This is Joseph

It looks like preexisting conditions may be back as a way to increase the costs of health insurance, and this is a bad thing. Why?

In traditional insurance, if your house burns down then the insurer makes whole the loss. In medical insurance, a major medical event may have sequels for many years. If you change insurers (or your insurer goes out of business) then the original insurer is off the hook for continuing costs. The new insurer looks at the ill participant as a "house already on fire" and would like to not cover these ongoing costs.

There is also an information issue. If a house burns down twice then that might just be bad luck. But if a person has two heart attacks, is the second one a random event or a sequel of the first one. It is pretty clear that we don't want courts adjudicating this question on a case by case basis (or people being denied care because nobody can figure this out).

The most logical solutions are regulatory (like the Affordable Care Act implemented) or structural (like implementing single payer health care). A portable system of health insurance might also work, although do you want to bet on your insurer being solvent for forty-five years?:

But there is a reason that preexisting condition clauses are unpopular. Not because people want a free lunch (although some of that may always be present) but because it opens people up to random events (employer bankruptcy, anyone) leaving them unable to afford health care.

And before anyone talks about market solutions, please try and actually use "self-pay" as an option in a modern medical setting. I actually tried this and it was very difficult to be seen by an MD (and only MDs can do things like prescribe antibiotics -- which can be life saving).

Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Friday, May 5, 2017

The Bret Stephens story is about more than climate change denial

The conversation has gotten muddled and off-topic on both sides (which is not to say that both sides are equally wrong, just that most of the critics of Bret Stephens are making a valid case badly). A great deal of the discussion has come to center around a not particularly relevant debate about whether or not certain positions are acceptable in the pages of a publication like the New York Times.

It is true that, though the exact boundaries are inevitably hazy, there are certain positions that are so innately offensive that they should have to clear and extremely high bar before making it into the public discourse. Two obvious examples are defenses of the Holocaust and slavery. There is, of course, and inherent conflict between condemning offensive ideas and defending freedom of expression, but that's not really what we should be focusing on here.

The issue here is not that Stephens took a position (or even a string of positions) that you or I strongly disagree with; the issue is that he took this string of indefensible positions (effectively taking the pro side on things like racism, torture, religious bigotry, income inequality, sexual harassment, and the war on data) and defended them by recycling tired and hackneyed arguments that are logically flawed, dishonest and/or incoherent , not to mention almost always badly written.

We are not talking about lapses in an otherwise outstanding career or bad traits that are counterbalanced by notable strengths. Bret Stephens did not succeed despite these things; his entire career was built on being an apologist hack.

Here is an illustrative example from an excellent summary compiled by Hamilton Nolan;

When you strip away all of the nonessentials, the underlying claim is that an institution or group cannot be accused of prejudice or harassment if the victims willingly choose to join. This is very closely related to the classic argument: "you don't have to be here." For a long time, this was one of the default responses to charges of discrimination. It was applied to African-Americans trying to break the color barrier, women entering traditionally male professions, gay athletes trying to be open about their sexuality, you name it.

Stephens is careful to couch his arguments in terms of some shadowy liberal conspiracy rather than an attack on victims of sexual assault, but when you claim that a woman's decision to attend an institution or pursue a profession precludes the possibility of a culture of harassment and assault, you have made this an argument about women, one that is neither sound nor original.

The New York Times knew what it was getting with their latest hire and they have been full-throated in their defense of the choice. Stephens is a tired, derivative hack of no apparent insight or talent (at least, David Brooks is good at being David Brooks). There is nothing to be learned from reading his new column, but their is a great deal to be learned from the way that America's best known "liberal" paper instinctively genuflects to the worst of American conservatism.

[Note: some typos have been corrected.]

It is true that, though the exact boundaries are inevitably hazy, there are certain positions that are so innately offensive that they should have to clear and extremely high bar before making it into the public discourse. Two obvious examples are defenses of the Holocaust and slavery. There is, of course, and inherent conflict between condemning offensive ideas and defending freedom of expression, but that's not really what we should be focusing on here.

The issue here is not that Stephens took a position (or even a string of positions) that you or I strongly disagree with; the issue is that he took this string of indefensible positions (effectively taking the pro side on things like racism, torture, religious bigotry, income inequality, sexual harassment, and the war on data) and defended them by recycling tired and hackneyed arguments that are logically flawed, dishonest and/or incoherent , not to mention almost always badly written.

We are not talking about lapses in an otherwise outstanding career or bad traits that are counterbalanced by notable strengths. Bret Stephens did not succeed despite these things; his entire career was built on being an apologist hack.

Here is an illustrative example from an excellent summary compiled by Hamilton Nolan;

The campus-rape epidemic—in which one in five female college students is said to be the victim of sexual assault—is an imaginary enemy. Never mind the debunked rape scandals at Duke and the University of Virginia, or the soon-to-be-debunked case at the heart of “The Hunting Ground,” a documentary about an alleged sexual assault at Harvard Law School. The real question is: If modern campuses were really zones of mass predation—Congo on the quad—why would intelligent young women even think of attending a coeducational school? They do because there is no epidemic. But the campus-rape narrative sustains liberal fictions of a never-ending war on women.

When you strip away all of the nonessentials, the underlying claim is that an institution or group cannot be accused of prejudice or harassment if the victims willingly choose to join. This is very closely related to the classic argument: "you don't have to be here." For a long time, this was one of the default responses to charges of discrimination. It was applied to African-Americans trying to break the color barrier, women entering traditionally male professions, gay athletes trying to be open about their sexuality, you name it.

Stephens is careful to couch his arguments in terms of some shadowy liberal conspiracy rather than an attack on victims of sexual assault, but when you claim that a woman's decision to attend an institution or pursue a profession precludes the possibility of a culture of harassment and assault, you have made this an argument about women, one that is neither sound nor original.

The New York Times knew what it was getting with their latest hire and they have been full-throated in their defense of the choice. Stephens is a tired, derivative hack of no apparent insight or talent (at least, David Brooks is good at being David Brooks). There is nothing to be learned from reading his new column, but their is a great deal to be learned from the way that America's best known "liberal" paper instinctively genuflects to the worst of American conservatism.

[Note: some typos have been corrected.]

Thursday, May 4, 2017

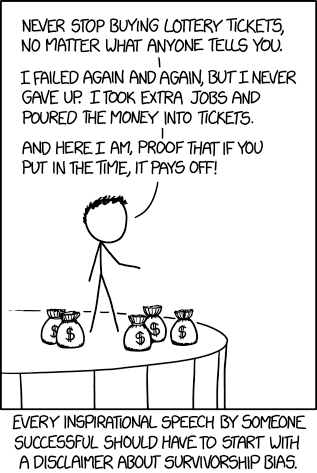

Just substitute "dropping out of college" for "buying lottery tickets" and Peter Thiel for the stick figure...

On a related note, I've been arguing for years that a winning lottery ticket is the world's best investment (though there is that one little catch).

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

PhD Vouchers

This is Joseph.

Frances Woolley asks about why we don;t have vouchers for PhD programs. As a part of this discussion she points out the issues of misalignment of incentives for K-12 school vouchers:

But the real issues are the barriers to change. These are high -- just differences in the material that is being taught can be brutal to overcome when changing mid-semester. Market forces will always be inhibited by the challenges in overcoming these barriers, especially since the service is being marketed to a proxy for the consumer.

But my biggest question is why the economist can rattle off real issues that don't even appear in the current conversation. Everything is about quality, but this all presumes that the new system (at scale) will be better than the old system. Which might be true, but pure market forces will suffer an uphill battle given transaction costs. After all, how do you prevent "we will just under-serve a little bit, but not enough to make the costs of changing schools worthwhile" becoming a "race to the bottom" for most schools (with a few high priced and elite exceptions).

Frances Woolley asks about why we don;t have vouchers for PhD programs. As a part of this discussion she points out the issues of misalignment of incentives for K-12 school vouchers:

It's odd: school vouchers are frequently advocated for primary and secondary school students. Yet there are good reasons why they would not be expected to work well, especially for primary school, as the ones exercising the vouchers (the parents) are not the ones experiencing the education (the children). Also there are very large costs associated with switching schools, and especially going to a school outside your immediate neighbourhood, if you are six years old and not able to drive, or 12 years old and in a tight friend network. Hence the possibility for effective competition between schools is limited at the K to 12 level.I think a lot of the same issues would apply to PhD vouchers as would apply to school vouchers, especially in terms of the issues of coordination. So I am not a fan of the PhD vouchers idea, doubly so when there are provincial funding differences for the schools themselves. I can see too many ways that we could end up with all viable students being at the University of Toronto, for example, with a clever use of network effects.

But the real issues are the barriers to change. These are high -- just differences in the material that is being taught can be brutal to overcome when changing mid-semester. Market forces will always be inhibited by the challenges in overcoming these barriers, especially since the service is being marketed to a proxy for the consumer.

But my biggest question is why the economist can rattle off real issues that don't even appear in the current conversation. Everything is about quality, but this all presumes that the new system (at scale) will be better than the old system. Which might be true, but pure market forces will suffer an uphill battle given transaction costs. After all, how do you prevent "we will just under-serve a little bit, but not enough to make the costs of changing schools worthwhile" becoming a "race to the bottom" for most schools (with a few high priced and elite exceptions).

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

ESPN and the content bubble

It is easy to forget that, though it does occupy a unique niche, sports is part of the entertainment economy.

For years now, we have been discussing the increasingly apparent content bubble. Even though people's ability to consume content is approaching saturation (even taking into account multiple screens) and the competing sources of content are exploding, prices and production slates continue to skyrocket. This is not to say that there isn't a lot of money to be made or that the amount will not continue to grow, just that the probable rate of growth is nowhere near what would be needed to justify the current level of investment and hype.

We have mainly focused the discussion on things like scripted television and streaming services, but the recent news from the cable sports industry might provide a better example:

For years now, we have been discussing the increasingly apparent content bubble. Even though people's ability to consume content is approaching saturation (even taking into account multiple screens) and the competing sources of content are exploding, prices and production slates continue to skyrocket. This is not to say that there isn't a lot of money to be made or that the amount will not continue to grow, just that the probable rate of growth is nowhere near what would be needed to justify the current level of investment and hype.

We have mainly focused the discussion on things like scripted television and streaming services, but the recent news from the cable sports industry might provide a better example:

ESPN's Diminished Future Has Become Its Present by Kevin Draper

The causes of the layoffs are clear. As ESPN’s subscriber base, and the rate those subscribers paid monthly, grew in the late aughts and early 2010s, Bristol spent flagrantly. They created the Longhorn and SEC Networks, built a massive new SportsCenter studio, hired hundreds of writers to cover specific teams, and, most importantly, spent billions of dollars on live sports rights. They made big bets. They made wrong bets.

Right around the time the ink dried on a $15.2 billion deal to broadcast the NFL, subscribers began fleeing cable television in droves—not because of anything the Worldwide Leader did wrong, but because of secular changes in the way broadcast and video works. Phones, Twitter, and YouTube began instantaneously delivering highlights and entire games to fans, obviating the need for anyone to watch SportsCenter, or any other news shows, to catch up on what happened in sports, or even, in some cases, to watch live games. Terrestrial ad revenue never migrated online, and the revenue to be found there was largely eaten up by Facebook and Google, leaving little to pay those new ESPN.com reporters.

ESPN is still wildly profitable—the operating income of Disney’s media networks (of which ESPN plays the largest role) was $1.36 billion in the 2016 fourth quarter—but it’s less profitable than it used to be, and projects to be far less so in the future. With its latest cuts, ESPN isn’t just trying to stanch the bleeding and/or to be seen by investors as attempting to do so: They’re also laying out what the network will look like over the next five years and beyond.

…

If ESPN is trying to significantly trim costs, things are going to get grim, because cutting the salaries of online writers isn’t going to cut it. And so the fundamental question is how long ESPN—or Disney, or Disney shareholders—can be content with diminishing profits, and at what point they admit that aggressively outbidding competitors for live rights at the peak of what was at the time clearly a bubble was a mistake. If they do so, the knock-on effect to the leagues that rely upon their money to pay salaries and fund operations will be immense.

Monday, May 1, 2017

No-excuse charters and collateral damage

From Valerie Strauss writing for the Washington Post:

One of the points some of us have been raising for years now is that movement reformers lack adequate concern about the collateral damage of their proposals. It isn't just that many of the schools that reformers hold up as models have disturbingly high attrition rates; it is that (as both a motivational and a PR tool) these programs build themselves up as students' best and even sometimes last hope for escaping poverty and having a good professional life.

To say that this gets families' hopes up is a grotesque understatement, but arguably even worse, the kids who are unable to make it into the programs or complete them are essentially told that they are doomed to failure. Between the emotional damage, the disruption and the danger of a costly self-fulfilling prophesy, that is a hell of a toll to inflict on already disadvantaged kids.

“College or Die.”

That’s the motto of the Charles A. Tindley Accelerated School, a charter school in Indiana which, according to its website, “expects 100% of its students to be accepted at a fully-accredited four-year college or university” and “to achieve exceptionally high levels of scholarship and citizenship.”

The words “College or Die” are posted in giant letters in a hallway of Tindley, an open-enrollment charter school for grades six through 12 that opened in 2004 in a former grocery store in a low-income area of Indianapolis. It became well known in school reform circles when it was visited in 2011 by then-Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels (R) and then-U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, who heaped lavish praise on the school for its success in getting students into college.

...

Here’s what it doesn’t say: A lot of students leave the school before they get to senior year. Here’s an enrollment chart from the Indiana Department of Education:

As noted by educator and blogger Gary Rubinstein, Tindley had 93 students in ninth grade in 2013-2014. By the time that cohort got to 12th grade, only 40 students were in the class. That’s a loss of 57 percent. Such a big rate of attrition is not exclusive to Tindley; a number of charter schools, especially of the “no excuses” variety, lose a lot of students and don’t replace them. Students who can’t cut it have to find another school to take them, sometimes in the middle of a school year.

One of the points some of us have been raising for years now is that movement reformers lack adequate concern about the collateral damage of their proposals. It isn't just that many of the schools that reformers hold up as models have disturbingly high attrition rates; it is that (as both a motivational and a PR tool) these programs build themselves up as students' best and even sometimes last hope for escaping poverty and having a good professional life.

To say that this gets families' hopes up is a grotesque understatement, but arguably even worse, the kids who are unable to make it into the programs or complete them are essentially told that they are doomed to failure. Between the emotional damage, the disruption and the danger of a costly self-fulfilling prophesy, that is a hell of a toll to inflict on already disadvantaged kids.

Friday, April 28, 2017

That's right, a Rube Goldberg machine as narrative medium

From Gizmodo's Andrew Liszewski:

Biisuke Ball’s Big Adventure is actually a sequel to an earlier Rube Goldberg machine featuring the adventures of Biisuke, Biita, and Biigoro, three colored balls who somehow have more personality than most action stars. This adventure, which involves sneaking through camps and foiling traps, only plays out for about three-and-a-half minutes, but if Hollywood is reading this, we’d gladly sit through two hours of this in a movie theater.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

All of the great ones make sacrifices

I'm planning to come back and connect this to some larger points, but for now I decided to get a quick post in to beat the Gizmodo rush.

From CNBC [emphasis added]:

From CNBC [emphasis added]:

In fact, a crucial decision Elon Musk was forced to make in 2010 when, by his own account, the billionaire was broke, is one of the reasons Musk has been able to cash in on Tesla's rapid share rise this year: Musk held on to shares at the very moment when a sale to raise cash would have made financial sense.

Musk, who had $200 million in cash at one point, invested "his last cent in his businesses" and said in a 2010 divorce proceeding, "About four months ago, I ran out of cash." Musk told the New York Times' DealBook at that time, "I could have either done a rushed private stock sale or borrowed money from friends."

It's a dilemma that many entrepreneurs face, but there is a big difference between the options available to Musk and the options available to most business owners. Musk was able to live on $200,000 a month in loans from billionaire friends — while still flying in a private jet — rather than sell any of his Tesla stake. Though the root of the problem is the same: intangible assets or, in other words, a business owner who is "asset rich" and "cash poor." And it can lead business owners to the most difficult decision of all: having to sell a piece or even all of their company.

Singapore Health Care Costs

This is Joseph

Ezra Klein has a very good Vox article on US versus Singaporean health care systems in terms of health care cost control. The real crux of the issue is here:

According to the World Bank, in 2014 Singapore spent $2,752 per person on health care. America spent $9,403. Given this, it’s worth asking a few questions about what Singapore’s model really has to teach the US.The key issue that Mr. Klein's article rests on is that people in Singapore are wealthier than Americans. So you can make some pretty good inferences about their health care costs being translated to the United States, as it avoids the issue of whether or not we spend more on health care because we have more to spend. Americans spend 3.4 times as much on health care as Singapore which means the funding instruments that Singapore uses would need to be scaled up.

Are Singaporeans really more exposed to health costs than Americans? The basic argument for the Singaporean system is that Singaporeans, through Medisave and the deductibles in Medishield, pay more of the cost of their care, and so hold costs down. Americans, by contrast, have their care paid for by insurers and employers and the government, and so they have little incentive to act like shoppers and push back on prices. But is that actually true?

I doubt it. The chasm in total spending is the first problem. Health care prices are so much lower in Singapore that Singaporeans would have to pay for three times more of their care to feel as much total expense as Americans do. Given the growing size of deductibles and copays in the US, I doubt that’s true now, if it ever was. (It’s worth noting that, on average, Singaporeans are richer than Americans, so the issue here is not that we have more money to blow on health care.)

According to Singapore’s data, in 2008 cash and Medisave financed a bit less than half of the system’s total costs. Let’s say, generously, that’s $1,200 in annual spending. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the average deductible in employer health plans is now $1,478 — and that’s to say nothing of premiums, copays, etc. And of course, average deductibles outside the employer market are much, much higher.

So Medisave (between 7 and 9.5% of income) would translate to 24 to 32% of income (maybe more as Americans are poorer so there would still likely be shortfall), and then you would have to pay Medishield premiums (hard to imagine these are less than 10% if they also have to be 3.4 times as large). This is before payroll taxes (say 15%), income taxes and sales taxes, in terms of the total government mandated spending and taxation. This seems very high and would immediately make the United States a very high tax country (remember Medisave is a government mandate).

The other amazing point in the passage above is that deductibles in the US now exceed total costs in Singapore (by a fair bit). This gives absolutely no evidence that increasing the amount of "skin in the game" is going to accomplish anything like a transition to a lower cost system (if the cost to consumers is what matters we already exceed what Singapore spends, and our costs do not appear to be rapidly declining). We have talked before about how the health care system resists patients bargain shopping (or even identifying real costs in advance) and has a monopoly on many services (like pharmaceutical medications).

If we want to reduce costs then we really need new ideas (government regulation?). Because just passing costs to the consumer isn't doing much to reduce total costs, relative to other health care systems. This is not to say that there is nothing to be done, but that increasing costs to consumers increases suffering and is having little effect. Perhaps the redesign of the ACA (AHCA), as it continues to undergo revision, should grapple with creative ways to improve the affordability of health care in the United States.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

More on the possible WGA strike

[Thanks to the scheduling function, my posts can be out of date before they even show up.]

Ken Levine has another interesting and somewhat counterintuitive piece on the possible upcoming writers strike.

One of the strange dynamics of labor politics in general and of this story in particular is the asymmetry of organization and homogeneity. As Levine has noted previously, when we say "producers," we are not talking about the names you see at the end of your favorite TV series. We are mainly talking about the major studios. That means on the management side you have a handful of similar players with similar interests.

On the other side you have a large and remarkably diverse group of writers. In terms of career and economic interests, they range from well-established names at the top of the heap to journeymen who work semi-regularly and support themselves to part-timers (often hyphenated actors, writers and producers) and newbies who are just breaking in. As a result, the impact of a strike varies greatly from segment to segment.

Of course, in labor negotiations, the reality of solidarity is often less important than the perception...

Ken Levine has another interesting and somewhat counterintuitive piece on the possible upcoming writers strike.

One of the strange dynamics of labor politics in general and of this story in particular is the asymmetry of organization and homogeneity. As Levine has noted previously, when we say "producers," we are not talking about the names you see at the end of your favorite TV series. We are mainly talking about the major studios. That means on the management side you have a handful of similar players with similar interests.

On the other side you have a large and remarkably diverse group of writers. In terms of career and economic interests, they range from well-established names at the top of the heap to journeymen who work semi-regularly and support themselves to part-timers (often hyphenated actors, writers and producers) and newbies who are just breaking in. As a result, the impact of a strike varies greatly from segment to segment.

Of course, in labor negotiations, the reality of solidarity is often less important than the perception...

I know it sounds strange, but the best way for WGA members to AVOID a strike is to vote YES to authorize it.

Huh? you may be saying.

Here's why: Management is just waiting to see how committed the WGA is to strike. If the Guild sends a resounding message that it is solidly behind our negotiating committee the producers will be way more willing to hammer out a deal and be done with it. They don't really want a strike either. They're making $51 billion in profit a year -- why throw a monkey wrench into that?

If however, the Guild does not give Strike Authorization, or even tepid support, then the producers will let us go on strike, let us suffer, and then give us nothing -- knowing the membership is apt to cave. The worst of both worlds.

Monday, April 24, 2017

A duopoly never provides “sufficient competition”

As follow-up to our earlier post on the inability of market forces to fix airlines, Gizmodo's Libby Watson opens up her evisceration of the current head of the FCC with a great example of someone who doesn't understand how competition and free markets work.

The Federal Communications Commission voted today to eliminate price caps on broadband services for businesses, schools, libraries, and hospitals, known as Business Data Services (BDS). The argument advanced by FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai, and the big telecoms who wanted this rule repealed, was that there is already “sufficient competition” in this market, and these price caps were getting in the way of the beautiful free market doing its thing. (As Motherboard noted, the Obama-era FCC pointed to research showing that 97 percent of BDS locations are served by just two providers, which doesn’t sound a lot like sufficient competition.) Without price caps and competition, incumbent providers can charge as much as they want to schools and libraries, who of course have been getting a free ride on providing internet to children for too long. Even freedom-loving Republicans like Sen. Tom Cotton asked the FCC to slow their roll on this proposal.

Friday, April 21, 2017

I love this helicopter

Michael Ballaban writing for the Gawker remnant Jalopnik:

The K-Max actually went through an initial production run from 1991 to 2003, and the main reason for the weird rotor configuration is that there’s no need for a tail rotor, which saps power that could instead be used for generating vertical lift. Having two main rotors which spin in opposite directions cancels out the need for a tail rotor to push against the torque of one big main rotor, much like you’d see on another heavy-lifting helicopter, the CH-47 Chinook.

But the Chinook isn’t designed specifically as a heavy lifting machine. It’s a huge, multi-purpose helicopter designed for a variety of missions, which helps explain its fore-and aft rotor layout. The K-Max, on the other hand, is designed specifically to carry loads slung underneath it via a long cable, and that necessitates it being small, narrow, and, well, weird,

Thursday, April 20, 2017

"Southwest, where we beat the competition, not the customers."

[Part of a flight attendant's closing announcement Thursday]

Just to review:

As many people have pointed out, United could easily have avoided all this if they hadn't arbitrarily capped their offer at $800, a fairly low ceiling given the potential inconvenience for the travelers. We often hear libertarian pundits and freshwater economists arguing that we could take care of all of air travels problems with less regulation and more airports, but when an industry reaches the point where it avoids obvious market-based solutions, expecting that industry to be fixed by more market-based solutions is naïve bordering on delusional.

Markets can be exceptionally powerful and effective tools for aligning incentives and allocating resources, but they are not magic. The people who think that they are should be granted no more respect or attention then is given to people who believed in any other kind of magic.

The auto industry makes a useful point of comparison here. Relative to the airline industry, it is more responsive, innovative, and customer focused. This is because the conditions necessary for having a well functioning and efficient market are much better met.

We have vigorous international competition. True, this is slightly undercut by the way we license dealerships, but the overall result is still far better than the airlines could ever hope to achieve. Furthermore, there are few principal agent problems (unlike the case with business air travel). The pricing is more opaque than it should be, but nothing like the roulette wheel of buying an airline ticket.

And there is one other factor that is extremely important but which seldom gets mentioned: the car buying process is relatively unconstrained. There is usually a great deal of flexibility as to when and where you can buy a car. That ability to walk away shifts considerable power back to the consumer and makes for more informed and rational decisions.

None of this is meant to hold up the automobile industry as a model of perfect capitalism. There is a great deal of room for improvement, but at least it makes sense to talk about automobiles in these econ 101 terms. Airlines aren't even close. With the possible exception of a handful of very large markets such as Los Angeles/Orange, you will never be able to get enough airlines, flights, and airports to achieve the necessary critical mass of options and competition. No one has proposed a level of expansion that would give most Americans a range of choices whenever and where ever they need to go, which means talk of market-based solutions is premature at best.

Just to review:

On Sunday, a man was forcibly dragged off a United flight headed from Chicago to Louisville after he refused to give up his seat to a United employee who “needed to be in Louisville” for a flight the following day, The Courier-Journal reports.

Passenger Audra Bridges, who uploaded a video of the incident to Facebook, told the newspaper that United initially offered customers $400 and a hotel room if they offered to take a flight the next day at 3pm. Nobody chose to give up the seat that they paid for, so United upped the ante to $800 after passengers boarded, announcing that the flight would not leave until four stand-by United employees had seats. After there were still no takers, a manager allegedly told passengers that a computer would select four passengers to be kicked off the flight.

As many people have pointed out, United could easily have avoided all this if they hadn't arbitrarily capped their offer at $800, a fairly low ceiling given the potential inconvenience for the travelers. We often hear libertarian pundits and freshwater economists arguing that we could take care of all of air travels problems with less regulation and more airports, but when an industry reaches the point where it avoids obvious market-based solutions, expecting that industry to be fixed by more market-based solutions is naïve bordering on delusional.

Markets can be exceptionally powerful and effective tools for aligning incentives and allocating resources, but they are not magic. The people who think that they are should be granted no more respect or attention then is given to people who believed in any other kind of magic.

The auto industry makes a useful point of comparison here. Relative to the airline industry, it is more responsive, innovative, and customer focused. This is because the conditions necessary for having a well functioning and efficient market are much better met.

We have vigorous international competition. True, this is slightly undercut by the way we license dealerships, but the overall result is still far better than the airlines could ever hope to achieve. Furthermore, there are few principal agent problems (unlike the case with business air travel). The pricing is more opaque than it should be, but nothing like the roulette wheel of buying an airline ticket.

And there is one other factor that is extremely important but which seldom gets mentioned: the car buying process is relatively unconstrained. There is usually a great deal of flexibility as to when and where you can buy a car. That ability to walk away shifts considerable power back to the consumer and makes for more informed and rational decisions.

None of this is meant to hold up the automobile industry as a model of perfect capitalism. There is a great deal of room for improvement, but at least it makes sense to talk about automobiles in these econ 101 terms. Airlines aren't even close. With the possible exception of a handful of very large markets such as Los Angeles/Orange, you will never be able to get enough airlines, flights, and airports to achieve the necessary critical mass of options and competition. No one has proposed a level of expansion that would give most Americans a range of choices whenever and where ever they need to go, which means talk of market-based solutions is premature at best.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

“Special Ed School Vouchers May Come With Hidden Costs”

With the hiring of Dana Goldstein, the New York Times has definitely upped its game in education coverage.

For many parents with disabled children in public school systems, the lure of the private school voucher is strong.

Vouchers for special needs students have been endorsed by the Trump administration, and they are often heavily promoted by state education departments and by private schools, which rely on them for tuition dollars. So for families that feel as if they are sinking amid academic struggles and behavioral meltdowns, they may seem like a life raft. And often they are.

But there’s a catch. By accepting the vouchers, families may be unknowingly giving up their rights to the very help they were hoping to gain. The government is still footing the bill, but when students use vouchers to get into private school, they lose most of the protections of the federal Individuals With Disabilities Education Act.

Many parents, among them Tamiko Walker, learn this the hard way. Only after her son, who has a speech and language disability, got a scholarship from the John M. McKay voucher program in Florida did she learn that he had forfeited most of his rights.

“Once you take those McKay funds and you go to a private school, you’re no longer covered under IDEA — and I don’t understand why,” Ms. Walker said.

In the meantime, public schools and states are able to transfer out children who put a big drain on their budgets, while some private schools end up with students they are not equipped to handle, sometimes asking them to leave. And none of this is against the rules.

“The private schools are not breaking the law,” said Julie Weatherly, a special-education lawyer who consults for school districts in Florida and other states. “The law provides no accountability measures.”

McKay is the largest of 10 such disability scholarship programs across the country. It serves over 30,000 children who have special needs. At the Senate confirmation hearing for Betsy DeVos, President Trump’s education secretary, she cited research from the conservative Manhattan Institute, saying that “93 percent of the parents utilizing that voucher are very, very pleased with it.”

Legal experts say parents who use the vouchers are largely unaware that by participating in programs like McKay, they are waiving most of their children’s rights under IDEA, the landmark 1975 federal civil rights law. Depending on the voucher program, the rights being waived can include the right to a free education; the right to the same level of special-education services that a child would be eligible for in a public school; the right to a state-certified or college-educated teacher; and the right to a hearing to dispute disciplinary action against a child.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)