Check

here to get up to speed on the discussion.

At least for me, big posts tend to bring a lot of little posts in their wake. In the course of fact checking and looking up background, interesting facts pop up that make for brief, freestanding posts. Since these are quick to write, they usually get posted before the piece that inspired them (thus somewhat mixing the wake metaphor). Sometimes the big posts never get finished, leaving the smaller ones with something of a non sequitur quality.

In the case of the recent bike share thread, the main topic I wanted to address was the way New York City's bike share program has been covered (particularly the environmental aspect) and how that coverage compares to other recent environmental stories.

Citi Bike has turned into a major national story. Here are some of the reasons I think it does not merit that level of attention:

More bicycles are not going to be a big part of the solution to our environmental and transportation problems. This is a cheap, reliable, and well-established technology that everybody knows about. As a result, most of the benefits of the technology have been realized. We can, of course, get still more by making cities more bike-friendly and bikes cheaper and more convenient, but there's not a lot of low hanging fruit here, particularly when compared to steps like fixing rail choke points and shifting over to more plug in hybrids and electric vehicles;

Bike share programs can only play a limited role in promoting cycling. Bikes are already cheap and easily stored and transported, thus limiting the incremental value. Furthermore, sharing programs work best in the same high density areas where public transportation is generally most plentiful;

The New York City example is likely to have little impact on the future of bike share programs. We're talking about an extraordinarily unrepresentative place, expensive, densely populated, compact with so little available space that even bike parking is an issue, and served by an exceptional public transportation system. It's going to be difficult to widely generalize from that experience.

This is not to say that the NYC program and ride sharing in general aren't admirable and worthwhile programs -- give me an initiative, I'll vote for it -- but they remain a small part of a small part of the solution.

By comparison, a major international reduction in the use of coal might well be the most important thing we can do to address global warming and ocean acidification. It is also a story with huge economic implications and a long list of winners and losers.

By any reasonable standard, the Obama administration's

recent proposed policy changes surrounding coal are a couple of orders of journalistic magnitude bigger than a bike share program in a single city, but that certainly doesn't seem to be reflected in the levels of coverage we've seen.

As an admittedly crude way of attaching some numbers to this I did the following Google news searches and noted the number of hits I got for certain phrases (no quotes). The actual numbers jumped around but the first position seems to remain the same

new york city bike share

About 65,000 results

obama climate change speech

About 57,500 results

obama climate change coal

41,700 results

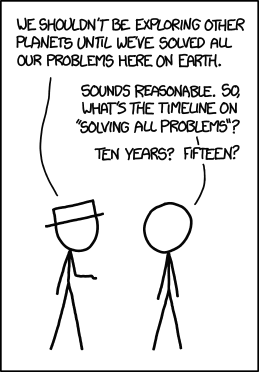

I take a couple of things away from this. the first is the way that the culture of journalism affects what we see and read. The second is our ability to have the kind of discussion needed to solve big problems.

I've been making the point for a while now that the press corps has a problem with homogeneity and insularity. If you look at truly influential journalists and opinion makers, you will see certain groups highly over-represented (such as New Yorkers). It's only natural that stories which affect those groups tend to get noticed. What's less excusable is the apparent lack of awareness on the subject. There's nothing wrong with being an upper-middle to upper class, ivy-league educated professional who lives and/or works in NYC or DC. The is something wrong with assuming that most people share those circumstances, particularly if part of your job is providing a balanced account of things. The NYC bike share program has a disproportionate effect on important members of the press corps so it's not surprising that it receives disproportionate coverage. A similar dynamic tends to amplify the coverage of high end electronics and dampen coverage of items predominantly used by the lower-middle and lower classes like over the air TV (though that demographic is changing).

But the far bigger issue is our apparent inability to maintain the sense of prospective necessary for the kind of prioritized discussions that lead to solutions of big problems. I'm not saying there's no room for smaller matters but there needs to be some sense of proportionality. Important issues like coal policy, ocean acidification, CAFE standards and the future of nuclear power are often pushed to the back pages. Others, like

rail choke points, receive almost no attention at all.

Obviously public discourse is not a zero sum game. The time we spend talking about bike sharing doesn't have to come out of the time we would have spent talking about fuel efficiency, but there are limits to our bandwidth and until we start giving appropriate attention to environmental issues, we simply won't have time for the small stuff.

.jpg)