I always have mixed feelings about jumping on trending topics, but this does relate to at least a couple of our ongoing thread's (and it gave me a couple of good ideas for our Friday videos).

I assume you're already sick of hearing about this anonymous editorial that recently appeared in the New York Times, but if you been off spelunking for the past few days here's an excellent piece of commentary from David Frum and a very good (given that it was so hastily written) monologue from Stephen Colbert.

.

.

First, as many have noted, this is a self-serving and not completely honest piece from an author who unquestionably is trying to serve a personal and partisan agenda. Particularly egregious is the section about not invoking the 25th amendment out of fear of creating a "constitutional crisis." As Colbert points out, taking steps spelled out in the Constitution is by definition a constitutional remedy, not a crisis. Furthermore, there is no conceivable situation where members of the cabinet are justified in undermining an elected president that does not rise to the standard set in the amendment.

[It should be noted that removing a president through these means is more difficult than most people realize, but the relevant aspect here is that a cabinet official is obligated to take these step if he or she is convinced that their boss is a danger to the country.]

Invoking the 25th amendment would, however, create an existential crisis for the Republican Party. The conservative movement has spent the past few decades cultivating what would come to be the Trump voters to serve as useful idiots and cannon fodder. Now the party is completely dependent on them and publicly jettisoning Trump would drive a lasting wedge between the GOP and the voters it needs the most. The results would play out like the collapse of the Whig party with the fast-forward button pressed.

Part of the calculus of the Republicans' approach to Trump has always been weighing the dangers he presents against the agenda items he helps them advance, but events all the past few months have changed the math. The acceleration and metastasizing of the Mueller investigation (particularly to the Southern District of New York), the tell-all book and revelations of widespread covert taping, the opening of the National Enquirer's Trump safe, and the Woodward book along with myriad other bad news stories have combined to make the possibility of a catastrophe-triggering event (a public meltdown and/or collapse, mass sweeping pardons, firing Jeff sessions and ordering that the Mueller investigation be shut down, etc.) far more likely between now and the midterm elections.

It is important to note that the op-ed was timed to come out just before Woodward's book thus making it a "blockbuster" story that didn't actually tell us anything that wasn't about to be a matter of public record. In this context, the piece has to be approached not as an attempt to inform, but as an attempt to put a positive spin on incredibly negative revelations (from an "unsung hero" no less). At this point, the author and his or her party are looking for at least the possibility of a soft landing.

All of this raises serious ethical questions about the New York Times agreeing to publish this while allowing the author to remain anonymous. The gray lady's greatest strength and greatest weakness has long been its journalistic reputation and its resulting symbiotic relationship with the political and business establishment. This relationship has yielded enormous benefits for the paper, making it the default choice for powerful and famous people who want to get their side of the story out, but it has also compromised its editorial standards to an extent where it may actually be doing more damage than good to the discourse.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, September 7, 2018

Thursday, September 6, 2018

Paul Allen's childhood bedroom and other instructive stories.

This Wired article on Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen's attempt to set up a company for launching satellites into orbit contains an almost perfect metaphor for the vanity aerospace industry though the author fails or perhaps chooses not to notice it.

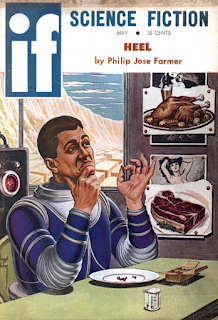

You have here a fantastically wealthy man going to great lengths to recapture childhood dreams. As we've mentioned before and will delve into in greater depth in the future, Silicon Valley futurism is heavily (and I would argue not at all healthily) influenced and bounded by the tropes, rhetoric, and imagery of postwar science-fiction.

Here, the relationship becomes especially obvious when one goes back and studies the probable contents of Allen's boyhood room. Being obsessed with science fiction and a devoted reader of Ley, there was likely a collection of Galaxy Magazines on one of the shelves at some point. There was possibly even a lovingly assembled set of monograms Willy Ley space models hanging from the ceiling.

>.

When you look at the massive aircraft that Allen's company has just introduced and then look at the pictures and stories he obsessed over as a child, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, in a very real sense, he has spent millions upon millions of dollars constructing a life-sized version of the childhood toy.

This is not to say that the approach isn't viable or that the business model is necessarily bad. Air launches are a well established technology and while this proposal does not represent a huge leap forward in low-cost space travel, the suggested economies of scale certainly seem reasonable. God knows we've seen worse business plans recently.

But given the extraordinary role that Silicon Valley culture plays in society and the nearly unchecked power that the super rich wield in the new gilded age, we need to recognize how old most of these ideas are and ask ourselves why aren't we seeing more new ones.

As a teenager, Paul Allen was a sci-fi and rocketry nerd. He dreamed of becoming an astronaut, but that ambition was scuttled by nearsightedness. His childhood bedroom was filled with science fiction and space books. Bill Gates remembers Allen’s obsession. “Even when I first met him—he was in tenth grade and I was in eighth—he had read way more science fiction than anyone else,” says Gates, who later founded Microsoft with Allen. “Way more.” One of Allen’s favorites was a popular science classic called Rockets, Missiles, and Space Travel, by Willy Ley, first published in 1944. As Allen tells it in his memoir, he was crushed when he visited his parents as an adult and went to his old room to reference a book. He discovered that his mother had sold his collection. (The sale price: $75.) Using a blowup of an old photo of the room, Allen dispatched scouts to painstakingly re-create his boyhood library.

You have here a fantastically wealthy man going to great lengths to recapture childhood dreams. As we've mentioned before and will delve into in greater depth in the future, Silicon Valley futurism is heavily (and I would argue not at all healthily) influenced and bounded by the tropes, rhetoric, and imagery of postwar science-fiction.

Here, the relationship becomes especially obvious when one goes back and studies the probable contents of Allen's boyhood room. Being obsessed with science fiction and a devoted reader of Ley, there was likely a collection of Galaxy Magazines on one of the shelves at some point. There was possibly even a lovingly assembled set of monograms Willy Ley space models hanging from the ceiling.

>.

When you look at the massive aircraft that Allen's company has just introduced and then look at the pictures and stories he obsessed over as a child, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, in a very real sense, he has spent millions upon millions of dollars constructing a life-sized version of the childhood toy.

This is not to say that the approach isn't viable or that the business model is necessarily bad. Air launches are a well established technology and while this proposal does not represent a huge leap forward in low-cost space travel, the suggested economies of scale certainly seem reasonable. God knows we've seen worse business plans recently.

But given the extraordinary role that Silicon Valley culture plays in society and the nearly unchecked power that the super rich wield in the new gilded age, we need to recognize how old most of these ideas are and ask ourselves why aren't we seeing more new ones.

Wednesday, September 5, 2018

Revisiting the GOP's 3 x 3 existential threat one year later – – what got left out.

Back in August 2017, we ran a post of arguing that the Republican Party faced a collection of threats that taken together actually had the potential to destroy the party in its current incarnation. I didn't and don't want to spend a lot of time speculating on exactly what form the destruction might take, whether it would be a ground-up rebuilding (possibly combined with a rebranding and name change) for a third party rising up to fill the vacuum or even a split in the remaining party with the more liberal factions setting off on their own while those who stayed drifted to the right, thus making the Democrats the conservative party. Trying to predict where the pieces will fall after an explosion is a sucker's game. I'm just interested in the conditions that make an explosion possible.

With apologies to our regular readers who have seen this too many times before, here's a recap of the basic argument. Under its current system, the United States is effectively locked into a two-party configuration with one party on the left and the other on the right (I stammered a little bit as I dictated this to my laptop. I have huge issues with the traditional political spectrum, but there's no way to avoid it in this context). Furthermore, these two parties are extraordinarily resilient since it is next to impossible, under normal circumstances, for a third party to take the place of one of the main two.

If, however, you have a number of different threats to the party, each at an extreme perhaps even unprecedented level all working in concert, the likelihood of a Whig party scenario is no longer trivial. A year ago, I ran through a list of unpopular policies (healthcare, immigration, tax cuts for the rich), presidential scandals (involving money, collaboration with foreign powers, and obstruction of justice) and demographic challenges (with women, people of color, and younger voters). The range and severity of these threats appear to be something unique in American political history.

On the whole, the list has held up fairly well over the past 12 months, but there are a couple of threats that need to be added even at the risk of spoiling the nice 3 x 3 symmetry. The first is trade, which remains a real surprise for me. True, Trump talked a good protectionist game from the beginning, but he also promised to strengthen the social safety net and raise taxes on the rich. In those areas, any pretense of economic populism was instantly abandoned for conservative orthodoxy. It was only in the area of trade that those campaign promises were not only fulfilled, but doubled down on. It was also difficult to anticipate just how effective China would be at fighting back or how quickly the trade war would become us against the world.

The other omission, and this when I probably should've seen coming, was the role that smaller Republican scandals mostly outside of the administration and often on the state or local level would play. We already did a post on the subject, one which had to be updated almost immediately. This week we had yet another major development from Arkansas, again involving a member of the Hutchinson family dynasty.

Obviously, even with the Hutchinson name attached, this is very much a local story but that does not mean it's an independent event in the larger network of the political landscape. It affects and is affected by other events on the state and national level and if I were a real political scientist, I'd be reading up on concepts like cascading failure and catastrophe theory about now.

The conservative movement created the modern Republican Party much like the deacon built the wonderful one-hoss shay, with each component carefully crafted and supporting all the rest, and while I am certainly not trying to argue by analogy here, it is entirely within the range of possibility that the eventual outcome the same.

With apologies to our regular readers who have seen this too many times before, here's a recap of the basic argument. Under its current system, the United States is effectively locked into a two-party configuration with one party on the left and the other on the right (I stammered a little bit as I dictated this to my laptop. I have huge issues with the traditional political spectrum, but there's no way to avoid it in this context). Furthermore, these two parties are extraordinarily resilient since it is next to impossible, under normal circumstances, for a third party to take the place of one of the main two.

If, however, you have a number of different threats to the party, each at an extreme perhaps even unprecedented level all working in concert, the likelihood of a Whig party scenario is no longer trivial. A year ago, I ran through a list of unpopular policies (healthcare, immigration, tax cuts for the rich), presidential scandals (involving money, collaboration with foreign powers, and obstruction of justice) and demographic challenges (with women, people of color, and younger voters). The range and severity of these threats appear to be something unique in American political history.

On the whole, the list has held up fairly well over the past 12 months, but there are a couple of threats that need to be added even at the risk of spoiling the nice 3 x 3 symmetry. The first is trade, which remains a real surprise for me. True, Trump talked a good protectionist game from the beginning, but he also promised to strengthen the social safety net and raise taxes on the rich. In those areas, any pretense of economic populism was instantly abandoned for conservative orthodoxy. It was only in the area of trade that those campaign promises were not only fulfilled, but doubled down on. It was also difficult to anticipate just how effective China would be at fighting back or how quickly the trade war would become us against the world.

The other omission, and this when I probably should've seen coming, was the role that smaller Republican scandals mostly outside of the administration and often on the state or local level would play. We already did a post on the subject, one which had to be updated almost immediately. This week we had yet another major development from Arkansas, again involving a member of the Hutchinson family dynasty.

Arkansas governor's nephew leaves state Senate amid charges

By ANDREW DeMILLO, Associated Press

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. (AP) — A nephew of Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson resigned from the state Senate on Friday after being charged with spending thousands of dollars in campaign funds on personal expenses, including a Caribbean cruise, tuition payments and groceries, prosecutors announced Friday.

Former state Sen. Jeremy Hutchinson, a Republican who wasn't seeking re-election, is charged with eight counts of wire fraud and four counts of filing false tax returns. Federal prosecutors allege that from 2010 through 2017, he used campaign money to pay for personal expenses that also included Netflix fees, jewelry, a gym membership and his utility bills. They say he tried to hide it by falsifying campaign finance reports and tax filings.

Obviously, even with the Hutchinson name attached, this is very much a local story but that does not mean it's an independent event in the larger network of the political landscape. It affects and is affected by other events on the state and national level and if I were a real political scientist, I'd be reading up on concepts like cascading failure and catastrophe theory about now.

The conservative movement created the modern Republican Party much like the deacon built the wonderful one-hoss shay, with each component carefully crafted and supporting all the rest, and while I am certainly not trying to argue by analogy here, it is entirely within the range of possibility that the eventual outcome the same.

Tuesday, September 4, 2018

A few notes on the Westside scooter invasion

I spend a lot of time on the Westside. The plurality of my LA-based friends live in the area and it's a quick drive from my current residence. Recently the heat wave has also been a big reason to head west – – the beaches are often 20 or 30 degrees cooler than other parts of town – – but things seem to be getting more temperate and I'm hoping for some pleasant weather until the next Santa Anas kick in.

Over the past month, with a suddenness that caught pretty much everyone off guard, the area has seen a swarm of electric scooters. I've dodged the riders in traffic, stepped over the scooters on the sidewalk, and listened to the reactions of the locals (Check here for Ken Levine's), so I thought I'd jot down a few quick thoughts on the subject.

One. This is not a national, or even an LA story; this is a west of Lincoln story.

[for a bit of background, check out this earlier post.]

This tiny strip of the huge city of Los Angeles gets a wildly disproportionate share of attention, at least in part because a large portion of visitors never make it east of the 405 or south of the 105. The New York Times is particularly egregious in this regard (you have to wonder if the phrase "patronizing, provincial asshole" actually appears in the job listing for the papers travel writers). While these scooters are ubiquitous in places like Venice Beach and Santa Monica, it's likely that most LA residents have never actually seen one in their neighborhood.

Two. So far, these scooters thrive in exactly the neighborhoods you would expect them to.

Here in LA (and I believe in the Bay Area as well) scooters are ubiquitous in places that are upscale, dense, well-maintained and policed, and touristy as hell. They appeal most strongly to the kind of people who hang out in these areas, particularly...

Three. Scooting is very much a young person's game.

Of the dozens of people I've seen zipping around various beach communities, I can recall exactly one who appeared to be over 40. The majority appeared to be in their 20s. Part of this can be explained by the appeal of different activities to different age groups, but a lot of it comes down to factors like balance, even more than writing a bicycle. To get on one of these scooters requires one be confident on one's feet, which leads us to the next point...

Four. Scooters are almost exclusively an alternative to walking.

When we discuss electric scooters as a form of transportation, it is important to note that virtually everyone who rides one of these is capable of walking and the vast majority of the trips they take could be done on foot. Bicycles, with their greater range, ability to handle rougher terrain, can be operated reasonably safely at night, and options for hauling cargo, are often a viable alternative to cars, buses, and subways. None of this applies to scooters.

Five. And pedestrians hate them.

It seems a safe bet that most urban transportation experts would argue that we should prioritize pedestrians first with cyclists a close second followed by various forms of public transportation like buses and subways with cars a distant last. Scooters provide an alternative to walking that inconveniences and sometimes endangers pedestrians. The hazards will be difficult to address – – you can make all the rules you want, but scooters are simply better suited for sidewalks than roads – – but the inconvenience could largely be avoided except for...

Six. Ddulite fallacy and the false dichotomy between dockless and nothing.

This goes back to our long running discussion of the profoundly irrational tendency particularly among journalists and investors to reject the tools that are most appropriate for a given job in favor of some shiny new tech. In this case, it is notable how the concept of docking stations have been relegated to the antiquated pile. Keep in mind that almost everyone who would consider using a scooter is capable of walking a few blocks to and from the stations and that having an assigned place for unused scooters would remove most of the complaints about inconvenience.

Seven. But there are hundreds of millions of reasons why we are going to hear a rational conversation on the subject.

Given the limited potential size of this market, the valuation of these companies is absolutely insane. With Uber and Netflix there was at least a highly improbable scenario for justifying the investments and stock prices. With the scooter industry, there's not even that. Nonetheless all of this money means that small armies of lobbyist and PR hacks are currently being marshaled. Already regulations are being captured and journalists are being dictated to. Unquestionably there will be more to this story, but I'm pretty sure it will have a familiar ring to it.

Over the past month, with a suddenness that caught pretty much everyone off guard, the area has seen a swarm of electric scooters. I've dodged the riders in traffic, stepped over the scooters on the sidewalk, and listened to the reactions of the locals (Check here for Ken Levine's), so I thought I'd jot down a few quick thoughts on the subject.

One. This is not a national, or even an LA story; this is a west of Lincoln story.

[for a bit of background, check out this earlier post.]

This tiny strip of the huge city of Los Angeles gets a wildly disproportionate share of attention, at least in part because a large portion of visitors never make it east of the 405 or south of the 105. The New York Times is particularly egregious in this regard (you have to wonder if the phrase "patronizing, provincial asshole" actually appears in the job listing for the papers travel writers). While these scooters are ubiquitous in places like Venice Beach and Santa Monica, it's likely that most LA residents have never actually seen one in their neighborhood.

Two. So far, these scooters thrive in exactly the neighborhoods you would expect them to.

Here in LA (and I believe in the Bay Area as well) scooters are ubiquitous in places that are upscale, dense, well-maintained and policed, and touristy as hell. They appeal most strongly to the kind of people who hang out in these areas, particularly...

Three. Scooting is very much a young person's game.

Of the dozens of people I've seen zipping around various beach communities, I can recall exactly one who appeared to be over 40. The majority appeared to be in their 20s. Part of this can be explained by the appeal of different activities to different age groups, but a lot of it comes down to factors like balance, even more than writing a bicycle. To get on one of these scooters requires one be confident on one's feet, which leads us to the next point...

Four. Scooters are almost exclusively an alternative to walking.

When we discuss electric scooters as a form of transportation, it is important to note that virtually everyone who rides one of these is capable of walking and the vast majority of the trips they take could be done on foot. Bicycles, with their greater range, ability to handle rougher terrain, can be operated reasonably safely at night, and options for hauling cargo, are often a viable alternative to cars, buses, and subways. None of this applies to scooters.

Five. And pedestrians hate them.

It seems a safe bet that most urban transportation experts would argue that we should prioritize pedestrians first with cyclists a close second followed by various forms of public transportation like buses and subways with cars a distant last. Scooters provide an alternative to walking that inconveniences and sometimes endangers pedestrians. The hazards will be difficult to address – – you can make all the rules you want, but scooters are simply better suited for sidewalks than roads – – but the inconvenience could largely be avoided except for...

Six. Ddulite fallacy and the false dichotomy between dockless and nothing.

This goes back to our long running discussion of the profoundly irrational tendency particularly among journalists and investors to reject the tools that are most appropriate for a given job in favor of some shiny new tech. In this case, it is notable how the concept of docking stations have been relegated to the antiquated pile. Keep in mind that almost everyone who would consider using a scooter is capable of walking a few blocks to and from the stations and that having an assigned place for unused scooters would remove most of the complaints about inconvenience.

Seven. But there are hundreds of millions of reasons why we are going to hear a rational conversation on the subject.

Given the limited potential size of this market, the valuation of these companies is absolutely insane. With Uber and Netflix there was at least a highly improbable scenario for justifying the investments and stock prices. With the scooter industry, there's not even that. Nonetheless all of this money means that small armies of lobbyist and PR hacks are currently being marshaled. Already regulations are being captured and journalists are being dictated to. Unquestionably there will be more to this story, but I'm pretty sure it will have a familiar ring to it.

Monday, September 3, 2018

A Labor Day blast from the past

Look for the Union Label

The ILGWU sponsored a contest among its members in the 1970s for an advertising jingle to advocate buying ILGWU-made garments. The winner was Look for the union label.[9][10] The Union's "Look for the Union Label" song went as follows:

Look for the union label

When you are buying a coat, dress, or blouse,

Remember somewhere our union's sewing,

Our wages going to feed the kids and run the house,

We work hard, but who's complaining?

Thanks to the ILG, we're paying our way,

So always look for the union label,

It says we're able to make it in the USA!

The commercial featuring the famous song was parodied on a late-1970s episode of Saturday Night Live in a fake commercial for The Dope Growers Union and on the March 19, 1977, episode (#10.22) of The Carol Burnett Show. It was also parodied in the South Park episode "Freak Strike" (2002).

Friday, August 31, 2018

Friday Pop Culture Corner

John P. Marquand, author of both respected literary novels and the popular Mr. Moto thrillers was said to use those lighter adventure stories as a way of, for lack of a better word, subsidizing the research for his more serious works. Blogs are great for that. Not only do they provide an outlet for all those interesting facts and stray observations that come from laying the groundwork for a longer piece or bigger project; they also are an excellent way of starting a conversation and generating interest for those bigger undertakings.

One of these days, I would like to do a serious deep dive into the current rather sad state of criticism and cultural commentary. I've got plenty of bad examples (I could probably do an entire thread of embarrassing examples from the otherwise essential Lawyers Guns and Money), but I also have at least one very good example, Bob Chipman.

Chipman, who also goes by MovieBob, seems at first glance to be almost a performance art parody of a Boston fan boy. I suspect there is at least a small element of affectation here (it's almost impossible to craft a public persona without it), but most of this is clearly sincere, and those pop culture obsessions are a fundamental part of what makes Chipman so valuable. He understands the fan boy dynamics that drive so much of the entertainment industry (and consequently major segments of our economy). At the same time he has the detachment, self-awareness, and broader literacy to see the big picture (perhaps not coincidentally, the name of his original series of video essays).

I know how improbable this sounds, but having slogged through a swamp of bad Pauline Kael impersonators, the critic I've come across who comes the closest to capturing what made her so important and readable is a minor YouTube celebrity in a donkey Kong T-shirt.

Hopefully, I'll be delving into this deeper at some later point, but for now here are some recent pieces that you might want to check out.

This piece on Disney addresses a couple of extraordinarily important topics, starting out with a discussion of fan conspiracy theories (often with an alt right agenda) about Disney's Star Wars and Marvel Cinematic Universe franchises, then segues into the far more important topic of media consolidation.

As a follow-up, these two videos examine Black Panther both as a film and as a cultural phenomenon.

This account of the firing of James Gunn addresses the increasingly dangerous alt right tactic of launching a social media attack on a progressive figure based on feigned offense over some old tweet or video clip.

I initially planned on doing a post comparing this video essay to the somewhat analogous arguments Andrew Gelman made not long ago about the influence of feminism on his work.

[For those of you who like to stick with text, check out Chipman's website.]

One of these days, I would like to do a serious deep dive into the current rather sad state of criticism and cultural commentary. I've got plenty of bad examples (I could probably do an entire thread of embarrassing examples from the otherwise essential Lawyers Guns and Money), but I also have at least one very good example, Bob Chipman.

Chipman, who also goes by MovieBob, seems at first glance to be almost a performance art parody of a Boston fan boy. I suspect there is at least a small element of affectation here (it's almost impossible to craft a public persona without it), but most of this is clearly sincere, and those pop culture obsessions are a fundamental part of what makes Chipman so valuable. He understands the fan boy dynamics that drive so much of the entertainment industry (and consequently major segments of our economy). At the same time he has the detachment, self-awareness, and broader literacy to see the big picture (perhaps not coincidentally, the name of his original series of video essays).

I know how improbable this sounds, but having slogged through a swamp of bad Pauline Kael impersonators, the critic I've come across who comes the closest to capturing what made her so important and readable is a minor YouTube celebrity in a donkey Kong T-shirt.

Hopefully, I'll be delving into this deeper at some later point, but for now here are some recent pieces that you might want to check out.

This piece on Disney addresses a couple of extraordinarily important topics, starting out with a discussion of fan conspiracy theories (often with an alt right agenda) about Disney's Star Wars and Marvel Cinematic Universe franchises, then segues into the far more important topic of media consolidation.

As a follow-up, these two videos examine Black Panther both as a film and as a cultural phenomenon.

This account of the firing of James Gunn addresses the increasingly dangerous alt right tactic of launching a social media attack on a progressive figure based on feigned offense over some old tweet or video clip.

I initially planned on doing a post comparing this video essay to the somewhat analogous arguments Andrew Gelman made not long ago about the influence of feminism on his work.

[For those of you who like to stick with text, check out Chipman's website.]

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Back on the Musk beat -- actually, the Augean stables part is rather apt

One of the perks of following the recent news around Elon Musk and Tesla motors is the opportunity to observe in detail the performance of a narrative when stressed to the breaking point. We see the limits of its tensile strength, learn to spot the signs of strain.

Of particular interest is the way journalists react to those signs while trying to maintain the basic integrity of the narrative. This entails a strategic retreat on some points, sidestepping others, and holding firm, even doubling down, on the rest.

Take this Wired article by Alex Davies provocatively entitled "Elon Musk Is Broken, and We Have Broken Him." With the important caveat that some of this may be tongue-in-cheek (there are certainly touches of snark which suggests at least the possibility of more subtle sarcasm), here are some illustrative points.

Conceding the obvious first

Even here you have some hedging bordering on distortion. The phrase "more profitable" in particular is pushing things quite a bit. This is true in the mathematical sense – – a positive number is always greater than a negative number – – but it arguably leaves the impression that Tesla is profitable rather than a money losing concern. The real pivot, though, follows in the second half of the paragraph where we it the inevitable mythic aspect of the story.

As long time readers have already guessed, we are about to enter the realm of magical heuristics, sorcery and myth dressed up as business plans and technology. Before we get the good stuff, however, there are some important facts that have to be downplayed.

We get an account of the development of electric vehicles that dismisses everything that came before Tesla as "golf carts." No mention is made of the numerous predecessors or the other companies that were developing competing products in 2003 such as the Nissan Leaf and the Chevy Volt (and before any hands go up, a plug-in hybrid is an electric car with a backup power system). Likewise, TRW fails to make an appearance in the account of the birth of SpaceX. Perhaps my favorite part of the whole piece is this "he wished a hyperloop industry into creation" which manages to combine the heuristic of will (bringing things into existence through focus and faith) with the phrase in "hyperloop industry."

For those who haven't been following the story, there is no Hyperloop industry because there is no hyperloop, and with the possible exception of a glorified amusement park ride in some place like Dubai, there probably never will be. The near universal consensus among independent experts is that the plan is nowhere near viable. At best the companies pursuing this technology are tragically overoptimistic; at worst, it is an enormous scam that is fleecing hundreds of millions of dollars from gullible investors and quite possibly taxpayers in the near future.

Regular readers will also know that we have an ongoing thread at the blog collecting examples of business and technology writing that implicitly and sometimes explicitly owes more to folklore than to what we would normally consider journalism. This article presents a particularly rich vein in this area, having Musk play multiple mythic or archetypal roles ranging from Fisher King to Icarus to questing demigod (actually, I'm not too sure about the first one. It's been decades hence I read any Joseph Campbell and I have a feeling that I've conflated the Arthurian figure with someone else. There's no doubt about the demigod part, however).

Of particular interest is the way journalists react to those signs while trying to maintain the basic integrity of the narrative. This entails a strategic retreat on some points, sidestepping others, and holding firm, even doubling down, on the rest.

Take this Wired article by Alex Davies provocatively entitled "Elon Musk Is Broken, and We Have Broken Him." With the important caveat that some of this may be tongue-in-cheek (there are certainly touches of snark which suggests at least the possibility of more subtle sarcasm), here are some illustrative points.

Conceding the obvious first

On the surface, the implication—nobody else can do this—is nonsense. Lots of people could run Tesla. Starting with the hundreds of capable executives at the world’s automakers, most of which are larger, more efficient, and more profitable than Tesla.

Even here you have some hedging bordering on distortion. The phrase "more profitable" in particular is pushing things quite a bit. This is true in the mathematical sense – – a positive number is always greater than a negative number – – but it arguably leaves the impression that Tesla is profitable rather than a money losing concern. The real pivot, though, follows in the second half of the paragraph where we it the inevitable mythic aspect of the story.

Go a bit deeper though, and you find the truth of the sentiment. Sure, someone might be a better CEO. But there’s no replacing Elon Musk. Because the man is not just a CEO. To many, the man is a legend.

As long time readers have already guessed, we are about to enter the realm of magical heuristics, sorcery and myth dressed up as business plans and technology. Before we get the good stuff, however, there are some important facts that have to be downplayed.

We get an account of the development of electric vehicles that dismisses everything that came before Tesla as "golf carts." No mention is made of the numerous predecessors or the other companies that were developing competing products in 2003 such as the Nissan Leaf and the Chevy Volt (and before any hands go up, a plug-in hybrid is an electric car with a backup power system). Likewise, TRW fails to make an appearance in the account of the birth of SpaceX. Perhaps my favorite part of the whole piece is this "he wished a hyperloop industry into creation" which manages to combine the heuristic of will (bringing things into existence through focus and faith) with the phrase in "hyperloop industry."

For those who haven't been following the story, there is no Hyperloop industry because there is no hyperloop, and with the possible exception of a glorified amusement park ride in some place like Dubai, there probably never will be. The near universal consensus among independent experts is that the plan is nowhere near viable. At best the companies pursuing this technology are tragically overoptimistic; at worst, it is an enormous scam that is fleecing hundreds of millions of dollars from gullible investors and quite possibly taxpayers in the near future.

Regular readers will also know that we have an ongoing thread at the blog collecting examples of business and technology writing that implicitly and sometimes explicitly owes more to folklore than to what we would normally consider journalism. This article presents a particularly rich vein in this area, having Musk play multiple mythic or archetypal roles ranging from Fisher King to Icarus to questing demigod (actually, I'm not too sure about the first one. It's been decades hence I read any Joseph Campbell and I have a feeling that I've conflated the Arthurian figure with someone else. There's no doubt about the demigod part, however).

Musk, then, is Hercules remixed. The greatest of Greek heroes performed his famed labors as penance for killing his children in a fit of insanity. Musk has completed his own labors, landing rockets on boats and delivering a wonderful, affordable, electric car. But the effort seems to have left him mad. And now he threatens to destroy what he has created.

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Pre-existing conditions and medical care

This is Joseph.

We have talked a few times about the issues with medical insurance. We live in a world where, unfortunately, we all age and decay. Over time, we all acquire conditions. It is also the case, in a world where insurance is linked to both employment and the ability to pay, gaps in insurance may occur and/or insurance providers may change.

This makes the question of pre-existing conditions a thorny one. Since the rules against excluding care based on them are under legal assault, there is a new bill to protect them. Unfortunately it doesn't do a great job.

From Michael Hiltzik

If we want to make private insurance work, there has to be a way for people to get coverage for these conditions, unless we want to completely rethink the cost and licensing structure of American medicine (can we outsource medical care to India using robots and teleconferences?).

It is a big deal not to make this mistake.

We have talked a few times about the issues with medical insurance. We live in a world where, unfortunately, we all age and decay. Over time, we all acquire conditions. It is also the case, in a world where insurance is linked to both employment and the ability to pay, gaps in insurance may occur and/or insurance providers may change.

This makes the question of pre-existing conditions a thorny one. Since the rules against excluding care based on them are under legal assault, there is a new bill to protect them. Unfortunately it doesn't do a great job.

From Michael Hiltzik

The measure says that no insurer may reject an insurance applicant based on his or her medical condition or history. But it’s got a loophole that even the dimmest insurance company could drive a hearse through: It doesn’t require that the insurer provide for treatment of the applicant’s preexisting condition.

That makes the bill’s guaranteed access to insurance “something of a mirage,” says Larry Levitt, senior vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Levitt observed on Twitter that “So-called ‘pre-existing condition exclusions’ were common in individual market insurance policies before the ACA, and are also typical in current short-term policies.” At best, they can impose waiting periods for treatment of those conditions; at worst, they exclude coverage permanently.As medical costs rise in the United States, it becomes impossible to self insure against a pre-existing condition at any likely level of total income. So this matters a lot.

If we want to make private insurance work, there has to be a way for people to get coverage for these conditions, unless we want to completely rethink the cost and licensing structure of American medicine (can we outsource medical care to India using robots and teleconferences?).

It is a big deal not to make this mistake.

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

Neil Simon (July 4, 1927 – August 26, 2018) Updated

Some of Simon's funniest work came early in his career.

Posted this haste.

Left out some stuff.

Still in haste, but here are a few quickies.

1. Check out the reference to socialized medicine and more pointedly, the McClellan Committee in the casino episode.

2. Lots of Nat Hiken favorites like Al Lewis and Charlotte Rae pop up.

3. Hiken was way ahead of his time in casting black actors in diverse roles both here and in Car 54.

4. Car 54 had TV's first interracial kiss, despite what Star Trek fans would have you believe.

5. Car 54 was William Faulkner's favorite show.

Posted this haste.

Left out some stuff.

Still in haste, but here are a few quickies.

1. Check out the reference to socialized medicine and more pointedly, the McClellan Committee in the casino episode.

2. Lots of Nat Hiken favorites like Al Lewis and Charlotte Rae pop up.

3. Hiken was way ahead of his time in casting black actors in diverse roles both here and in Car 54.

4. Car 54 had TV's first interracial kiss, despite what Star Trek fans would have you believe.

5. Car 54 was William Faulkner's favorite show.

Monday, August 27, 2018

Don't feel bad if you haven't heard of Ecclesia College (Pat Boone didn't remember it and he's on their board.) -- UPDATED

Ecclesia College appears to have been the Trump University of Bible colleges. The graduation rates and academic standards would have embarrassed a stripmall business school.

The school's board of advisors featured evangelical luminaries like Pat Boone and revisionist historian David Barton, but when the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette contacted the members, Boone's first reaction was that he had never heard of the school. It was only after checking his records that he issued a correction saying that he had agreed to serve though it appears he it never actually attended a meeting or went to the campus. (Barton did know about the school but that may have had something to do with its proposal to name the history building after him.) It would be tempting to put Boone's initial denial down to an octogenarian's lapses in memory if two of the other "members" contacted had not definitively stated that they were not on the board.

All of this would probably have gone unnoticed if not for this

Ecclesia College is a perfect example of something I've been meaning to write about for a while, the potentially big role of small state scandals. As we've mentioned before in other contexts (notably over the air television and the rise of terrestrial superstations), a major source of press dysfunction is the disparity of attention paid to different parts of the country. On one end of the spectrum you have New York City (particularly upscale sections) and more recently San Francisco. Stories of even the most limited local interest in these cities will receive extensive national coverage. On the other end of the spectrum you have rural areas in places like Arkansas or Oklahoma. Stories that primarily affect these areas, even if they collectively affect tens of millions of people and have significant economic, political, or security implications, will go almost completely unnoticed by the national press or a shockingly long period of time.

I keep up with Arkansas because I was raised there, I know the state, and I've kept a number of friends in the area. Recently, when I ask them what's going on back home or when I check out some local media online, the news is of scandals, mostly low to mid level stuff but pervasive and disproportionately Republican. This is remarkably consistent with the picture I'm getting from places like Oklahoma Missouri, etc. It also sounds a lot like the corruption cases we've been hearing about from places like California and New York State.

Taken individually, none of these scandals mean much, but taken collectively they suggest a major underlying problem for the GOP. We could spend endless hours discussing the causes, but the short version is that decades of media manipulation, working the refs, putting party loyalty above all, and tolerating a culture of grift (prominently featuring Arkansas's own Mike Huckabee) has created, if you'll pardon a melodramatic phrase, a culture of corruption in the Republican Party.

When you combine a sense of persecution and entitlement with the knowledge that your party (currently the dominant political party) will watch your back and with the suspicion that the bar is about to close, people will start to bend rules and break laws at an ever accelerating pace. If you then combine that with what is likely to be an unprecedented collection of scandals in the White House, all of those little stories have the potential to add up to a very big one.

UPDATE -- A friend from Arkansas just sent me this link

In the meantime, Oren Paris III, who had been installed as president of Ecclesia College in 1997, took the school from roughly 50 acres at the time of his installation to approximately 200 acres by mid-2005. From 2005 to 2013, Ecclesia did not buy any land. By 2013, according to the website, which has since been scrubbed to remove reference to Oren Paris III’s leadership, Ecclesia and Paris had come up with “extensive plans for future growth and development.” According to the federal indictment, however, it is more accurate to say that Ecclesia (through Paris) had come up with a plan to call Jon Woods to talk about increasing Ecclesia’s participation in the Arkansas General Improvement Fund, using the selling point that Ecclesia “produces graduates that are conservative voters.”

That is probably true; Ecclesia graduates likely do vote conservative for the most part. Thing is, there are barely any graduates. Look at 2016, which the most recent complete data available, for example:

That’s an 11.6% graduation rate, consisting of FIVE graduates in 2016. Five is 11.6% of a class of about 43 students. So, of the 43 students who enrolled at Ecclesia College in 2012, five graduated in 2016.

Not that 2016 was an aberration. Depending on where you look — and depending on whether you are calculating based on 4, 5, or 6 year graduation rates — Ecclesia College consistently has a graduation rate between 6 and 15%. Compare that to some of the schools consistently considered the most difficult for undergrads.

MIT has a graduation rate of 91.6%. Reed College has a graduation rate of 80.6%. Swarthmore? 85%.

So why is Ecclesia’s rate so low? It could have something do with the fact that the 25/75 percentile ACT scores for Ecclesia College are 6 and 9. (For comparison, MIT’s 25/75 are 31/35, and a perfect score is 36.)

11.6% graduation rate is, to put it bluntly, abysmal. That graduation rate, combined with those ACT scores, makes Ecclesia easily the worst college (2- or 4-year) in the entire state.

The school's board of advisors featured evangelical luminaries like Pat Boone and revisionist historian David Barton, but when the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette contacted the members, Boone's first reaction was that he had never heard of the school. It was only after checking his records that he issued a correction saying that he had agreed to serve though it appears he it never actually attended a meeting or went to the campus. (Barton did know about the school but that may have had something to do with its proposal to name the history building after him.) It would be tempting to put Boone's initial denial down to an octogenarian's lapses in memory if two of the other "members" contacted had not definitively stated that they were not on the board.

All of this would probably have gone unnoticed if not for this

On January 4, 2017, Arkansas legislator Micah Neal pleaded guilty to conspiring to direct $600,000 in state government funds to Ecclesia College and another non-profit in exchange for $38,000 in bribes.[1] The plea agreement also singles out the president of the college (Oren Paris III) as being directly involved with the conspiracy.[2]

On March 2, 2017, former State Senator, Jon Woods, was indicted on 13 charges by a grand jury in connection to the kickback and bribery scheme.

Woods is facing 11 counts of honest services wire fraud, one count of money laundering and one count of honest services mail fraud.

The indictment outlined the scheme to steer General Improvement Fund money from the state legislature to projects supported through funding distributed by the Northwest Arkansas Development District.

The indictment also named the president of Ecclesia College in Springdale, Oren Paris III, who is facing nine counts of honest services wire fraud and one count of honest services mail fraud after receiving funding from GIF monies. The college is not listed in the indictment.

An Alma man, Randell G. Shelton Jr., is also listed in the indictment as part of an unnamed consulting company that was used to pay and conceal the kickbacks that Woods and Neal were allegedly receiving.

Both Shelton and Paris initially pleaded not guilty during arraignment hearings.

Paris changed his plea to guilty on April 4, 2018 and resigned as president of Ecclesia College.

Ecclesia College is a perfect example of something I've been meaning to write about for a while, the potentially big role of small state scandals. As we've mentioned before in other contexts (notably over the air television and the rise of terrestrial superstations), a major source of press dysfunction is the disparity of attention paid to different parts of the country. On one end of the spectrum you have New York City (particularly upscale sections) and more recently San Francisco. Stories of even the most limited local interest in these cities will receive extensive national coverage. On the other end of the spectrum you have rural areas in places like Arkansas or Oklahoma. Stories that primarily affect these areas, even if they collectively affect tens of millions of people and have significant economic, political, or security implications, will go almost completely unnoticed by the national press or a shockingly long period of time.

I keep up with Arkansas because I was raised there, I know the state, and I've kept a number of friends in the area. Recently, when I ask them what's going on back home or when I check out some local media online, the news is of scandals, mostly low to mid level stuff but pervasive and disproportionately Republican. This is remarkably consistent with the picture I'm getting from places like Oklahoma Missouri, etc. It also sounds a lot like the corruption cases we've been hearing about from places like California and New York State.

Taken individually, none of these scandals mean much, but taken collectively they suggest a major underlying problem for the GOP. We could spend endless hours discussing the causes, but the short version is that decades of media manipulation, working the refs, putting party loyalty above all, and tolerating a culture of grift (prominently featuring Arkansas's own Mike Huckabee) has created, if you'll pardon a melodramatic phrase, a culture of corruption in the Republican Party.

When you combine a sense of persecution and entitlement with the knowledge that your party (currently the dominant political party) will watch your back and with the suspicion that the bar is about to close, people will start to bend rules and break laws at an ever accelerating pace. If you then combine that with what is likely to be an unprecedented collection of scandals in the White House, all of those little stories have the potential to add up to a very big one.

UPDATE -- A friend from Arkansas just sent me this link

Official: Governor went against advice, signed bill geared toward 1 Arkansas college

Gov. Asa Hutchinson went against the advice of his state budget director when he signed a 2015 bill that would benefit only Ecclesia College in Springdale, the former budget director says.

Friday, August 24, 2018

Daycares and zoning

This is Joseph

[I think driverless cars are a distraction as we don't yet know their net effect on congestion and if we need to do new infrastructure to make them work then it's unclear that this is a different collective action problem then making transit work.]

But the truth is that it is indubitably true that a new daycare is going to make the neighborhood more congested. It is also the case that failing to welcome it will be bad in the long run for everyone in the city. What would be nice is if we could come up with an incentive system that did not reward maximum obstruction. Because being nice about development means you get all of it, under the current system and that isn't great either.

This article points out the problem with urban development and the pressures involved:

Neighborhood residents sparred with the Zoning Board of Adjustment and the project developer over the proposed conversion of a 12,800-square-foot building on 22nd and South Streets into a Goddard School franchise.

“One person complained and said, are we going to have to listen to the sounds of kids laughing and yelling?” developer Jason Nusbaum told Billy Penn. “We could have worse problems.”

While zoning board members ultimately voted to welcome the childcare facility into the tony neighborhood, their unanimous decision did not come without a massive argument about noise, traffic and, of course, parking.Look, one thing that is very clear is that new businesses always have impacts on existing residents and it is never going to be popular to make life a bit harder. I know parking is loathed by a lot of urban development advocates, but it is the lifeblood of how we do efficient transit in the United States. Fixing that is a much bigger issue and involves rethinking transit.

[I think driverless cars are a distraction as we don't yet know their net effect on congestion and if we need to do new infrastructure to make them work then it's unclear that this is a different collective action problem then making transit work.]

But the truth is that it is indubitably true that a new daycare is going to make the neighborhood more congested. It is also the case that failing to welcome it will be bad in the long run for everyone in the city. What would be nice is if we could come up with an incentive system that did not reward maximum obstruction. Because being nice about development means you get all of it, under the current system and that isn't great either.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Hark the Herald Reporters Sing – – another magical heuristics post

I was reading yet another piece talking about how some Silicon Valley/Silicon Beach company was about to do some impossible thing. As I was mentally compiling a list of factual errors, fallacies, and improbabilities, it suddenly struck me that I was approaching the piece from a completely inappropriate framework. This wasn’t an analysis of a business model; it was the foretelling of the coming conquests of great men. The numbers and anecdotes given in the piece were not evidence and context; they were portents.

We’ve certainly discussed the idea that the discourse of the tech industry is rife with the language and imagery of myths and magic, and we haven’t been the only ones to notice (Paul Krugman recently described the rhetoric of crypto currency supporters as “messianic”), but reading that piece I was struck by an implication which I believe had evaded me up to this point. What are the psychological effects of these stories on the people who tell them?

If tech journalists are increasingly inclined to see figures like Elon Musk as messiahs (and if you think this is over the top, go back and read the Rolling Stone cover story), isn’t it inevitable that these journalists who are announcing the coming of these messiahs will start to think of themselves as heralds?

Up until now, we have tended to describe these reporters as conmen or suckers, but just as two categories are not mutually exclusive, neither is this one. If you dig into the history of charlatans, you’ll have no trouble finding promoters who were both willing accomplices and true believers.

I’ve been struggling to explain the seductiveness of the bullshit narratives which has come to dominate our discussion of science and technology. Part of this unquestionably comes down to the appeal of the pitch: the future is not only brighter than you could imagine, it’s also going to be cheap and easily attained and it’s right around the corner. It’s not difficult to imagine people wanting to believe this, but that still doesn’t fully explain how so many smart and skeptical people have fallen for the obvious flimflam and have rejected the rational for the magical heuristics.

I suspect the psychology of the herald plays a large role here. While it certainly doesn’t hurt that these stories are good copy or that these “messiahs” have appropriately majestic lifestyles (sometimes, the next best thing to being rich is hanging out with the rich), but the reporters covering the stories also have the sense of being part of something great even if their role is only to witness and record.

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

The complicated statistics and conflicting objectives of video recommendation algorithms

What is the objective of the algorithm and how do we know if it's achieving that goal? Well, that depends. The things we would really like to know like impact on long-term customer loyalty and retention, particularly in the event of price increases and/or loss of popular content. Unfortunately, getting an answer to this question that does not entail waiting five or 10 years is extremely difficult.

I suspect the most popular alternative would be simply measuring how often customers accept the recommendation, but that metric is deeply problematic even under the best of circumstances and is almost worthless if approached naïvely.

A big part of the problem is that customers almost always walk into the door with some kind of mental queue, albeit often a vague and incomplete one. A recommendation algorithm that does not change that queue in a nontrivial way is a failure, a complete waste of time and money.

[I almost veered off into a discussion of how models and algorithms interact in this situation, but I'm trying to stay on topic and that's a subject that really needs a serious post or perhaps even thread of its own.]

Now we get to the next level of complexity. If you fail to change the queue you accomplish nothing, but if you do change the queue you still don't necessarily accomplish anything of business value. This is where we need to start getting specific about our objectives because there are some perfectly reasonable but contradictory choices to consider

If the sole concern is serving the customer (and serving the customer is never the sole concern) then the goal might be to get the viewers to watch and give a high ratings to shows they were previously unaware of. Another interesting related metric might be to look at before and after ratings, comparing how much they expected to enjoy a program with how much they actually did.

While great for viewers, this can very easily turn around and bite the company in the ass. For example, if Netflix gets viewers interested in classic cinema, they are likely to start migrating to other services with far better cinephile collections. Filmstruck is probably the best-known of these, but here in LA and possibly in your town as well, the public library offers a free streaming service which includes the Criterion Collection, a catalog which Netflix can't possibly compete against.

So chances are the business not only needs to change the queue; it needs to direct the viewers toward certain programs.

Before we pursue this any further, we need to remember that convincing a person to watch a movie or a TV show that he or she is unfamiliar with has never been easy and has grown far more difficult in recent years. For the first three or so decades of television as a mass medium (let's call it 1950 to 1980 just to have some round numbers), you basically had three networks to choose from. Some minor players popped up – – PBS, independent stations, a few abortive attempts at a fourth network – – but most people spent most of their time watching CBS, NBC, or ABC (usually in that order). Simply getting a show on the air guaranteed enough of an audience for word to get around.

If you want to build the IP value of a television show in 2018, the best way to do it is probably still going the route of a prime time network run and a wide syndication release, but that paradigm is clearly fading. Despite what you may have heard, no one has come up with anything close to replacing it. As a result, companies are either relying on established properties that achieved high name recognition status under the old paradigm or are desperately trying to prop up new properties with dump trucks full of marketing and PR money. Under these circumstances, the suggestion that the viewership for the programming being produced by the streaming services is driven by recommendation engines should be taken with extreme skepticism.

Furthermore, at the risk of being cynical, it would probably be a good idea to approach any story about the role of recommendation algorithms in the world of online video with the assumptions that the sources for the stories have a strong incentive spin them a certain way and that there is a very good chance that those sources don't know what they're doing.

I suspect the most popular alternative would be simply measuring how often customers accept the recommendation, but that metric is deeply problematic even under the best of circumstances and is almost worthless if approached naïvely.

A big part of the problem is that customers almost always walk into the door with some kind of mental queue, albeit often a vague and incomplete one. A recommendation algorithm that does not change that queue in a nontrivial way is a failure, a complete waste of time and money.

[I almost veered off into a discussion of how models and algorithms interact in this situation, but I'm trying to stay on topic and that's a subject that really needs a serious post or perhaps even thread of its own.]

Now we get to the next level of complexity. If you fail to change the queue you accomplish nothing, but if you do change the queue you still don't necessarily accomplish anything of business value. This is where we need to start getting specific about our objectives because there are some perfectly reasonable but contradictory choices to consider

If the sole concern is serving the customer (and serving the customer is never the sole concern) then the goal might be to get the viewers to watch and give a high ratings to shows they were previously unaware of. Another interesting related metric might be to look at before and after ratings, comparing how much they expected to enjoy a program with how much they actually did.

While great for viewers, this can very easily turn around and bite the company in the ass. For example, if Netflix gets viewers interested in classic cinema, they are likely to start migrating to other services with far better cinephile collections. Filmstruck is probably the best-known of these, but here in LA and possibly in your town as well, the public library offers a free streaming service which includes the Criterion Collection, a catalog which Netflix can't possibly compete against.

So chances are the business not only needs to change the queue; it needs to direct the viewers toward certain programs.

Before we pursue this any further, we need to remember that convincing a person to watch a movie or a TV show that he or she is unfamiliar with has never been easy and has grown far more difficult in recent years. For the first three or so decades of television as a mass medium (let's call it 1950 to 1980 just to have some round numbers), you basically had three networks to choose from. Some minor players popped up – – PBS, independent stations, a few abortive attempts at a fourth network – – but most people spent most of their time watching CBS, NBC, or ABC (usually in that order). Simply getting a show on the air guaranteed enough of an audience for word to get around.

If you want to build the IP value of a television show in 2018, the best way to do it is probably still going the route of a prime time network run and a wide syndication release, but that paradigm is clearly fading. Despite what you may have heard, no one has come up with anything close to replacing it. As a result, companies are either relying on established properties that achieved high name recognition status under the old paradigm or are desperately trying to prop up new properties with dump trucks full of marketing and PR money. Under these circumstances, the suggestion that the viewership for the programming being produced by the streaming services is driven by recommendation engines should be taken with extreme skepticism.

Furthermore, at the risk of being cynical, it would probably be a good idea to approach any story about the role of recommendation algorithms in the world of online video with the assumptions that the sources for the stories have a strong incentive spin them a certain way and that there is a very good chance that those sources don't know what they're doing.

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

Codetermination

This is Joseph

The new proposal by Elizabeth Warren to introduce codetermination to the United States has certainly engendered a lot of debate. It led to attacks on the plan as a way to nationalize industries. It also led to questions about whether the same goals could be achieved by empowering unions. A lot of this seems to be an innate resistance to any form of wealth redistribution, which is a tough line to hold as wealth inequality increases and we slide into a crisis of affordable housing.

However, I suspect that there is an even bigger piece that is being overlooked. Just consider these two provisions:

Now other policy ideas could achieve the same goals. But this is a rather clever assault on the principle agent problem as regards to corporate free speech.

The new proposal by Elizabeth Warren to introduce codetermination to the United States has certainly engendered a lot of debate. It led to attacks on the plan as a way to nationalize industries. It also led to questions about whether the same goals could be achieved by empowering unions. A lot of this seems to be an innate resistance to any form of wealth redistribution, which is a tough line to hold as wealth inequality increases and we slide into a crisis of affordable housing.

However, I suspect that there is an even bigger piece that is being overlooked. Just consider these two provisions:

40 percent of the directors would be elected by the company’s workforce, with the other 60 percent elected by shareholders.

Corporate political activity would require the specific authorization of both 75 percent of shareholders and 75 percent of board members.This is a nice way to keep corporate free speech but to prevent a small class of managerial executives from controlling the political agenda of the companies. A company is still free to be an advocate for political positions, but they need to build broad stakeholder consensus that this position is in the best interests of the business. For obvious things that impact the business, like bankruptcy laws for banks, this is an easy sell.

Now other policy ideas could achieve the same goals. But this is a rather clever assault on the principle agent problem as regards to corporate free speech.

Monday, August 20, 2018

A few points to remember about the recent (ongoing?) Meltdown of Elon Musk.

[If you haven't been keeping up with the story, here's a good write-up from the superior Times.]

1. First off, we all know that this story about spending every waking hour focusing on Tesla production problems is bullshit on any number of levels but most obviously based on the fixed upper bound of hours in a day. Musk leads a very public life, and even limiting ourselves to that public record, we know that he finds lots of time to support a multi-hour-a-day social media habit, hang out with his popstar girlfriend, play around with miniature flamethrowers and other toys, confidently make dubious proposals involving Hyperloops and tunneling machines and squeeze in a profoundly embarrassing trip to Thailand.

1a. As always, it is important to remember that Elon Musk has a long history of making questionable claims of extraordinary personal accomplishment. From reading the entire encyclopedia as a child to studying martial arts and taking out the school bully with a single punch to spending a month subsisting on hotdogs and oranges to test his self-discipline and ability to live frugally. These stories are difficult to believe individually; taken together, they strain credulity. Despite this, reporters routinely write "Elon Musk did – –" instead of "Elon Musk said he did – –".

1b. Also important to note that, like many conmen and manipulative people, Musk often relies on appeals for sympathy and personal "revelations" to win over listeners and breakdowns skepticism. This is particularly on display in the infamous Rolling Stone cover story.

1c. None of this is all that important for the state of Tesla, but it tells us a great deal about the state of 21st century journalism.

2. Even if the every-waking-hour story were true, it would hardly be addressing the real problems the company is having. Musk has no relevant experience in the field of auto production and he is, as previously mentioned, a terrible engineer. Even as a way of motivating the troops (an area where Musk has shown a natural gift) this is probably a waste of time thanks to his increasingly toxic relationship with Tesla workers. If he actually wanted to solve this problem, rather than pitching a tent on the production line floor, he would be on a plane trying to poach top talent from other companies.

3. The story does, however, make sense when viewed through a framework of magical heuristics. Keep in mind that one of the primary heuristics, especially when dealing with Musk, is the belief that certain chosen ones have the ability to will things into existence. Though this is always couched in the language of science and business, the real precedents are Merlin conjuring a dragon or Yoda levitating a spacecraft. Closely related to this is the heuristic of destiny. Instead of Merlin and Yoda, think Arthur or Harry Potter or perhaps even a more explicitly messianic figure. Musk repeatedly says that, though his burdens are great, he accepts them because there is no one else who can take them from him.

Keeping things in perspective. This interview will not decide Elon Musk's role in Tesla (his tweet about taking the company private might, but that's a topic for another post). The survival of Tesla will not determine the fate of electric vehicles. And while they have an important part to play, electric vehicles will not be the most important factor in the futures of either transportation or climate change. This isn't that big of a story.

It is, however, an instructive one. We live in an age when massive rivers of money are diverted based on hype, credulous journalists and investors, and folklore passing itself off as business plans. The results were never going to be pretty.

1. First off, we all know that this story about spending every waking hour focusing on Tesla production problems is bullshit on any number of levels but most obviously based on the fixed upper bound of hours in a day. Musk leads a very public life, and even limiting ourselves to that public record, we know that he finds lots of time to support a multi-hour-a-day social media habit, hang out with his popstar girlfriend, play around with miniature flamethrowers and other toys, confidently make dubious proposals involving Hyperloops and tunneling machines and squeeze in a profoundly embarrassing trip to Thailand.

1a. As always, it is important to remember that Elon Musk has a long history of making questionable claims of extraordinary personal accomplishment. From reading the entire encyclopedia as a child to studying martial arts and taking out the school bully with a single punch to spending a month subsisting on hotdogs and oranges to test his self-discipline and ability to live frugally. These stories are difficult to believe individually; taken together, they strain credulity. Despite this, reporters routinely write "Elon Musk did – –" instead of "Elon Musk said he did – –".

1b. Also important to note that, like many conmen and manipulative people, Musk often relies on appeals for sympathy and personal "revelations" to win over listeners and breakdowns skepticism. This is particularly on display in the infamous Rolling Stone cover story.

1c. None of this is all that important for the state of Tesla, but it tells us a great deal about the state of 21st century journalism.

2. Even if the every-waking-hour story were true, it would hardly be addressing the real problems the company is having. Musk has no relevant experience in the field of auto production and he is, as previously mentioned, a terrible engineer. Even as a way of motivating the troops (an area where Musk has shown a natural gift) this is probably a waste of time thanks to his increasingly toxic relationship with Tesla workers. If he actually wanted to solve this problem, rather than pitching a tent on the production line floor, he would be on a plane trying to poach top talent from other companies.

3. The story does, however, make sense when viewed through a framework of magical heuristics. Keep in mind that one of the primary heuristics, especially when dealing with Musk, is the belief that certain chosen ones have the ability to will things into existence. Though this is always couched in the language of science and business, the real precedents are Merlin conjuring a dragon or Yoda levitating a spacecraft. Closely related to this is the heuristic of destiny. Instead of Merlin and Yoda, think Arthur or Harry Potter or perhaps even a more explicitly messianic figure. Musk repeatedly says that, though his burdens are great, he accepts them because there is no one else who can take them from him.

Keeping things in perspective. This interview will not decide Elon Musk's role in Tesla (his tweet about taking the company private might, but that's a topic for another post). The survival of Tesla will not determine the fate of electric vehicles. And while they have an important part to play, electric vehicles will not be the most important factor in the futures of either transportation or climate change. This isn't that big of a story.

It is, however, an instructive one. We live in an age when massive rivers of money are diverted based on hype, credulous journalists and investors, and folklore passing itself off as business plans. The results were never going to be pretty.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)