Comments, observations and thoughts from two bloggers on applied statistics, higher education and epidemiology. Joseph is an associate professor. Mark is a professional statistician and former math teacher.

Monday, November 26, 2012

Profile of a businessman I admire

I was working on a longer post about what a well run business looks like and I remembered the following Malcolm Gladwell piece for the New Yorker. When you read the first paragraph, you'll think the title of this post is a joke; when you get to the end, you'll know it's not.

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Hostess and salaries

Mark pointed out that, in my Hostess and wages post, I only put in the previous wage cuts and not the new one that management was proposing. The relevant passage:

In some ways this links to a broader trend of firms being reluctant to actually pay workers. This is linked to a reluctance to train workers, as well, but that only makes sense. But here is where the whole story gets surreal to me. Employees are assets as well as expenses. We all seem to get that when we pay CEOs a lot of money -- we argue that it is not just an expense but also an investment in talent. It is true that the modern world of corporate America has been very good at breaking down trust (few employees an informal promise at all anymore).

That is part of the issue with Hostess. Not only were they trying to drop wages but the pattern of action on the part of the management team was to focus entirely on the easy target of salaries and ignore the hard targets of actually using information to reform the company into a more competitive shape. Now maybe that was impossible (it seems unlikely but who knows). But then we'd expect all of the bakers to be going under.

Nor is it impossible for firms to make highly creative moves to try and survive. Notice how McDonald's and Starbucks (two companies that I consider well run) have quietly tried to sneak into each other's space. Suddenly there is an egg sandwich at Starbucks (why go to two drive-thrus in the morning?). And there are Latte's at McDonalds (why pay $5 for a Latte if you can't tell the difference). Both firms are tougher, as a result, and -- as a pleasant side effect -- customers are better off.

But I want to go back to Mark's piece -- if you want to give management credit for a well run business strategy then you should be suspicious when failure is entirely blamed on the employees (who, t the union level, typically do not craft strategy).

Again, the 14-year Hostess bakery veteran: “Remember how I said I made $48,000 in 2005 and $34,000 last year? I would make $25,000 in five years if I took their offer. It will be hard to replace the job I had, but it will be easy to replace the job they were trying to give me.”One thing that is easy to overlook in the discussion of did Unions show inflexibility is that a 50% wage cut over less than 10 years is an amazing drop in nominal wage (and the initial drop from 30,000 to 19,000 employees). Mark's piece has pointed out that management was not doing any of the obvious moves to try save the business. While the actual pattern of executive compensation is slightly more complicated than early reports indicated, it is pretty clear that huge (long term) wage cuts were not envisioned in the executive suite.

In some ways this links to a broader trend of firms being reluctant to actually pay workers. This is linked to a reluctance to train workers, as well, but that only makes sense. But here is where the whole story gets surreal to me. Employees are assets as well as expenses. We all seem to get that when we pay CEOs a lot of money -- we argue that it is not just an expense but also an investment in talent. It is true that the modern world of corporate America has been very good at breaking down trust (few employees an informal promise at all anymore).

That is part of the issue with Hostess. Not only were they trying to drop wages but the pattern of action on the part of the management team was to focus entirely on the easy target of salaries and ignore the hard targets of actually using information to reform the company into a more competitive shape. Now maybe that was impossible (it seems unlikely but who knows). But then we'd expect all of the bakers to be going under.

Nor is it impossible for firms to make highly creative moves to try and survive. Notice how McDonald's and Starbucks (two companies that I consider well run) have quietly tried to sneak into each other's space. Suddenly there is an egg sandwich at Starbucks (why go to two drive-thrus in the morning?). And there are Latte's at McDonalds (why pay $5 for a Latte if you can't tell the difference). Both firms are tougher, as a result, and -- as a pleasant side effect -- customers are better off.

But I want to go back to Mark's piece -- if you want to give management credit for a well run business strategy then you should be suspicious when failure is entirely blamed on the employees (who, t the union level, typically do not craft strategy).

For those of you who are still working their way through the leftovers

Thanksgiving, 1905 from the incomparable Windsor McCay

from Mippyville.

update: the hash was very good, thanks for asking

Saturday, November 24, 2012

The real reason for almost all big business failures

The commonly voiced view of business, red in tooth and claw, a Darwinian landscape where only the fit survive may hold for small to mid-sized operations, but with big business, survival is surprisingly easy. As a rule it is only the remarkably unfit that die. When you see a big company go under you can generally find a history of incompetent management and stupid or shortsighted decisions.

Though as narrative-obsessed as their political brethren, business journalists tend to be notably averse to stories built around the question "what happens when you give the keys to an idiot?" That's a shame because some of the most entertaining accounts start with that premise. It's understandable though. Business journalists, once again like their political brethren, tend to have overly cozy relationships with their subjects and, (compared to reporters thirty or forty) tend to sympathize more with management than labor.

The decline of professional standards also plays a part. A surprising number of "news" stories are actually press releases in only slightly rewritten form and PR department go to great lengths to avoid statements that make their bosses look like morons.

Given these factors and the uncomfortable cognitive dissonance that journalists often feel when forced to report that a major corporation's management is incompetent, they will almost always pass over the obvious narrative and opt instead for one of these three standards:

1. the company was made obsolete by new technology;

2. it was doomed by changing markets;

3. it just couldn't get good help.

Of course, in theory, these things can doom a company, in practice though, when you hear one of these explanations given for a collapse, you will almost always find that managerial malpractice played at least as large a role. For example, ebooks had much less to do with Borders demise than did an ill-conceived expansion into the ridiculously over-served British market.*

Here the LA Times invaluable Michael Hiltzik takes apart the standard narratives (numbers 2 and 3) of the troubles at Hostess (via Thoma, as usual)

UPDATE * I meant to include a link to this growth fetish post that gives my take on what the people at Borders might have been thinking.

Though as narrative-obsessed as their political brethren, business journalists tend to be notably averse to stories built around the question "what happens when you give the keys to an idiot?" That's a shame because some of the most entertaining accounts start with that premise. It's understandable though. Business journalists, once again like their political brethren, tend to have overly cozy relationships with their subjects and, (compared to reporters thirty or forty) tend to sympathize more with management than labor.

The decline of professional standards also plays a part. A surprising number of "news" stories are actually press releases in only slightly rewritten form and PR department go to great lengths to avoid statements that make their bosses look like morons.

Given these factors and the uncomfortable cognitive dissonance that journalists often feel when forced to report that a major corporation's management is incompetent, they will almost always pass over the obvious narrative and opt instead for one of these three standards:

1. the company was made obsolete by new technology;

2. it was doomed by changing markets;

3. it just couldn't get good help.

Of course, in theory, these things can doom a company, in practice though, when you hear one of these explanations given for a collapse, you will almost always find that managerial malpractice played at least as large a role. For example, ebooks had much less to do with Borders demise than did an ill-conceived expansion into the ridiculously over-served British market.*

Here the LA Times invaluable Michael Hiltzik takes apart the standard narratives (numbers 2 and 3) of the troubles at Hostess (via Thoma, as usual)

Let's get a few things clear. Hostess didn't fail for any of the reasons you've been fed. It didn't fail because Americans demanded more healthful food than its Twinkies and Ho-Hos snack cakes. It didn't fail because its unions wanted it to die.

It failed because the people that ran it had no idea what they were doing. Every other excuse is just an attempt by the guilty to blame someone else.

...

Hostess management's efforts to blame union intransigence for the company's collapse persisted right through to the Thanksgiving eve press release announcing Hostess' liquidation, when it cited a nationwide strike by bakery workers that "crippled its operations."

That overlooks the years of union givebacks and management bad faith. Example: Just before declaring bankruptcy for the second time in eight years Jan. 11, Hostess trebled the compensation of then-Chief Executive Brian Driscoll and raised other executives' pay up to twofold. At the same time, the company was demanding lower wages from workers and stiffing employee pension funds of $8 million a month in payment obligations.

Hostess management hasn't been able entirely to erase the paper trail pointing to its own derelictions. Consider a 163-page affidavit filed as part of the second bankruptcy petition.

There Driscoll outlined a "Turnaround Plan" to get the firm back on its feet. The steps included closing outmoded plants and improving the efficiency of those that remain; upgrading the company's "aging vehicle fleet" and merging its distribution warehouses for efficiency; installing software at the warehouses to allow it to track inventory; and closing unprofitable retail stores. It also proposed to restore its advertising budget and establish an R&D program to develop new products to "maintain existing customers and attract new ones."

None of these steps, Driscoll attested, required consultation with the unions. That raises the following question: You mean to tell me that as of January 2012, Hostess still hadn't gotten around to any of this?

The company had known for a decade or more that its market was changing, but had done nothing to modernize its product line or distribution system. Its trucks were breaking down. It was keeping unprofitable stores open and having trouble figuring out how to move inventory to customers and when. It had cut back advertising and marketing to the point where it was barely communicating with customers. It had gotten hundreds of millions of dollars in concessions from its unions, and spent none of it on these essential improvements.

The true recent history of Hostess can be excavated from piles of public filings from its two bankruptcy cases. To start with, the company has had six CEOs in the last 10 years, which is not exactly a precondition for consistent and effective corporate strategizing.

...

Hostess first entered bankruptcy in 2004, when it was known as Interstate Bakeries. During its five years in Chapter 11, the firm obtained concessions from its unions worth $110 million a year. The unions accepted layoffs that brought the workforce down to about 19,000 from more than 30,000. There were cuts in wages, pension and health benefits. The Teamsters committed to negotiations over changes in antiquated work rules. The givebacks helped reduce Hostess' labor costs to the point where they were roughly equal to or even lower than some of its major competitors'.

But the firm emerged from bankruptcy with more debt than when it went in — in with $575 million, out with $774 million, all secured by company assets. That's pretty much the opposite of what's supposed to happen in bankruptcy. By the end, there was barely a spare distributor cap in the motor pool that wasn't mortgaged to the private equity firms and hedge funds holding the notes (and also appointing management).

...

The post-bankruptcy leadership never executed a growth strategy. It failed to introduce a significant new product or acquire a single new brand. It lagged on bakery automation and product R&D, while rivals such as Bimbo Bakeries USA built research facilities and hired food scientists to keep their product lines fresh. At the time of the 2004 bankruptcy, Hostess was three times the size of Bimbo. Today it's less than half Bimbo's size. (Bimbo, which has been acquiring bakeries such as Sara Lee and Entenmann's right and left, might well end up with Hostess' brands.)

UPDATE * I meant to include a link to this growth fetish post that gives my take on what the people at Borders might have been thinking.

"Lance Armstrong And The Business Of Doping"

This Planet Money story is the first (and will probably be the last) account of the Armstrong scandal that has held my interest. It also changed my what's-the-big-deal attitude.

To have one $8 billion dollar writedown, Ms. Whitman, may be regarded as a misfortune. To have two looks like carelessness.

Ryan McCarthy in Counterparties:

HP has become the place where synergies go to die. In its earnings release today, HP said it has taken an $8.8 billion writedown, caused by what it calls “serious accounting improprieties” at Autonomy, a software company it acquired for $11 billion in August 2011. This, as David Benoit notes, is HP’s second acquisition-related $8 billion writedown of the year.I love the phrase "flexible definition."

HP is furiously pointing fingers: in a statement, the company said there was a “willful effort on behalf of certain former Autonomy employees to inflate the underlying financial metrics”. And CEO Meg Whitman told analysts that Deloitte had signed off on Autonomy’s accounts, with KPMG signing off on Deloitte. Still, only $5 billion of this quarter’s write down came from Autonomy’s accounting; the rest came from those pesky “headwinds against anticipated synergies and marketplace performance”.

There’s a strong case that HP should have smelled a rat. Bryce Elder points to “a decade’s worth of research questioning Autonomy’s revenue recognition, organic growth and seemingly flexible definition of a contract sale”. Then there’s the scathing statement which came about a month after the HP sale, in which Oracle revealed that it too had looked at Autonomy, but considered the company’s $6 billion market value to be “extremely over-priced”. Lynch, for his part, says that he was “ambushed” by the allegations.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Introducing "You Do the Math"

As Joseph mentioned earlier, I have a new blog up called You Do the Math focusing on ideas for teaching primary and secondary math. There's going to be a fair amount of cross-posting with this blog but I wanted a second outlet because:

1. I have a decade's worth of tips, exercises, lesson plans, test ideas, games, and puzzles for math teachers, much of which wouldn't be of much interest to most of the readers of this site.

2. I couldn't see the typical fifth grade teacher slogging through posts on the economics of health care and the potential for selection effects in polling and the rest of the analytic esoterica you'll find here.

3. I had some ideas I wanted to play around with. Since so many of the teaching posts aren't time sensitive, I'm using the scheduling function to keep a steady stream of content flowing. Many of the posts will be short and or recycled but I've already scheduled at least one a week for the next five months. When I get to six months I plan to go back to the beginning and start putting up a second post for each week. It will be interesting to so what the effect is on traffic, page rank, etc.

4. Pauline Kael talked about the way writing a regular column helped her discipline and organize her thinking about movies. I believe a blog can serve much the same function in other areas.

I've already got one up that talks about using codes to introduce numberlines and tables and another that shows how you can estimate pi by seeing how many times randomly selected points fall within a given radius and I have about two dozen more posts sitting in the queue. If this sort of thing sounds interesting to you, check it out and if you know of anyone who might have use for this, please pass it on.

Thanks,

Mark

1. I have a decade's worth of tips, exercises, lesson plans, test ideas, games, and puzzles for math teachers, much of which wouldn't be of much interest to most of the readers of this site.

2. I couldn't see the typical fifth grade teacher slogging through posts on the economics of health care and the potential for selection effects in polling and the rest of the analytic esoterica you'll find here.

3. I had some ideas I wanted to play around with. Since so many of the teaching posts aren't time sensitive, I'm using the scheduling function to keep a steady stream of content flowing. Many of the posts will be short and or recycled but I've already scheduled at least one a week for the next five months. When I get to six months I plan to go back to the beginning and start putting up a second post for each week. It will be interesting to so what the effect is on traffic, page rank, etc.

4. Pauline Kael talked about the way writing a regular column helped her discipline and organize her thinking about movies. I believe a blog can serve much the same function in other areas.

I've already got one up that talks about using codes to introduce numberlines and tables and another that shows how you can estimate pi by seeing how many times randomly selected points fall within a given radius and I have about two dozen more posts sitting in the queue. If this sort of thing sounds interesting to you, check it out and if you know of anyone who might have use for this, please pass it on.

Thanks,

Mark

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Blog list updated

The blog roll has had a fall cleaning. I removed a few blogs that were really interesting but which had not been updated for months or years. I added two new blogs: Mark Palko's new math teaching blog (which may occasionally cross post) and Mark Thoma's Economist's View (for which it is past time we added it).

Happy Thanksgiving, all!

Toys for Tots -- reprinted, slightly revised

A good Christmas can do a lot to take the edge off of a bad year both for children and their parents (and a lot of families are having a bad year). It's the season to pick up a few toys, drop them by the fire station and make some people feel good about themselves during what can be one of the toughest times of the year.

If you're new to the Toys-for-Tots concept, here are the rules I normally use when shopping:

The gifts should be nice enough to sit alone under a tree. The child who gets nothing else should still feel that he or she had a special Christmas. A large stuffed animal, a big metal truck, a large can of Legos with enough pieces to keep up with an active imagination. You can get any of these for around twenty or thirty bucks at Wal-Mart or Costco;*

Shop smart. The better the deals the more toys can go in your cart;

No batteries. (I'm a strong believer in kid power);**

Speaking of kid power, it's impossible to be sedentary while playing with a basketball;

No toys that need lots of accessories;

For games, you're generally better off going with a classic;

No movie or TV show tie-ins. (This one's kind of a personal quirk and I will make some exceptions like Sesame Street);

Look for something durable. These will have to last;

For smaller children, you really can't beat Fisher Price and PlaySkool. Both companies have mastered the art of coming up with cleverly designed toys that children love and that will stand up to generations of energetic and creative play.

*I previously used Target here, but their selection has been dropping over the past few years and it's gotten more difficult to find toys that meet my criteria.

** I'd like to soften this position just bit. It's okay for a toy to use batteries, just not to need them. Fisher Price and PlaySkool have both gotten into the habit of adding lights and sounds to classic toys, but when the batteries die, the toys live on, still powered by the energy of children at play.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Bitter Harvest

Just in time for Thanksgiving.

From Marketplace:

From Marketplace:

Michael Hogan, CEO of A.D. Makepeace, a large cranberry grower based in Wareham, says for now cranberries are still a viable crop in Massachusetts. But climate change is making it much tougher to grow there.I know we've been over this before, but it gets harder and harder to see how a cost/benefit analysis of climate change don't support immediate implementation of a carbon tax.or something similar.

"We're having warmer springs, we're having higher incidences of pests and fungus and we're having warmer falls when we need to have cooler nights," Hogan says.

Those changing conditions are costing growers like Makepeace money. The company has to use more water to irrigate in the hotter summers, and to cover the berries in spring and fall to protect them from frosts.

They're also spending more on fuel to run irrigation pumps, and have invested heavily in technology to monitor the bogs more closely. It's also meant more fungicides and fruit rot.

"Because of the percentage of rot that was delivered to Ocean Spray, they paid us $2 a barrel less," Hogan says. "We delivered 370,000 barrels last year. So you're talking about millions of dollars."

Cranberries also need a certain number of "chilling hours" to ensure that deep red color. Glen Reid, assistant manager of cranberry operations for A.D. Makepeace, says that's a problem as well.

"The berries actually need cold nights to color up," Reid says. "Last year we had a big problem with coloring up the berries. We had a lot more white berries."

Some growers in the Northeast have already moved some cranberry production to chillier climates, like eastern Canada. Ocean Spray has started growing cranberries on a new farm in the province of New Brunswick.

Makepeace's Hogan is even considering Chile, which apparently has a favorable climate for growing the North American berry.

Economics: a new definition?

Is it fair to quote the definition of economics from the blurb for a book? If so, consider this definition in the blurb for Emily Oster's new book:

None of this mean that Emily shouldn't write this book. My own read on the alcohol and pregnancy angle is that the current advice does seem to be based on an excess of caution. But it seems odd to argue that being an economist is the key piece here. Jumping fields is fine and can often lead to amazing insights, but maybe we should call this shifting of fields what it is rather than expanding the definition of economics to make it less meaningful?

When Oster was expecting her first child, she felt powerless to make the right decisions for her pregnancy. How doctors think and what patients need are two very different things. So Oster drew on her own experience and went in search of the real facts about pregnancy using an economist’s tools. Economics is not just a study of finance. It’s the science of determining value and making informed decisions. To make a good decision, you need to understand the information available to you and to know what it means to you as an individual.So, when applied to a medical topic (like pregnancy) how does this differ from evidence based medicine? Should I be calling myself an economist?

None of this mean that Emily shouldn't write this book. My own read on the alcohol and pregnancy angle is that the current advice does seem to be based on an excess of caution. But it seems odd to argue that being an economist is the key piece here. Jumping fields is fine and can often lead to amazing insights, but maybe we should call this shifting of fields what it is rather than expanding the definition of economics to make it less meaningful?

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

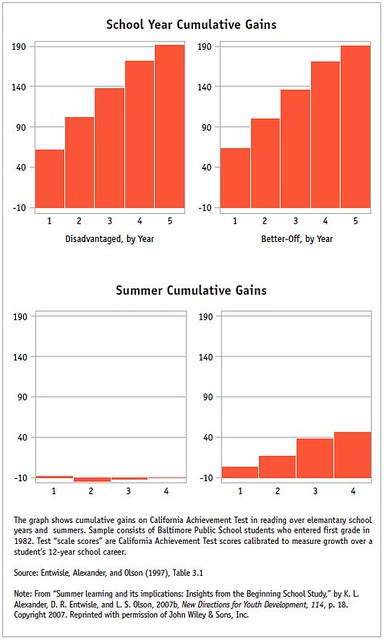

Depressing education chart of the day

Mike the Mad Biologist points us to this one.

From Karl Alexander (John Dewey Professor of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University):

UPDATE:

This seems like a good time to remind everyone about some of the other previously mentioned challenges these kids face:We discovered that about two-thirds of the ninth-grade academic achievement gap between disadvantaged youngsters and their more advantaged peers can be explained by what happens over the summer during the elementary school years.Mike goes on to point out the obvious question this raises about the fire-the-teachers approach to education reform.

I also want to point out that the higher performing group isn’t necessarily high income, but simply better off. In the context of the Baltimore City school system, that usually means solidly middle class, with parents who are likely to have gone to college versus dropping out.

Statistically, lower income children begin school with lower achievement scores, but during the school year, they progress at about the same rate as their peers. Over the summer, it’s a dramatically different story. During the summer months, disadvantaged children tread water at best or even fall behind. It’s what we call “summer slide” or “summer setback.” But better off children build their skills steadily over the summer months. The pattern was definite and dramatic. It was quite a revelation.

Hart and Risley also found that, in the first four years after birth, the average child from a professional family receives 560,000 more instances of encouraging feedback than discouraging feedback; a working- class child receives merely 100,000 more encouragements than discouragements; a welfare child receives 125,000 more discouragements than encouragements.

More on Hostess

There is a rumor that Mark is preparing a nice post on the whole Hostess bankruptcy story. So, to continue to generate context, consider this story from an actual employee:

Maybe the company was in an impossible situation. That is definitely one interpretation of the situation but the narrative is odd for this outcome. The argument that unions were to blame is hardly the case unless this account (above) is wracked with falsehoods. If the situation was hopeless then why did the high paid executives not call it over before raiding the pension? Was it because a longer tenure of salaries and job experience would be of personal benefit to them and they were no liable for the consequences of their decisions?

There are no easy answers, but a simple narrative of union greed or dysfunctional bargaining is clearly omitting lots of nuance. If nothing else, reneging on the repayment of the pension fund borrowing was hardly the ideal prelude to asking the union to trust future management promises.

In 2005 it was another contract year and this time there was no way out of concessions. The Union negotiated a deal that would save the company $150 million a year in labor. It was a tough internal battle to get people to vote for it. We turned it down twice. Finally the Union told us it was in our best interest and something had to give. So many of us, including myself, changed our votes and took the offer. Remember that next time you see CEO Rayburn on tv stating that we haven't sacrificed for this company. The company then emerged from bankruptcy. In 2005 before concessions I made $48,000, last year I made $34,000. My pay changed dramatically but at least I was still contributing to my self-funded pension.

In July of 2011 we received a letter from the company. It said that the $3+ per hour that we as a Union contribute to the pension was going to be 'borrowed' by the company until they could be profitable again. Then they would pay it all back. The Union was notified of this the same time and method as the individual members. No contact from the company to the Union on a national level.

This money will never be paid back. The company filed for bankruptcy and the judge ruled that the $3+ per hour was a debt the company couldn't repay. The Union continued to work despite this theft of our self-funded pension contributions for over a year. I consider this money stolen. No other word in the English language describes what they have done to this money.This illustrates a couple of things. One is that defined contribution pensions (i.e. the 401(k) and other such vehicles) are not necessarily a safe harbor from corporate games if something like this can happen without the union proactively agreeing. Two, the concessions made by the unions were pretty significant. They took pretty large pay cuts (29%) and lost additional money from the pension fund. No manager who made the decision to borrow this money was held liable.

Maybe the company was in an impossible situation. That is definitely one interpretation of the situation but the narrative is odd for this outcome. The argument that unions were to blame is hardly the case unless this account (above) is wracked with falsehoods. If the situation was hopeless then why did the high paid executives not call it over before raiding the pension? Was it because a longer tenure of salaries and job experience would be of personal benefit to them and they were no liable for the consequences of their decisions?

There are no easy answers, but a simple narrative of union greed or dysfunctional bargaining is clearly omitting lots of nuance. If nothing else, reneging on the repayment of the pension fund borrowing was hardly the ideal prelude to asking the union to trust future management promises.

Monday, November 19, 2012

Hoisted from the comments

A rather nice point from commenter Bill Trudo that I thought was worth emphasizing:

The problems at Hostess have been decades in the making. The company went into bankruptcy in 2004 and left in 2009 with numerous labor concessions, but without major reform to the pension system. Some people liked to blame that on the unions, but it is up to management to decide what is profitable or unprofitable. Now three years later, management has deemed their old agreements aren't profitable and that would be correct given how much money Hostess has been bleeding. And people still wonder why some union leaders were skeptical of management.

Skepticism is warranted, especially in light of Hostess having left bankruptcy in 2009 with more debt than it had in 2004 with falling sales. 2011 sales were down 28% from 2004. Of course, this is the union's fault that sales have dropped and not a failure of the company's leadership.

On top of that, management comes to the labor unions demanding 8% pay cuts and slashes to the pension, while the top executives increase their own pay--what a nice goodwill gesture. Some unsecured creditors actually filed suit over the pay raises.

Yes, pensions and work issues needed to be addressed. The unions had to make concessions, but it's difficult in light of what has happened for anyone to have any faith in what management has been doing at Hostess.

Now, enter two hedge funds, who hold the majority of secured debt, and they're likely looking to get out. After all, the business model isn't working; it's time for a showdown.

The Teamsters actually finally agreed to the wage and benefit concessions. Some of the other unions, including the Bakers' Union, didn't. Of course, I have a suspicion that some of the unions were acting in the best interest of all their union workers and not the union workers who were working at Hostess. Though, I also have suspicions that even if the unions capitulated to the hedge fund demands (they're the ones driving the show), Hostess would have likely been sold or have been back in bankruptcy in a few years.

This really gets to the core of the union/management dilemma -- it is hard to take things on faith. I remember many of my co-workers (including myself) putting in huge amounts of work for promises that never materialized. The classic "if you take a hit now we will remember you once this bad period is over". Curiously, it almost never works that way.

I also note that the narrative is "bad union wouldn't accept huge cuts" and not incompetent management was unable to make a top brand into a successful business. This is especially true of pension cuts. Underfunded pensions happen for a lot of reasons but they are usually much more of a management decision than a union decision. Maybe it was a bad decision for management to agree to the pension plan in the first place -- that is certainly possible. But it is always concerning to see no ethical qualms about removing obligations to workers (breaking agreements for work already done) while increasing your own wages.

What's with the (non)weird name?

Hi,

The regulars may have noticed something different about the top of the page. Observational Epidemiology is now West Coast Stat Views. This doesn't represent a change in content, rather a nod to truth in advertising. When this blog started, about two thousand posts ago, the name was both accurate and descriptive, but it soon morphed into a general statistics blog with a focus on topics that interested both of us and which connected (at least indirectly) with some relevant experience of one or both of us.

Both Joseph and I started out as corporate statisticians, so not surprisingly we're both mildly obsessed with business and economics. We both spent a great deal of time in academia so we're interested in education. As you'd expect from a blog originally called Observational Epidemiology, health care remains a big issue. As for politics and journalism, everybody needs a hobby.

Besides, I was getting tired of explaining what observational epidemiology meant.

Happy Holidays,

Mark

The regulars may have noticed something different about the top of the page. Observational Epidemiology is now West Coast Stat Views. This doesn't represent a change in content, rather a nod to truth in advertising. When this blog started, about two thousand posts ago, the name was both accurate and descriptive, but it soon morphed into a general statistics blog with a focus on topics that interested both of us and which connected (at least indirectly) with some relevant experience of one or both of us.

Both Joseph and I started out as corporate statisticians, so not surprisingly we're both mildly obsessed with business and economics. We both spent a great deal of time in academia so we're interested in education. As you'd expect from a blog originally called Observational Epidemiology, health care remains a big issue. As for politics and journalism, everybody needs a hobby.

Besides, I was getting tired of explaining what observational epidemiology meant.

Happy Holidays,

Mark

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)