This sketch from the largely forgotten HBO show Likely Stories (h/t Mark Evanier) hasn't agedd that well -- these things seldom do -- but it has some fun moments and it fits nicely with some of our ongoing threads.

A TRIP TO TOMORROW

Likely Stories: "A TRIP TO TOMORROW" from Imagination Productions on Vimeo.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, April 20, 2018

Thursday, April 19, 2018

Electro-culture

We previously discussed Turn of the Century scientists announcing major discoveries only to have the effect sizes later turn out to vanish entirely. This is probably a better example.

Wednesday, April 18, 2018

Remember, billboards are the billboards of the 21st Century

We've been over this before (repeatedly). Virtually every story you read or hear about Netflix -- whether it's a review of a new show, an interview with a star, or a report on an award -- is largely the product of a massive PR campaign. One of the key components of that campaign is the relentless carpet-bombing of LA with billboards and bus signs.

Admittedly, everyone plays this game, but not to the same degree. Among the major networks, spending seems inversely related to success. Little for CBS, more for NBC, but none of them spend that much. Certain cable networks (AMC, FX, TNT) maintain a big presence as do the pay channels (HBO et al.). The biggest players per show and perhaps overall are the streaming services with Netflix leading the pack.

I knew a huge amount of money was being spent on this, but I didn't realize it was this huge. [emphasis added]

Admittedly, everyone plays this game, but not to the same degree. Among the major networks, spending seems inversely related to success. Little for CBS, more for NBC, but none of them spend that much. Certain cable networks (AMC, FX, TNT) maintain a big presence as do the pay channels (HBO et al.). The biggest players per show and perhaps overall are the streaming services with Netflix leading the pack.

I knew a huge amount of money was being spent on this, but I didn't realize it was this huge. [emphasis added]

Netflix is offering $300 million to acquire Regency Outdoor Advertising, a company that owns the familiar billboards along Sunset Strip, at Los Angeles International Airport and near the UCLA campus, Reuters reports.

The streaming TV giant plans to increase spending on marketing its original shows and movies to $2 billion this year, amid growing competition from technology companies such as Amazon.com, Facebook and Hulu, as well as from traditional media companies like Disney that are investing in their own streaming services.

Billboards are clearly part of Netflix’s promotional arsenal, with Sunset Boulevard adorned with images touting Stranger Things and The Crown. Should the transaction be completed, HBO and Showtime would seemingly need to look for other locations to promote its shows.

Tuesday, April 17, 2018

A reply to Kevin Drum

This is Joseph.

Kevin Drum asks:

It also moves the goalposts. If everything is falling apart then it isn't such a crisis if the disrupted industry has teething issues once they strip cash out of it to pay for the heroes who are reinventing the system.

But if current educational systems are doing well, and slowly improving through incremental change, then it is a lot harder to argue that there is a crisis in education, isn't it?

Kevin Drum asks:

So why do we expect reading scores to be skyrocketing in the first place? Why do we almost universally refuse to acknowledge that scores are up at all, let alone up a fair amount? Why are we so determined to believe that kids in the past were better educated than kids today, even though the evidence says nothing of the sort? It is a mystery.My opinion: because there is a lot of money in education and it won't be possible to "disrupt" education and redirect this money if the current system is doing well. Notice how there is always a lot of money in being a disruptive company, at least for the top management (see Uber -- it is clear that it pays better to run Uber than it does to run a traditional Taxi service).

It also moves the goalposts. If everything is falling apart then it isn't such a crisis if the disrupted industry has teething issues once they strip cash out of it to pay for the heroes who are reinventing the system.

But if current educational systems are doing well, and slowly improving through incremental change, then it is a lot harder to argue that there is a crisis in education, isn't it?

Career Thoughts

A few years ago I decided to take some time off and focus on writing. Now, with some big projects either out of the way or nearing completion, I've decided it's a good time to get back into the saddle. I miss the challenge of actually digging into real data and I don't want to let my analytic muscles atrophy.

Most of my experience has been in data mining and predictive modeling primarily with large to very large data sets working in SAS and R with the occasional detour into Python. I've also done some work with text mining and Bayesian networks and would like to explore that area further given the chance.

If you know of a position that sounds like it might be a fit, please contact me at the Gmail address consisting of my first and last name followed by WCSV, no spaces. If you know of someone who might be looking for someone, please feel free to share that contact information.

Thanks and now back to our regularly scheduled blogging.

Most of my experience has been in data mining and predictive modeling primarily with large to very large data sets working in SAS and R with the occasional detour into Python. I've also done some work with text mining and Bayesian networks and would like to explore that area further given the chance.

If you know of a position that sounds like it might be a fit, please contact me at the Gmail address consisting of my first and last name followed by WCSV, no spaces. If you know of someone who might be looking for someone, please feel free to share that contact information.

Thanks and now back to our regularly scheduled blogging.

People in the late 19th century fully expected to be commuting at a hundred miles an hour in the next ten or twenty years...

Remember that. It's going to be important for future discussions.

THE BOYNTON BICYCLE ELECTRIC RAILWAY. Scientific American 1894/02/17

THE BOYNTON BICYCLE ELECTRIC RAILWAY. Scientific American 1894/02/17

Monday, April 16, 2018

An excellent/terrible piece of reporting on crypto currency from the New Yorker.

The article does a superb job getting in the heads of the subjects. The details are sharp and informative and the quotes are often unintentionally revealing. The problem is what the piece doesn't reveal, at least not as plainly as it should.

When telling an account of misguided (and in some cases even delusional) people, there's always a bit of a balancing act between the desire to let the story tell itself and the impulse to jump in and point out important facts. The article (also from the New Yorker) on the essential oil industry that we spent quite a bit of time discussing last year did an almost perfect job maintaining this balance. Between the narrative and context, the damning conclusions were all but inescapable.

Perhaps the problem here is length. The piece is simply too short for the nuanced story it needs to tell. As a result, we get a beautifully drawn picture of a group of people pursuing a dream, but no real indication of how unrealistic and even dangerous that dream is.[emphasis added throughout]

If your goal is to get more women investing in products like Bitcoin, making them better educated about cryptocurrencies and their risks is the opposite of what you want to do. This is one of those points that would make itself in a more nuanced piece but which needs to be spelled out explicitly here. Pretty much any responsible expert will tell you that, in terms of investment, Bitcoin et al. are likely to crash in the fairly near future and have very little chance of recovering even a fraction of their current value (which already represents a serious drop from the peak value). To leave this detail out is like telling a story of pioneers heading west and not mentioning that their route goes through the Donner Pass.

The brevity and lack of context also means that some of the most interesting historical and cultural aspects of the story are hit upon but not delved into. For instance, there's the growing sense (almost always indicative of a dangerous bubble) that the risks of not investing exceed, perhaps by a great margin, the risk of investing, an attitude you'll seldom see more plainly stated than this [again emphasis added]:

Another interesting notion is the idea that schemes which promise the opportunity for anyone who puts up a moderate amount of money to get rich quick are somehow democratic and, more to the point, that criticizing these schemes is somehow undemocratic. If you go back and read a detailed account of the original exploits of Charles Ponzi, you'll see this was a major theme even then.

The potential applications of block chains, the viability of Bitcoin is a currency, the wisdom of investing in cryptocurrencies, and the vague but powerful sense that these things are portents of a wondrous New Age all get mixed up in complex and often contradictory ways. For instance, the promise that some new cryptocurrency will shoot up in value greatly undercuts the idea that it would make a good medium of exchange, but you will see these statements made side-by-side all the time.

Finally, the story basically ignores the disturbing potential social costs of the Bitcoin bubble. Of course, any time you promote shady, get rich quick investments, you are likely to drive a significant group of people into financial ruin. In this sense, promoting the bubble is a bit like telling poor people to spend more of their income on lottery tickets. There is, however, one important difference. As a rule, at least some of the money collected for a chance at mega millions goes to things like education and infrastructure. That Bitcoin investment is doing this....

When telling an account of misguided (and in some cases even delusional) people, there's always a bit of a balancing act between the desire to let the story tell itself and the impulse to jump in and point out important facts. The article (also from the New Yorker) on the essential oil industry that we spent quite a bit of time discussing last year did an almost perfect job maintaining this balance. Between the narrative and context, the damning conclusions were all but inescapable.

Perhaps the problem here is length. The piece is simply too short for the nuanced story it needs to tell. As a result, we get a beautifully drawn picture of a group of people pursuing a dream, but no real indication of how unrealistic and even dangerous that dream is.[emphasis added throughout]

Between mid-December and early February, bitcoin lost more than half its value, dropping from a high of nearly twenty thousand dollars to just below seven thousand. Depending on whom you asked, it was either a catastrophe—a portent of things to come—or a rare opportunity. Anthony Pompliano, a venture capitalist who is prone to posting bullish, cryptocurrency-related aphorisms on Twitter (“Bitcoin is the ultimate test of someone’s imagination”), reassured his eighty-three thousand followers that it was almost certainly the latter. “This may be the first real ‘crypto recession,’ ” he wrote. “Those that stick around will be rewarded immensely.”

...

By many counts, “literally every guy in crypto” is pretty much everyone in crypto, at least for the time being. A handful of surveys and studies estimate that women make up somewhere between four and sixteen per cent of cryptocurrency investors. Morin, during her introductory remarks, explained that she had heard the four-per-cent figure over the recent winter holidays, when bitcoin was valued at nearly twenty thousand dollars. Part of the problem, she determined, was a paucity of educational resources for women about the fundamentals, and risks, of investing in cryptocurrencies. “We have an opportunity to rebuild the financial system,” Morin said, quoting Galia Benartzi, the co-founder of Bancor, a cryptocurrency protocol; protocols, like Bitcoin or Ethereum, enable decentralized networks of computers to collaborate in maintaining a shared history of immutable transactions, known as the blockchain. “Are we going to do it with all guys again?”

If your goal is to get more women investing in products like Bitcoin, making them better educated about cryptocurrencies and their risks is the opposite of what you want to do. This is one of those points that would make itself in a more nuanced piece but which needs to be spelled out explicitly here. Pretty much any responsible expert will tell you that, in terms of investment, Bitcoin et al. are likely to crash in the fairly near future and have very little chance of recovering even a fraction of their current value (which already represents a serious drop from the peak value). To leave this detail out is like telling a story of pioneers heading west and not mentioning that their route goes through the Donner Pass.

The brevity and lack of context also means that some of the most interesting historical and cultural aspects of the story are hit upon but not delved into. For instance, there's the growing sense (almost always indicative of a dangerous bubble) that the risks of not investing exceed, perhaps by a great margin, the risk of investing, an attitude you'll seldom see more plainly stated than this [again emphasis added]:

Though the speakers emphasized, for legal reasons, that they were not offering financial advice, the general consensus on how to participate wasn’t particularly novel: buy a little bitcoin (“as much as you feel comfortable never seeing again,” Alexia Bonatsos, a venture capitalist, advised); start experimenting with different wallets (the ways, or places, to securely store one’s public and private keys, used to send and receive currency); and play the long game. Take advantage of resources, such as Linda Xie’s guides to cryptoassets and Laura Shin’s “Unchained” podcast, and ask knowledgeable friends for access to Listservs and online communities—in short, network and Google. (It doesn’t hurt to have some technical know-how; for security reasons, it’s safer to have a hardware or paper wallet than to use the more user-friendly platforms recommended by Morin and Bonatsos, like Coinbase or Robinhood.) “Think, obviously, about the risk of what you’re putting in,” Simpson said. “But really think about what is the risk of not investing, and not learning and not participating. Because I think, over a period of decades, if you invest the time, invest money, and start really participating, you will do well.”

Another interesting notion is the idea that schemes which promise the opportunity for anyone who puts up a moderate amount of money to get rich quick are somehow democratic and, more to the point, that criticizing these schemes is somehow undemocratic. If you go back and read a detailed account of the original exploits of Charles Ponzi, you'll see this was a major theme even then.

There is something utopian, and appealing, about the potential for cryptocurrency to provide an opportunity for more equitable wealth distribution.In addition to the standard bullshit stories people tell themselves about implausible get rich quick schemes, cryptocurrencies bring with them all the hype and magical heuristics we would expect from Silicon Valley.

...

Cryptocurrency is the closest thing they have to employee equity, itself a speculative asset; it’s their opportunity to be in the right place at the right time. They’re largely writers and academics, activists and artists, even some tech workers looking for a change.

“It just can’t happen that we have another wave of technical innovation happen, and that all of society is not participating,” he said. “I think that means both men and women; I think that means, you know, people in cities and people in rural areas. This technology is so profound, on so many levels, that it feels really important to educate everyone about it.” By his account, it wasn’t just about the money: the blockchain—that ledger of permanently documented exchanges, which is distributed by participants in a given protocol’s network—has far greater implications. He suggested that other transactions could move to the blockchain, eliminating flurries of paperwork, and intermediaries, as well as increasing the digital security and privacy of all parties; he gave the examples of buying real estate and negotiating venture-capital contracts. (In 2017, women-founded companies accounted for just over four per cent of venture capital deals, and received about two per cent of that year’s venture funding, according to Fortune magazine.) And yet speculation about the possibilities of the blockchain have a tendency to turn cypherpunk. “We all use things like social capital, and love, and empathy,” Dave Morin said. “Most of those ways that we interact have not been turned into money, or haven’t been turned into a currency of any kind. It’s the first time in history that we’re taking all these things that have not been a currency in the past, and turning them into currencies that can be exchanged in various different ways.”

The potential applications of block chains, the viability of Bitcoin is a currency, the wisdom of investing in cryptocurrencies, and the vague but powerful sense that these things are portents of a wondrous New Age all get mixed up in complex and often contradictory ways. For instance, the promise that some new cryptocurrency will shoot up in value greatly undercuts the idea that it would make a good medium of exchange, but you will see these statements made side-by-side all the time.

Finally, the story basically ignores the disturbing potential social costs of the Bitcoin bubble. Of course, any time you promote shady, get rich quick investments, you are likely to drive a significant group of people into financial ruin. In this sense, promoting the bubble is a bit like telling poor people to spend more of their income on lottery tickets. There is, however, one important difference. As a rule, at least some of the money collected for a chance at mega millions goes to things like education and infrastructure. That Bitcoin investment is doing this....

A disused coal power station will reopen to solely power crypto by Swapna Krishna

A closed-down coal plant in Australia's Hunter Valley, about a two-hour drive north of Sydney, is reopening in order to provide inexpensive power for Bitcoin miners. A tech company called IOT Group has partnered with the local power company to revive the power plant and set up cryptocurrency mining operations, called a Blockchain Operations Centre, inside it. This would give the group direct access to energy at wholesale prices.

According to The Age, the Hunter Valley coal power plant was closed back in 2014. Hunter Energy plans to restart the generator in early 2019. The company understands the demands of cryptocurrency mining, and hopes to make the power plant even more attractive to tech companies by adding cleaner energy sources, such as solar power or batteries.

Cryptocurrency mining is an incredibly power-intensive process. It involves using energy hungry computers to solve complex problems, generating intense amounts of heat and using quite a bit of electricity. As a result, miners and mining companies have been on the hunt for inexpensive electricity. Operating from within a coal plant meets that requirement for sure.

Saturday, April 14, 2018

Asking a favor from our regular readers

I realized recently that my networking skills (which weren't that strong to begin with) have atrophied while I've been focusing on writing. As a partial remedy, I thought I'd invite all of our regulars to connect with me on the big business networking site (the one that starts with an L). Just mention you're a reader of the blog.

Thanks,

Mark

p.s. The following has nothing to do with the post. I just thought we needed a picture. (from Galaxy Magazine June 1951)

Thanks,

Mark

p.s. The following has nothing to do with the post. I just thought we needed a picture. (from Galaxy Magazine June 1951)

Friday, April 13, 2018

"They've given you a number, and taken away your name."

I've been trying to to trace back the origins of the science fiction trope of giving futuristic characters numerical names, usually for dystopian or (in the case of W. H. Auden's Unknown Citizen a.k..a. JS/07 M 378) satiric effects, particularly of the practice of reducing people to data points. In Auden's poem, it was the bureau of statistics that singled out the modern-day saint. .

However, the earliest example I can come up with was by no means dystopian or saatiric.

Since we like to close the week on a musical note.

The title quote, by the way, comes from the theme used for the American airings of that show's predecessor.

And, while we're at it, here's the original theme

However, the earliest example I can come up with was by no means dystopian or saatiric.

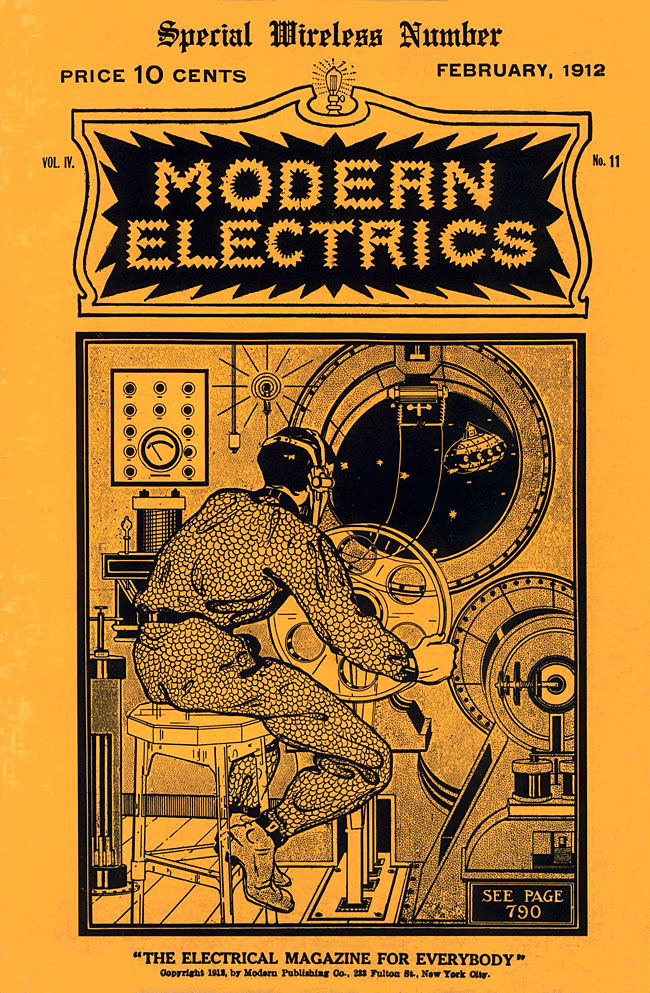

Ralph 124C 41+, by Hugo Gernsback, is an early science fiction novel, written as a twelve-part serial in Modern Electrics magazine beginning in April 1911. It was compiled into novel/book form in 1925. While one of the most influential science fiction stories of all time, modern critics tend to pan the novel and few people read it today. The title itself is a play on words, ( 1 2 4 C 4 1 + ) meaning "One to foresee for one another".

Since we like to close the week on a musical note.

The title quote, by the way, comes from the theme used for the American airings of that show's predecessor.

And, while we're at it, here's the original theme

Thursday, April 12, 2018

In case you were wondering what journalists learned from the Mars One fiasco, the answer is nothing.

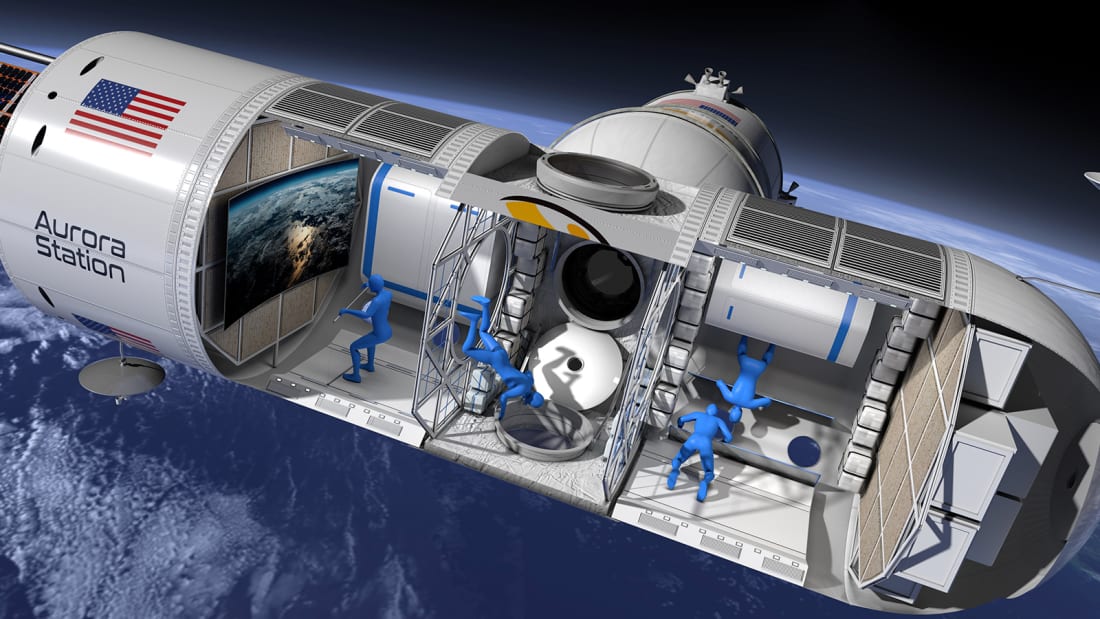

Our most recent piece of evidence:

First luxury hotel in space announced

Note all the standard elements, the outlandish claims, the ridiculous timeline, the lack of credible supporting evidence, the vague plans compensated for by pretty graphics, the claims of enormous gains in efficiency and cost reduction backed by nothing, all credulously reported.

Recently tourism has come to play much the same role for space boosters that it does for chambers of commerce in economically depressed regions, and for some of the same reasons. There's a simplicity and generality that can almost make it seem like a panacea. We need money so will just get people to pay us to come here. The trouble is, of course, that while there is a great deal of money in being a tourist destination, it is remarkably difficult become one.

With space tourism there's the additional problem of the disconnect between the reality of space travel and the decades of accumulated fantasy. The problem is, in a way, analogous to that described in the This American Life episode "Put a Bow on It." It's not enough to come up with a product that sounds interesting; you have to come up with one that sounds interesting and keeps people coming back.

As we've previously mentioned, when someone who has no relevant experience or specific innovations to point to claims to be able to do something at a fraction of the time and cost, you should generally assume the claims are bullshit until proven otherwise, but even if we take the claims at face value, we are still talking about millions of dollars, months of training, and no guarantee of safety in order to spend a few days in zero gravity and see a truly spectacular view. There are those who would gladly give their life savings for such an experience, but I very much doubt there are enough of these people (at least among those whose life savings could buy the ticket) to make a viable industry.

One of the hard lessons of the Apollo Program was that the novelty wears off quickly. A real plan for exploring space has got to start with a real foundation.

First luxury hotel in space announced

CNN — Want to see 16 sunrises in one day? Float in zero gravity? Be one of the few to have gazed upon our home planet from space?

In just four years' time, and for an astronomical $9.5 million dollars, it's claimed you can.

What's being billed as the world's first luxury space hotel, Aurora Station, was announced Thursday at the Space 2.0 Summit in San Jose, California.

Developed by US-based space technology start-up Orion Span, the fully modular space station will host six people at a time, including two crew members, for 12-day trips of space travel. It plans to welcome its first guests in 2022.

"Our goal is to make space accessible to all," Frank Bunger, CEO and founder of Orion Span, said in a statement. "Upon launch, Aurora Station goes into service immediately, bringing travelers into space quickly and at a lower price point than ever seen before."

...

While a $10 million trip is outside the budget of most people's two-week vacations, Orion Span claims to offer an authentic astronaut experience.

Says Bunger, it has "taken what was historically a 24-month training regimen to prepare travelers to visit a space station and streamlined it to three months, at a fraction of the cost."

Note all the standard elements, the outlandish claims, the ridiculous timeline, the lack of credible supporting evidence, the vague plans compensated for by pretty graphics, the claims of enormous gains in efficiency and cost reduction backed by nothing, all credulously reported.

Recently tourism has come to play much the same role for space boosters that it does for chambers of commerce in economically depressed regions, and for some of the same reasons. There's a simplicity and generality that can almost make it seem like a panacea. We need money so will just get people to pay us to come here. The trouble is, of course, that while there is a great deal of money in being a tourist destination, it is remarkably difficult become one.

With space tourism there's the additional problem of the disconnect between the reality of space travel and the decades of accumulated fantasy. The problem is, in a way, analogous to that described in the This American Life episode "Put a Bow on It." It's not enough to come up with a product that sounds interesting; you have to come up with one that sounds interesting and keeps people coming back.

As we've previously mentioned, when someone who has no relevant experience or specific innovations to point to claims to be able to do something at a fraction of the time and cost, you should generally assume the claims are bullshit until proven otherwise, but even if we take the claims at face value, we are still talking about millions of dollars, months of training, and no guarantee of safety in order to spend a few days in zero gravity and see a truly spectacular view. There are those who would gladly give their life savings for such an experience, but I very much doubt there are enough of these people (at least among those whose life savings could buy the ticket) to make a viable industry.

One of the hard lessons of the Apollo Program was that the novelty wears off quickly. A real plan for exploring space has got to start with a real foundation.

Wednesday, April 11, 2018

"EMPLOYMENT OF HIGH-FREQUENCY CURRENTS IN THERAPEUTICS."

I was about to start speculating about the propensity of Turn of the Century scientists to announce major discoveries only to have the effect sizes later turn out to vanish entirely, but then I realized I wasn't entirely sure that this was the case here.

I'm almost certain that this belongs in the same file with N-rays, but given the readership of this, I want to be extra careful.

From Scientific American 1907-08-24

I'm almost certain that this belongs in the same file with N-rays, but given the readership of this, I want to be extra careful.

From Scientific American 1907-08-24

The patient is seated on a chair inside of a spiral coil of wire which is traversed by high-frequency currents. (Fig. 1.) The cabinet shown at the right of the photograph contains a transformer, which gives to the alternating current a tension 01 40,000 or 50,000 volts and a frequency of 500,000 or 600,000 alternations per second. This treatment, continued' for five minutes, reduced the arterial pressure from 10 to 7 inches. In a second treatment, given to the same patient a few days later, the arterial pressure, which had risen during the inteI val to 8 inches, was brought down below 7 inches in a few minutes. Repeated applications gradually reduce the arterial pressure to its normal value of 6 inches. In Dr. Moutier's very interesting experiments, the rapidity with which the pressure was lowered appeared to have no relation to the age or. gravity of the case, or the degree of hypertension, but to depend chiefly on the state of digestion.

Tuesday, April 10, 2018

It's a shame "stentor" didn't catch on

One of the conclusions I've come to after digging though the history of 19th and 202th Century technology is that when there's a real demand for specific functionality, it will express itself as soon as (and sometimes even before) the technology is viable.

Today's example: the news broadcast.

From Scientific American 1907/06/22

Monday, April 9, 2018

"East of Lincoln"

I've never been a beach person. There are (or at least used to be) some exceptions but most of these towns are for me nice places to visit but a little too bland and way too pricey to want to live there.

I know people, however, who have trouble imagining living anywhere else. One of them, a long time Venice resident, described it like this. He had lived in other parts of the city when he first came here but said he never felt he was truly in LA until he made it all the way west. He compared the feeling to that of a pioneer crossing the continent in a covered wagon only to die of thirst in the desert just short of California.

Venice Beach used to have a seedy, bohemian reputation, just the sort of place you'd expect Jim Morrison to hang out. These days, the feel is definitely upscale, the rough edges have largely been worn away, and the crime you encounter is less likely to involve gangs and drugs and more likely to involve Silicon Beach Ponzi schemes.

One of the last holdouts of old Venice was Abbott's Habit, a decidedly non-corporate coffeehouse that long held a corner of Abbott Kinney, the street now known for pop-up shops, trendy restaurants, and places where you can get bone marrow ice cream (no, really).

I happened to be in Venice the day that Abbott's Habit closed. It was packed with regulars as a long list of local musicians played short sets to say goodbye. One song in particular captured the mood of the event (I'm sure it's out there somewhere on the Internet but I haven't been able to find it). The chorus went something like this, "when I get east of Lincoln, my heart starts sinkin'."

The Lincoln in question is the stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway that runs north and south through that part of town and informally divides the "beach" community from the "non-beach" areas. To live west of Lincoln means to have cool ocean breezes throughout the summer, to be able to walk down to the boardwalk, and generally to feel yourself part of the vibe.

Every time the singer got the chorus, the crowd nodded in melancholy appreciation. This was a big part of how they had defined their community and, to a degree, themselves. Now, many were being priced out of the area and, more importantly, those who stayed or returned for a visit knew that their Venice was gone regardless.

While it certainly lacks the emotional resonance for the new residents, "west of Lincoln" has never had more economic importance and perhaps never more social value. Venice Beach has become one of those places where well-off people want to live and, more to the point, one of those places where well-off people want to brag about living. There's nothing especially objectionable about this (most non-native born Angelenos have at least occasionally taken a certain pleasure in telling friends back east stories of beautiful weather and celebrity encounters), but it can have important implications for our urban planning discussion.

Many of the arguments we hear about density and transportation are strongly dependent on some rather simplistic assumptions about linear relationships and fixed demand. Why people live where they live is almost always complicated and seldom monocausal. If the discussion doesn't start reflecting some of that complexity, we are in danger of making some very big mistakes.

(And, yes, the bone marrow ice cream wasn't that bad.)

I know people, however, who have trouble imagining living anywhere else. One of them, a long time Venice resident, described it like this. He had lived in other parts of the city when he first came here but said he never felt he was truly in LA until he made it all the way west. He compared the feeling to that of a pioneer crossing the continent in a covered wagon only to die of thirst in the desert just short of California.

Venice Beach used to have a seedy, bohemian reputation, just the sort of place you'd expect Jim Morrison to hang out. These days, the feel is definitely upscale, the rough edges have largely been worn away, and the crime you encounter is less likely to involve gangs and drugs and more likely to involve Silicon Beach Ponzi schemes.

One of the last holdouts of old Venice was Abbott's Habit, a decidedly non-corporate coffeehouse that long held a corner of Abbott Kinney, the street now known for pop-up shops, trendy restaurants, and places where you can get bone marrow ice cream (no, really).

I happened to be in Venice the day that Abbott's Habit closed. It was packed with regulars as a long list of local musicians played short sets to say goodbye. One song in particular captured the mood of the event (I'm sure it's out there somewhere on the Internet but I haven't been able to find it). The chorus went something like this, "when I get east of Lincoln, my heart starts sinkin'."

The Lincoln in question is the stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway that runs north and south through that part of town and informally divides the "beach" community from the "non-beach" areas. To live west of Lincoln means to have cool ocean breezes throughout the summer, to be able to walk down to the boardwalk, and generally to feel yourself part of the vibe.

Every time the singer got the chorus, the crowd nodded in melancholy appreciation. This was a big part of how they had defined their community and, to a degree, themselves. Now, many were being priced out of the area and, more importantly, those who stayed or returned for a visit knew that their Venice was gone regardless.

While it certainly lacks the emotional resonance for the new residents, "west of Lincoln" has never had more economic importance and perhaps never more social value. Venice Beach has become one of those places where well-off people want to live and, more to the point, one of those places where well-off people want to brag about living. There's nothing especially objectionable about this (most non-native born Angelenos have at least occasionally taken a certain pleasure in telling friends back east stories of beautiful weather and celebrity encounters), but it can have important implications for our urban planning discussion.

Many of the arguments we hear about density and transportation are strongly dependent on some rather simplistic assumptions about linear relationships and fixed demand. Why people live where they live is almost always complicated and seldom monocausal. If the discussion doesn't start reflecting some of that complexity, we are in danger of making some very big mistakes.

(And, yes, the bone marrow ice cream wasn't that bad.)

Friday, April 6, 2018

Repost: Facebook's culture of unaccountability owes a lot to years of credulous coverage from places like the New York Times. (Why we need Gawker part 4,732)

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

"How To Party Your Way Into a Multi-Million Dollar Facebook Job" -- the sad state of business journalism

Andrew Gelman (before his virtual sabbatical) linked to this fascinating Gawker article by Ryan Tate:If you want Facebook to spend millions of dollars hiring you, it helps to be a talented engineer, as the New York Times today [18 May 2011] suggests. But it also helps to carouse with Facebook honchos, invite them to your dad's Mediterranean party palace, and get them introduced to your father's venture capital pals, like Sam Lessin did. Lessin is the poster boy for today's Times story on Facebook "talent acquisitions." Facebook spent several million dollars to buy Lessin's drop.io, only to shut it down and put Lessin to work on internal projects. To the Times, Lessin is an example of how "the best talent" fetches tons of money these days. "Engineers are worth half a million to one million," a Facebook executive told the paper.To get the full impact, you have to read the original New York Times piece by Miguel Helft. It's an almost perfect example modern business reporting, gushing and wide-eyed, eager to repeat conventional narratives about the next big thing, and showing no interest in digging for the truth.

We'll let you in on a few things the Times left out: Lessin is not an engineer, but a Harvard social studies major and a former Bain consultant. His file-sharing startup drop.io was an also-ran competitor to the much more popular Dropbox, and was funded by a chum from Lessin's very rich childhood. Lessin's wealthy investment banker dad provided Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg crucial access to venture capitalists in Facebook's early days. And Lessin had made a habit of wining and dining with Facebook executives for years before he finally scored a deal, including at a famous party he threw at his father's vacation home in Cyprus with girlfriend and Wall Street Journal tech reporter Jessica Vascellaro. (Lessin is well connected in media, too.) . . .

It is not just that Helft failed to do even the most rudimentary of fact-checking (twenty minutes on Google would have uncovered a number of major holes); it is that he failed to check an unconvincing story that blatantly served the interests of the people telling it.

Let's start with the credibility of the story. While computer science may well be the top deck of the Titanic in this economy, has the industry really been driven to cannibalization by the dearth of talented people? There are certainly plenty of people in related fields with overlapping skill sets who are looking for work and there's no sign that the companies like Facebook are making a big push to mine these rich pools of labor. Nor have I seen any extraordinary efforts to go beyond the standard recruiting practices in comp sci departments.

How about self-interest? From a PR standpoint, this is the kind of story these companies want told. It depicts the people behind these companies as strong and decisive, the kind of leaders you'd want when you expect to encounter a large number of Gordian Knots. When the NYT quotes Zuckerberg saying “Someone who is exceptional in their role is not just a little better than someone who is pretty good. They are 100 times better,” they are helping him build a do-what-it-takes-to-be-the-best image.

The dude-throws-awesome-parties criteria for hiring tends to undermine that image, as does the quid pro quo aspect of Facebook's deals with Lessin's father.

Of course, there's more at stake here than corporate vanity. Tech companies have spent a great deal of time and money trying to persuade Congress that the country must increase the number of H-1Bs we issue in order to have a viable Tech industry. Without getting into the merits of the case (for that you can check out my reply to Noah Smith on the subject), this article proves once again that one easily impressed NYT reporter is worth any number of highly paid K Street lobbyists.

The New York Times is still, for many people, the paper. I've argued before that I didn't feel the paper deserved its reputation, that you can find better journalism and better newspapers out there, but there's no denying that the paper does have a tremendous brand. People believe things they read in the New York Times. It would be nice if the paper looked at this as an obligation to live up to rather than laurels to rest on.

Segundo de Chomón and the pushbutton age

Regular readers have noticed we've been spending a lot time on the history of technology, particularly the explosive changes around the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One of the things I find most fascinating about the period is the number of concepts that are now so familiar as to be a part of our intuitive view of the world which didn't exist until the time in question.

The idea of remote control, virtually instantaneous nonmechanical action at any terrestrial distance. You touch a button, you throw switch, and lights go on, doors open, motors start. This went from being impossible to completely mundane with remarkable speed.

The pushbutton age was still fairly new when Segundo de Chomón made the groundbreaking film electric hotel. The though overshadowed by Georges Méliès, de Chomón was, for my money, probably the better filmmaker and his work with stop motion animation would prove more fertile than any of the trick effects his contemporary is remembered for.

Another piece of new technology.

No stop action, just a personal favorite.

The idea of remote control, virtually instantaneous nonmechanical action at any terrestrial distance. You touch a button, you throw switch, and lights go on, doors open, motors start. This went from being impossible to completely mundane with remarkable speed.

The pushbutton age was still fairly new when Segundo de Chomón made the groundbreaking film electric hotel. The though overshadowed by Georges Méliès, de Chomón was, for my money, probably the better filmmaker and his work with stop motion animation would prove more fertile than any of the trick effects his contemporary is remembered for.

Another piece of new technology.

No stop action, just a personal favorite.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)