[Warning, I'm pretty much shooting from the hip here. This is not an area where I am knowledgeable and I do not have the time to research the subject properly. As a result, this is very much written to the good-enough-for-blogging standard, so it would be wise to double check any of the following assertions before passing them on.]

As a general rule, I tend to be skeptical of "we need this to be competitive" arguments against regulation and antitrust enforcement. Usually these claims come down to an excuse for gouging the customer or an attempt by incompetent managers to survive by gaming the system. If you can't make a go of a business without monopoly/monopsony power, then you probably aren't very good at your job.

There are, of course, exceptions, cases where technological and economic changes really have made it difficult for even the best run companies to survive, even when those companies serve a real and necessary social good. Local journalism is a perfect case in point. Some of the best reporting I've seen over the past few years has come out of newspapers, and yes, television stations outside of the major markets of New York and LA. I particularly want to single out the TV reporters because, though we all tend to mock them, they've been responsible for some remarkably good work on stories that, though important, are often ignored by institutions like the New York Times.

John Oliver hit many of these same points in his excellent piece on Sinclair broadcasting.

.

Anything we can do to encourage more and better local journalism is worth pursuing. There are considerable synergies and cost savings from combining a newspaper and a television (and possibly even a radio) station. Furthermore, in an age of cable and the Internet, I am much less concerned with the potential abuses from having this kind of cross ownership.

The key word here (and it is absolutely essential) is "local." As soon as you start to scale up, the social benefits start to drop off while the potential for abuse increases exponentially. As the experience with Sinclair has shown us, ownership across many markets actually tends to decrease the amount of local journalism and, perhaps more importantly, the amount of local editorial control.

Put simply, the standard I have in mind is that crossownership is acceptable, perhaps even desirable, if you're talking about relatively small players in relatively constrained regions. If, on the other hand, you're talking about big players (particularly those like Sinclair with a history of stifling local journalistic autonomy), the tighter the ownership restrictions the better.

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

Monday, January 1, 2018

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Should we care that the congestion tax is regressive?

This is Joseph

Over at Vox, Matt Ygelsias very nicely hits on one of my pet peeves about people calling congestion taxes (and similarly gas taxes) regressive:

But raising revenue can be used to provide income support and social services. It is a two step process, although I can understand the confusion about this given how we seem to focus only on a "taxes are bad meme".

But Matt is completely correct that poor people don't always have cars. And if good (i.e. fast and reliable) bus service made it possible for more families to live car-free then that would be a big win, both for road safety and pollution. Or maybe safer roads make bicycles work (even greener and cheaper). Now this requires a commitment to good public transit services (or bike lanes), but I remain puzzled as to why this is remotely controversial.

I also want to note that the people making this argument seem to have no trouble with regressive taxation in other contexts. The payroll tax is more regressive than the income tax. Want to bet which one we just cut? Sales taxes are regressive, but they show no signs of being targeted in favor of an increased capital gains tax (which is progressive). I am not saying that there are not other considerations, but I always find it puzzling how regressive is brought out in this context and not any other.

I will become much more sympathetic to the "regressive" objection when it is applied more broadly. At the margin a congestion tax can finish a family financially. But so too can sales taxes, which could make the difference between sufficient and insufficient income. So if we are going to discuss regressive taxes, can we start with the elephant in the room. It's really an astonishing example of details are just not thought through. If this is the standard then I don't see regressive as a serious problem with a tax that can be a) remedied with the right spending decisions and b) has positive social consequences. So can we drop this point?

Please?

Over at Vox, Matt Ygelsias very nicely hits on one of my pet peeves about people calling congestion taxes (and similarly gas taxes) regressive:

Again and again, one hears the objection that congestion fees are regressive, but I think this is doubly mistaken. Analytically, it's true that congestion fees let the rich off relatively easy, but it's also the case that it's poor people who are disproportionately likely to not own cars and to benefit from faster buses.

But more to the point, it's easy to alter your overall tax system to make a congestion charge clearly progressive. The two main options are either to use the revenue to finance a sales tax cut (sales taxes are extremely regressive) or to pay out a "congestion dividend" to all the city's residents.I think that the current conversation about taxes has poisoned people's ability to be objective about these things. Every time there is a new source of revenue, there is a push to cut progressive taxes (like the income tax). The recent cut of the top income tax bracket is a case in point.

But raising revenue can be used to provide income support and social services. It is a two step process, although I can understand the confusion about this given how we seem to focus only on a "taxes are bad meme".

But Matt is completely correct that poor people don't always have cars. And if good (i.e. fast and reliable) bus service made it possible for more families to live car-free then that would be a big win, both for road safety and pollution. Or maybe safer roads make bicycles work (even greener and cheaper). Now this requires a commitment to good public transit services (or bike lanes), but I remain puzzled as to why this is remotely controversial.

I also want to note that the people making this argument seem to have no trouble with regressive taxation in other contexts. The payroll tax is more regressive than the income tax. Want to bet which one we just cut? Sales taxes are regressive, but they show no signs of being targeted in favor of an increased capital gains tax (which is progressive). I am not saying that there are not other considerations, but I always find it puzzling how regressive is brought out in this context and not any other.

I will become much more sympathetic to the "regressive" objection when it is applied more broadly. At the margin a congestion tax can finish a family financially. But so too can sales taxes, which could make the difference between sufficient and insufficient income. So if we are going to discuss regressive taxes, can we start with the elephant in the room. It's really an astonishing example of details are just not thought through. If this is the standard then I don't see regressive as a serious problem with a tax that can be a) remedied with the right spending decisions and b) has positive social consequences. So can we drop this point?

Please?

Friday, December 29, 2017

The Last Jedi and narrative risks *major spoilers*

This is Joseph

The last Jedi is visually amazing and has some great character moments. The plot is not the best, although that has rarely been a strength of Star Wars movies. But I did want to comment on how the plot was, in a very odd way, just as safe and conservation as the Force Awakens.

Needless to say: SPOILERS

REALLY, no kidding, SPOILERS

The Force awakens was basically the plot of a New Hope rehashed for a new group of heroes. It is not necessarily the wrong artistic choice -- bringing a series back to the basics can create a fertile ground for exploring new paths forward. Unfortunately, the Last Jedi seems to have managed to mangle the plot.

The main conceit of the new series is that they reverse expectations at every step, often just to reverse them:

The last Jedi is visually amazing and has some great character moments. The plot is not the best, although that has rarely been a strength of Star Wars movies. But I did want to comment on how the plot was, in a very odd way, just as safe and conservation as the Force Awakens.

Needless to say: SPOILERS

REALLY, no kidding, SPOILERS

The Force awakens was basically the plot of a New Hope rehashed for a new group of heroes. It is not necessarily the wrong artistic choice -- bringing a series back to the basics can create a fertile ground for exploring new paths forward. Unfortunately, the Last Jedi seems to have managed to mangle the plot.

The main conceit of the new series is that they reverse expectations at every step, often just to reverse them:

- Luke is a grumpy old man and not a wise Jedi master

- The plans that the heroes try cost lives and don't save them (Finn's expedition leads to the death of most of the surviving members of the resistance)

- Poe's reckless actions make things worse, not better, and being a hot shot ends up being counter-productive

- Snoke is killed immediately

- Turning on his master doesn't redeem Kylo Ren

- Rey falls for Kylo not Finn

- Heroic self-sacrifice is stopped by another character, with no viable plan to prevent everyone from dying

I could go on, but the trick seems to be to reverse expectations at every turn and try to make it fresh and original as a result. But what struck me is how they somehow managed to avoid all of the real narrative risks that they could have taken with the story.

And we end up with the status quo. A resistance against an empire that is overwhelmingly strong and is led by a person strong in the dark side is being led by a small group of heroes. None of the new people died. Luke becomes a force ghost, just like Yoda. The situation at the beginning is exactly like the end and we don't really have new plot angles that take us in a new and fascinating direction.

If you are going to invert expectations then you should create new paths forward. Instead we get the same set up and very little narrative payoff. Maybe that isn't the main thing in a Star Wars movie, but it definitely detracted from the otherwise very beautiful piece of film.

Robots reanimating dead musicians

From NPR (May 28, 2007)

Pianist Glenn Gould's classic 1955 recording of Bach's Goldberg Variations has never been out of print. Yet this week, Sony Classical will release a brand-new recording of it.

It’s actually a recording of a "re-performance" of the music, designed by a North Carolina software company called Zenph.

The idea is simple: Old recordings sound old. Decades of amazing musical performances are hidden behind the limits of audio technology at the time they were recorded.

The Zenph "re-performance" process isn't a remastering — that is, trying to fix an existing recording with equalization or noise reduction. Instead, it's a new recording of a performance that scientifically matches the earlier one. Zenph uses a Yamaha Disklavier Pro, an actual acoustic piano that can, with a computer's help, play back with microscopically accurate timing and sensitivity.

...

Zenph will be turning to jazz next, with a recording of “re-performances'” of Art Tatum, including a live concert performance they hope to re-create, with no one at the piano, at Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles.

Thursday, December 28, 2017

Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Merry Muskmas to all

[I've been going back and forth as to whether or not some of this is meant to be read as parody. If I missed some subtle wink from the author of the piece, pointed out in the comment section I will amend this post.]

I've been on the Elon Musk beat for quite a while now, and I thought I had a pretty good idea where the upper bound was for hype and journalistic credulity, but this Rolling Stone cover story by Neil Strauss really does set a new standard.

And that's pretty much the level of critical scrutiny you can expect from the entire piece. It's not just the lack of skepticism – – we've seen plenty of that – – but the obliviousness to the need for skepticism. Up until now, most reporters for major publications have at least acknowledged that some level of skepticism would have been appropriate. True, many of the disclaimers are little more than lip service, but the journalist on those stories understood that they should do at least the bare minimum.

Strauss is the first writer I can think of who addresses proposals like the Hyperloop completely without any mention of its critics and the serious questions about its viability.

The article even has a photo caption that reads 'Inspecting the Hyperloop, which will transport people from city to city in record time.' Not "may" or even "will probably," but "will" despite a widely held consensus among transportation and infrastructure experts that this is unlikely to be viable as anything more than a glorified amusement park ride in the foreseeable future.

We may come back to this article. There's a great deal of unintentional journalism here, insights into Musk's real and extraordinary gifts for motivation and promotion, talents that have led to some truly amazing accomplishments. There is also an interesting cautionary tale in the way Strauss lets his subject steer the narrative away from these genuinely important and impressive points and toward unquestioning acceptance of a self mythologizing narrative.

For now, though, I'm just going to let it stand with this. Frankly, reading a puff peace this inflated takes a lot out of me.

I've been on the Elon Musk beat for quite a while now, and I thought I had a pretty good idea where the upper bound was for hype and journalistic credulity, but this Rolling Stone cover story by Neil Strauss really does set a new standard.

Musk will likely be remembered as one of the most seminal figures of this millennium. Kids on all the terraformed planets of the universe will look forward to Musk Day, when they get the day off to commemorate the birth of the Earthling who single-handedly ushered in the era of space colonization.

...

“Musk is a titan, a visionary, a human-size lever pushing forward massive historical inevitabilities – the kind of person who comes around only a few times in a century”

And that's pretty much the level of critical scrutiny you can expect from the entire piece. It's not just the lack of skepticism – – we've seen plenty of that – – but the obliviousness to the need for skepticism. Up until now, most reporters for major publications have at least acknowledged that some level of skepticism would have been appropriate. True, many of the disclaimers are little more than lip service, but the journalist on those stories understood that they should do at least the bare minimum.

Strauss is the first writer I can think of who addresses proposals like the Hyperloop completely without any mention of its critics and the serious questions about its viability.

The article even has a photo caption that reads 'Inspecting the Hyperloop, which will transport people from city to city in record time.' Not "may" or even "will probably," but "will" despite a widely held consensus among transportation and infrastructure experts that this is unlikely to be viable as anything more than a glorified amusement park ride in the foreseeable future.

We may come back to this article. There's a great deal of unintentional journalism here, insights into Musk's real and extraordinary gifts for motivation and promotion, talents that have led to some truly amazing accomplishments. There is also an interesting cautionary tale in the way Strauss lets his subject steer the narrative away from these genuinely important and impressive points and toward unquestioning acceptance of a self mythologizing narrative.

For now, though, I'm just going to let it stand with this. Frankly, reading a puff peace this inflated takes a lot out of me.

Kids and Cars 2

This is Joseph

At some point I thought there was a comment on my last post asking about walking to daycare. It's actually closer than I thought in terms of time: 3.8 miles which Google maps thinks will take me 79 minutes. With a jogging stroller this would work if I only did one pick-up or drop off a day.

But I still wonder why it is such a huge deal to have daycares located near places of employment; does it make me a socialist to wonder why the extra commute works (and I am happy to pay marker rates of mid-twenty thousand per year -- it's the price of a kid).

At some point I thought there was a comment on my last post asking about walking to daycare. It's actually closer than I thought in terms of time: 3.8 miles which Google maps thinks will take me 79 minutes. With a jogging stroller this would work if I only did one pick-up or drop off a day.

But I still wonder why it is such a huge deal to have daycares located near places of employment; does it make me a socialist to wonder why the extra commute works (and I am happy to pay marker rates of mid-twenty thousand per year -- it's the price of a kid).

Tuesday, December 26, 2017

Kids and cars

This is Joseph

Duncan Black has another post up about how nice it is to live in a city, and have a lot of options to avoid driving. I lived this way for much of my life. But now I am trying to get a child into daycare. After discovering that daycares in some cities (like mine) have wait lists that are years long (not a joke), the question of why don't you get a daycare near your house rather answers itself. I am not sure why the coordination is so poor, but it makes a big difference.

So I decided to look at a commute from home to a daycare it is possible to get into (not easily) and then to work (and back). Note that these times assume normal and fast flowing traffic (ha!), which can influence both buses and cars.

Home to daycare by car: 12 minutes

Home to daycare by bus (normal morning): 34 minutes

Daycare to work by car: 14-20 minutes (google maps gives a range)

Daycare to work by bus: 37 to 44 minutes (plus time to wait for a bus)

Presuming one spends 15 minutes doing kid drop-off and that you have exactly a median wait time for the bus on the way to work (15 minutes, as they typically come every 30 minutes) plus needing to be ten minutes early for the bus in the morning (because the bus coming early is an extra 30 minute wait) then the time to do a morning drop-off and get to work:

By car: 41 to 47 minutes

By bus: 111 to 118 minutes

Now, remember that this is doubled because you need to repeat it all at the end of the day.

A car is about 50 minutes and will likely be an hour with traffic and parking. It's more expensive but it means that if I leave the house at 7 am then I can get back home at 6/6:30 pm or so, and have worked a full day, and have a buffer in case I am delayed so that I don't have to pay overtime rates at the daycare.

By bus, that's really 2 hours each way. This assumes that all of the buses come -- one bus that doesn't adds 30 minute increments. It is common at peak times of year for buses on campus to be full and not pick up any passengers. In these cases, I might have to use a taxi occasionally, which definitely makes the cost savings seem less optimal (but noting compared to late fees). If I aimed for opening of the daycare I would leave the house at 6 am, struggle to get to work at 8 am (see buses being 30 minutes apart and occasionally they get behind) and have to leave a 4 pm to make sure that I could make it all work (and not be late to daycare). No lunch break is possible and now we have a 4 to 5 hour daily commute. It's not that any leg is insane, it is that public transit needs to be exceedingly well designed to make it efficient to do a two location trip twice a day.

Now, you might ask about daycare at work. It's at least a 3 year wait list for infant care and you get routinely bumped by priority groups (making 3 years very optimistic). I guess some people are able to plan this well enough . . . or are lucky enough to not be staff.

Now, of course, an employer could make this a priority and get that waitlist dropped. But that seems so . . . alien . . . to the way that places are run these days that I struggle to see it.

But so long as daycare is a requirement (and I am not wealthy enough to have either nannies or the ability to make one salary easily work) then it's really going to drive car ownership. If you want to improve car reliance, then this seems like a very pertinent problem and a key place to start putting in some creative thinking.

Duncan Black has another post up about how nice it is to live in a city, and have a lot of options to avoid driving. I lived this way for much of my life. But now I am trying to get a child into daycare. After discovering that daycares in some cities (like mine) have wait lists that are years long (not a joke), the question of why don't you get a daycare near your house rather answers itself. I am not sure why the coordination is so poor, but it makes a big difference.

So I decided to look at a commute from home to a daycare it is possible to get into (not easily) and then to work (and back). Note that these times assume normal and fast flowing traffic (ha!), which can influence both buses and cars.

Home to daycare by car: 12 minutes

Home to daycare by bus (normal morning): 34 minutes

Daycare to work by car: 14-20 minutes (google maps gives a range)

Daycare to work by bus: 37 to 44 minutes (plus time to wait for a bus)

Presuming one spends 15 minutes doing kid drop-off and that you have exactly a median wait time for the bus on the way to work (15 minutes, as they typically come every 30 minutes) plus needing to be ten minutes early for the bus in the morning (because the bus coming early is an extra 30 minute wait) then the time to do a morning drop-off and get to work:

By car: 41 to 47 minutes

By bus: 111 to 118 minutes

Now, remember that this is doubled because you need to repeat it all at the end of the day.

A car is about 50 minutes and will likely be an hour with traffic and parking. It's more expensive but it means that if I leave the house at 7 am then I can get back home at 6/6:30 pm or so, and have worked a full day, and have a buffer in case I am delayed so that I don't have to pay overtime rates at the daycare.

By bus, that's really 2 hours each way. This assumes that all of the buses come -- one bus that doesn't adds 30 minute increments. It is common at peak times of year for buses on campus to be full and not pick up any passengers. In these cases, I might have to use a taxi occasionally, which definitely makes the cost savings seem less optimal (but noting compared to late fees). If I aimed for opening of the daycare I would leave the house at 6 am, struggle to get to work at 8 am (see buses being 30 minutes apart and occasionally they get behind) and have to leave a 4 pm to make sure that I could make it all work (and not be late to daycare). No lunch break is possible and now we have a 4 to 5 hour daily commute. It's not that any leg is insane, it is that public transit needs to be exceedingly well designed to make it efficient to do a two location trip twice a day.

Now, you might ask about daycare at work. It's at least a 3 year wait list for infant care and you get routinely bumped by priority groups (making 3 years very optimistic). I guess some people are able to plan this well enough . . . or are lucky enough to not be staff.

Now, of course, an employer could make this a priority and get that waitlist dropped. But that seems so . . . alien . . . to the way that places are run these days that I struggle to see it.

But so long as daycare is a requirement (and I am not wealthy enough to have either nannies or the ability to make one salary easily work) then it's really going to drive car ownership. If you want to improve car reliance, then this seems like a very pertinent problem and a key place to start putting in some creative thinking.

Monday, December 25, 2017

Sunday, December 24, 2017

Friday, December 22, 2017

If you've gone through the holidays without hearing "Sugar Rum Cherry"...

... you have not had a cool Christmas.

Thursday, December 21, 2017

Nine out of ten technomages recommend DNA-aligning essential oils for your essential oil needs

I've got more to say about this excellent New Yorker piece by Rachel Monroe (and about what Monroe does that other journalists should emulate). Her deep dive into the world of essential oils illuminates one of the most interesting corners of 21st century pseudo-science, the medical quackery that somehow appeals to the audiences of both Gwyneth Paltrow's Goop and Alex Jones' InfoWars.

For now now, though, I'm just going to highlight this beautiful example of magical heuristics, using the language of science to conceal fundamentally mystical thinking. [Remember to rub your screen three times clockwise before reading, unless using an Apple product, in which case it's counterclockwise.]

For now now, though, I'm just going to highlight this beautiful example of magical heuristics, using the language of science to conceal fundamentally mystical thinking. [Remember to rub your screen three times clockwise before reading, unless using an Apple product, in which case it's counterclockwise.]

Disillusioned by Western medicine, Cohen began exploring other options. She studied with multiple healers and shamans; she read books with titles like “The Body Toxic” and pursued a massage-therapy license. As part of her training, she took a class on a massage technique called “raindrop therapy,” which incorporates essential oils—aromatic compounds made from plant material. At the time, essential oils were not well known, but Cohen was drawn to them right away. “From the very first moment with those oils, I noticed something was firing that hadn’t been firing,” she said. “I was deeply moved.”

Today, Cohen puts frankincense oil on her scalp every morning; when she feels a cold coming on, she downs an immune-system-boosting oil blend that includes clove, eucalyptus, and rosemary. On days when she has to negotiate a contract on behalf of an organization that she volunteers for, she uses nutmeg and spearmint to sharpen her focus. She earns the majority of her income working as a distributor for Young Living, a leading vender of essential oils.

Cohen is middle-aged, with a friendly, open face framed by graying curls. Though her house, in Long Beach, is full of New Age trappings—a statue of Ganesh, huge hunks of crystal—she speaks with the quick clip of someone who once gave a lot of corporate presentations. As we sat at her kitchen table, a glass globe puffed out clouds of tangerine-scented vapor.

Cohen offered me a glass of water enhanced with a few drops of an essential-oil blend called Citrus Fresh. “It helps the body detox,” she said. “Not that you’re toxic.” The water was subtly tangy, like a La Croix without the fizz.

Cohen went into her treatment room and came back with a small vial labelled “Clarity.” She put a few drops in my left palm. “This is good for getting your mind clear,” she said. “Rub it clockwise three times. That activates the electrical properties in the oil, and aligns your DNA.” Following Cohen’s instructions, I cupped my hands around my nose and inhaled deeply. The smell was heavier than that of perfume, so minty that it was almost medicinal. Cohen looked at me expectantly. “I feel perkier,” I ventured.

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

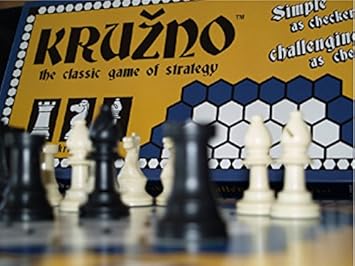

A few more words about the official game of Kružno, Slovakia*

While the gift-giving season is still upon us...

Back when I was teaching high school math, I got very much into games and puzzles as a way of teaching both specific concepts and more general skills like problem-solving and strategic thinking. In addition to all the standards (chess, checkers, etc.) and some interesting historical games, I started developing some of my own, mostly played on 6 x 6 x 6 hexagonal boards that I printed out and taped together.

I was particularly happy with the way one of these games, Kružno, turned out. It played well. The underlying dynamics were, as far as I could tell, unique, and it was what I like to call an elegant game, with very simple rules (it takes a bright seven-year-old about five minutes to catch on) supporting a reasonably high level of complexity and challenging play.

I ran off a small batch and tried my hand at selling them both individually and as part of a hexagonal game set (the 6 x 6 x 6 board can be used for dozens of contemporary and historical games). I sold a few and got some good feed back but realized I didn't have the risk-tolerance to take the business to the next level.

I've been working on an online Kružno. The logic's been worked out and I'm planning on getting it up and running next year. In the meantime, I'll keep the Amazon store up for a while longer. Check it out. I think you'll have fun with it.

* No, really.

Back when I was teaching high school math, I got very much into games and puzzles as a way of teaching both specific concepts and more general skills like problem-solving and strategic thinking. In addition to all the standards (chess, checkers, etc.) and some interesting historical games, I started developing some of my own, mostly played on 6 x 6 x 6 hexagonal boards that I printed out and taped together.

I was particularly happy with the way one of these games, Kružno, turned out. It played well. The underlying dynamics were, as far as I could tell, unique, and it was what I like to call an elegant game, with very simple rules (it takes a bright seven-year-old about five minutes to catch on) supporting a reasonably high level of complexity and challenging play.

I ran off a small batch and tried my hand at selling them both individually and as part of a hexagonal game set (the 6 x 6 x 6 board can be used for dozens of contemporary and historical games). I sold a few and got some good feed back but realized I didn't have the risk-tolerance to take the business to the next level.

I've been working on an online Kružno. The logic's been worked out and I'm planning on getting it up and running next year. In the meantime, I'll keep the Amazon store up for a while longer. Check it out. I think you'll have fun with it.

* No, really.

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

As if you didn't have enough to worry about

[This is another one of those too-topical-to-ignore topics that I don't have nearly enough time to do justice to, but I suppose that's why God invented blogging.]

There's a huge problem that people aren't talking about nearly enough. More troublingly, when it does get discussed, it is usually treated as a series of unrelated problems, much like a cocaine addict who complains about his drug problem, bankruptcy, divorce, and encounters with loan sharks, but who never makes a causal connection between the items on the list.

Think about all of the recent news stories that are about or are a result of concentration/deregulation of media power and the inevitable consequences. Obviously, net neutrality falls under this category. So does the role that Facebook, and, to a lesser extent, Twitter played in the misinformation that influenced the 2016 election. The role of the platform monopolies in the ongoing implosion of digital journalism has been widely discussed by commentators like Josh Marshall. The Time Warner/AT&T merger has gotten coverage primarily due to the ethically questionable involvement of Donald Trump, with very little being said about the numerous other concerns. Outside of a few fan boys excited over the possibility of seeing the X-Men fight the Avengers, almost no one's talking about Disney's Fox acquisition.

It didn't used to be like this. For most of the 20th century, the government kept a vigilant watch for even potential accumulation of media power. Ownership was restricted. Movie studios were forced to sell their theaters (see United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc). The largest radio network was effectively forced to split in two (that's why we have ABC broadcasting today). Media companies were tightly regulated, their workforce was heavily unionized, and they were forced to jump through all manner of hoops before expanding into new markets to insure that the public good was being served.

In short, the companies were subjected to conditions which we have been told prevent growth, stifle innovation, and kill jobs. We can never know what would've happened had the government given these companies a freer hand but we can say with certainty that for media, the Post-war era was a period of explosive growth, fantastic advances, and incredible successes both economically and culturally. It's worth noting that the biggest entertainment franchises of the market-worshiping, anything-goes 21st century were mostly created under the yoke of 20th century regulation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)