Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Back when fifty years was a long time ago

I've noticed over the past year or two that people ranging from Neal Stephenson to Paul Krugman have been increasingly open about the possibility that technological progress been under-performing lately (Tyler Cowen has also been making similar points for a while). David Graeber does perhaps the bst job summing up the position (though I could do without the title).

The case that recent progress has been anemic is often backed with comparisons to the advances of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries (for example). There are all sorts of technological and economic metrics that show the extent of these advances but you can also get some interesting insights looking at the way pop culture portrayed these changes.

Though much has been written pop culture attitudes toward technological change, almost all focus on forward-looking attitudes (what people thought the future would be like). This is problematic since science fiction authors routinely mix the serious with the fanciful, satiric and even the deliberately absurd. You may well get a better read by looking at how people in the middle of the Twentieth Century looked at their own recent progress.

In the middle of the century, particularly in the Forties, there was a great fascination with the Gay Nineties. It was a period in living memory and yet in many ways it seemed incredibly distant, socially, politically, economically, artistically and most of all, technologically. In 1945, much, if not most day-to-day life depended on devices and media that were either relatively new in 1890 or were yet to be invented. Even relatively old tech like newspapers were radically different, employing advances in printing and photography and filled with Twentieth Century innovations like comic strips.

The Nineties genre was built around the audiences' self-awareness of how rapidly their world had changed and was changing. The world of these films was pleasantly alien, separated from the viewers by cataclysmic changes.

The comparison to Mad Men is useful. We have seen an uptick in interest in the world of fifty years ago but it's much smaller than the mid-Twentieth Century fascination with the Nineties and, more importantly, shows like Mad Men, Pan Am and the Playboy Club focused almost entirely on social mores. None of them had the sense of travelling to an alien place that you often get from Gay Nineties stories.

There was even a subgenre built around that idea, travelling literally or figuratively to the world of the Nineties. Literal travel could be via magic or even less convincing devices.

(technically 1961 is a little late for this discussion, but you get the idea)

Figurative travel involved going to towns that had for some reason abandoned the Twentieth Century. Here's a representative 1946 example from Golden Age artist Klaus Nordling:

There are numerous other comics examples from the Forties, including this from one of the true geniuses of the medium, Jack Cole.

More on Glaeser and Houston

From the comment section to my recent post on Edward Glaeser (from a reader who was NOT happy with my piece), here's a quote from Glaeser that does put Houston where it belongs:

Harris 2,367/sq mi

Westchester 2,193/sq mi

But Harris does include Houston. None of the counties that contain parts of NYC have a density lower than Harris (not even close). Of course, the county to county comparisons are problematic, but we get the same results from the much cleaner city-to-city comparison.

Houston 3,623/sq mi

New York City 27,012.5/sq mi

We could go back and forth on the best way to slice this data, but this is a big difference to get around. This doesn't mean that population density is driving the difference in housing between New York and Houston or regulation isn't the main driver here.

But the Harris/Westchester example Glaeser used to prove his point was badly chosen and it's worrisome that neither he, the New York Times or the vast majority of the blogosphere picked up on that.

If our Houston family's income is lower, however, its housing costs are much lower. In 2006, residents of Harris County, the 4-million-person area that includes Houston, told the census that the average owner-occupied housing unit was worth $126,000. Residents valued about 80% of the homes in the county at less than $200,000. The National Association of Realtors gives $150,000 as the median price of recent Houston home sales; though NAR figures don't always accurately reflect average home prices, they do capture the prices of newer, often higher-quality, housing.Just to review, I had criticized Glaeser for this quote:

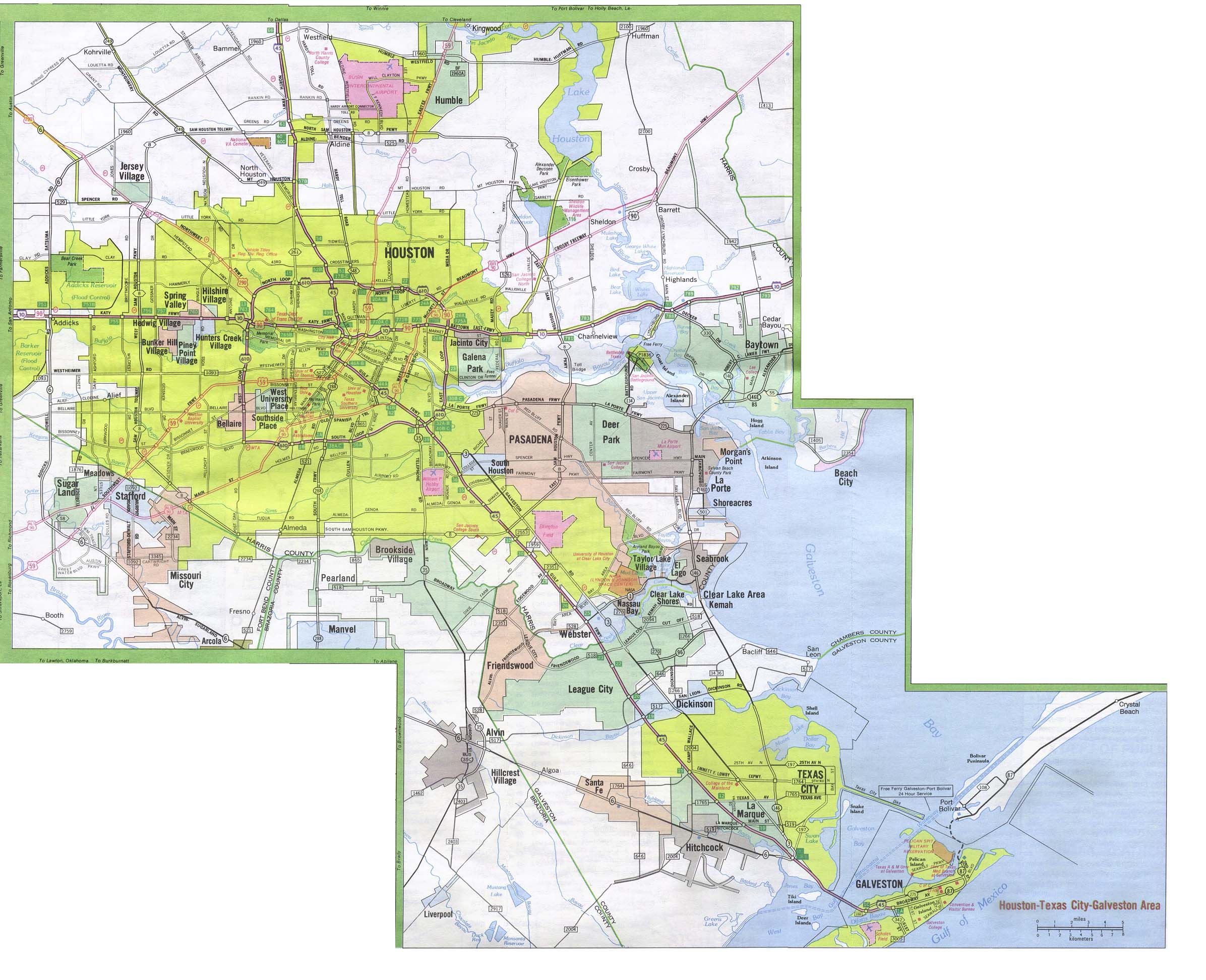

Why is housing supply so generous in Georgia and Texas? It isn’t land. Harris County, Tex., which surrounds Houston, has a higher population density than Westchester County, N.Y.So should we write off the "surrounds" as a bad choice of words and move on to another topic? Not quite yet. The trouble is that the placement of Houston doesn't just shift; it shifts in a way that's necessary for Glaeser's argument to work. If Houston weren't in Harris then the Westchester comparison would make sense. Here are the population densities (all numbers courtesy of Wikipedia)

Harris 2,367/sq mi

Westchester 2,193/sq mi

But Harris does include Houston. None of the counties that contain parts of NYC have a density lower than Harris (not even close). Of course, the county to county comparisons are problematic, but we get the same results from the much cleaner city-to-city comparison.

Houston 3,623/sq mi

New York City 27,012.5/sq mi

We could go back and forth on the best way to slice this data, but this is a big difference to get around. This doesn't mean that population density is driving the difference in housing between New York and Houston or regulation isn't the main driver here.

But the Harris/Westchester example Glaeser used to prove his point was badly chosen and it's worrisome that neither he, the New York Times or the vast majority of the blogosphere picked up on that.

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Glaeser... Glaeser... Where have I heard that name before?

Joseph's last post has got me thinking that it might be a good time for a quick Edward Glaeser retrospective.

Glaeser is, unquestionably, a smart guy with a lot of interesting ideas. Unfortunately, those ideas come with a heavy dose of confirmation bias, a bias made worse by a strong tendency to see the world through a conservative/libertarian filter, a provincial attitude toward much of the country and a less than diligent approach to data. The result is often some truly bizarre bits of punditry.

The provincialism and cavalier approach are notably on display in this piece of analysis involving Houston, a city Glaeser has written about extensively.

Keep in mind that Glaeser is one of the leading authorities on cities and Houston is one of his favorite examples.

[Update: Glaeser has correctly placed Houston is Harris County in the past, though the Harris/Westchester comparison still raises questions.]

Glaeser's flawed example was part of a larger argument that "Red State growth is that Republican states have grown more quickly because building is easier in those states, primarily because of housing regulations. Republican states are less prone to restrict construction than places like California and Massachusetts, and as a result, high-quality housing is much cheaper."

Like so much of Glaeser, it's an interesting idea with some important implications but as presented it doesn't really fit the data.

This confirmation bias can lead to some other truly strange examples:

Glaeser's confirmation bias has led him to make a number of other easily refuted arguments. His predictions about the auto bailout aren't looking good. Joseph pointed out numerous problems with his statements about food stamps. Dominik Lukeš demolished his school/restaurant analogy. His claims about Spain's meltdown are simply factually wrong.

To make matters worse, Glaeser doesn't seem to show much interest in engaging his critics. As far as I know, none of these points have ever been addressed.

Glaeser is, unquestionably, a smart guy with a lot of interesting ideas. Unfortunately, those ideas come with a heavy dose of confirmation bias, a bias made worse by a strong tendency to see the world through a conservative/libertarian filter, a provincial attitude toward much of the country and a less than diligent approach to data. The result is often some truly bizarre bits of punditry.

The provincialism and cavalier approach are notably on display in this piece of analysis involving Houston, a city Glaeser has written about extensively.

Why is housing supply so generous in Georgia and Texas? It isn’t land. Harris County, Tex., which surrounds Houston, has a higher population density than Westchester County, N.Y.The trouble is Houston is IN Harris County (technically, the town does spill over into a couple of other counties -- Texas counties are on the small side -- but it's mainly Harris).

Keep in mind that Glaeser is one of the leading authorities on cities and Houston is one of his favorite examples.

[Update: Glaeser has correctly placed Houston is Harris County in the past, though the Harris/Westchester comparison still raises questions.]

Glaeser's flawed example was part of a larger argument that "Red State growth is that Republican states have grown more quickly because building is easier in those states, primarily because of housing regulations. Republican states are less prone to restrict construction than places like California and Massachusetts, and as a result, high-quality housing is much cheaper."

Like so much of Glaeser, it's an interesting idea with some important implications but as presented it doesn't really fit the data.

This confirmation bias can lead to some other truly strange examples:

But there was a crucial difference between Seattle and Detroit. Unlike Ford and General Motors, Boeing employed highly educated workers. Almost since its inception, Seattle has been committed to education and has benefited from the University of Washington, which is based there. Skills are the source of Seattle’s strength.The University of Michigan is essentially in a suburb of Detroit. UM and UW are both major schools with similar standings. Washington is better in some areas, Michigan is better in others, but overall they are remarkably close. When you add in Wayne State (another fine school), the argument that Seattle is doing better than Detroit because of the respective quality of their universities is, well, strange.

Glaeser's confirmation bias has led him to make a number of other easily refuted arguments. His predictions about the auto bailout aren't looking good. Joseph pointed out numerous problems with his statements about food stamps. Dominik Lukeš demolished his school/restaurant analogy. His claims about Spain's meltdown are simply factually wrong.

To make matters worse, Glaeser doesn't seem to show much interest in engaging his critics. As far as I know, none of these points have ever been addressed.

Friday, December 28, 2012

Disability and work

Via Brad Delong we have this quote from Eschaton:

and

The real issue is unemployment. That is the root source of declining skills and it is reasonable that firms may be less likely to hire disabled workers in a recession. Add in the lack of mobility that we have added with the housing crash and this is not at all mysterious why people might have trouble breaking back into the work force once they are delayed.

As for reduced mortality, sometimes that goes the other direction. Saving a person from a heart attack (who would previously have died) may result in a person with lower cardiac function and with less endurance than before. In a full employment scenario they can fight to stay in the workforce because there is a shortage of good people. But in a massive recession they can no longer compete and disability is actually a correct description of why they cannot compete.

It's an economist way to think about things, that someone being in the labor force means they're choosing the "work option." But in recession the options for some are no work and no money (otherwise known as "homelessness") or managing to qualify for disability (average monthly payment about $1100, max benefit about $2500). If you have some form of disability, you might be able to work if you have a job and employer that can accommodate you, but lose that job and you're probably going to be out of luck.

This isn't really mysterious stuff. Someone is 61, has a moderate disability, and loses his/her job. There is no work option.This was in response to an article by Edward Glaeser puzzling over why the social security disability roles are suddenly rising, including such gems as

Ultimately, the best recipe for fighting poverty is investment in human capital. This starts with improving our education system, an undertaking that should include experiments with digital learning, incentives for attracting good teachers and retooling community colleges so they provide marketable skills to less-advantaged Americans.

and

The steady rise in disability claims presents something of a puzzle. Medicine has improved substantially. Far fewer of us labor in dangerous industrial jobs like the ones that originally motivated disability insurance. The rate of deaths due to injuries has plummeted. Behavior that can cause disability, such as alcohol use and smoking, has declined substantially. American age-adjusted mortality rates are far lower than in the past.Has Professor Glaeser noted tuition costs lately? Or looked at the consequences of defaulting on student loans? The opportunity cost for a semi-disabled worker to go back to school, go wildly into debt and then risk having social security garnished to pay wages is very high.

The real issue is unemployment. That is the root source of declining skills and it is reasonable that firms may be less likely to hire disabled workers in a recession. Add in the lack of mobility that we have added with the housing crash and this is not at all mysterious why people might have trouble breaking back into the work force once they are delayed.

As for reduced mortality, sometimes that goes the other direction. Saving a person from a heart attack (who would previously have died) may result in a person with lower cardiac function and with less endurance than before. In a full employment scenario they can fight to stay in the workforce because there is a shortage of good people. But in a massive recession they can no longer compete and disability is actually a correct description of why they cannot compete.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

I'll be talking about the future in the future

A poverty comment

There were wo articles that led to me agreeing with Matt Yglesias about refocusing on cash transfers and wporrying less about how the money is spent. One, was an expose on how the state of Georgia tries to keep people from receiving benefits. Now it is fair pool to decide that, as a state or a society, that you don't want to give these benefits. But doesn't it make sense to make that decision transparently instead of slowing adding in extra steps?

The other one was a link I found on Felix Salmon's webste called "Stop subsizing obesity". What made this article surreal was that we did not get a discussion of ways to change agricultural subsidies to make high fructose corn syrup a less prevalent addition. No, what we go was an attack on food stamps:

So these types of issues are what are making me think maybe we should be much more basic in our approach to charity.

The other one was a link I found on Felix Salmon's webste called "Stop subsizing obesity". What made this article surreal was that we did not get a discussion of ways to change agricultural subsidies to make high fructose corn syrup a less prevalent addition. No, what we go was an attack on food stamps:

This could happen in two ways: first, remove the subsidy for sugar-sweetened beverages, since no one without a share in the profits can argue that the substance plays a constructive role in any diet. “There’s no rationale for continuing to subsidize them through SNAP benefits,” says Ludwig, “with the level of science we have linking their consumption to obesity, diabetes and heart disease.” New York City proposed a pilot program that would do precisely this back in 2011; it was rejected by the Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “too complex.”Now, of all the targets they could go after, soda is the one that I am the most sympathetic to. I have bene trying (with mixed success) to radically reduce my own consumption of the substance. But look at the sorts of ideas that come out next:

Simultaneously, make it easier to buy real food; several cities, including New York, have programs that double the value of food stamps when used for purchases at farmers markets. The next step is to similarly increase the spending power of food stamps when they’re used to buy fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains, not just in farmers markets but in supermarkets – indeed, everywhere people buy food.Can we say the word "arbitrage opportunity"? Maybe it would be inefficient, but look at how much more complex you are making a very basic program in order to reach a social goal. And why are we targeting it at food stamp recipients? If this is a worthwhile way to combat obesity, why not use a vice tax (which is an approach I can at least conceptually support).

So these types of issues are what are making me think maybe we should be much more basic in our approach to charity.

The difficulties in talking about TV viewership.

In response to this post on television's surprising longevity, Andrew Gelman pointed out that ratings really have plummeted:

1. 52 weeks a year

It took years for the networks to catch on to the potential of the rerun. You'll see this credited to the practice of broadcasting live, but the timelines don't match up. Long seasons continued until well into the Sixties and summer replacement shows into the Seventies. With the advent of reruns, the big three networks started selling the same shows twice whereas before the viewers for the first time an episode aired was often all the viewers it would ever have. Should we be talking about the number of people who watched a particular airing or should we consider the total number of people who saw an episode over all its airings?

2. The big three... four... five... five and a half...

Speaking of the big three, when we talk about declining ratings, we need to take into account that the network pie is now sliced more ways with the addition of Fox, CW, Ion, MyNetwork and possibly one or two I'm forgetting.

3. But if you had cable you could be watching NCIS and the Big Bang Theory

A great deal of cable programming is recycled network programming. If we count viewership as the total number of times a program is viewed (a defensible if not ideal metric), you could actually argue that the number is trending up for shows produced for and originally shown on the networks.

4. When Netflix is actually working...

Much has been made of on-line providers as a threat to the networks, but much of their business model current relies streaming old network shows. This adds to our total views tally. (Attempts at moving away from this recycling model are, at best, preceding slowly.)

5. I'm waiting for the Blu-ray

Finally, the viewership and revenue from network shows has been significantly enhanced by DVDs and Blu-rays

I don't want to make too much of this. Network television does face real challenges, cable has become a major source of programming (including personal favorites like Justified, Burn Notice and the Closer), and web series are starting to show considerable promise. The standard twilight-of-the-networks narrative may turn out to be right this time. I'm just saying that, given resilience if the institutions and the complexities of thinking about non-rival goods, I'd be careful about embracing any narrative too quickly.

[T]he other day I happened to notice a feature in the newspaper giving the ratings of the top TV shows, and . . . I was stunned (although, in retrospect, maybe I shouldn't've been) by how low they were. Back when I was a kid there was a column in the newspaper giving the TV ratings every week, and I remember lots of prime-time shows getting ratings in the 20's. Nowadays a top show can have a rating of less than 5.Undoubtedly, there has been a big drop here (as you would expect given that broadcast television used to have an effective monopoly over home entertainment), but has the drop been as big as it looks? There are a few mitigating factors, particularly if we think about total viewership for each episode (or even each minute) of a show and the economics of non-rival goods:

1. 52 weeks a year

It took years for the networks to catch on to the potential of the rerun. You'll see this credited to the practice of broadcasting live, but the timelines don't match up. Long seasons continued until well into the Sixties and summer replacement shows into the Seventies. With the advent of reruns, the big three networks started selling the same shows twice whereas before the viewers for the first time an episode aired was often all the viewers it would ever have. Should we be talking about the number of people who watched a particular airing or should we consider the total number of people who saw an episode over all its airings?

2. The big three... four... five... five and a half...

Speaking of the big three, when we talk about declining ratings, we need to take into account that the network pie is now sliced more ways with the addition of Fox, CW, Ion, MyNetwork and possibly one or two I'm forgetting.

3. But if you had cable you could be watching NCIS and the Big Bang Theory

A great deal of cable programming is recycled network programming. If we count viewership as the total number of times a program is viewed (a defensible if not ideal metric), you could actually argue that the number is trending up for shows produced for and originally shown on the networks.

4. When Netflix is actually working...

Much has been made of on-line providers as a threat to the networks, but much of their business model current relies streaming old network shows. This adds to our total views tally. (Attempts at moving away from this recycling model are, at best, preceding slowly.)

5. I'm waiting for the Blu-ray

Finally, the viewership and revenue from network shows has been significantly enhanced by DVDs and Blu-rays

I don't want to make too much of this. Network television does face real challenges, cable has become a major source of programming (including personal favorites like Justified, Burn Notice and the Closer), and web series are starting to show considerable promise. The standard twilight-of-the-networks narrative may turn out to be right this time. I'm just saying that, given resilience if the institutions and the complexities of thinking about non-rival goods, I'd be careful about embracing any narrative too quickly.

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

The difference between fantasy and reality

There are no real surprises in this ABC News story (via Digby), nothing that common sense couldn't tell you, but given recent statements by the NRA and its allies, this is an excellent reminder of the huge gap between the action-hero fantasy and the reality of these situations.

Police officers and military personnel are selected for having suitable skills and personality, trained extensively and continuously and re-evaluated on a regular basis and yet even they avoid these scenarios whenever possible (and occasionally end up shooting themselves or innocent bystanders when the situations are unavoidable)..

While there are exceptions, the odds of a civilian with a concealed weapon actually helping are extraordinarily small.

Most of us fantasize about being able to do what an Army Ranger or a SWAT team member can do. There's nothing wrong with fantasizing or even with acting out those fantasies with cardboard targets on a shooting range.

The trouble is, as our gun culture has grown more fantasy based, the people like Wayne LaPierre have increasingly lost the ability to distinguish between real life and something they saw in a movie.

Police officers and military personnel are selected for having suitable skills and personality, trained extensively and continuously and re-evaluated on a regular basis and yet even they avoid these scenarios whenever possible (and occasionally end up shooting themselves or innocent bystanders when the situations are unavoidable)..

While there are exceptions, the odds of a civilian with a concealed weapon actually helping are extraordinarily small.

Most of us fantasize about being able to do what an Army Ranger or a SWAT team member can do. There's nothing wrong with fantasizing or even with acting out those fantasies with cardboard targets on a shooting range.

The trouble is, as our gun culture has grown more fantasy based, the people like Wayne LaPierre have increasingly lost the ability to distinguish between real life and something they saw in a movie.

Boxing Day Brain Teasers

Here are a couple to ponder. I've got answers (as well as the inevitable pedagogical discussions) over at You Do the Math.

1. If a perfect square isn't divisible by three, then it's always one more than a multiple off three, never one less. Can you see why?

2. Given the following

A B D _______________________________________________

C E F G

Where does the 'H' go?

1. If a perfect square isn't divisible by three, then it's always one more than a multiple off three, never one less. Can you see why?

2. Given the following

A B D _______________________________________________

C E F G

Where does the 'H' go?

Charity

I am quite in agreement with this sentiment:

Neither of these seems to be on the table at the moment.

Obviously there's a risk that some of the money will be "wasted" on booze or tobacco but in practice that looks like much less wastage than the guaranteed waste involved in a high-overhead prescriptive charity.It seems that the cost of "targeting charity" are actually quite high. In general, we don't like to prescribe how people spend money from other sources. I am not sure that it really makes sense to do so in the case of poverty, either, given the surprisingly large costs required to ensure that the aid is spent precisely the way that the giver intended. Now, it is true that earned income would be even better but the only way for a government to accomplish that would be with either monetary policy or a jobs program.

Neither of these seems to be on the table at the moment.

Tuesday, December 25, 2012

Sunday, December 23, 2012

As American as Wyatt Earp

As I mentioned before, today's gun culture is radically different from the one I grew up with. On a related note, the gun rights movement, while often presented as conservative (pushing back against liberal advances) or reactionary (wanting to return to the standards of the past), is actually radical (advocating a move to a state that never existed). The idea that people have an absolute right to carry a weapon anywhere, at any time and in any fashion was never the norm, not even in the period that forms the basis for so much of the personal mythology of the gun rights movement.

UCLA professor of law, Adam Winkler

UCLA professor of law, Adam Winkler

Guns were obviously widespread on the frontier. Out in the untamed wilderness, you needed a gun to be safe from bandits, natives, and wildlife. In the cities and towns of the West, however, the law often prohibited people from toting their guns around. A visitor arriving in Wichita, Kansas in 1873, the heart of the Wild West era, would have seen signs declaring, "Leave Your Revolvers At Police Headquarters, and Get a Check."These facts aren't contested. They aren't obscure. You can even find them in classic Westerns like Winchester '73.

A check? That's right. When you entered a frontier town, you were legally required to leave your guns at the stables on the outskirts of town or drop them off with the sheriff, who would give you a token in exchange. You checked your guns then like you'd check your overcoat today at a Boston restaurant in winter. Visitors were welcome, but their guns were not.

In my new book, Gunfight: The Battle over the Right to Bear Arms in America, there's a photograph taken in Dodge City in 1879. Everything looks exactly as you'd imagine: wide, dusty road; clapboard and brick buildings; horse ties in front of the saloon. Yet right in the middle of the street is something you'd never expect. There's a huge wooden billboard announcing, "The Carrying of Firearms Strictly Prohibited."

While people were allowed to have guns at home for self-protection, frontier towns usually barred anyone but law enforcement from carrying guns in public.

When Dodge City residents organized their municipal government, do you know what the very first law they passed was? A gun control law. They declared that "any person or persons found carrying concealed weapons in the city of Dodge or violating the laws of the State shall be dealt with according to law." Many frontier towns, including Tombstone, Arizona--the site of the infamous "Shootout at the OK Corral"--also barred the carrying of guns openly.

Today in Tombstone, you don't even need a permit to carry around a firearm. Gun rights advocates are pushing lawmakers in state after state to do away with nearly all limits on the ability of people to have guns in public.

Like any law regulating things that are small and easy to conceal, the gun control of the Wild West wasn't always perfectly enforced. But statistics show that, next to drunk and disorderly conduct, the most common cause of arrest was illegally carrying a firearm. Sheriffs and marshals took gun control seriously.

In 1876, Lin McAdam (James Stewart) and friend 'High-Spade' Frankie Wilson (Millard Mitchell) pursue outlaw 'Dutch Henry' Brown (Stephen McNally) into Dodge City, Kansas. They arrive just in time to see a man forcing a saloon-hall girl named Lola (Shelley Winters) onto the stage leaving town. Once the man reveals himself to be Sheriff Wyatt Earp (Will Geer) Lin backs down. Earp informs the two men that firearms are not allowed in town and they must check them in with Earp's brother Virgil.In other words, even people who learned their history from old movies should know there's something extreme going on.

Traditional vs. current gun culture

Both Joseph and I come from parts of the world (Northern Ontario and the lower Ozarks, respectively) where guns played a large part in the culture. Hunting and fishing was big. This was mainly for sport, though there were families that significantly supplemented their diet with game and most of the rest of us had family members who remembered living off the land.

We also have a different take on guns for defense. When a call to the police won't bring help within forty-five minutes (often more than that where Joseph grew up), a shotgun under the bed starts sounding much more sensible.

Guns have never been a big part of my life, but I'm comfortable with them. I know what it's like to use a rifle, a shotgun and a revolver. I don't get any special emotional thrill from firing a gun but I do appreciate the satisfaction of knocking a can off of a post.

I think this perspective is important in the debate for a couple of reasons: first, because many discussions on the left often get conflated with impressions and prejudices about rural America and the South and second, (and I think this is the bigger issue) because these traditional ideas are becoming increasingly marginalized in the gun rights movement.

Gun culture has changed radically since the Eighties, as this TPM reader explains

But when we talk about "tactical" weapons, we're no longer talking reasonable scenarios for civilians. Regular people don't need thirty round magazines and laser sights to defend themselves. They need these things to live out fantasies, scenes they saw in movies. We're talking about different guns with an entirely different culture.

We also have a different take on guns for defense. When a call to the police won't bring help within forty-five minutes (often more than that where Joseph grew up), a shotgun under the bed starts sounding much more sensible.

Guns have never been a big part of my life, but I'm comfortable with them. I know what it's like to use a rifle, a shotgun and a revolver. I don't get any special emotional thrill from firing a gun but I do appreciate the satisfaction of knocking a can off of a post.

I think this perspective is important in the debate for a couple of reasons: first, because many discussions on the left often get conflated with impressions and prejudices about rural America and the South and second, (and I think this is the bigger issue) because these traditional ideas are becoming increasingly marginalized in the gun rights movement.

Gun culture has changed radically since the Eighties, as this TPM reader explains

Most of the men and children (of both sexes) I met were interested in hunting, too. Almost exclusively, they used traditional hunting rifles: bolt-actions, mostly, but also a smattering of pump-action, lever-action, and (thanks primarily to Browning) semi-automatic hunting rifles. They talked about gun ownership primarily as a function of hunting; the idea of “self-defense,” while always an operative concern, never seemed to be of paramount importance. It was a factor in gun ownership - and for some sizeable minority of gun owners, it was of outsized (or of decisive) importance - but it wasn’t the factor. The folks I interacted with as a pre-adolescent and - less so - as a teen owned guns because their fathers had owned guns before them; because they’d grown up hunting and shooting; and because - for most of them - it was an experience (and a connection) that they wanted to pass on to their sons and daughters.There's one distinction I want to add here. There are reasonable scenarios where a pump action shotgun or a reliable revolver might get a rural homeowner, a clerk at a convenience store or a business traveler who can't always avoid risky itineraries out of trouble.

And that’s my point: I can’t remember seeing a semi-automatic weapon of any kind at a shooting range until the mid-1980’s. Even through the early-1990’s, I don’t remember the idea of “personal defense” being a decisive factor in gun ownership. The reverse is true today: I have college-educated friends - all of whom, interestingly, came to guns in their adult lives - for whom gun ownership is unquestionably (and irreducibly) an issue of personal defense. For whom the semi-automatic rifle or pistol - with its matte-black finish, laser site, flashlight mount, and other “tactical” accoutrements - effectively circumscribe what’s meant by the word “gun.” At least one of these friends has what some folks - e.g., my fiancee, along with most of my non-gun-owning friends - might regard as an obsessive fixation on guns; a kind of paraphilia that (in its appetite for all things tactical) seems not a little bit creepy. Not “creepy” in the sense that he’s a ticking time bomb; “creepy” in the sense of…alternate reality. Let’s call it “tactical reality.”

The “tactical” turn is what I want to flag here. It has what I take to be a very specific use-case, but it’s used - liberally - by gun owners outside of the military, outside of law enforcement, outside (if you’ll indulge me) of any conceivable reality-based community: these folks talk in terms of “tactical” weapons, “tactical” scenarios, “tactical applications,” and so on. It’s the lingua franca of gun shops, gun ranges, gun forums, and gun-oriented Youtube videos. (My god, you should see what’s out there on You Tube!) Which begs my question: in precisely which “tactical” scenarios do all of these lunatics imagine that they’re going to use their matte-black, suppressor-fitted, flashlight-ready tactical weapons? They tend to speak of the “tactical” as if it were a fait accompli; as a kind of apodeictic fact: as something that everyone - their customers, interlocutors, fellow forum members, or YouTube viewers - experiences on a regular basis, in everyday life. They tend to speak of the tactical as reality.

But when we talk about "tactical" weapons, we're no longer talking reasonable scenarios for civilians. Regular people don't need thirty round magazines and laser sights to defend themselves. They need these things to live out fantasies, scenes they saw in movies. We're talking about different guns with an entirely different culture.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

The end was near a long time ago

While working on an upcoming post, I came across this quote from a 1989 NYT profile of Fred Silverman:

Experts started predicting the death of the big three networks about forty years ago when VCRs and satellites starting changing the landscape. That means that people have been predicting the imminent demise of the networks for more than half the time TV networks have been around.

At some point, technology will kill off ABC, CBS or NBC, but they've already outlasted many predictions and a lot of investors who lost truckloads of money over the past forty years chasing the next big thing would have been better off sticking with a dying technology.

Ddulites make lousy investors.

He said going back to a network does not interest him. He added that he would tell any executive who took a network job to ''take a lot of chances and really go for it.''Given all we hear about how fast things are changing and those who don't embrace the future are doomed, it's healthy to step back and remind ourselves that, while there is certainly some truth to these claims, change often takes longer that people expect.

''This is not a point in time to be conservative,'' he said. ''The only way to stop the erosion in network television is to come up with shows that are very popular.''

Experts started predicting the death of the big three networks about forty years ago when VCRs and satellites starting changing the landscape. That means that people have been predicting the imminent demise of the networks for more than half the time TV networks have been around.

At some point, technology will kill off ABC, CBS or NBC, but they've already outlasted many predictions and a lot of investors who lost truckloads of money over the past forty years chasing the next big thing would have been better off sticking with a dying technology.

Ddulites make lousy investors.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)