician' s arguments, they said it was the opposite. They were starting to have doubts and wanted to make a decision before they changed their minds.

That always struck me as a little on the nose. Cialdini always builds his case with extensive evidence presented along multiple lines of attack – – sound theory with reasonable evolutionary support, controlled experiments, observational data, historical records, successful established business practices, and relevant news stories – – so an unconvincingly apt personal anecdote doesn't undercut the bigger picture.

(Much of my antipathy toward Freakonomics comes from the fact I picked it up expecting the same standard of proof.Instead, the authors seemed to treat their assertions as unquestionably true.)

After reading this, however, I'm less inclined to think that Cialdini gilded the lily. The main difference is the considerably lower level of self-awareness from the elected officials.

To be blunt, there is no rational way to come away from Musk's tunnel debut more enthusiastic about the project. There was no good news there.

1. The reviews were brutal.

2. The new proposal is slower with much lower capacity than what was promised.

3. After two years of promises, the company appears to have made no technological advances at all. No progress in tunneling techniques. Seemingly no work at all on the rest of the system. Nothing.

We have reached that point in the Musk narrative where what should cause doubt only adds to the faith of the faithful.

After a bumpy, but exhilarating California test ride, a delegation of city officials returned home Wednesday more convinced than ever that Elon Musk’s plan to build a “Tesla-in-a-tunnel” high-speed transit system between downtown and O’Hare Airport would be “transformational for Chicago,” as one said.

Deputy Mayor Bob Rivkin, who led the Chicago delegation, said he wasn’t scared when the TeslaX he was riding in descended into the tunnel, and he didn’t suffer from motion sickness after the choppy, 45-mile-an-hour ride.

That’s less than half the speed that the visionary billionaire of Tesla and SpaceX fame has promised for the $25, 12-minute ride from downtown’s Block 37 to O’Hare Airport aboard an electric vehicle seating sixteen passengers.

“The tunnel is well-lit. You can see the turns in front of you,” Rivkin said. ” … You just get a sense of the simplicity of the whole thing. It’s a tunnel with a Tesla in it.”

There is a memorable anecdote in Cialdini's Influence. In the chapter on commitment, consistency, and cognitive dissonance, as memory serves, he describes seeing a mathematics professor completely dismantle a guru pitching a TM course only to see a number of people sign up anyway. When Cialdini asked some of them if they found the mathematician' s arguments, they said it was the opposite. They were starting to have doubts and wanted to make a decision before they changed their minds.

That always struck me as a little on the nose. Cialdini always builds his case with extensive evidence presented along multiple lines of attack – – sound theory with reasonable evolutionary support, controlled experiments, observational data, historical records, successful established business practices, and relevant news stories – – so an unconvincingly apt personal anecdote doesn't undercut the bigger picture.

(Much of my antipathy toward Freakonomics comes from the fact I picked it up expecting the same standard of proof.Instead, the authors seemed to treat their assertions as unquestionably true.)

After reading this, however, I'm less inclined to think that Cialdini gilded the lily. The main difference is the considerably lower level of self-awareness from the elected officials.

To be blunt, there is no rational way to come away from Musk's tunnel debut more enthusiastic about the project. There was no good news there.

1. The reviews were brutal.

2. The new proposal is slower with much lower capacity than what was promised.

3. After two years of promises, the company appears to have made no technological advances at all. No progress in tunneling techniques. Seemingly no work at all on the rest of the system. Nothing.

We have reached that point in the Musk narrative where what should cause doubt only adds to the faith of the faithful.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Elon Musk's baking soda volcano

As we discussed before in some detail, Elon Musk's proposals can be easily categorized into two groups. The first set are solidly engineered, reasonably viable incremental advances based on standard technological approaches. They are also obviously the work of the many fine scientists and engineers employed by SpaceX and Tesla.

Musk always had a reputation for taking credit for other people's work, and his off script moments over the past few years have made it increasingly clear that the man has a shockingly weak grasp of engineering and cannot possibly contribute to these real projects on anything more than an aesthetics and user experience level. (And yes, that is the same level that Steve Jobs focused on, but Jobs never claimed to be a "real life Tony Stark" despite having a far stronger grasp of the engineering side than what Elon Musk has displayed.)

The second set of ideas apparently do come from Musk himself and they all shared certain common traits. They show a fundamental ignorance of the underlying technology, they are cool and lend themselves to credulous media coverage (it often seems that Musk starts with the CGI animations then throws together a proposal around them), they are orders of magnitude more costly and difficult to implement than Musk suggests and they are invariably derived from familiar postwar science-fiction tropes.

With the debut of the Boring company tunnel, however, we have a new kind of Elon Musk idea, new in a way that raises a number of questions. What reporters saw last week wasn't just a radical departure from the technology that had been promised; it was a completely different kind of Elon Musk proposal. In order to get the full impact of the shift, it's helpful to review what this was supposed to be in the beginning.

The idea was that cars would be carried through a system of underground tunnels using fully automated, high-speed carriers initially termed "sleds." The basic notion isn't all that far from the well-established practice of car-carrying commuter trains, something that might actually be a pretty good idea for certain routes in Los Angeles (it's a very big county and that's not even taking into account the people who drive back and forth from Orange). Between developing the technology, digging the tunnels, and installing the rest of the infrastructure, the cost of this plan would the ludicrously prohibitive, but it would be cool and might even do what it's supposed to in terms of congestion and traffic time.

By going over to the guide-wheels approach that was standard tech in local amusement parks going back to the 50s, the development costs have been largely eliminated, but with them most of the functionality and all of the coolness. The proposed sleds would have been faster and presumably far more maneuverable than individual cars. More importantly, the system would in theory ( and this is all in theory) have been far more reliable. Musk is now proposing a system where any breakdown would freeze up a tunnel for an undetermined period of time. At least based on what we saw last week, removing stalled vehicles from these tunnels is going to be an incredible pain. The result would likely be an even greater tendency toward gridlock than we have now.

Elon Musk has not gotten any better at proposing workable systems, but he still managed to lose his knack for coming up with cool ones. This is a clunky, low-tech "solution" that somehow manages to be both unglamorous and impractical. What happened?

While the following is speculation, it fits the facts and is the pretty much the only explanation I can think of. Musk has had a terrible year and he had locked himself into this demonstration to the extent that backing out would have been a major press fiasco (even worse than what they ended up with). I suspect that at some point fairly recently it became obvious to his team that they would not be able to put together even a crude beta version of the sled, so they opted for the quickest and least sophisticated option, attaching wheels to the sides of a Tesla and simply driving it down the tunnel. The decision appears to have come so late that they didn't even have time to work out a system for retracting the wheels, leaving that instead to the inevitable animation.

Musk is like a school boy who spent the whole semester bragging about the robot he was going to build for the science fair, who then showed up with a project obviously thrown together the night before.

Musk always had a reputation for taking credit for other people's work, and his off script moments over the past few years have made it increasingly clear that the man has a shockingly weak grasp of engineering and cannot possibly contribute to these real projects on anything more than an aesthetics and user experience level. (And yes, that is the same level that Steve Jobs focused on, but Jobs never claimed to be a "real life Tony Stark" despite having a far stronger grasp of the engineering side than what Elon Musk has displayed.)

The second set of ideas apparently do come from Musk himself and they all shared certain common traits. They show a fundamental ignorance of the underlying technology, they are cool and lend themselves to credulous media coverage (it often seems that Musk starts with the CGI animations then throws together a proposal around them), they are orders of magnitude more costly and difficult to implement than Musk suggests and they are invariably derived from familiar postwar science-fiction tropes.

With the debut of the Boring company tunnel, however, we have a new kind of Elon Musk idea, new in a way that raises a number of questions. What reporters saw last week wasn't just a radical departure from the technology that had been promised; it was a completely different kind of Elon Musk proposal. In order to get the full impact of the shift, it's helpful to review what this was supposed to be in the beginning.

The idea was that cars would be carried through a system of underground tunnels using fully automated, high-speed carriers initially termed "sleds." The basic notion isn't all that far from the well-established practice of car-carrying commuter trains, something that might actually be a pretty good idea for certain routes in Los Angeles (it's a very big county and that's not even taking into account the people who drive back and forth from Orange). Between developing the technology, digging the tunnels, and installing the rest of the infrastructure, the cost of this plan would the ludicrously prohibitive, but it would be cool and might even do what it's supposed to in terms of congestion and traffic time.

By going over to the guide-wheels approach that was standard tech in local amusement parks going back to the 50s, the development costs have been largely eliminated, but with them most of the functionality and all of the coolness. The proposed sleds would have been faster and presumably far more maneuverable than individual cars. More importantly, the system would in theory ( and this is all in theory) have been far more reliable. Musk is now proposing a system where any breakdown would freeze up a tunnel for an undetermined period of time. At least based on what we saw last week, removing stalled vehicles from these tunnels is going to be an incredible pain. The result would likely be an even greater tendency toward gridlock than we have now.

Elon Musk has not gotten any better at proposing workable systems, but he still managed to lose his knack for coming up with cool ones. This is a clunky, low-tech "solution" that somehow manages to be both unglamorous and impractical. What happened?

While the following is speculation, it fits the facts and is the pretty much the only explanation I can think of. Musk has had a terrible year and he had locked himself into this demonstration to the extent that backing out would have been a major press fiasco (even worse than what they ended up with). I suspect that at some point fairly recently it became obvious to his team that they would not be able to put together even a crude beta version of the sled, so they opted for the quickest and least sophisticated option, attaching wheels to the sides of a Tesla and simply driving it down the tunnel. The decision appears to have come so late that they didn't even have time to work out a system for retracting the wheels, leaving that instead to the inevitable animation.

Musk is like a school boy who spent the whole semester bragging about the robot he was going to build for the science fair, who then showed up with a project obviously thrown together the night before.

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Monday, December 24, 2018

Do you ever wonder why?

This is Joseph

This move puzzles me, and everyone else I think:

Duncan Black presumed that the target of the tweet was Donald Trump. But why would they be investigating liquidity on a weekend before the holidays? What do they know?

Or are they just really bad at the optics of government and reassuring financial markets?

The net result seems to be some bumpy times in the stock market which seems like the opposite of what the administration would want in the middle of a government shutdown.

What I am missing (flashing the Palko signal into the skies)?

This move puzzles me, and everyone else I think:

For reasons that are a mystery to everyone, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin called up the country’s six biggest banks on Sunday and asked them if their liquidity was OK. Everybody was a bit nonplussed by this, but they said sure, everything’s fine. Any particular reason you’re asking?This was then announced -- publicly.

Duncan Black presumed that the target of the tweet was Donald Trump. But why would they be investigating liquidity on a weekend before the holidays? What do they know?

Or are they just really bad at the optics of government and reassuring financial markets?

The net result seems to be some bumpy times in the stock market which seems like the opposite of what the administration would want in the middle of a government shutdown.

What I am missing (flashing the Palko signal into the skies)?

Friday, December 21, 2018

Thursday, December 20, 2018

The Boring Company's big debut -- even worse than expected.

There was never more than a vanishingly small chance of a major viable advance coming out of this show, but it was at least reasonable to hope for something cool and flashy, like an automated car sled or a ride with some heat. Instead there was nothing, A short narrow tunnel that took over a year to build, traversed by a slow-moving car with guide wheels on the side in an arrangement that sounds remarkably like one of those you-steer-em jalopies that used to be a staple of every cheesy amusement park.

I'll have more thoughts later. In the meantime, check out this rant by Albert Burneko.

Reader, dear reader, I have some great news for you. Tesla’s Elon Musk, definitely a visionary brain genius and not at all a manic idiot spaz and brazen fraud, has invented the future of mass transit for which we so desperately clamored: A narrow, jagged death-tunnel through which, uh, one Tesla-brand car at a time can, ah, drive ... the person who owns it, plus maybe two or three other people ... from one place to another ... at 49 miles per hour.

Okay so wait, I think I’m explaining it wrong. Picture this! It’s, it’s, you see, it’s a subway, only instead of trains filled with many dozens or hundreds of people at a time, riding through a grid of large tunnels, in a grand choreographed underground ballet capable of moving tens or hundreds of thousands of riders per hour, it’s ... Tesla-brand cars ... with their owners and maybe a couple other people ... driving at moderate speed ... through narrow, bumpy tunnels with no emergency exits.

No, goddammit, no, stop looking at me like that, it’s revolutionary technology. It’s high-speed rail, is the thing—only without the high speed, and with the “rail” part kind of arbitrarily added onto what’s otherwise just a single-lane Tesla-only subterranean roadway, for the purpose of securing public investment in it by calling it “mass transit” and not “driving a car from here to there.” And at either end of the trip, instead of just walking into or out of a train station you have to navigate your entire Tesla-brand autonomous electric car down or up a single-car elevator. Also each “train” can only carry as many people as can fit into a single Tesla-brand autonomous electric car.

...

People invented subway trains like 150 years ago, man, you’re saying now. This guy just invented a comically slow-moving conveyor belt for his other company’s cars. Literally the only innovation here is that it’s a worse version of both driving and riding the subway, and only available to people who’ve bought one brand of car. Yes. True. Wait. No. It’s innovative! It’s a solution to the problem of traffic, because now, merely by purchasing a Tesla-brand autonomous electric vehicle and outfitting it with special retractable side-wheels, Tesla owners can bypass gridlock and choose instead to spend their time sitting in the insanely slow-moving line outside of this dumb tunnel, waiting for their turn to go through it, one car at a time.

This isn’t even a good idea for Tesla drivers, you’re saying now. Why would anyone want to make use of this dumb tunnel. We haven’t even really gotten into how even in the press demonstration, it was such an uncomfortable ride that the Washington Post reporter described, in an otherwise not particularly hostile article, as not “an experience you’d tolerate from a public subway service” and which the Los Angeles Times likened to “driving on a dirt road.” Or the danger the stupid aftermarket retractable sideways wheels could pose to other drivers and their ordinary cars if they malfunction. Or the fact that Tesla cars are infamously prone to bursting into flames, which makes them uniquely unsuited to being driven through narrow bumpy tunnels with no room for fire trucks or emergency exits. Or how the planned tunnels are so narrow that even opening a car door inside one looks like a dodgy proposition. Or how even just at the highest conceptual level this is an obviously dumb and pointless idea that even in the absolute best case—which it isn’t presently aiming for—would be redundant to and/or worse than existing rapid-transit rail systems that do not require their riders to own Tesla cars. You’re being a little bit of a jerk right now, to be honest. Why can’t you just get on board with innovation?

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Resisting the urge for an Uber repost.

I'm already having trouble trimming Yves Smith's excellent take-down to excerpt length, so I'll limit myself to links to some similar points we've made in the past.

Ponzi Thresholds

They lose money on every ride but they make it up in volume

Even evil plans require a certain level of competence

A follow-up to Mark's post

And the especially relevant What almost everyone gets wrong about Uber and driverless cars

Uber Is Headed for a Crash

Uber has never presented a case as to why it will ever be profitable, let alone earn an adequate return on capital. Investors are pinning their hopes on a successful IPO, which means finding greater fools in sufficient numbers.

...

Nor, after a certain point, does adding more drivers. Uber does regularly claim that its app creates economies of scale for drivers — but for that to be the case, adding more drivers would have to benefit drivers. It doesn’t. More drivers means more competition for available jobs, which means less utilization per driver. There is a trade-off between capacity and utilization in a transportation system, which you do not see in digital networks. The classic use of “network effects” referred to the design of an integrated transport network — an airline hub and spoke network which create utility for passengers (or packages) by having more opportunities to connect to more destinations versus linear point-to-point routes. Uber is obviously not a fixed network with integrated routes — taxi passengers do not connect between different vehicles.

Nor does being bigger make Uber a better business. As Hubert Horan explained in his series on Naked Capitalism, Uber has no competitive advantage compared to traditional taxi operators. Unlike digital businesses, the cab industry does not have significant scale economies; that’s why there have never been city-level cab monopolies, consolidation plays, or even significant regional operators. Size does not improve the economics of delivery of the taxi service, 85 percent of which are driver, vehicle, and fuel costs; the remaining 15 percent is typically overheads and profit. And Uber’s own results are proof. Uber has kept bulking up, yet it has failed to show the rapid margin improvements you’d see if costs fell as operations grew.

...

Uber has raised an unprecedented $20 billion in investor funding — 2,600 times more than Amazon’s pre-IPO funding. This has allowed Uber to undercut traditional local cab companies, whose fares have to cover all costs, as well as have more cars chasing rides than unsubsidized operators can. Recall that for any transportation service, there is a trade-off between frequency of service and utilization. Having Uber induce more drivers to be on the road to create fast pickups means drivers on average will get fewer fares.

If Uber were to drive all competitors out of business in a local market and then jack up prices, customers would cut back on use. But more important, since barriers to entry in the taxi business are low, and Uber lowered them further by breaking local regulations, new players would come in under Uber’s new price umbrella. So Uber would have to drop its prices to meet those of these entrants or lose business.

Moreover, Uber is a high-cost provider. A fleet manager at a medium-scale Yellow Cab company can buy, maintain, and insure vehicles more efficiently than individual Uber drivers. In addition, transportation companies maintain tight central control of both total available capacity (vehicles and labor) and how that capacity is scheduled. Uber takes the polar opposite approach. It has no assets, and while it can offer incentives, it cannot control or schedule capacity.

The only advantage Uber might have achieved is taking advantage of its drivers’ lack of financial acumen — that they don’t understand the full cost of using their cars and thus are giving Uber a bargain. There’s some evidence to support that notion. Ridester recently published the results of the first study to use actual Uber driver earnings, validated by screenshots. Using conservative estimates for vehicle costs, they found that that UberX drivers, which represent the bulk of its workforce, earn less than $10 an hour. They would do better at McDonald’s. But even this offset to the generally higher costs of fleet operation hasn’t had an meaningful impact on Uber’s economics.

But, you may argue, Uber has all that data about rides! Certainly that allows it to be more efficient than traditional cabs. Um, no. Local ride services have backhaul problems that no amount of cleverness can remedy, like taking customers to the airport and either waiting hours for a return fare or coming back empty, or daily urban commutes, where workers go overwhelmingly in one direction in the morning rush and the other way in the evening. Similarly, Uber’s surge pricing hasn’t led customers to change their habits and shift their trips to lower-cost times, which could have led to more efficient utilization. If Uber had any secret sauce, it would have already shown up in Uber revenues and average driver earnings. Nine years in, and there’s no evidence of that.

...

Uber has gone to some length to avoid publishing financial information on a consistent basis over time, a big red flag. One telling example: In late 2016, Uber targeted a share offering to high-end retail investors, which were presumably even dumber money than the Saudis that had invested in its previous round. Nevertheless, both JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank turned down the “opportunity” to market Uber shares to their clients, even though this could jeopardize their position in a future Uber IPO. Why? The “ride sharing” company supplied 290 pages of verbiage, but not its net income or even annual revenues.

...

But what about driverless cars? Let’s put aside that some enthusiasts like Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak now believe that fully autonomous cars are “not going to happen.” Fully autonomous cars would mean Uber would have to own the cars. The capital costs would be staggering and would burst the illusion that Uber is a technology company rather that a taxi company that buys and operates someone else’s robot cars.

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Monday, December 17, 2018

What would you trade for Friends like these?

I always feel like I should open these Netflix posts with an apology. Much like the Elon Musk thread, I get tired of hearing myself make small refinements on the same points over and over. What's worse, the consistently negative tone probably leaves the wrong impression. Like SpaceX and Tesla, Netflix does more good than harm, providing a very reasonably priced service, producing some fine content, and pumping a great deal of money into the industry.

But one of our main areas of interest here at the blog is the way hype and bad conventional narratives shape our conversation and, again like Elon Musk, Netflix is simply an inescapable example.

I don't know whether the inability to ask the right questions is the result of PR driven narratives or a necessary condition for those narratives to work (or perhaps some combination of the two). Whatever the direction of causality, however, the correlation is certainly remarkable, and never more so than with this company.

Any serious coverage of the viability of Netflix pretty much has to start by asking three things:

What content is driving subscriber growth, pre-existing or original?;

With the original content, exactly what rights has the company acquired?;

Can it ever be anything more than marginally profitable under this model?

On the first point, Netflix has gone to great lengths to suggest that it is their originals that are bringing in the customers. The vast majority of people covering the story have accepted this position uncritically, parroting the PR flacks' talking points. Journalists and analysts gush about the buzz and awards while ignoring the unprecedented promotional budgets. They pass on the company's press releases about viewership for various shows without ever noting that these are self-reported and easily cooked metrics coming from a notoriously opaque company with a history of promoting misleading narratives (go back and check out how many reporters were fooled into thinking that Netflix owned House of Cards).

The press has so internalized the original content narrative that they can report on a story that completely undercuts it without ever noticing the contradiction.

[Using the Marketplace link because it's a good write-up, not because they're an example of the credulous coverage.]

Though there are other potential benefits, the main argument for an independent streaming service such as Netflix making a major investment in original content is that it would bring a degree of independence from the major studios and, among other things, prevent them from extorting huge checks from the company. (You know, like demanding $100 million to license a show for one year.)

The trouble is not only that Netflix isn't there yet, but that it doesn't seem to be getting there. Once again, this is another instance where following the PR dictated narrative is so dangerous. By keeping the conversation focused on the previously mentioned buzz, the huge amounts of money being spent, and the sheer quantity of programs, attention has all but completely been diverted from the actual value of the IP being generated.

The Friends deal suggest a useful way of framing this question: what does Netflix own outright that is worth more than the most valuable properties of Disney/Fox, Warners, and the rest?

For our purposes, most spectacular IP falls into three categories. Friends falls into the first, the previously discussed TV shows with legs. These are series that developed large followings of viewers who have a seemingly unlimited appetite for watching the same episodes again and again often over the space of decades. A Seinfeld or a Big Bang Theory or a Law and Order can bring in hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

This can go on for an amazingly long time. It is entirely possible that the post 2018 IP value of the almost 70-year-old I Love Lucy is worth more than that of any current Netflix or Amazon Prime original. Arguably, the closest contender would be Kimmy Schmidt which appears to be owned largely by NBC/Universal.

We've also discussed the second category, children's programming. Historically, you could make a pretty good case for this being the most lucrative area of television, especially in terms of ROI. It has also been the backbone of every video delivery platform since television became a mass medium in the late 40s. This is always been an underdeveloped area for Netflix. More importantly and in direct contradiction to the official narrative, it is dominated by licensed properties completely owned by major studios.

To date, the highest profile Netflix children's original is the reboot of She-Ra. There is obviously a substantial PR budget behind the show, presumably coming from Netflix despite the fact that it probably doesn't own any real share of the character.

This is a natural segue to the third category of franchises/characters/universes. With a handful of exceptions, the company hasn't even tried to compete in this space despite it being the most talked about and (in terms of absolute numbers if not ROI) by far the biggest.

The closest attempt I can think of was the Will Smith vehicle Bright. That one was launched in 2017 with a big marketing budget and was immediately declared a huge success with the announcement of the sequel coming mere days after the premier. Then, curiously, the normally fast-moving Netflix which desperately needs its own slate of blockbuster franchises decided to put the follow-up on what appears to be a relatively slow track with filming not starting until 2019.

Over the past few years we have seen God knows how many breathless accounts of the billions upon billions of dollars that Netflix has spent on original programming, in articles lousy with references to disruption and visionary leaders, but almost none of these journalists have taken the next obvious step and considered what the company was getting for all that money.

But one of our main areas of interest here at the blog is the way hype and bad conventional narratives shape our conversation and, again like Elon Musk, Netflix is simply an inescapable example.

I don't know whether the inability to ask the right questions is the result of PR driven narratives or a necessary condition for those narratives to work (or perhaps some combination of the two). Whatever the direction of causality, however, the correlation is certainly remarkable, and never more so than with this company.

Any serious coverage of the viability of Netflix pretty much has to start by asking three things:

What content is driving subscriber growth, pre-existing or original?;

With the original content, exactly what rights has the company acquired?;

Can it ever be anything more than marginally profitable under this model?

On the first point, Netflix has gone to great lengths to suggest that it is their originals that are bringing in the customers. The vast majority of people covering the story have accepted this position uncritically, parroting the PR flacks' talking points. Journalists and analysts gush about the buzz and awards while ignoring the unprecedented promotional budgets. They pass on the company's press releases about viewership for various shows without ever noting that these are self-reported and easily cooked metrics coming from a notoriously opaque company with a history of promoting misleading narratives (go back and check out how many reporters were fooled into thinking that Netflix owned House of Cards).

The press has so internalized the original content narrative that they can report on a story that completely undercuts it without ever noticing the contradiction.

[Using the Marketplace link because it's a good write-up, not because they're an example of the credulous coverage.]

Fans of the hit TV show “Friends” were relieved last week to see the sitcom’s 236 episodes will continue streaming on Netflix through 2019. This was made possible by the behemoth of a streaming deal between Netflix and WarnerMedia, which cost the former $80 million to $100 million, according to some reports, to continue licensing the show for 2019. However, some media sources are saying the deal could continue for multiple years after that.

Netflix has licensed “Friends” exclusively since 2015, but the new agreement will remove the exclusive part, allowing WarnerMedia to broadcast the show when the movie and TV company launches its own streaming service next year.

It’s now been more than 14 years since the show’s last air date, but the series is still raking in the dough. That got us to thinking: Just how long has “Friends” been a major moneymaker? So, let’s do the numbers on one of the most successful sitcoms of all time.

...

The cast’s per episode paycheck wasn’t the only dough they were receiving from the show. After season six was over and it was back to the negotiation table, they all started receiving a portion of the show’s syndication profits.

Today, all six of them still receive 2 percent of syndication income, or $20 million each per year, since the show still brings in $1 billion annually for Warner Brothers. Plus, now that the Netflix deal is going through, Aniston, Cox, Kudrow, LeBlanc, Perry and Schwimmer can expect to see even more on their checks from Warner..

Though there are other potential benefits, the main argument for an independent streaming service such as Netflix making a major investment in original content is that it would bring a degree of independence from the major studios and, among other things, prevent them from extorting huge checks from the company. (You know, like demanding $100 million to license a show for one year.)

The trouble is not only that Netflix isn't there yet, but that it doesn't seem to be getting there. Once again, this is another instance where following the PR dictated narrative is so dangerous. By keeping the conversation focused on the previously mentioned buzz, the huge amounts of money being spent, and the sheer quantity of programs, attention has all but completely been diverted from the actual value of the IP being generated.

The Friends deal suggest a useful way of framing this question: what does Netflix own outright that is worth more than the most valuable properties of Disney/Fox, Warners, and the rest?

For our purposes, most spectacular IP falls into three categories. Friends falls into the first, the previously discussed TV shows with legs. These are series that developed large followings of viewers who have a seemingly unlimited appetite for watching the same episodes again and again often over the space of decades. A Seinfeld or a Big Bang Theory or a Law and Order can bring in hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

This can go on for an amazingly long time. It is entirely possible that the post 2018 IP value of the almost 70-year-old I Love Lucy is worth more than that of any current Netflix or Amazon Prime original. Arguably, the closest contender would be Kimmy Schmidt which appears to be owned largely by NBC/Universal.

We've also discussed the second category, children's programming. Historically, you could make a pretty good case for this being the most lucrative area of television, especially in terms of ROI. It has also been the backbone of every video delivery platform since television became a mass medium in the late 40s. This is always been an underdeveloped area for Netflix. More importantly and in direct contradiction to the official narrative, it is dominated by licensed properties completely owned by major studios.

To date, the highest profile Netflix children's original is the reboot of She-Ra. There is obviously a substantial PR budget behind the show, presumably coming from Netflix despite the fact that it probably doesn't own any real share of the character.

This is a natural segue to the third category of franchises/characters/universes. With a handful of exceptions, the company hasn't even tried to compete in this space despite it being the most talked about and (in terms of absolute numbers if not ROI) by far the biggest.

The closest attempt I can think of was the Will Smith vehicle Bright. That one was launched in 2017 with a big marketing budget and was immediately declared a huge success with the announcement of the sequel coming mere days after the premier. Then, curiously, the normally fast-moving Netflix which desperately needs its own slate of blockbuster franchises decided to put the follow-up on what appears to be a relatively slow track with filming not starting until 2019.

Over the past few years we have seen God knows how many breathless accounts of the billions upon billions of dollars that Netflix has spent on original programming, in articles lousy with references to disruption and visionary leaders, but almost none of these journalists have taken the next obvious step and considered what the company was getting for all that money.

Friday, December 14, 2018

Another recently relevant repost

A few months ago we did a post on how certain shows achieve a remarkable longevity, and as a result, bring in a tremendous amount of money. We didn't, however, say how much.

From Marketplace:

I've probably spent too much time on this thread already, but one of these days I ought to do a post on just how problematic the Netflix exclusivity model is, how it goes against the well-established but deeply weird economics of certain nonrival goods. (When increasing supply increases demand, things get very strange very quickly. Insert highly appropriate Twilight Zone reference here.)

For now, we'll focus on one specific corner of the topic, television shows that maintain a viable and highly lucrative syndication presence for decades, often actually growing in popularity since their initial run. I'm not talking about programs that form the basis for reboots or reunions or sequels, but of shows where the original episodes continue to draw large viewerships.

We could have a long interesting discussion on the psychology behind the appeal of the familiar. You probably coulld even come up with a few pretty good research topics on the subject, but I want to keep the focus on the business side. Television became a national mass medium in the late 40s. Within its first decade, it started producing shows like I Love Lucy and Perry Mason, now both over 60 years old, which would continue to maintain a surprisingly steady audience to this day.

The return on investment of these programs is stunning. With a handful of exceptions, all of the following shows turned a nice profit during their original network run. Everything since is gravy.

I Love Lucy

Perry Mason

Leave It to Beaver

The Twilight Zone

The Andy Griffith Show

The Adams Family/the Munsters

Bewitched/I Dream of Jeannie

Star Trek

MASH

Columbo

Taxi

The Cosby show (until recently)/Roseann (until recently)

Golden Girls

Cheers/Frasier

Seinfeld

Friends

.

The Simpsons

.Married with Children

Law and Order/CSI/NCIS

And many others.

Nobody understands the economics of these shows better than Weigel Broadcasting, the company that almost single-handedly developed the entire terrestrial superstation segment of the industry. One of the keys to their extraordinary ratings success has been their knowledgeable and affectionate treatment of the material and their respect for their audience.

From Chicago Magazine:

Nowhere does this come through more than in their stations promos.

Here's Carl Reiner's reaction to one.

.

Here's more from Feder on Weigel's promos.

And here are a few more favorites to close the week.

[And yes, I believe that may be the same set.]

From Marketplace:

Fans of the hit TV show “Friends” were relieved last week to see the sitcom’s 236 episodes will continue streaming on Netflix through 2019. This was made possible by the behemoth of a streaming deal between Netflix and WarnerMedia, which cost the former $80 million to $100 million, according to some reports, to continue licensing the show for 2019. However, some media sources are saying the deal could continue for multiple years after that.

Netflix has licensed “Friends” exclusively since 2015, but the new agreement will remove the exclusive part, allowing WarnerMedia to broadcast the show when the movie and TV company launches its own streaming service next year.

It’s now been more than 14 years since the show’s last air date, but the series is still raking in the dough. That got us to thinking: Just how long has “Friends” been a major moneymaker? So, let’s do the numbers on one of the most successful sitcoms of all time.

...

The cast’s per episode paycheck wasn’t the only dough they were receiving from the show. After season six was over and it was back to the negotiation table, they all started receiving a portion of the show’s syndication profits.

Today, all six of them still receive 2 percent of syndication income, or $20 million each per year, since the show still brings in $1 billion annually for Warner Brothers. Plus, now that the Netflix deal is going through, Aniston, Cox, Kudrow, LeBlanc, Perry and Schwimmer can expect to see even more on their checks from Warner.

Friday, August 17, 2018

Shows with legs – – more background on the Netflix thread (and an excuse for a Friday post of MeTV promos)

I've probably spent too much time on this thread already, but one of these days I ought to do a post on just how problematic the Netflix exclusivity model is, how it goes against the well-established but deeply weird economics of certain nonrival goods. (When increasing supply increases demand, things get very strange very quickly. Insert highly appropriate Twilight Zone reference here.)

For now, we'll focus on one specific corner of the topic, television shows that maintain a viable and highly lucrative syndication presence for decades, often actually growing in popularity since their initial run. I'm not talking about programs that form the basis for reboots or reunions or sequels, but of shows where the original episodes continue to draw large viewerships.

We could have a long interesting discussion on the psychology behind the appeal of the familiar. You probably coulld even come up with a few pretty good research topics on the subject, but I want to keep the focus on the business side. Television became a national mass medium in the late 40s. Within its first decade, it started producing shows like I Love Lucy and Perry Mason, now both over 60 years old, which would continue to maintain a surprisingly steady audience to this day.

The return on investment of these programs is stunning. With a handful of exceptions, all of the following shows turned a nice profit during their original network run. Everything since is gravy.

I Love Lucy

Perry Mason

Leave It to Beaver

The Twilight Zone

The Andy Griffith Show

The Adams Family/the Munsters

Bewitched/I Dream of Jeannie

Star Trek

MASH

Columbo

Taxi

The Cosby show (until recently)/Roseann (until recently)

Golden Girls

Cheers/Frasier

Seinfeld

Friends

.

The Simpsons

.Married with Children

Law and Order/CSI/NCIS

And many others.

Nobody understands the economics of these shows better than Weigel Broadcasting, the company that almost single-handedly developed the entire terrestrial superstation segment of the industry. One of the keys to their extraordinary ratings success has been their knowledgeable and affectionate treatment of the material and their respect for their audience.

From Chicago Magazine:

Still under family ownership more than 40 years after its inception, Weigel Broadcasting stands as the last independent television outfit in the city and one of the last in the country. So while the network affiliates in town (WBBM, WMAQ, WLS) blare forth with new, expensively created fare, Weigel’s channels beam with Sabin’s intuition and pluck. “Neal is doing the best television in Chicago with the least amount of resources and the toughest obstacles,” says the former Chicago Sun-Times columnist and local television/radio sage Robert Feder.

Nowhere does this come through more than in their stations promos.

Here's Carl Reiner's reaction to one.

.

Here's more from Feder on Weigel's promos.

And here are a few more favorites to close the week.

[And yes, I believe that may be the same set.]

Thursday, December 13, 2018

At last, a political scientist protagonist

From This American Life:

Ben Calhoun

This election cycle, it wasn't strange for voters to have to wait for races to be called. Seems like there were so many squeakers. Among the squeakiest, still unresolved a month after the election, North Carolina's 9th congressional district. The district is this long stretch of eight counties along the state's southern border. It's so gerrymandered, it looks like a hockey stick.

In that district, a Republican former Baptist pastor named Mark Harris narrowly beat his Democratic opponent. The Democrat was this Boy Scouty, former Marine named Dan McCready. The margin of victory in that race-- 905 votes-- crazy close, but a win.

Until the North Carolina State Board of Elections had a meeting-- the board is four Democrats, four Republicans, one unaffiliated member-- and the board decided in a bipartisan unanimous vote not to approve the results in the ninth congressional district.Michael Bitzer

That late Tuesday afternoon decision by the board not to certify the ninth really kind of sent shockwaves through the state.Ben Calhoun

This is Michael Bitzer, PolySci professor at Catawba College in North Carolina.Michael Bitzer

To say, this is something that looks pretty serious.Ben Calhoun

Trouble in River City.Michael Bitzer

Yes.Ben Calhoun

Bitzer says he can't remember this ever happening before. It turns out, behind this bipartisan emergency break-throwing-- voter fraud allegations, specifically funny business with mail-in absentee ballots. So Bitzer did what PolySci professors do in a crisis like this. He dove into the data, downloaded it from the state. And in it, he saw one thing that didn't look like the others.

One county, Bladen county, only 19% of the people voting by mail were registered Republicans. But among the mail-in ballots, the Republican candidate got 61% of the vote. Mathematically, this just seems super unlikely. He'd have to win all the Republicans, and all the independents, and some Democrats.

Normally, professors quantify how unusual something is in statistics, standard deviation and that kind of thing. But I have trouble following that.Ben Calhoun

If you were Luke Skywalker in this situation, how big was the disturbance in the force?Michael Bitzer

Alderaan.Ben Calhoun

For those slightly less nerdy than Professor Bitzer and myself, that's the planet that gets destroyed by the Death Star.Ben Calhoun

The destruction of a planet?Michael Bitzer

Yes. And just eyeballing it, this is not normal.Ben Calhoun

So Bitzer writes a blog post explaining what he was reading in the data that most people had not. Then it spreads rapidly through the internet. And then around the same time, news starts to trickle in.

There's stories of voters who say there were people coming and telling them to give them their mail-in absentee ballots before they filled them in. And they handed them over, and then they don't know what happened to their ballot.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)