SpaceX was able to carve out a substantial niche for itself because the industry was not particularly fast-moving (and, in part, because the company acquired, or by some standards stole, a large chunk of the personnel and intellectual property from TRW).

Tesla, by comparison, is entering a free market thunder dome.

As of September 2016, series production highway-capable all-electric cars available in some countries for retail customers released to the market since 2010 include the Mitsubishi i-MiEV, Nissan Leaf, Ford Focus Electric, Tesla Model S, BMW ActiveE, Coda, Renault Fluence Z.E., Honda Fit EV, Toyota RAV4 EV, Renault Zoe, Roewe E50, Mahindra e2o, Chevrolet Spark EV, Fiat 500e, Volkswagen e-Up!, BMW i3, BMW Brilliance Zinoro 1E, Kia Soul EV, Volkswagen e-Golf, Mercedes-Benz B-Class Electric Drive, Venucia e30, BAIC E150 EV, Denza EV, Zotye Zhidou E20, BYD e5, Tesla Model X, Detroit Electric SP.01, BYD Qin EV300, and Hyundai Ioniq Electric. As of early December 2015, the Leaf, with 200,000 units sold worldwide, is the world's top-selling highway-capable all-electric car in history, followed by the Tesla Model S with global deliveries of about 100,000 units.

If you include plug-in hybrids (which I would argue that you should for now), the list becomes much longer.

The consensus in the engineering and infrastructure fields seems to be that we are not that far from the end of the age of internal combustion. I'll admit I am a bit skeptical about some of the timetables I've heard, but there is no question that we will get to the point where electric vehicles are cheaper, have better range, and can be charged in roughly the time it takes to fill up your car. When that happens, gasoline powered cars will go the way of chemical film and analog records, continuing to exist but only as a pale shadow of a once dominant technology.

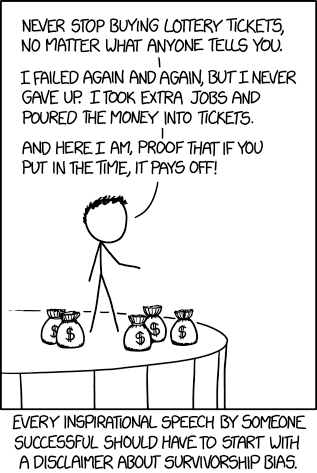

It is possible I'm missing one or two obvious exceptions, but as a rule, it is next to impossible to be wildly profitable in the presence of intense and genuine competition. If you look at companies that were basically printing money by the truckload and take out those that lucked into a quick windfall or were cooking the books, you would almost always find monopolistic pricing/rent seeking or underserved markets or some combination of the two.

It remains an open question whether or not Tesla can be a viable and consistently profitable company going forward (a sober reading of the company's recent history does not strongly support the notion), but even if the company goes on to a long and successful career as a major player in the industry, it is highly unlikely that it will ever have the kind of limited competition needed to be profitable enough to justify its market cap.

That also means it probably will never be profitable enough to justify things like this:

Meanwhile, Tesla CEO Elon Musk was just barely out of the nine-figure club, earning $99,744,920 last year, according to Bloomberg’s calculations.